The South London Women’s Hospital Occupation 1984-1985

Rosanne Rabinowitz

[Originally written around 2003]

What does it take to occupy a hospital, to engage in direct action in a workplace that deals with peoples’ lives rather than products? In the first hospital work-ins, people were understandably afraid of putting patients at risk, and aware that someone might not want to have a baby or an operation in the middle of an industrial dispute. It was an unprecedented step, but staff and service users had come to a point where they felt they had to take drastic action or say goodbye to their jobs and healthcare.

A background of cuts and closures provoked this first wave of occupations in the 1970s, often undertaken by people who were not activists. In the early 1970s both the private and private sector were restructured in response to IMF directives. The restructuring was also a move to curtail the improved wages and defences (‘restrictive’ work practices) that workers built up through the years. This took the form of further centralisation, deskilling, redundancies, productivity deals, speed-ups, casualisation and tougher discipline.

Since this restructuring often involved closures, people began occupying workplaces instead of simply going on strike. Some of these actions developed beyond sit-ins to work-ins, which involved continuing production. Briants Colour Printing and Upper Clyde Shipbuilders were among the first work-ins. UCS became a rallying point due to the size and its location in area of militancy and close ties between the workplace and the community. Shop stewards seized control of the yards and controlled the gates on a rota. Those sacked were kept in jobs by rest of workforce who now controlled production. The fact they were already sitting on top of a lot of capital and unfinished work made this possible.

Over 1000 occupations & work-ins took place in 1972. However, in some situations self-management can turn into self-abuse. A cartoon of the time said it all: “Brothers and sisters! If the bosses won’t exploit us, we’ll have to do it ourselves!”

However, work-ins also included community outreach and political organising. For example, at Plessey’s River Don steelworks redundant workers devoted themselves to campaign work rather than completing orders for the plant’s liquidator.

From private to public…

A twist in the tail came when hospital work-ins and occupations extended this tactic to the public sector. In the face of such closures, a strike presents problems unless it takes the form of sympathetic action in other hospitals or workplaces. However, by providing a service that management was trying to cut, workers strived to create a rallying point.

Usually, hospital workers contemplating a work-in discussed it with present or prospective patients. This is more of a possibility in smaller, long-stay hospitals.

As long as patients are in a hospital, the Secretary of State is legally bound under the Health Services Act to ensure that they receive treatment and to pay all the hospital workers; nurses, doctors, technicians, cleaners… So by keeping patients in the facility, hospital occupiers were able to keep the hospital open and functioning.

However, there is the problem of insurance. Insurance rules stipulate that management must be present on the premises and be legally liable and responsible. This could include area health authority representatives or on-site administrators. During the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital work-in, the on-site management consisted of the hospital secretary.

The employees in a hospital work-in usually acquire more power, but this occurs alongside a functioning administration. Some hospitals did refuse entry to most of management and allowed only a token management force that would not be able to obstruct the work-in.

In order to keep a hospital occupied, you need physicians willing to admit patients and treat them. Some physicians did remain in service in accordance with their concept of professional ethics – if there are patients, they will care for them. But they generally stayed away from political aspects of a campaign.

Two hospital earlier work-ins have particular relevance to what took place at the South London Women’s Hospital: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital (EGA) and Hounslow Hospital.

The first: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital (EGA)

Founded by the UK’s first officially practising woman doctor, the EGA aimed to train women doctors and provide treatment for women by women. Closure of the hospital, located on London’s Euston Road, had been contemplated since 1959 on grounds that a woman-only hospital was an anachronism of the Victorian era. The authorities considered demand limited to small groups of orthodox Muslim & Jewish women who objected to treatment by male doctors for religious reasons. There was also a drive within the NHS to ‘rationalise’ and to close down small hospitals.

However, they hadn’t reckoned with a growing women’s movement that made medical care for women by women a central issue. Debate had also grown about the very nature of women’s healthcare, as seen in publications like Our Bodies Ourselves.

Throughout the 1960s Health Authority ‘ran down’ the EGA by not doing repairs, replacing equipment or hiring new staff. Bed space had declined from 300 to 150. A malfunctioning lift in 1976 brought patients down to 46 and closed off the operating theatre. The hospital faced a succession of closure threats. Demonstrations and a petition signed by 23,000 women forced the nursing council to back down from closure in 1974. However, the EGA maternity hospital had been closed down, and this had angered staff members. They formed an action committee that represented different sections, but it was dominated by the consultants.

EGA was a good place for trying the occupation tactic in a hospital setting – its unique historical legacy as a women’s hospital created ground for support and unity. The women doctors at EGA also tended to be progressive – for example, one had received her medical training as an anti-fascist volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. This committee’s main tactics involved lobbying, petitioning and writing letters.

The rest of the staff got involved after actual closure was announced in 1976. This included the big health unions: the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE), COHSE (representing nursing staff), and ASTMS (paramedical staff). In July 1976 health workers protested against health service cuts and the EGA closure in particular: 700 workers staged a ‘day of action’ and marched to the House of Commons. Others took action in their hospitals, forcing four London hospitals to restrict admissions to emergencies. Some occupied health authority offices. Rank-and-file groups took on a major role organising these actions. Future New Labour health minister Frank Dobson was then leader of Camden council and voiced support. Wonder what he’d say to an occupation on his patch now?

However, health secretary David Ennals claimed that the EGA was ‘small, ageing… can never be developed to fulfill functions of a modern, acute hospital and suggested the EGA become a unit at the Whittington Hospital in Highgate.

The Action Committee replied that the EGA’s present location allowed it to function as a specialised national facility and a centre fulfilling local needs. As a small hospital maintained “a friendly, unthreatening atmosphere, necessary for a hospital interested in educational, preventative and outreach work relevant to the specific health needs of women.” The committee also pointed out that residents in the nearby Somerstown estate were pressing for their own health centre; facilities for women at the EGA could take pressure off the Somerstown health centre. Increasingly Somerstown residents and EGA campaigners worked together.

When Ennals asked the Area Health Authority to close in-patient services at the EGA, staff held an emergency meeting vowing to sit-in or work-in if necessary. The work-in had been urged by community activists (not staff members) on the EGA campaign committee, but was rejected as impractical in a hospital setting. But as closure loomed, the staff and community seized on a work-in as their last chance. It began a few days before the actual closing date with official support from the unions.

In November 100 nurses and 78 ancillary staff began the occupation. Pictures taken outside the EGA on that day show pickets in front of the hospital with a banner declaring: “This hospital is under workers’ control.”

Meetings of all the staff made major decisions, with committees set up by general meetings to do the actual organising. These included the Joint Shop Stewards Committee, the Medical Committee and the Action Committee; the latter made up of elected representatives of all sections of staff, and linked union members and consultants.

The Save the EGA campaign committee consisted of supporters outside the hospital. Though set up by Camden Trades Council, it became autonomous and drew in people from other hospitals, local residents, people involved in childcare and housing campaigns – such as the nearby Huntley St squat – and activists from the women’s movement. One shop steward participated in campaign meetings, and the campaign sent a representative to other groups. This committee main support for working in came from the campaign committee.

Ambulance drivers and workers in referral agencies such as the Emergency Bed Service were vital in opposing management attempts to stop the flow of patients into the hospital – workers notified drivers that the hospital remained open and asked them to bring patients.

More than defence

Work-ins are essentially defensive. They aim to keep the premises in repair, maintain morale and keep equipment and patients in the hospital. They are not set up to implement ‘workers’ control’ or transform social relationships within the hospital. But staff usually do gain more influence as a group, and ancillary workers and nurses develop stronger organisation.

In order to involve more people in the campaign, activists usually need to progress beyond defense to demand extensions or improvements in the public resource. Direct action to preserve a service or facility inspires debate on the role the facility plays in a community, the needs it fulfills and the needs it must be developed to meet.

In the case of the EGA, this expansion took place in the context of the women’s movement, defining the EGA as a women’s hospital and a national and local health facility. This resulted in pushing for a well-woman’s clinic that takes a community-oriented approach to health and act as an information centre as well as medical facility. According to Rachael Langdon of the EGA Well-woman’s Support Group:

“The dissatisfaction experienced by women in health care will not be overcome alone by seeing a doctor of one’s own sex or only by the existence of a women’s hospital. The issues are wider and preventative health is not merely a matter of individual effort. This is where the importance of alternative and women’s movement health groups lies… A well-woman clinic and a women’s hospital which could develop an exchange of ideas and knowledge with alternative and women’s health groups would be a step forward for women’s health.”

Campaigners demanded that the EGA be upgraded to a ‘centre for innovation and research’ in women’s health matters and a resource in the community. Campaigners and workers sponsored well-attended discussions relating to women’s health issues such as menopause and contraception, which often drew over 200 people. Sometimes the discussion between doctors and radical feminists set on challenging the medical establishment got lively.

More closure threats arrived in 1978; in May, a large demonstration in front of the hospital stopped traffic on Euston Road. In 1979 campaigners won the battle to keep the EGA open as a gynaecological hospital. However, the old building closed in 2008 and EGA now operates as a specialised maternity wing within the UCH hospital.[NB: This unit remained open as a separate building in Huntley Street until 2008, when it was moved into the new University College Hospital building just down the road. Your past tense typist’s daughter was among the last people born in the second EGA.]

Both the EGA and later the South London Women’s Hospital campaigners had ongoing debates over whether they should plead as a special case, or defend their hospital as part of an across-the-board opposition to health service cuts.

For example, people in the EGA campaign group believed that campaign should ‘feel free’ to split from the staff action committee if it didn’t not take a direct line against the cuts; they felt the campaign should take the initiative, which hospital workers could follow or not follow. They believed the campaign was responsible to those who used services, which expressed itself in total opposition to the cuts and transcended the interests of workers in saving their particular hospital.

Hounslow Hospital

In contrast to the EGA, West London’s Hounslow Hospital did not have the advantages of national reputation, special support from the women’s movement or supportive consultants. It was a small facility for geriatric and long-stay patients, considered a home as well as a place for treatment. Situated in an industrial area, girdled by two motorways and Heathrow Airport, Hounslow faced more repression and practical disadvantages.

The authorities had backed down from closure threats to EGA at least three times and did not attempt to break the work-in, outside of morale erosion and running down facilities. Hounslow workers faced constant threats and intimidation, a forcible smashing of the work-in.

With less support from doctors, Hounslow staff including nurses, porters and cleaners and took the main initiative and challenged the traditional hospital hierarchy. The work-in only lasted six months, but the community occupation of the hospital that followed lasted two years. Lines were drawn clearly, and there was no special pleading.

The response to proposals for possible closure in 1975 started with admin staff and friends, plus local volunteer and charity organizations, who wrote letters and circulated petitions – usually hand-written sheets passed around the neighbours. Senior nursing staff took an interest, opening communication with ancillaries and porters, and these involved workers from ‘outside’ in the campaign. Activists from the West Middlesex District General Hospital looked into plans and discovered a whole series of cuts planned for the region.

Hounslow’s closure was announced in January 1977, set for August; the work-in started in March. Management tried to transfer staff, and threatened those who refused with sanctions & sacking. They met with GPs, warned them against admitting patients to Hounslow and threatened them with sanctions.

When the August closure date arrived, staff organised a march through Hounslow and a party for the patients. As they pushed past the closure date there was a lot of fear. Workers had no idea if they would get paid; the authorities tried to claim that the AHA did not have to maintain staff and facilities though the law said otherwise.

Comparison and clampdown

The EGA had on-site consultants who could admit patients; Hounslow had none and depended on GPs. They had to tout for more admissions, though August is traditionally a slow time. The authorities tried to turn patients away and cut off the phones. The EGA had been treated as a freak case, but Hounslow indicated a trend of resistance to health service rationalisation. If a small weakly-organised hospital became such a focus for community resistance, they saw obstacles to imposing any cuts and rationalisation. The Hounslow work-in had also gone further to challenge the hierarchical relationships of the hospital. Consultants weren’t around much, and the process of campaigning had broken down traditional boundaries. The campaign and the staff had effectively taken over control of admissions. As one Hounslow Hospital worker put it: “With consultants no longer in control of admissions, the hierarchical system of privilege in the NHS was smashed.”

When threats didn’t succeed, a district team of officers took forcible action on October 26, 1977. If the authorities had to continue funding as long as patients were present, they got around that by forcibly removing the patients. Aided by the private ambulance service (public ambulance staff refused to take part), police administrators, top nursing officers and consultants moved on the hospital. They cut the phonelines, thwarting the emergency phone tree. The raiders pulled 21 patients out of their beds and took them to the private ambulances. Pictures show the scale of destruction – wrecked beds and furniture, the floor strewn with food, torn mattresses, sheets, personal articles. According to a nurse: “Old ladies had to queue up for an hour, crying all the time, as we remonstrated with the AHA people to cover them against the cold.”

The raid provoked a public outcry and led indirectly to the downfall of Hounslow’s Labour leader. A week later 2000 striking hospital workers picketed the Ealing, Hammersmith and Hounslow AHA to protest the raid and demand reopening. The AHA had to censure their own officials and called for a public enquiry, which was turned down by David Ennals. The district administrator later admitted that losing the 66 beds had badly affected geriatric care in the area.

Complete control

Once the hospital was shut, campaigners moved in and took complete control of the building. They had little idea what to do with it now that the patients gone and wards wrecked. Eventually they cleaned it up and used it as a local centre. Some of the original staff continued to be involved with the occupation. With the end of the occupation two years later, five were left.

However, the occupation itself drew in new people and took on a life of its own. Following the raid Hounslow had become a national issue. Nurses, porters and food service workers traveled to hospitals and meetings throughout the UK, discussing their experiences and asking for support. They initiated a national campaign against NHS cuts, called Fightback, based at Hounslow and involving people from the EGA, St Nicholas, Plaistow and Bethnal Green work-ins.

The Fightback production team occupied the matron’s office, the West London Fire Brigades Union used the assistant matron’s office as their headquarters, Maple Ward became a ‘conference hall’ used by local groups. The National Union of Journalists used hospital facilities during a strike.

The occupation became very intense, given the strong emotions provoked by the raid, the length of time the occupation carried on and the variety of groups taking part. Women whose world was defined by husband, family and job found themselves making speeches and going out every night, confronting their husbands to go on tour or to stay overnight at the hospital on night picket. Seven marriages broke up in the course of events, and many new relationships started.

After a year of occupation, AHA backed down on the eviction threats and conceded to negotiations on the occupation committee’s demand that Hounslow Hospital be reopened as an upgraded diversified community hospital, based on plans that had been developed during the occupation. The occupation committee did not negotiate as a special case. The opening of a community hospital meant little if cuts are made elsewhere. These negotiations broke down when management did not give firm dates to provide plans, or guarantee commitment of funds.

However, the committee ended the occupation in November 1978, claiming that ‘no positive political gain’ would come from an eviction. They thought the demands of maintaining a 24-hour picket were draining resources from other kinds of campaigning, and diverting attention from cuts in other areas. They claimed some victories in dislocating the programme of cuts and put forward detailed plans for an expanded community hospital. In its statement, the committee said that work began on redesigning facilities in the new community hospital/health centre after the occupation ended.

In 1976-78 work-ins or occupations took place in at least ten hospitals. About five work-ins were waged over an extended period of time to oppose closure, and the rest were shorter actions to oppose under-staffing and back up other staff demands. There were also sit-ins in administration and health authority offices, including an eight-week occupation at Aberdare Hospital, and in one nursery school and an ambulance station. Occupied hospitals included Plaistow Maternity Hospital, two wards at South Middlesex and one at Bethnal Green, where local people assisted the work-in by occupying the wards that had already been closed.

Some participants pointed out that union officials definitely got in the way during work-ins, hindering rather than helping in open-ended struggles where people need to keep things going and maintain morale. Union officials think in terms of ending it all and negotiating the terms. According to one participant, union officials that came into Hounslow when the work-in was made official “caused more havoc than management.”

South London Women’s Hospital: don’t be so kinky

Many of the occupations of the late ’70s had achieved short-term goals; and some work-ins were defeated due to lack of support from consultants. However, use of the tactics trailed off by the early ’80s. Until…

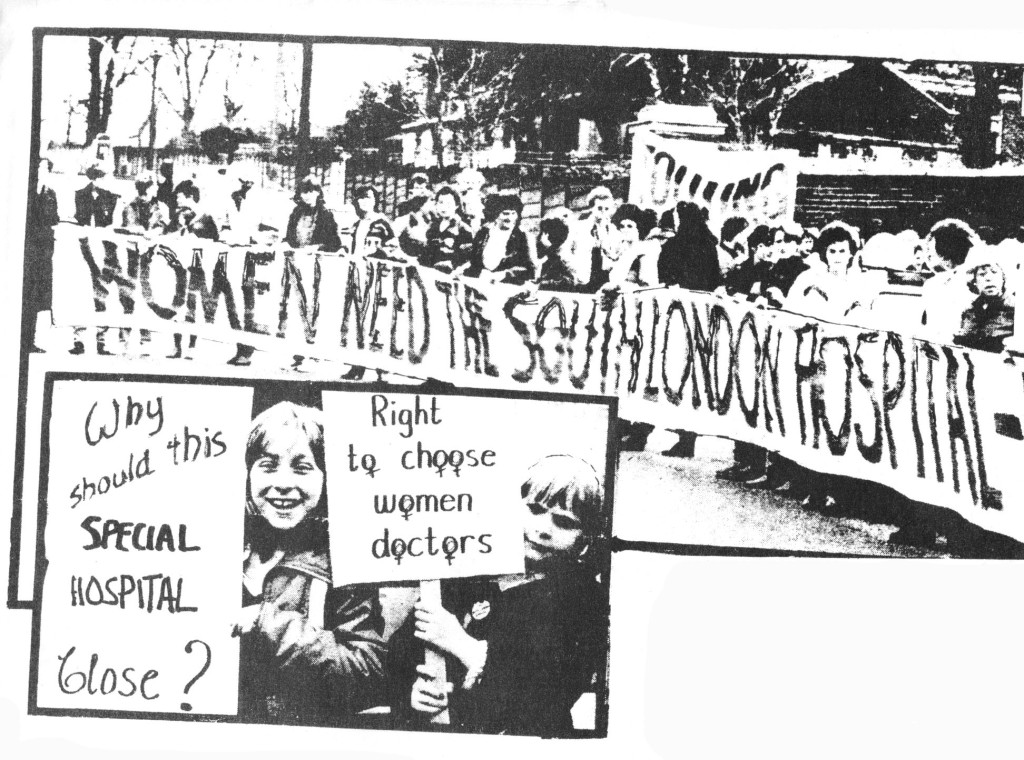

The Wandsworth Health Authority announced in 1983 that it will close the South London Hospital for Women’s (SLHW). This hospital had some similarities to the EGA and similar issues came up in defending it. However, this time around the authorities couldn’t say that a hospital where women receive treatment by female physicians was a remnant of the Victorian age. Instead, Wandsworth argued in terms of rationalising and budgets.

Staff initiated a work-in late spring 1984, which only lasted a couple of months. Fewer consultants were admitting patients, then the consultants were all offered positions elsewhere and they jumped ship.

But nurses and other staff wanted to fight on. Together with local activists they organised a “lie-in” in July 1984, following the exit of the last patient. The outpatients’ department (housed in an adjoining building) was due to shut later, in spring 1985.

I found out about the campaign to save the hospital when I went to the well-woman clinic and found a stack of leaflets there. This might have been when the work-in was still going on.

A good 200-300 women came to take part in the lie-in. We slept in the wards and maintained a mass picket to stop the authorities from removing equipment. All the large wards were filled. The top wards were kept empty as an example of what the fully-equipped wards could be like.

In the absence of patients, the occupation aimed to keep all the equipment on site in readiness for re-opening. Though a relatively small hospital, SLHW was a large rambling Victorian building with many entrances and exists. We maintained a picket at the main front door, locking the other doors in the main building, and also kept a picket at the gate in the car park.

There was still a lot of coming and going in relation to the outpatients as well as security guards still stationed at the front.

All kinds of women took part in this event – local pensioners, hospital staff, nurses, anarcha-punky girls. It was also racially and culturally mixed. I met a few women who said that they’d been born in that hospital. There was a fun atmosphere, with lots of people sitting outside on picket. It was a warm summer night, so people also relaxed in the garden.

Unfortunately, the next day a few snotty social worker types scolded girls for fooling about on the water-beds when the press was due to arrive. “Don’t be so kinky,” one of them said.

Of course, when no attempt was made to evict us the next day, we had to decide how to continue the occupation and how to organise it. First, what to do about the security guards. During the first few nights of the ‘lie-in’ they were doing rounds throughout the building while we were sleeping, walking around and shining their torches and speaking on their walky-talkies (this was the 80s, remember). We had some tense negotiations about this, but eventually they agreed to stay in their office on the bottom floor.

Numbers were still high for the first couple of weeks, but as you might expect they started to dwindle. It became a strain to maintain the picket. After the third week or so the health authority informed us that they wouldn’t be evicting us while the outpatient facility was still going. Obviously, the authority knew it would be easy for us to get back into the building if part of it remained open to the public. The health authority insisted that the security guards remain downstairs, but as they’d been keeping to their area it wasn’t a problem. Not a bad gig for them really, with the pickets keeping an eye on things they didn’t have much work.

Since the days of the EGA the women’s movement had diversified and grown. Women came from the Greenham Common peace camp to support the occupation. One lot got annoying when they told us we should have non-violence training. It seemed to be imposing their way of organising on us. At the same time, a bunch came from Blue Gate who were more down-to-earth. By this time, each gate at Greenham had their developed its own character and politics.

There had been a lot of Labour lefty influence in the beginning, which might have reflected elements of the campaign before I got involved. We were living in the days of the GLC, after all. We got visited by GLC Women’s Committee chair Valerie Wise, who gave speeches in front of the hospital. She kept saying: ‘My name is Valerie Wise, and I’m here to talk about the GLC.’ Some of the women there were chuffed by this, though her constant self-promotion made me sick. In fact, I was having some doubts about staying on if we’d be hearing a lot of this.

Then I went on holiday for about ten days. Just after I returned, I was in bed recovering from an all-night train and ferry experience. Then I received a phone call that emergency pickets were needed at the hospital. Already? I’d meant to give it a few days before going down again, but my caller said it was very important so I turned up.

A bunch of new people were on picket, and I found out someone was having a baby upstairs with a midwife in attendance. When the baby was born, celebrations ensued and then the TV bods turned up. The baby was a little girl called Scarlet.

A whole new bunch of women infused the campaign. Some had just moved to London, and they made themselves at home in the wards with the private rooms. This inspired a general movement to occupy the wards upstairs, and use the big lower wards as communal and social areas. With the involvement of new and full-time occupiers we entered a new phase.

Taking a tip from the Hounslow experience – among our local supporters was a nurse who had been active in earlier health service struggles – we made the hospital into a campaign centre and a kind of social centre a well. We invited other groups to use the space, and held activities like jumble sales, tea dances and public meetings. We had a big picnic in the garden with performers – among these was Vi Subversa, singer from the anarcho-punk band the Poison Girls. The first jumble sale was massive, with bags & bags of stuff that made us a good £500 and costumed the entire occupation group too.

A radical nurses’ group had been active for some time; an Asian women’s health group also met there and did acupuncture. Some of these activities kicked off quickly, other things took a while to get going.

The occupation went through several reorganisations, but we made decisions at general meetings throughout. When a lot was happening we had general meetings every evening, but this wasn’t always necessary. We set up groups involved with particular tasks _ publicity & propaganda, coordination, outreach & campaigning, looking after the building.

Since we were entering a phase with a definite long-term commitment, everyone eventually moved into the private rooms in the upstairs wards and left the big wards for communal purposes, meetings and events, And just like the gates at Greenham, each ward took on its own character.

The top floor ward in the main building became known as called Cloud Nine. It was favoured by the spaciest Greenham girls, mostly from Green Gate. Most of these women were great, but some of us got impatient with a few who came to the hospital to chill out (or warm up, during the winter) and didn’t take part in the picket and other activities. From their point of view, they came from the rigours of Greenham to have a rest somewhere warm – with outpatients still open, the central heating and hot water remained still on. Greenham was their main commitment. Yet the long-term occupiers of Clapham felt that maintaining a viable picket was crucial in keeping the building open, and everyone should help with that. It didn’t help when some of our guests seemed to regard the picket as an answering service.

Preston House was a separate annexe reached through a tunnel or a separate front door _ this took the overspill from Cloud Nine. One of the wards – I forget the name – was populated mainly by local campaigners who’d been there at the beginning, including a contingent of nurses.

Chubb Ward, where I stayed, seemed to be popular with young urban-oriented activists.

Coudray was on the ground floor. This turned out to house mainly straight women with babies, though there were lesbian mothers as well in Chubb and other wards. Quite a few of the Coudray women and children were the offspring of a woman called Antonia, who had been involved with squatted street Freston Road or Frestonia.

There were a lot of new relationships going on, amid a high interest in feminist & lesbian politics. With all this going on, sometimes we got inward-looking. However, there were plenty of occasions when we ventured out of the building. We went to most health authority meetings, usually to ask awkward questions and be disruptive. Just after the eviction we went to one meeting and got so enraged at the attempts to ignore the issues brought up by the eviction, we ended up storming the platform and throwing chairs at the authority bods. If there’d been a dominance of polite Labour leftism in the early phases, as time went on the occupation became more militant and radical.

Other hospital occupations had also sprung up, including a work-in at a geriatric hospital in Bradford and occupied A & E at St Andrews Hospital at Bromley-by-Bow. We came out to support these actions. We also supported a picket at Barking Hospital, where an anti-casualisation struggle had been going on for over a year.

During the miners strike of 1984-5 we made contact with Women Against Pit Closures and some of them came to visit the hospital, including women from Rhodesia in Nottinghamshire and from Dinnington in South Yorkshire .

On one hand, we were reaching out to other movements and resistance, but we also faced issues in how we worked within the occupation. Because the building was warm and comfortable and any woman could stay there, it drew many who were fairly vulnerable. So while we defended health service provision, we often found ourselves providing the kind of support that should be coming from these very same services. Women had different attitudes towards this. Some didn’t want to take this on and wanted to concentrate on the political campaigning. Others felt they had enough on their plate and couldn’t take on caring for others even if they wanted to. And then some women got very involved in the ‘caring’ of the campaign and those who didn’t participate were evading their responsibilities.

There were also arguments around sharing childcare. And since this was the ’80s, rows over identity politics broke out. So it wasn’t all fun and parties and solidarity. Certainly, morale was very low about a month before the eviction. Let’s face it, there was a lot of bitching… petty arguments over which ward got the TV, that kind of thing.

We were also worried about how vulnerable women would fare if the place gets stormed by the cops. Most left when they realised that things were going to get hot.

In the case of one woman with mental health issues who wouldn’t or couldn’t leave, her sister came to take her and had her sectioned, fearing she’d fare worse if she waited around and let the cops do it. We resolved to keep tabs on the woman’s care and visit her in hospital. Debates raged over whether this was a positive or thoroughly despicable outcome

It didn’t help that others came along and used the occupation as a hotel: for example, one lot of American women’s studies students kept asking ‘How often do they change the sheets here?’

Meanwhile, the date of the outpatients closure drew closer and eviction became a real threat again. After we publicised the situation, once again new women turned up and they were ready to kick bailiff ass! Rallying from a depressing period, the occupation became vital again.

As soon as the outpatients closed, we took control of the whole building. We went down to the lobby as a group and got the security guards to leave. There were some tense moments, but they left without much argument. Then we took over the phones, the switchboard and the communications network – this included some walky-talkies, which excited us immensely in the olden days before everyone had a mobile phones.

There had been many discussions about tactics. Some women did not want to do barricading and engage in any resistance, or were not in a position to do this. Though they withdrew from the building before the barricades went up, they still put themselves on the phone tree and took part in picketing and demonstrations.

One woman called Sharon insisted that she’d lie down in front of the cops and use her body as a barricade, though she opposed any other kind of barricade. We all thought that would be extremely dangerous, and tried to talk her out of it but she insisted even more and got very shrill and even abusive. At that point, we had to ask her to leave and eventually carried her out bodily. I mention this because it’s important to record the disagreements and fuck-ups.

We planned to barricade the entrances, leaving only the big front door with a movable barricade, a great heavy beam. Women would barricade themselves into particular wards, while a mobile group would turn fire hoses on the bailiffs and chuck sawdust and then go up to the roof of the main building. Another task of this group was to make sure women who wanted to leave got out when the bailiffs arrived.

One thing that sticks in my mind now is how we strived to organise so women could do whatever they were prepared to do and set their own limits as much as possible. For example, those who could not risk arrest volunteered for look-out shifts in a van nearby. There was never any sense that certain actions were more important than the others; we all pulled together.

Every afternoon we held rallies in front of the hospital, passing out leaflets, talking to people, speaking out and singing. Some of us hung out on the balcony over entrance, dressed in hospital uniforms and surgeon’s masks and sang songs like “what shall we do with the cops and bailiffs”. It was very fun and theatrical.

We were in a constant state of alert, and many false alarms came through on the walky talkies. I remember code names like “Merrydown” and “Spikeytop”.

Once we had a report that someone was digging up the electricity in the road, and we swarmed out (with our masks on, of course) to confront the folks alleged to be doing it – and it turned out to be ordinary road works. Most local people were very supportive and people from other hospitals turned up to help picket. A miner who we met in at the Bradford hospital occupation also turned up. He seemed embarrassed when he realised it was a woman-only occupation, but we sorted him out with a local miners’ support group.

However, I should mention we had harassment by homophobic schoolboys. This minor annoyance wasn’t enough to dent our enthusiasm.

The all-out barricading effort continued. We gathered loads of wood and hammering rang out throughout the building. While we were barricading the former outpatients building, we poured vegetable oil on the floor and added dried soybeans to make it all slippy-slidey for the bailiffs.

Since we were very security-conscious, we wore surgeon’s gloves and masks while performing these operations. One evening while we were barricading, a group of alternative video-makers were following us around. We were just about to use some cabinets and trolleys for barricades, then the video-makers insisted we wait for them to film the rows of trolleys to portray “all that is lost”.

I would love to get hold of those videos, but I don’t remember the names of the women who were on the team or the name of their group.

For safety, we all moved out of the private rooms upstairs and everyone slept in the big Nightingale ward again. After many desolate nights when only a few people held the fort, pickets involved over 30 women or so. They became very party-like. The mobile group, which I was in, slept in a room downstairs near the door, so we had the partying near us all night. But sleep? Did we need it? Not then, nah…

Meanwhile, the nurses’ station in the communal ward acquired extra curtains and became known as “the bridal chamber”. Lots of relationships started… ended and started in this period.

The eviction date came and went, and we were still there. We put on a party to celebrate (Sleaze Sisters, regulars at the Bell, did the DJing), and started to make plans again. We turned the first floor ward into a place to relax, painted a mural on one wall and gave each other massages; we disrupted another health authority meeting. Some of the groups that had been running events at the hospital returned to put them on again.

But three weeks later, the hospital was evicted on 27th March 1985 by 100 male cops and 50 female cops. By then our numbers had gone down from about100 to 30, but we still made a good stand. After the usual false alarms a phone call came through the switchboard with a tip-off. This one turned out to be true and the bailiffs arrived at 3.15am.

As planned, women barricaded themselves into wards, while the mobile group barricaded the last door and stairs.

Another group of women occupied the roof of Preston House. Meanwhile, a small crowd had gathered in front, summoned by our phone tree. I’ll mention at this point that we did get support outside the building from men. A local activist called Ernest was very prominent in this – later he took part in Wandsworth anti-Poll Tax organising and went to jail for non-payment. I remember him shouting at the cops: “why do you have to be so macho?”

Our group ran up to the top floor, turned on the waterworks at the cops and bailiffs though sadly the water pressure wasn’t up to much. We went to the roof and threw the last barricades in place and sat on the cover to block the ladder leading up to the roof. We heard women shouting and singing from the Preston House roof and the balconies. Smoke bombs and fireworks went off. Then the banging started below as cops and bailiffs hacked their way through the barricades. It took them about two hours to get to us up off the roof.

In the press a lot was made of the use of women coppers – it was called “the gentle touch”. Not that it matters much, but the policewomen played a subordinate role. Male coppers dragged us down from the roof. Whatever their gender, the cops were big on arm twisting and made a big show of starting to nick us: “Prepare to receive prisoners” then pushed us aside near the vans. However, they did cart off two women. There was lots of pushing and shoving and some fighting in an attempt to save the two women.

Later, we picketed Kennington Police station where the two women were held. They were released after two hours, though they’d been roughed up while in custody. We then picketed Cavendish Road police station where the cops were holding a press conference on the eviction.

After the picket, some of us were walking to a café near the hospital. As we went past cops hanging outside the hospital we saw them arrest one woman and we went to rescue her, which resulted in six of us getting arrested. A bunch of schoolgirls saw what happened and they were so angry about it they tried to help and got arrested too. They were taken to the police station, strip-searched and held for six or seven hours, and released with cautions. The active role of the school pupils in this melee makes me think of the 2003 anti-war school walkouts and more recent agitation over the education maintenance allowance.

Afterwards…

A clause in the hospital’s freehold stipulated that the building must be used for the benefit of women, and it was also a listed building. Wandsworth Council had tried a number of plans – one was to turn it into a hotel – but the clause got in the way. It was empty for over twenty years after the eviction.

The last plan was building a Tesco’s on the site, which is on the border of Lambeth and Wandworth, but within Lambeth jurisdiction. There’d been local opposition and an appeal against the permission was lodged, but it was turned down and the Tescos went ahead. The development included flats above the supermarket – I’m not sure if it is private or social housing – which might have something to with how the project got past the conditions.

We did make an attempt to continue a health-oriented action group. We managed to get a very small grant and a meeting place in a disused bunker in front of St Matthews Meeting Place in Brixton. We had a public meeting that was reasonably well-attended. But it is most memorable because it took place on the day a riot broke out in Brixton after Cherry Gross was shot (and permanently paralysed) during a police raid.

But this group fell apart. Perhaps, with the end of the occupation itself, the transforming element of the action was gone. Political and personal differences affected the group more, and it seemed time to move on…

However, I won’t end on a totally downbeat note. The eviction of the hospital led to an influx of women settling and getting active in the Brixton area. Much of this was around squatting and housing, and the growth of a new feminist and lesbian community inspired by that. A host of DIY and feminist projects sprang up. Culturally, this was important to women who’d been alienated from boy-dominated politics and the ‘official’ lesbian and feminist scene.

In retrospect, several things distinguished this occupation. The nine-month time span of the occupation allowed it to grow into an important point of contact between groups who might not have worked together otherwise.

In the EGA campaign there had been disagreement over whether to promote the hospital as a special case – a women’s hospital. Or to take it up in terms of opposing all cuts. Though it took some time to arrive at this point, at SLWH we included both the feminist dimension and a strong anti-cuts class struggle element. Our banners said ‘Stop these murderous cuts’. We stressed the women’s health angle as a central part of this opposition and organised events and workshops relating to this.

Another thing that strikes me is that we were able to arrive at consensus in our most heated discussions and everyone had opportunities to speak and express themselves. Given some of the excruciating, highly extended experiences of consensus decision-making I’ve been involved with since then, this seems incredible now. Or am I looking at this through a rose-coloured telescope?

We were ahead of our time with our planning for ‘diversity of tactics’ – allowing for more confrontational tactics alongside ‘fluffy’ ones. Back in the ’80s this wasn’t really done. So I’m proud that we made a break with the binary of pacifism vs ‘violence’. Within the diversity, we placed equal importance on the different tactics and didn’t elevate one above the other. In the early 2000s anti-capitalists planned actions with different blocks using their choice of tactics; several years later the particular blocs and tactics may have become stuck in a rut and lost their effectiveness. However, the core principle of tactical diversity is still a good one.

More recently, Greek health workers have occupied a hospital in response to austerity and health cuts. And with further cuts and privatisation going ahead here, this is a good time to look into this history and see what lessons can be applied now.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

This text originated in a talk at the South London Radical History Group in 2003. It was later updated and published in a past tense dossier on UK hospital occupations, Occupational Hazards. Which is still available to buy in paper form here, or can be downloaded as a PDF here

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2014 London Rebel History Calendar – Check it out online

Leave a comment