The May Fair was held every year around at Great Brookfield (now part of Curzon Street and Shepherd Market) from 1–14 May. It had been established during the reign of Edward I, that king having granted a charter to the hospital of St. James’s to hold a fundraising fair “on the eve of St. James’, the day, and the morrow, and four days following,” being held originally in open fields beyond St. James, around Haymarket, – all to the north and west of St. James’s Hospital was open fields.

[NB: St James Hospital is the St James Infirmary, which gave its name to various versions of a popular folk, and later blues, song]

The fair was recorded as “Saint James’s fayer by Westminster” in 1560. Pepys speaks of it as St. James’s Fair. It was postponed in 1603 because of plague, but otherwise continued throughout the 17th century. In 1686, the fair moved to what is now Mayfair because of development and overcrowding around St James. Mayfair was mainly open fields until development began in the Shepherd Market area around 1686–88 to accommodate the Fair. Originally the Fair was conceived of mainly as a market for cattle and other livestock.

By the 18th century, it was one of the capital’s prime annual festivals, attracting showmen, jugglers and fencers and numerous fairground attractions. Popular attractions included bare-knuckle fighting, semolina eating contests (?) and women’s foot racing.

By the reign of George I, the May Fair had fallen into disrepute and was regarded as a public scandal. The 6th Earl of Coventry, who lived on Piccadilly, considered the fair to be a nuisance and, with local residents, led a public campaign against it. It was abolished in 1764. One reason for Mayfair’s subsequent boom in property development for wealthy homes was a concerted effort by these rich inhabitants to keep out the plebs.

The following notice of “the Fair in St. James’s” is quoted from Mackyn’s Diary by Mr. Frost, in his “Old Showmen of London,” as the earliest on record:—”The xxv. day of June [1560]. Saint James’s fayer by Westminster was so great that a man could not have a pygg for money; and the bear wiffes had nether meate nor drink before iiij. of cloke in the same day. And the chese went very well away for 1d. q. the pounde. Besides the great and mighti armie of beggares and bandes that were there.”

Beyond the fact that it was postponed for a few weeks or months in 1603, on account of the plague, nothing more is recorded concerning this fair till 1664, in which year, Mr. Frost tells us, “it was suppressed, as considered to tend rather to the advantage of looseness and irregularity, than to the substantial promotion of any good, common and beneficial to the people.”

If suppressed in 1664, it was back by the 1680s. By the reign of Queen Anne, the fair had a bad reputation. One writer complained:—”Oh! the piety of some people about the Queen, who can suffer things of this nature to go undiscovered to her Majesty, and consequently unpunished! Can any rational men imagine that her Majesty would permit so much lewdness as is committed at May Fair, for so many days together, so near to her royal palace, if she knew anything of the matter? I don’t believe the patent for that fair allows the patentees the liberty of setting up the devil’s shops and exposing his merchandise for sale.” Sadly not going into detail as to the precise nature, however, of this diabolic ware and “merchandise”.

According to Mr. Frost, “May Fair” did not assume any importance till about the year 1701, when the multiplication of shows of all kinds caused it to enlarge its sphere of attractions. “It was held,” he writes, “on the north side of Piccadilly, in Shepherd’s Market, Shepherd’s Court, White Horse Street, Sun Court, Market Court, and on the open space westwards, Chapel Street and Hertford Street, as far as Tyburn (now Park) Lane. The ground-floor of the Market House, usually occupied by butchers’ stalls, was appropriated during the fair to the sale of toys and gingerbread, and the upper portion was converted into a theatre. The open space westwards was covered with the booths of jugglers, fencers, and boxers, the stands of mountebanks, swings, roundabouts, &c.; while the sides of the streets were occupied by sausage-stalls and gambling-tables. The first-floor windows were also, in some instances, made to serve as the proscenia of puppet-shows.”

“I have been able to trace,” he adds, “only two shows to this fair in 1702, namely, Barnes and Finley’s, and Miller’s, which stood opposite to the former, and presented ‘an excellent droll called Crispin and Crispianus, or a shoe-maker a prince, with the best machines, singing, and dancing ever yet in the fair.’”

Pennant, who remembered the last “May Fair,” describes the locality as “covered with booths, temporary theatres, and every enticement to low pleasure.” A more minute description of the scene, evidently drawn from the life, is given by an antiquary named Carter, in the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1774.

“A mountebank’s stage,” this person tells us, “was erected opposite the ‘Three Jolly Butchers’ public-house, on the eastern side of the market area, now the ‘King’s Arms.’ Here Woodward, the inimitable comedian and harlequin, made his first appearance as ‘Merry Andrew;’ from these humble boards he soon after made his way to those of Covent Garden Theatre.”

The entertainments could verge on the bizarre. After the Scottish rebellion of 1745, a number of prominent rebels were beheaded. Chambers, in his “Book of Days,” writes that this sparked a May Fair entertainment: “the beheading of puppets formed one of the most regular and attractive parts of the exhibitions at the ‘May Fair,’ and was continued for several years.. Beheading of puppets took place in a coal-shed attached to a grocer’s shop (then Mr. Frith’s, now Mr. Frampton’s). One of these mock executions was exposed to the attending crowd. A shutter was fixed horizontally, on the edge of which, after many previous ceremonies, a puppet was made to lay its head, and another puppet instantly chopped it off with an axe. In a circular staircase-window, at the north end of Sun Court, a similar performance by another set of puppets took place. The 1745 execution of of the Scottish Jacobite chieftain, Lord Lovat, was repeatedly performed “in order to gratify the feelings of southern loyalty at the expense of that further north.”

The last great proprietor of such puppet-shows was a man named Flockton, whose puppets were in the height of their glory about 1790, and who retired soon after on a handsome competence. A puppet-show, under the name of the Marionettes, was revived at St. James’s Hall about the year 1872.

Another regular at these annual gatherings was “Tiddy Dol,” an eccentric gingerbread seller, who figures in Hogarth’s well-known picture of the “Idle Apprentice” at Tyburn, in his ornamental dress, in the crowd holding up a gingerbread cake in his hand and addressing the mob. Another attraction was a Frenchman, whose name has been forgotten, who exhibited his wife’s powers of physical endurance. Although she looked ‘fragile and delicate’ she could apparently raise from the floor a blacksmith’s anvil by the hair of her head, which she twisted round it; and then, lying down, she would have the anvil placed on her bosom, while a horse-shoe was forged upon it with heavy blows of a blacksmith’s hammer.

“Malcolm’s Anecdotes” (vol. ii.) printed an advertisement for this fair from one of the London papers of the time:—“In Brookfield market-place, at the east corner of Hyde Park, is a fair to be kept for the space of sixteen days, beginning with the 1st of May; the first three days for live cattle and leather, with the same entertainments as at Bartholomew Fair, where there are shops to be let, ready built, for all manner of tradesmen that usually keep fairs, and so to continue yearly at the same place.”

May Fair, which had long been falling into disrepute, was repeatedly faced with restrictions and legal challenges through the reign of George I. It was “presented by the grand jury of Middlesex for four years successively as a public scandal; and the county magistrates presented an address to the Crown, praying for its suppression by royal proclamation.”

In 1721, as we learn from the London Journal of May 27th in that year, “the ground upon which the May Fair formerly was held was marked out for a large square, and several fine streets and houses are to be built upon it.” The idea of a “square,” however, was never realised.

In recording the downfall of May Fair and of its doings, the Tatler announces that “Mrs. Saraband, so famous for her ingenious puppet-show, has set up a shop in the Exchange, where she sells her little troop under the name of jointed babies.”

The year 1700 brought such a disorderly crowd that the magistrates present were forced to send for the constables.

However the 1702 fair attracted a huge attendance, which led to trouble. Apparently an attempt to bar some ‘young women of light character’ from entry resulted in a riot. The young women were arrested by the constables so they could be kicked out, but were rescued by some soldiers; this led a barney, other constables rushed up to join in, “and the “rough element” supported the women. In the fighting one constable was killed and three others seriously injured. The man who actually dealt the fatal blow to the constable managed to escape; but a butcher who had allegedly been active in the fight, was tried for his part in the affair, convicted, and hung at Tyburn. His friends and family fiercely defended his innocence of any crime, and his body was left lying in state in Clerkenwell for some days between his execution and his burial.

|

14-16 May 1702 Westminster, May 16. The Constables of this Liberty being more than ordinary vigilant in the discharge of their duty, since the coming forth of her Majesty’s pious Proclamation against Vice and Debauchery, and having in pursuance thereof taken up several lewd women in May Fair, in order to bring them to justice, were opposed therein by several rude souldiers, one of whom is committed to prison, and the rest are diligently enquired after. [Post Man] 26-28 May 1702 St James’s, May 25. Whereas on Tuesday the 12 of this instant May, a riot was committed in May Fair, in which (amongst other disorders) John Cooper of St James Parish, Constable, being with other Constables and Officers, employed in putting in execution Her Majesty’s Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the Preventing and Punishing of Vice, Prophaneness, and Immorality, he (amongst others) was dangerously wounded, whereof he is since dead; Her Majesty for the encouragement of all such persons as shall discharge their duty in the execution of Her Majestys Proclamation aforesaid, is graciously pleased to promise her pardon, and as a further encouragement, a reward of 50l. to any of the persons concerned in this riot, who shall uncover the person that committed this barbarous murder, and shall cause him to be apprehended and brought to Justice. . . . we hear that 8 soldiers are already committed to the Gatehouse, and one to Newgate, upon suspicion of their being concerned in this riot. [Post Man] 8-10 July 1703 Yesterday [i.e. 9 July] the Sessions ended at the Old Baily, where among several others that received sentence of death, Thomas Cooke the famous prize fighter, was one, who was found Guilty of being concerned in the riot wherein Mr Cooper the Constable was kill’d in the execution of his office in suppressing the publick disorders at May Fair last was twelve month. He was apprehended in Dublin in Ireland upon his own confession, and brought over to be tryed here by her Majesties order. [Post-Man] 20-22 July 1703 Yesterday 3 of the malefactors, who were condemned last Sessions, viz. Peter Dromet, who kill’d his wife, and 2 Women, were executed at Tyburn, but Cook the prize-fighter had a reprieve for some days, in his way to the execution place, and was brought back to Newgate. [Post-Man] 10-12 August 1703 Yesterday Cook, the butcher of Gloucester, was executed at Tyburn, for the murther of Mr Cooper, the Constable, at May Fair. [Post-Man] |

|

14-16 October 1703 The Sessions of Gaol Delivery which began on Wednesday last, at the Old Baily, ended the day following, it being a very small Sessions, two persons only received sentence of death; one of which was William Wallis a Serjeant in the Guards, he being found Guilty of being in the riot in which Thomas Cook the Gloucester-shire fencer was concerned, and for which he was hang’d in August last. [Post-Man] |

This kind of agro helped to bring the fair the discredit, especially among the respectable inhabitants of the neighbourhood of Piccadilly, that would lead to its demise.

Mayfair had indeed become a place of some ill-repute, infested with pickpockets and ruffians looking for trouble, but its bad reputation did not put off attendance at the Fair In 1707, the actor William Penkethman produced a performing dog act announced sensationally in the Daily Courant of the 10th to the 13th May 1707 under the heading “Eight Dancing Dogs brought from Holland” which was an enormous success.

The Grand Jury of Westminster rendered several verdicts on the May Fair in 1708-9, and were pretty clear what they thought of it, describing it as featuring ‘intolerable lewdness’… “Disorderly persons do rendez-vous and draw and allure young persons and servants to meet to game and commit lewd and disorderly practices”

and called it a ‘nursery of vice and atheism’. We’ll drink to that!

|

13-15 January 1709 The Presentment of the Grand Jury, at the General Quarter-Sessions of the Peace holden at Westminster, in and for the Liberty of the Dean and Chapter of the Collegiate-Church of St. Peter, Westminster, of the City, Borough, and Town of Westminster, in the County of Middlesex, on Monday, the 10th of this instant January 1708 [i.e. 1709]. As we are Inhabitants, and most nearly concern’d, so we are most tenderly affected with, and have greatest reason to complain of, the yearly dangerous riots and tumults committed within this City and Liberty, at May-fair; and the rather, because the ordinary course of justice, has been found insufficient to stop the many irregularities, and prevent the great disorders thereof. The presenting and punishing some particular persons (if they could be found) is not likely to produce a sufficient remedy; And whereas the end of the grant is most notoriously perverted, and the same is now kept on foot, to bring together ill-disposed persons who meet there to game, and commit lewd and disorderly practices, whereby many of Her Royal Majesty’s subjects are debauch’d and corrupted, especially the younger people. Upon all which accounts, we cannot try lament that within this Liberty, there should be such a nursery of vice and debauchery, which, as such, we cannot but look upon as a very great misfortune to our selves, our children, and servants, whose habitations are so near the said Fair. We therefore think our selves happy, if, as the Honourable City of London (by the commendable zeal and worthy to be imitated Care of its Magistrates) is freed from the inconveniences of Bartholomew-Fair, the City of Westminster likewise (so nearly allied to it) could, by the zealous care of its Magistrates, be deliver’d from the mischievous Consequences attending May-Fair. Which Address was favourably receive’d by the Bench of Justices, &c. [Post Boy] 30 April—3 May 1709 On Friday last, a Proclamation was publish’d, strictly enjoying the proprietors and owners of May-Fair, that they do not permit or suffer any booths to be erected, or stalls to be made use of, during such time as the said Fair shall be holden, for any plays, shews, gaming, musick-meetings, or other disorderly assemblies. [Post Boy]” |

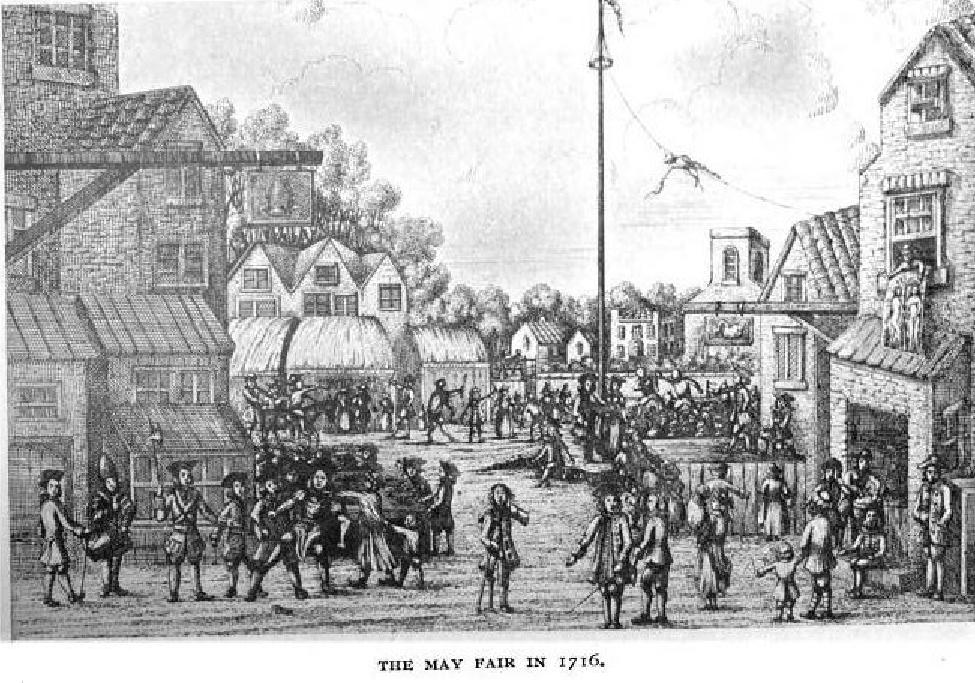

In 1708 the architect Edward Shepherd purchased the land on which May Fair was held (he gave his name to Shepherd’s Market built in 1735). The same year saw the royal proclamation of the 28 April 1708 banning the construction of fair booths “for Plays, Shows, Gaming, Musick-Meetings, or other disorderly Assemblies, [because] several Booths have been constantly built and made use of, during all the time of holding the said Fair, for entertaining Loose, Idle, Disorderly People with Plays, Interludes and Puppet-Shows.” The fair was not abolished, but the troupes of players were refused access. So, there were no theatre performances at May Fair until 1743, but other entertainments were offered to the public during this period. An engraving of the May Fair in 1716, depicts fencers, a violinist, the start of a donkey race and the May pole entwined with ribbons.

1743 saw the return of the theatre people to May Fair and in 1744, Hallam’s New Theatre was constructed near Shepherd’s Market House. An advertising bill, printed in the General Adviser of 1st May 1744, sang the praises of this “regular theatre [in which] Ladies and Gentlemen will be entertained in a more decent and commodious manner than they can possibly be at any booth.” The seat prices were the following : “stage 2s.6d./ boxes 1s. 6d./ pit 1s./ gallery 6d.” Farces, mime shows and comedies were performed throughout the duration of the fair and continued once the fair was over.

But May Fair continued to be the object of violent attacks by the Middlesex authorities. The area had become developed as a series of fashionable squares and the new residents were complaining about the fair. In 1745, a year of more crowd trouble at May Fair, the actors again became the favourite target of the law and were labelled “rogues and vagabonds” responsible for quarrels, fights and even drunken brawls which happened regularly at the Fair. The site owner, Edward Shepherd, tried to restore calm and to prove to grousing neighbours and to the authorities, that order and decency prevailed at May Fair “as it remarkably has been every year since the present Proprietor has had the management thereof” (Daily Advertiser, 2 May 1745 ).

In 1753, the duration of the Fair was reduced to 12 days (from the 1st to the 12th May). In April 1763, the inhabitants of Curzon Street and neighbouring streets signed a petition to demand the suppression of the fair and to put an end to its harmful effects. They did not win the case that year, but when Tory politician and bigwig the Earl of Coventry came to settle in his new residence, located close to the May Fair site, in 1764, he was very soon disturbed by the noise of the fair and used his influence to do away with the fair for good.

The closing down of the May Fair was an early blow in a widespread campaign to impose social and moral control over the disorderly lives of the lower classes. The reforming urge would gather more pace in the 19th century.

National government, local vestries and parish authorities, officials of most churches, and various bourgeois organisations such as the Constitutional Society and the Society for the Suppression of Vice, co-operated in attempts to control and ‘reform’ the ‘immoral’ behaviour of the working classes, especially the poorer sort. This took the form mainly of forcing them into harder work, proper respect for authority and religion, and attacking ‘vice’, disorder and immoral behaviour. ‘Vice’ was to be repressed in all forms- from pubs and beer shops, through prostitution, demolition of whole streets and neighbourhoods deemed unruly, to fairs, and other traditional rowdy gatherings, and theatres (especially those hosting satirical performances), or those who radically challenged religion or the political establishment. Working class entertainment was particularly targeted.

Fairs, widely viewed as hotspots of immorality, disorder and in many cases satirical political plays and speeches, were a prime target. Not only for the crime, sex snd boozing they featured, but in an era of political upheaval and widespread radical agitation among the working class, any gathering of the poor was seen as dangerous.

In previous centuries fairs had had wide economic functions in rural areas- selling animals, produce, hiring of workers etc. But as development and industrialisation led to some decline in this role, and the entertainment side of fairs grew, some of the ‘better sort’ were wondering whether they brought more trouble than they were worth.

The open spaces where Fairs traditionally took place were also under attack, through the enclosure of commons, Greens and the increasing landscaping into parks, or development into housing. The physical alteration of space was seen as having a moral effect on the disorderly behaviour of the poor: proper ordered open space replacing ‘waste’ and common was believed to encourage respectability…

For local Vestries, the high cost of policing the Fairs and cleaning up afterwards were also expensive, and local ratepayers (the wealthier locals) were increasingly unwilling to subsidise the cost.

Later repression of fairs resulted in furious debate and in some cases, attempts to hold the event even after it had been banned.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@

After Mayfair had been cleansed of the freak shows, performances, riotousness and bad behaviour the old Fair had encouraged, the area was rapidly transformed into a very posh neighbourhood, home to some of the country’s wealthiest regimes and most exclusive hotels & clubs. (Moving the bloody spectacle of public hangings at nearby Tyburn , with all the death carnival crowds they attracted, in 1783, probably also helped up the tone of the area quite a bit).

The rich were moving ever west in London, and flocked to the elite estates created by the likes of the Grosvenor family. Money still drips here like the sweat off (many other people’s) brows.

An attempt to invade the area and revive the spirit of the May Fair was made in 2002, when the annual anti-capitalist Mayday festival of alternatives commemorated disorder and resistance to the wealthy here, with circuses, a mass Street football game and a Wake for Capitalism, among other fun happenings:

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply