“In the beginning of Time, the great Creator Reason, made the Earth to be a Common Treasury, to preserve Beasts, Birds, Fishes, and Man, the lord that was to govern this Creation; for Man had Domination given to him, over the Beasts, Birds, and Fishes; but not one word was spoken in the beginning, That one branch of mankind should rule over another..

…we begin to Digge upon George-Hill, to eate our Bread together by righteous labour, and sweat of our browes, It was shewed us by Vision in Dreams, and out of Dreams, That that should be the Place we should begin upon; And though that Earth in view of Flesh, be very barren, yet we should trust the Spirit for a blessing. And that not only this Common, or Heath should be taken in and Manured by the People, but all the Commons and waste Ground in England, and in the whole World, shall be taken in by the People in righteousness, not owning any Propriety; but taking the Earth to be a Common Treasury, as it was first made for all.”

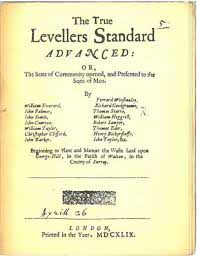

(The True Levellers Standard Advanced, 1649)

On April 1st 1649, a small group of men and women moved onto wasteland at St George’s Hill, near Weybridge, in the parish of Walton-on-Thames in north Surrey, and began to dig over the land and plant vegetables.

This followed a brief prelude when on a Sunday, (either a few days before, or on April 1st itself) several soldiers had invaded the parish church at Walton, startling the congregation by announcing that the Sabbath, tithes, ministers, magistrates and the bible were all abolished. To disrupt the pious sermons of the parish was shocking; just as outrageous to religion was to disrupt the Sabbath by digging the land. The group carrying out such actions knew they were flaunting their questioning of conventional religious practice, as well as challenging the ‘common’ assumptions about use of land. Pun intended.

On April 2nd, several other people arrived to join them, and they continued to dig and plant for several weeks. Although in number they amounted to 30-40 people, they confidently predicted that they would soon be joined by 5000 more…

Based on their proclamations and Gerard Winstanley’s writings, the ethos of the group can be said to be a roughly egalitarian agrarian communism: they advocated the taking over of waste lands of the manors, by the poor, to be worked collectively, to grow food and raise animals, to feed all, for need, not profit.

The enclosure of common land – fencing off open fields, waste and woodland, for more intensive pasturing of sheep or more intensive agriculture, by landowners or their tenants – had become a major grievance in English rural society. Lords of the Manors, newer aspiring farmers seeking profits and speculators were enriching themselves by shutting out people who had traditionally used common land to graze animals, collect wood and other fuel, and gather foodstuffs. The loss of this access was catastrophic for many in rural communities, especially the poorest, for whom these customary rights formed a part of their precarious subsistence.

Revolt and protest against enclosure had been increasing for a hundred years, but social and economic change had strengthened the pressure to enclose and ‘improve’. The economic upheavals that contributed to and were then reinforced by the English Civil War laid even more pressure in the rural poor.

Hand in hand with desperation, the civil war was a product of, and also unleashed a further flood of, a spread of new rebellious ideas about religion, social order, and the rights or liberties of wider and wider sections of society. Everything came into question, as a broad alliance of religious non-conformists, rising classes seeking more power, and opponents of arbitrary royal rule rebelled against the monarchy. The floodgates opened, censorship collapsed, crowds began bringing radical politics into the streets as well as the print shops.

Opposition to the aristocratic and mercantile control of the land, fundamental to daily existence, was bound to come into question too. Royal lands previously enclosed but under parliamentary control were thrown open or raided by crowds for food. And as the civil war came to an end, the radical ideas that had emerged, often among the soldier-citizens of the New Model Army, found themselves expressed as ground-breaking thought and action on how land should be controlled, worked- and for whose benefit.

The group who took over St George’s Hill called themselves ‘True Levellers’, but we’re derogatively nick-named ‘Diggers’ – both names referencing both the current Leveller movement for political change, and previous social movements which had challenged enclosure of common land, in the ‘Midlands Revolt’ of 1607. Their adoption of the Leveller moniker upset the leadership of the Leveller group in London, who made it clear in several publications that they were not for the expropriation of anyone’s property, and not fully for the full emancipation of the social classes the ‘diggers’ were addressing and to some extent representing. In effect, that they weren’t up for ‘levelling’ at all… However, the Levellers we’re not united on the question of land; some of the agitator petitions had called for reversal of enclosures, and in other Leveller tracts more sympathetic mentions are made of opening up the commons. The pro-Leveller newspaper, the Moderate, printed the ‘True Levellers’ manifesto in full and uncritically. Later, after their political defeat by Cromwell, the Levellers were to stress resistance to enclosures more fully in their programs.

They may have chosen their local common and waste to dig on, but the site was perfectly placed to make the news and arouse both support and hostility. Close to London; close also to Windsor Great Forest, where hundreds of people had raided the king’s deer since the beginning of the civil war. Close to the routes from the capital to Portsmouth, where news travelled fast. Near to Kingston, a radical centre in religion and politics for several years before and after, with a long puritan tradition and a recent stronghold of the New Model Army in their fight against parliamentary moderates in 1647…

They may have chosen their local common and waste to dig on, but the site was perfectly placed to make the news and arouse both support and hostility. Close to London; close also to Windsor Great Forest, where hundreds of people had raided the king’s deer since the beginning of the civil war. Close to the routes from the capital to Portsmouth, where news travelled fast. Near to Kingston, a radical centre in religion and politics for several years before and after, with a long puritan tradition and a recent stronghold of the New Model Army in their fight against parliamentary moderates in 1647…

From the beginning of their project, however, thy encountered the violent opposition of some local residents. Over the first few weeks of the colony’s life, they were raided and attacked by mobs, sometimes numbering over 100, who burned houses they had built, stole and destroyed their tools, forcibly dragged some of the ‘diggers’ to Walton Church where they were assaulted and abused.

The local landowners, led by Francis Drake, lord of the Manor of Walton, John Platt, lord of the Manor of Cobham, and Sit Anthony Vincent, lord of the Manor of Stoke d’Abernon, co-ordinated attacks on the ‘diggers’.

News of the commune spread quickly: by April 14th, only two weeks after they had launched their experiment, the leaders of the Levellers in London issued a manifesto, in which, despite not mentioning the St George’s Hill events, saw them refuting any links to those who would ‘level all men’s estates’. Opponents of the Levellers were clearly seizing the chance of associating them with the communists in Surrey to attempt to scare people into backing off from supporting them. It shows the limit of the Leveller programme, and their organisational weakness at the time, that they feared the association and took steps to distance themselves from the ‘True Levellers’.

Later in April, one or more of the ‘diggers’ again invaded the church at Walton, filling the pulpit with briars and thorns to prevent the parson from preaching…

Despite the attacks, the St George’s Hill commune continued. Their activities had brought them to national prominence – on April 16th the group were discussed in the Council of State, after Henry Sanders of Walton informed the Council of their actions.

“On Sunday night last there was one Everard, once of the army but was cashiered, who termeth himself a prophet, one Stewer (Star) and Coulton and two more, all living in Cobham, came to St George’s Hill in Surrey and began to dig on that side of the hill next to Campe Close, and sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots and beans. On Monday following they were there again, being increased in their number and on the next day, being Tuesday, they fired the heath and burned at least 40 rood of heath, which is a very great prejudice to the Towne. On Friday last they came again, between twenty and thirty, and wrought all day at digging. They did then intend to have two or three ploughs at work, but they had not furnished themselves with seed-corn, which they did on Saturday at Kingston. They invite all to come and help them, and promise them meat, drink and clothes. They do threaten to pull down and level al park pales, and lay open, and intend to plant there very shortly. They give out they will be four or five thousand within ten days, and threaten the neighbouring people there, that they will make them all come to the hills and work; and forewarn them suffering their cattle to come near the plantation; if they do, they will cut their legs off. It is feared they have some design in hand.”

The Council (whose president, John Bradshaw, might have been thought biased – he owned the old manor house of Walton) wrote to General Fairfax, commander of the New Model Army, suggesting he took action against the group, on the grounds that

“although the pretence of their being there by them avowed may seeme very ridiculous yet that conflux of people may bee a beginning whence things of a greater and more dangerous consequence may grow to a disturbance of the peace and quiet of the commonwealth.”

Ie – this example might spread…

The Council also ordered the Justices of the Peace in Surrey

“… to send for the contrivers or promoters of those riotous meetings and to proceed against them…”

Two troops of mounted soldiers were ordered to Kingston, to investigate and put down any trouble. Their captain, Gladman, reported three days later to Fairfax that Gerard Winstanley and William Everard had agreed to come to London to explain their actions to the General. Gladman himself seems to have visited the commune at this time, and thought the Council was over-reacting.

On Friday 20th April, Everard and Winstanley appeared before Fairfax, refusing to remove their hats as assign they had no respect for social rank. Everard declared that since the Norman Conquest, England had lived under a tyranny more ruthless than the Israelites endured in captivity in Egypt; but that God had revealed to the poor that their deliverance was at hand, and that they would soon be free to enjoy the fruits of the Earth. Everard reported that he had had a vision, in which he had been commanded to “arise and dig and plant the earth and receive the fruits thereof.” The two men denied that they had any intention of seizing anyone else’s property and destroying enclosures, but were only claiming the commons, the rightful possessions of the poor. These they would work collectively, seeking to relieve the distressed. They did, however, give voice to their hope that the poor throughout the land would follow their example and take over common land, and named Hounslow, Hampstead Heath and Newmarket as places where they felt groups would shortly follow their lead. And though they refuted allegations that they were out to seize the lands of the wealthy, they did confidently assert that they believed soon that people would give up their property voluntarily, joining with them in community. Everard declared that they would not use force even in self-defence.

On the same day as this interview with Fairfax, April 20th, the group issued a manifesto, The True Levellers Standard Advanced, or the State of Community opened and presented to the Sons of Men.

The True Levellers’ ideas

The True Levellers Standard presents the True Levellers’ political and social program very much through what seem like a religious and mystical prism; as did many of the tracts and pamphlets of the civil war years. The Christian heritage of all the radicals was a common launching point; in the preaching and writings of the 1640s and 50s the texts of the bible are opened up to a flowering of a thousand interpretations, many of with them carrying subversive and ground-breaking thoughts…

The pamphlet takes the biblical idea of the Earth as God’s gift to all, equally, and turns it into social commentary, echoing John Ball in the Peasants Revolt, who had preached ‘When Adam delved and Eve Span, Who was then the gentleman?’ – God had intended no man to be lord over others. Greedy men had, by force and violence, set themselves up as lords over their fellows and over the earth.

The pamphlet takes the biblical idea of the Earth as God’s gift to all, equally, and turns it into social commentary, echoing John Ball in the Peasants Revolt, who had preached ‘When Adam delved and Eve Span, Who was then the gentleman?’ – God had intended no man to be lord over others. Greedy men had, by force and violence, set themselves up as lords over their fellows and over the earth.

“And hereupon, The Earth (which was made to be a Common Treasury of relief for all, both Beasts and Men) was hedged in to In-closures by the teachers and rulers, and the others were made Servants and Slaves: And that Earth that is within this Creation made a Common Store-house for all, is bought and sold, and kept in the hands of a few, whereby the great Creator is mightily dishonoured, as if he were a respector of persons, delighting int he comfortable Livelihoods of some, and rejoycing in the miserable povertie and straits of others. From the beginning it was not so.” (The True Levellers Standard Advanced)

Private property is described as the original sin: “For it is shewed us, That so long as we, That so long as we, or any other, doth own the Earth to be the peculier Interest of Lords and Landlords, and not common to others as well as them, we own the Curse, and holds the Creation under bondage; and so long as we or any other doth own Landlords and Tennants, for one to call the Land his, or another to hire it of him, or for one to give hire, and for another to work for hire; this is to dishonour the work of Creation; as if the righteous Creator should have respect to persons, and therefore made the Earth for some, and not for all: And so long as we, or any other maintain this Civil Propriety, we consent still to hold the Creation down under that bondage it groans under, and so we should hinder the work of Restoration, and sin against Light that is given into us, and so through fear of the flesh man, lose our peace.

And that this Civil Propriety is the Curse, is manifest thus, Those that Buy and Sell Land, and are landlords, have got it either by Oppression, or Murther, or Theft; and all landlords lives in the breach of the Seventh and Eighth Commandements, Thous shalt not steal, nor kill”

… while Christ and the early Christians had shared their goods and labour: ”It is shewed us, That all the Prophecies, Visions, and Revelations of Scriptures, of Prophets, and Apostles, concerning the calling of the Jews, the Restauration of Israel; and making of that People, the Inheritors of the whole Earth; doth all seat themselves in this Work of making the Earth a Common Treasury; as you may read… And when the Son of man, was gone from the Apostles, his Spirit descended upon the Apostles and Brethren, as they were waiting at Jerusalem; and Rich men sold their Possessions, and gave part to the Poor; and no man said, That ought that he possessed was his own, for they had all things Common, Act. 4.32”

But the time was coming when equal and free enjoyment of the earth would be restored, when the mastery of the landlords would be set down.

In seeing their actions on the commons as the beginning of that restoration of the earth as a Common Treasury, the ‘diggers’ also hail the Millennium – the impending return of Jesus, prophesied in the Book of Revelations, when earthly authority would be set down and a thousand-year rule of the saints begin. Almost all the civil war radicals thought the Millennium almost upon them; things began to get dangerous for the powers that be when, like the millenarians of the middle ages, the sects started to see themselves as the instruments who would bring the change about…

“But when once the Earth becomes a Common Treasury again, as it must, for all the Prophesies of Scriptures and Reason are Circled here in this Community, and mankind must have the Law of Righteousness once more writ in his heart, and all must be made of one heart, and one mind. Then this Enmity in all Lands will cease, for none shall dare to seek a Dominion over others, neither shall any dare to kill another, nor desire more of the Earth then another; for he that will rule over, imprison, oppresse, and kill his fellow Creatures, under what pretence soever, is a destroyer of the Creation, and an actor of the Curse, and walks contrary to the rule of righteousnesse: (Do, as you would have others do to you; and love your Enemies, not in words, but in actions).”

War and force developed, and continued to exist, only to defend private property:

“… wherefore is it that there is such Wars and rumours of Wars in the Nations of the Earth? and wherefore are men so mad to destroy one another? But only to uphold Civil propriety of Honor, Dominion and Riches one over another, which is the curse the Creation groans under, waiting for deliverance.”

In response to force, the True Levellers Standard Advanced firmly states the group’s position as one of passive resistance, of Pacifism and healing the divide with collective labour:

“And we shall not do this by force of Arms, we abhorre it, For that is the work of the Midianites, to kill one another; But by obeying the Lord of Hosts, who hath Revealed himself in us, and to us, by labouring the Earth in righteousness together, to eate our bread with the sweat of our brows, neither giving hire, nor taking hire, but working together, and eating together, as one man, or as one house of Israel restored from Bondage; and so by the power of Reason, the Law of righteousness in us, we endeavour to lift up the Creation from that bondage of Civil Propriety, which it groans under.”

Oppression is analysed as being not only down to some men raising themselves up to command others, but the rest accepting this, seeing themselves as unworthy and lesser… The rulers and the ruled both collude to allow the inequality to continue; in revolt against this, he asserts a social duty NOT to work for the rich: “This Declares likewise to all Laborers, or such as are called Poor people, that they shall not dare to work for Hire, for any Landlord, or for any that is lifted up above others; for by their labours, they have lifted up Tyrants and Tyranny; and by denying to labor for Hire, they shall pull them down again. He that works for another, either for Wages, or to pay him Rent, works unrighteously, and still lifts up the Curse; but they that are resolved to work and eat together, making the Earth a Common Treasury, doth joyn hands with Christ, to lift up the Creation from Bondage, and restores all things from the Curse.”

The ‘Standard’ strikingly references the sufferings of the civil war, the promises of liberty made by parliamentary leaders to enlist support from the common folk – promises broken:

“O thou Powers of England, though thou hast promised to make this People a Free People, yet thou hast so handled the matter, through thy self-seeking humour, That thou has wrapped us up more in bondage, and oppression lies heavier upon us; not only bringing thy fellow Creatures, the Commoners, to a morsel of Bread, but by confounding all sorts of people by thy Government, of doing and undoing.

First, Thou hast made the people to take a Covenant and Oaths to endeavour a Reformation, and to bring in Liberty every man in his place; and yet while a man is in pursuing of that Covenant, he is imprisoned and oppressed by thy Officers, Courts, and Justices, so called.

Thou hast made Ordinances to cast down Oppressing, Popish, Episcopal, Self-willed and Prerogative Laws; yet we see, That Self-wil and Prerogative power, is the great standing Law, that rules all in action, and others in words.

Thou hast made many promises and protestations to make the Land a Free Nation: And yet at this very day, the same people, to whom thou hast made such Protestatins of Liberty, are oppressed by thy Courts, Sizes, Sessions, by thy Justices and Clarks of the Peace, so called, Bayliffs, Committees, are imprisoned, and forced to spend that bread, that should save their lives from Famine.

And all this, Because they stand to maintain an universal Liberty and Freedom, which not only is our Birthright, which our Maker gave us, but which thou hast promised to restore unto us, from under the former oppressing Powers that are gone before, and which likewise we have bought with our Money, in Taxes, Free-quarter, and Bloud-shed; all which Sums thou hast received at our hands, and yet thou hast not given us our bargain…”

(It’s worth comparing this to the pressure for social change post World War 1 and WW2 – the narrative of collective suffering, the hardships gone through deserving a new social contract: ‘we haven’t gone through all of this for nothing’…)

The belief that the time of righteousness was almost upon them must have seemed justified. Momentous change was already afoot… only two months before, the king had been tried, executed and monarchy abolished. The struggle between the army leaders and rank and file soldiers & their political allies was coming to a head; mutinies we’re breaking out in the New Model Army. The sense of possibility, of boundaries being broken, of the social order of the world being turned upside down was electric.

General Fairfax thought the ‘True Levellers’ largely harmless, considering Everard slightly mad. Many others in power and influence were no so sure, as many of the newsbooks and papers of that month illustrate.

While some dismissed them as “a distracted crack-brained people” (A Perfect Summary of an Exact Diary of some passages of Parliament, April 16-23 1649), others feared their example would indeed lead others into following them. Mercurius Pragmaticus warned “What this fanaticall insurrection may grow into cannot be conceived for Mahomet had as small and despicable a beginning whose damnable infections have spread themselves many hundreds years since over the face of half the Universe.”

In the following week, a crowd drove the ‘diggers’ from St George’s Hill, but they soon returned and resumed their planting.

Around this time, William Everard left the group… Although Winstanley is much better known as leader of the’ Diggers’, because his writings expressed their ideas clearly and have survived. Everard was early on reckoned as the spokesman. Like the overwhelming majority of the radicals of the time, it seems likely that he had fought in the New Model Army – a man of that name appears as a scout in 1643 and another William Everard as an Agitator in 1647. Arrested after the mutiny at Corkbush Field, near Ware, in November 1647 (together with William Thompson, later shot attempting to travel to the Wellingborough digger commune, and other mutineers), he had been cashiered out of the Army. Thereafter he may have considered himself a prophet or preacher – if this is the same person as a man called Everard, staying with the radical John Pordage in Berkshire, in 1649, who later was ‘seen in London in a frantic posture’ and ‘committed by authority to Bridewell’. It may be the same man as the digger, who Fairfax in 1649 thought ‘a madman’.

Everard was later said to have left the St George’s Hill commune in April 1649 to join the mutiny against Cromwell at Burford, but this may be a confusion with a Robert Everard, who was present (and who also published radical pamphlets between 1649 and 1652); although William Thompson, arrested with Everard after Ware, was involved in the Burford events, leading some of the mutineers.

The thousands the True Levellers hoped would shortly follow their example, however, did not materialise. There were some expressions of solidarity. In May, A Declaration of the Wel-Afected in the County of Buckinghamshire (echoing some of their argument and language) asserted that the ‘middle sort’ of the County had been labouring under oppression, championed the ‘diggers’ and denounced anyone interfering with the “community in God’s way”. (An earlier tract from this county, A Light Shining in Buckinghamshire, had possibly influenced, and certainly chimed with, the ideas of Winstanley and his group.

Fairfax passed by St George’s Hill on May 29th, and met with the diggers again, and although he told them off, seems to have been satisfied they were pacifists posing no threat to order.

However, the local worthies of Walton and Cobham were surer about the threat to their private property, and again and again they led attacks on the little commune, repeatedly smashing houses, destroying plants and tools, and harassing and arresting diggers. In response, the diggers issued a second manifesto, written in late May, A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England, in which they announced they would cut and fell trees on the common to sustain themselves while they were waiting for crops to grow. The wood on the common belongs to the poor, they said, and they warned the lords to stop carrying off this wood.

In early June, the ‘Digger’ community was attacked by soldiers hired by the local landowners, commanded by a Captain Stravie, who wounded a man and a boy working on the land and burned a house. Two days later, four diggers were attacked on the common by several men, who beat them brutally, mortally injuring one. The thugs also smashed the diggers’ cart.

In July, an action was brought against the ‘diggers’ for trespass on the land owned by Francis Drake, and they were called to appear at Kingston Court. Indicted were Gerard Winstanley, Henry Barton, Thomas Star, William Everard, John Palmer, Jacob Hall, William Combes, Adam Knight, Thomas Edcer, Richard Goodgreene, Henry Bickerstaffe, Richard Mudley, William Boggeral and Edward Longhurst, all described as ‘labourers of Walton-on-Thames, and accused of ‘by force of arms at Cobham riotously and illicitly assembled themselves… to the disturbance of the public peace and that the aforesaid did dig up land to the loss of the Parish of Walton and its inhabitants.”

Their plea to be allowed to speak in their own defence (as they couldn’t afford, and on principle were opposed to, hiring a lawyer) was refused, and a hostile jury found them guilty. They were fined ten pounds per person for trespassing and a penny each for costs, but couldn’t pay this, and so two days later bailiffs raided the settlement and carried off some of their goods and four cows (though these were subsequently rescued by ‘strangers’. Henry Bickerstaffe was also imprisoned for three days.

At some point, John Platt of Cobham, one of their main opponents, pledged to join the group and bring in his property in common, if Winstanley could show to his satisfaction that justify their actions in scripture; however, this was either a trick or Platt was unconvinced, as his backing for attacks on the commune continued.

In August, Winstanley was arrested again for trespass, and fined four pounds. Bailiffs again unsuccessfully tried to drive off the diggers’ cattle, though they were pastured on a neighbour’s land. More attacks sponsored by the landowners took place – five diggers were assaulted, arrested and spent five weeks in prison. On November 27-28, a group of local men and soldiers were ordered by the lords of the manor to again destroy the houses the group had built and carry off their belongings. Not all the men carrying this out were happy to be the tools of the landlords – one soldier gave some money to the diggers.

Still the communists continued to return to St George’s Hill and replant crops of wheat and rye, and build little houses, declaring that only starvation could deter them from their mission of making “a common treasury” of the earth.

The church also entered the struggle against the True Levellers. Surrey ministers preached to their congregations that they should not give any food or lodgings to the communists; they were denounced as atheist, libertines, polygamists and ranters.

At some point, the St George’s Hill commune sent out a delegation to travel around and urge the poor in other areas to follow the group’s example and to collect financial aid for the beleaguered experiment. This delegation, consisting of at least two of the original group, travelled through Buckinghamshire, Surrey, Hertfordshire, Middlesex, Berkshire, Huntingdonshire and Northamptonshire, visiting more than thirty towns and villages, carrying a letter signed by Winstanley and twenty-five others, declaring that they would continue their struggle but appealing for funds, as their crops had been destroyed.

These ambassadors were arrested in Wellingborough in Northamptonshire; perhaps because here their message inspired a second digger revolt. In March 1650, poor inhabitants of the town began to dig collectively on a “common and waste-ground called Bareshank”. [a piece of land on the left-hand side of the road coming from Wellingborough (from the Park Farm Industrial Estate past the “Mad Mile”) at the junction where it meets the Sywell to Little Harrowden Road.] They managed to secure the support of several freeholders and local farmers, but faced similar repression as the Surrey commune.

On April 15, 1650, the Council of State ordered Mr Pentlow, a justice of the peace for Northamptonshire to proceed against ‘the Levellers in those parts’ and to have them tried at the next Quarter Session. Nine of the Wellingborough Diggers – Richard Smith, John Avery, Thomas Fardin, Richard Pendred, James Pitman, Roger Tuis, Joseph Hichcock, John Pye and Edward Turner – were arrested and imprisoned in Northampton jail and although no charges could be proved against them the justice refused to release them.

Captain William Thompson, a leader of the failed 1649 “Banbury mutiny” of Levellers (most of whom were killed in the churchyard whilst trying to escape) was apparently killed – in a skirmish on his way to join the Digger community in Wellingborough – by soldiers loyal to Oliver Cromwell in May 1649.

Another digger collective also started up at ‘Coxhall’ in Kent; the location of which is uncertain (it as been suggested it was northwest of Dover; or was Cox Heath near Linton, Cock Hill near Maidstone or even Coggeshall in Essex, the latter being a radical hotspot). Its worth noting that in 1653, a pamphlet was published in Kent, anonymously, called No Age like unto this Age, which according to Christopher Hill showed digger influence.

It’s though that the travelling delegation visited areas where the diggers had contacts or thought they would meet a sympathetic audience. There may well have been digger groups or attempted communes at Iver (the origin of the Light Shining in Buckinghamshire pamphlet), Barnet in Hertfordshire, Enfield in Middlesex, Dunstable (Bedfordshire), Bosworth (Leicestershire), and other unknown locations in Gloucestershire and Nottinghamshire. Many of these are listed as being visited by the digger ambassadors, as was Hounslow, where another colony was definitely planned. Hounslow Heath and Enfield Chase were regular venues for anti-enclosure struggles; it’s likely some of those resisting landlord encroachment onto common land were also involved in digger-like actions.

Enclosure battles at Enfield also inspired local resident William Covell to write a pamphlet, known under two alternative titles, A Declaration unto the Parliament, Council of State and Army, and The Method of a Commonwealth, suggesting a radical new approach to land use, which bore some resemblance to the diggers’ program.

It’s worth noting that both Covell and the Diggers did not take their starting point as the re-opening of enclosed common land with a resumption or preservation of common rights as then understood. Common rights as evolved under several centuries of tradition were a complex web of custom, class relations and toleration. Although they had been created by struggle between landowners and local residents, they were rarely simple. Rights could be bought and sold, and ‘commoners’ with defined interests in manorial waste or fields could be wealthy themselves, sharing some but not all interests of the poor whose access was a matter of tradition. Commoners in one manor could be enclosers or encroachers on the common there or elsewhere; some supported enclosure with promise of compensation; some opposed from their own point of view or from feelings of social conscience or desires to maintain social peace.

In contrast to this, Winstanley proposed common land be collectivised for need, by those in most need, and worked and controlled from below. In this can possibly be seen their class awareness that commoners and poor did not share the same interests. Rights of well-to-do commoners would go out of the window with the ‘rights’ of the lords of the manors. The common good would determine land use. This in itself was a threat not only to the landowners but the wealthier tenants and the church, and to many ‘commoners’ as well. It also may have unsettled some poorer residents who feared their own slender rights were under question: these last may have been easy to whip up against the diggers by the richer locals, ‘Look these people will take away the little you have!’ (say the ones already taking it away with the other hand…)

The communists moved from St. George’s Hill to nearby Cobham Heath early in 1650.

In February 1650, the Council of State again ordered army intervention, bidding Fairfax to address complaints of woods being ‘despoiled’ by arresting the offenders, to prevent the diggers encouraging “the looser and disordered sort of people to the greater boldness in other designs…”

By April 1650, the St George’s Hill commune was in effect defeated and the second experiment at Cobham also followed shortly. A week before Easter Parson Platt attacked a man and a woman working on the heath; a week later he returned with several men and set fire to houses and dug up the corn. Eleven acres of corn and a dozen houses were destroyed; a twenty four hour a day watch was put on Cobham heath to prevent any resumption of digging. The diggers were threatened with death if they returned. A ‘Humble Request to the ministers of both universities and to all lawyers in every Inns-a-Court’ complaining of Platt’s actions, but without result.

This marked the end of the active communist phase of the True Levellers, though Gerard Winstanley continued to write and set out radical egalitarian ideas.

Subsequent centuries

Land and access to it remained a central issue for English radicals. Enclosure gained pace, and agricultural improvement brought in new farming methods, displacing thousands from rural existence. The profits of enclosure partly funded the Industrial Revolution… all these factors led to a massive influx into cities and a transformation from a mostly rural to a mostly urban industrial society. But the grievance of dispossession remained a bitter memory, and a yearning to regain or take control of land remained part of radical traditions: giving birth to the ideas of Thomas Spence, among others, whose agrarian communism echoed Winstanley. Whether through emigration to more open societies where land was plentiful (eg the US), resettlement projects like the Chartist Land Plan, nationalisation movements such the Land and Labour League… the feeling that land ownership, land use and control was crucial to creating a more equitable society was at the heart of social programs.

But Winstanley’s and the True Levellers’ program remained revolutionary – most of the plans and proposals for use of land developed by radials in the hundreds of years following 1649 had nowhere like as ground-breaking implications. Their ideas for the sharing of land, both in use and in its produce, for need not for profit, are still revolutionary today.

In the last century, food production has become more and more divorced from urban life, as capitalism and mass production have altered how people farm, distribute and consume agricultural produce. Land ownership remains largely the province of the wealthy, much of UK open land and farmland is still in the hands of the aristocracy, though huge transnational corporations or utility companies and quangos also now won large stretches…

The True Levellers’ words remain as true as ever: “The common People are filled with good words from Pulpits and Councel Tables, but no good Deeds; For they wait and wait for good, and for deliverances, but none comes; While they wait for liberty, behold greater bondage comes insteed of it, and burdens, oppressions…”

We’re still hounded and bounded by “taskmasters, from Sessions, Lawyers, Bayliffs of Hundreds, Committees, Impropriators, Clerks of Peace, and Courts of Justice, so called, does whip the People by old Popish weather-beaten Laws, that were excommunicate long age by Covenants, Oaths, and Ordinances; but as yet are not cast out, but rather taken in again, to be standing pricks in our eys, and thorns in our side… Professors do rest upon the bare observation of Forms and Customs, and pretend to the Spirit, and yet persecutes, grudges, and hates the power of the Spirit; and as it was then, so it is now: All places stink with the abomination of Self-seeking Teachers and Rulers. For do not I see that everyone Preacheth for money, Counsels for money, and fights for money to maintain particular Interests? And none of these three, that pretend to give liberty to the Creation, do give liberty to the Creation; neither can they, for they are enemies to universal liberty; So that the earth stinks with their Hypocrisie, Covetousness, Envie, sottish Ignorance, and Pride.”

But as they wrote, our time is coming…

“Take notice, That England is not a Free People, till the Poor that have no Land, have a free allowance to dig and labour the Commons, and so live as Comfortably as the Landlords that live in their Inclosures. For the People have not laid out their Monies, and shed their Bloud, that their Landlords, the Norman power, should still have its liberty and freedom to rule in Tyranny in his Lords, landlords, Judges, Justices, Bayliffs, and State Servants; but that the Oppressed might be set Free, Prison doors opened, and the Poor peoples hearts comforted by an universal Consent of making the Earth a Common Treasury, that they may live together as one House of Israel, united in brotherly love into one Spirit; and having a comfortable livelihood in the Community of one Earth their Mother.”

Here’s a version of ‘The Diggers’ Song’ or ‘You Noble Diggers All’, words composed by Winstanley, sung by Chumbawamba.

1999 Commemoration

In 1999, 300 people, under the banner of campaign group The Land is Ours, re-occupied part of St George’s Hill as a commemoration of the 350th anniversary of the launch of the Diggers’ Commune…

More on this action here

And some film of the march/occupation

The Land Is Ours were attempting to kickstart a new movement to discuss land use and ownership and encourage action for social change on control of land… As well as the diggers re-occupation they carried out some other brilliant actions… check out The Land is Ours

Also worth getting in touch with:

The Land Justice Network, a non-hierarchical network of groups and individuals including academics, farmers, housing activists, architects, ramblers, coders, musicians, planners, artists, land workers and bird watchers.

We recognise that present land use and ownership are the result of policies and decisions that have little basis in social justice or in considerations of the common good.

We work together to raise awareness of land as a common issue underpinning many struggles and injustices, and to turn this awareness into action that will challenge and change the status quo.

We are committed to working together using all tools available – including policy writing, direct action, land occupation, running workshops and events, sharing our skills and creating beautiful and compelling videos, pamphlets, films, infographics, flyers, songs, art and zines.

Join us to build a diverse and inclusive modern day land reform movement!

Read more past tense writings on resistance to enclosures in the London area here

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

On 31st March 2019 (yesterday), a few of us visited the Diggers memorial stone in Weybridge, erected in 1999, and St Mary’s parish church in Walton on Thames, where the diggers proclaimed the abolition of ministers, magistrates, tithes and the Sabbath in April 1649… We were remembering 1649, but also in memory of Brendan Boal, a major mover in the 1999 Commemoration, who died in October 2018.

Theres some pix here from yesterday…

RIP Brendan. Cigars got smoked.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2014 London Rebel History Calendar – Check it out online

Leave a comment