Swamps, huge and inundate

St George’s Fields was a large open space lying between Southwark and Lambeth, lying between modern Newington Causeway/Borough High Street to the east, and Kennington Road/Baylis Road to the west. Of old it stretched as far as the village of Newington in the south (around modern Elephant & Castle), and as late as the mid-18th century as far north as modern Marshalsea Road, though the Fields shrank over time as building encroached on its edges.

Part of the land had once belonged to the wealthy and powerful Brandon family, the Dukes of Suffolk, who swapped it with king Henry VIII who at one point intended to create a new royal hunting park there. In 1550 the City acquired the manor and other lands adjacent. The City’s jurisdiction in Southwark now stretched across from the various borders with Lambeth and Bermondsey. These lands were paid for through the use of the endowments of the Bridge House Estates.

For centuries the Fields were wet and wild, part marsh, part watery meadows & pools, criss-crossed with dirt paths. It was low-lying land, not suitable for agriculture. Before parts of the Fields were drained in the early modern era, it often flooded in winter. When main roads were constructed, they were raised up and cambered so that the water drained off them. But carts and coaches were often driven across the open ground when opportunity offered, to avoid the payment of road tolls, churning up the mud; between the main roads there were only gravel footways. A writer in 1807 complained that it was impossible to walk there in the daytime without being above the ankles in wet and mud, while at night people were in danger of breaking their limbs by falling into ruts or over hillocks of rubbish.

Though not all of the Fields was in the legal sense common land, access was open and seemingly unregulated for many years. The Fields became a customary place both of recreation and of popular assemblies. Citizens took their walks there, some collected wildflowers from the meads. In the 18th century pony races were held and itinerant showmen set up stalls and attractions along the roadsides. When the country was at war, the fields were often used for drilling and musters of militia.

Close to the City, but excluded from the City’s jurisdiction, the Fields became a favourite gathering place for young apprentices on holidays; and later developed into a place of meetings and demos, a sanctuary of outcasts & a starting point for riots & rebellions. Southwark, the “rogues’ retreat”, home to dodgy elements of many hues, bordered on the Fields. It also became a place much favoured by open-air preachers, who were not allowed to hold forth in London.

The Fields are mentioned a couple of times in Shakespeare’s plays:

Falstaff. I am glad to see you, by my troth, Master Shallow.

Shallow. O, Sir John, do you remember since we lay all night in the windmill in St. George’s Fields?

Falstaff. No more of that, good master Shallow ; no more of that.

Shallow. Ha, it was a merry night.

Shakespeare, Second part of Henry IV., Act iii. Sc. II.

York. Then, Buckingham, I do dismiss my powers:—

Soldiers, I thank you all; disperse yourselves

Meet me to-morrow in St George’s Field.

Shakespeare, Second part of Henry VI., Act v. Sc. I.

The second quote suggesting the Fields were used for military purposes as early as the 1590s.

Anti-royalist mobs met here in the run-up to the English Civil War, & the fields were a constant rallying point for the dissenters & pro-leveller crowds of the English Revolution. In May 1640, a great public meeting of city apprentices, glovers & tanners of Bermondsey & Southwark, sailors & dockers laid off due to trade depression: marched off to nearby Lambeth Palace to attack the unpopular Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud.

On May 14th 1640, rioting crowds broke open the City prisons & tried to free oppositionist aldermen. They planned to attack the house of the Earl of Arundel, who is believed to have fortified his garden (on the south bank of river) with cannon pointed at St George’s Fields. (Arundel’s son, the Earl of Dorset, later ordered troops to fire on citizens of London demonstrating against bishops outside Parliament in November 1641.) John Archer, a glover of Southwark, was fitted up as ringleader of these tumults, tortured, then executed.

In December 1654 Thomas Tany, preacher, prophet, agitator and writer, labelled a Ranter, burned a bible (“because people say it is the word of God and it is not”) on the Fields, before crossing the Thames, marching to Parliament & banging on the door with his sword. Tany held that God was in everything and therefore man could not lose his Salvation, and that Religion was “a lie, a cheat, a deceit, for there is one truth and that is love.” He had been indicted for blasphemy in 1651, and his attack on Parliament landed him in the Gatehouse Prison. Either at this time of a few months later, he was reported as was living on the Fields in a tent.

According to Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, St George’s Fields were one of the places of refuge to which the poorer citizens retreated with such of their goods and chattels as they could save from the Great Fire of London. Hundreds driven out of the City camped out in the open space.

In the second half of the eighteenth century the Fields were the site of or launchpad for some of the most tumultuous upsurges of the capital’s disorderly crowds, sometimes referred to as the “London Mob’ (though in truth there was probably more than one ‘Mob’). In 1768, a ‘Wilkes & Liberty’ crowd supporting populist demagogue John Wilkes was rallying here, as Wilkes was then being held in the Kings Bench Prison, on the edge of the Fields.

A man dressed in red allegedly threw a stone at the magistrate, and Captain Murray and three grenadiers chased and shot publican’s son William Allen dead in a cowshed at the Horse Shoe Inn. This was supposed to be mistaken identity. Other demonstrators were also shot. Weeks of rioting followed this ‘Massacre of St George’s Fields’.

Most famously, on June 1780, a meeting of Lord George Gordon’s Protestant Association on St George’s Fields, followed by a protest march against the Catholic Relief Act, ended with around 60,000 ‘Good Protestants’ marching from here through the City and Westminster,

“each person wearing a blue cockade, they paraded with flags, chanting hymns and psalms and then were marshalled into divisions and were addressed by their President. At noon one section, preceded by a man bearing on his shoulder the enormous parchment roll, said to record 100,000 signatures, crossed the river by Westminster Bridge, while the remainder divided into two parties, one proceeding along Blackfriars Road and over Blackfriars Bridge, and the other by Borough Road and Borough High Street to London Bridge.”

At Parliament they were joined by huge crowds, who saw a chance for an all-out burnin’ and lootin’ session. The result was the most serious uprising against the powers that be London has ever seen – the Gordon Riots. What began as an anti-Catholic pogrom, rapidly overflowed its sectarian origins and several days of all out insurrection saw all the London prisons were stormed and thrown open, then destroyed – including the King’s Bench, located on the Fields – and attacks on the property of the wealthy and symbols of power.

In the aftermath of the riots, the Fields were used as an army camp to host the soldiers called in to overawe the mob and quell the rioting.

And on 29th June 1795, up to 100,000 people thronged the Fields for a London Corresponding Society (LCS) mass rally, despite threats by the authorities to arrest any speakers. Numbers may have been boosted by the baskets of biscuits distributed to the poor by the LCS earlier in the day! The proceedings started at 3 p.m. and closed at 8. John Gales Jones, a shabby genteel surgeon, was the chief speaker. Resolutions for manhood suffrage and annual parliaments and against war with the French were passed.

The whole area attracted unruly elements. On the only part of the fields to be enclosed before the formation of the roads, Moulton’s Close at the western corner (roughly covering the site of the Imperial War Museum and the Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park), at the beginning of the 17th century stood a few tumbledown cottages, which the tenant, Gilbert Kefford, was made to pull down as a condition of the renewal of his lease in 1606, since they harboured “lewde and dissolute persons.”

As late as the early 19th century squatters or travellers lived on the Fields.

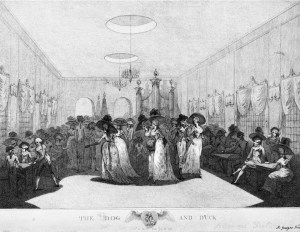

Local taverns were notorious. The Dog & Duck (located on the site of the tea gardens at Imperial War Museum) was a particular focus of local rowdiness. By 1695 the area was famous for its ‘medicinal waters’ and so a spa was set up. When this ceased to attract business it was abandoned but other entertainments were promoted, such as an organ and skittles. David Garrick, in his prologue to the 1774 play The Maid of the Oaks, alluded to the decline –

“St. George’s Fields, with taste of fashion struck,

Display Arcadia at the ‘Dog and Duck’;

And Drury misses here, in tawdry pride,

Are there ‘Pastoras’ by the fountain side;

To frowsy bowers they reel through midnight damps,

With Fawns half drunk, and Dryads breaking lamps.”

According to Edward Walford, the tavern gardens were used for popular concerts with an audience of “the riff-raff and scum of the town”, which became a public nuisance. The place gained a reputation for vice, being described as “a house in which gangs of both whores and rogues were constantly associated”.

Nightly entertainments of rope dancing, fireworks, tumblers attracted huge drunken crowds and trouble often centred on the Tavern.

Highwaymen would allegedly carouse at the Tavern before setting out to rob travellers. Francis Place reported that, as a boy, he had seen “two or three horses at the door of the Dog and Duck in St George’s Fields on a summer evening, and people waiting to see the Highwaymen mount … flashy women come out to take leave of the thieves at dusk and wish them success”.

The Dog & Duck’s infamy eventually led to its license being taken away in the late 18th century. In 1787, renewal of the licence was refused by the Surrey magistrates following a proclamation from George III against drunkenness. They decreed that “too many people assembled there of very loose character, and that it consequently became a receptacle for disorderly persons, and a place of assignation destructive of that morality which it was the duty of the law to see preserved”. However, the landlord applied to the City of London magistrates, who despite its being a house “so notorious as a resort for amusement and debauch”, granted a new licence on the ground that they had judicial rights over Southwark. This led to a legal dispute between the City and Surrey magistrates, which was decided in 1792 against the City magistrates. The licence of the Dog and Duck was made conditional on its being closed on Sundays. The tavern finally lost its licence completely in 1799.

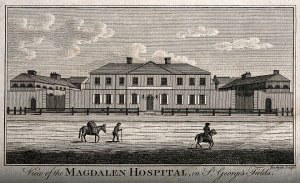

The open space, close to but outside the City boundaries, also lent itself to the building of centres of repression. The Kings Bench and Marshalsea Prisons stood on the Fields’s edges. In 1815 the City relocated Bethlehem Hospital (the original Bedlam), where the mad were chained and exhibited, to the site of the now defunct Dog and Duck.

The Fields was also the venue for the launching of the first British woman in flight (unless you count Anne Arthur): Letitia Ann Sage making her ascent on 29 June 1785, in a balloon launched by Vincenzo Lunardi (an Italian aeronaut).

On balance, this was an open space the powers that be probably wanted to be rid of.

However, the draining & development of St George’s Fields around 1810 came relatively late given its proximity to the profitable West End and City.

The earliest proposals for enclosure of the Fields came in 1698/99: the Bridge House Committee (representing the owners of much of the land) discussed with other property owners on the Fields the possibility of promoting a Bill in Parliament to enable them to enclose and consolidate their holdings. Nothing came of this project; a second agitation for enclosing the fields began in 1746 when Thomas Clarke, the main lessee of the Bridge House Estate, complained to the Committee about the inconveniences which he and other occupiers suffered because their lands lay open – notably because wagons were driven across the fields, to the ruin of the herbage, in order to avoid the turnpikes where weighing machines to assess tolls had recently been set up; also, during the recent “great murrain” of cattle, one infected beast driven on to the fields to graze had infected many others and caused a great many deaths. The report of the Surveyor to the Bridge House Committee endorsed Clarke’s statements, but the Committee took no positive action, except to put up notices in the fields prohibiting the driving of waggons and carts there. The project was allowed to drop for a time.

Before the Magdalen Hospital had been built near the Blackfriars Road in 1769 and the House of Correction in Hangman’s Acre in 1772, the County of Surrey obtained an Act from Parliament to extinguish the rights of common on these plots, since some locals claimed the right to graze their cattle there.

The Hedger family, proprietors of the Dog and Duck, had amassed a considerable fortune from the Tavern, and turned their eyes towards acquiring profitable land on St George’s Fields. They had been promised a lease of the Bridge House property in St. George’s Fields in 1776, but it was not until 1785 that a formal lease was signed. Between 1780 and 1800 they acquired an interest in a large part of the remainder of the fields on which they began to build houses.

By 1802 James Hedger had become known as the “King of St. George’s Fields”. He built on common land and the Court of Common Council took legal advice with a view to prosecuting him. The oldest inhabitants were called in to give evidence, and they stated that of old custom the gates were thrown open after Lammastide (1st August) and everyone who held property there was allowed to graze cattle freely – one horse or two cows for each acre held – and all the cattle turned in were marked by the pound keeper with the Bridge House Mark for a small fee. So common rights clearly existed… but the City’s counsel advised it would be difficult to make out a legal case for the enforcement of the custom against Hedger’s plans, since the Lammas Rights were originally intended to be solely for the benefit of those who held land in the fields, and Hedger now had the controlling interest there.

The Hedgers continued to build houses on the land. After 1785, other landholders of St. George’s Fields began to follow Hedger’s example in developing their land for profit. The most substantial houses, and the only ones of this period to survive, were those erected on the property of the West family in West Square, St. George’s Road and Temple Place, Blackfriars Road.

Hedger’s building activities on the main part of the fields did not go unchallenged. In 1800 one of his tenants, named Harkness, refused to pay his rent and broke down some of Hedger’s fences, on the ground that “the King of St. George’s Fields”, as he called Hedger, had no right to put them up. He was convicted and fined in the courts, but Hedger’s costs were so high that he lost more than Harkness did over the case.

The landlord, the City of London Corporation, decided that Hedger’s lease would not be renewed, as they were making larger plans for the “improvement” of the district. The development of the fields had so far been haphazard and lacking in amenities, and the quality of the houses was generally so bad that only the poorest tenants could be persuaded to live in them. The land around them was undrained. The buildings were, however, in such bad condition that it was obvious that they could not last very long, and the City Corporation refused to be responsible for repairs.

However, the City Corporation calculated that when the lease ended and they regained possession of the ground, they could replan the area almost from scratch, since there was every justification for pulling down the existing buildings.

1809 saw a Bill passed in Parliament, promoted by the Corporation in alliance with the neighbouring landowners, the Archbishop of Canterbury (who owned Lambeth Marsh), the Prince of Wales (who owned Prince’s Meadows), and the Surrey and Kent Sewer Commissioners, to secure a proper drainage system. James Hedger tried unsuccessfully to disrupt its passage, thinking his property might be adversely affected.

When the lease finally expired, Hedger started demolishing the buildings to reuse the materials elsewhere. The City officers tried to prevent the demolitions, but on the last day of the lease in March 1810, there was a riot in the fields, as several hundred people “of the lowest orders” gathered to join in the demolition and remove building materials. Hedger did not intervene because he was required to return the common land in its original condition and the looting was saving him clearance costs. Some houses were still occupied and the inhabitants lost their belongings and had to flee for their lives.

In 1810 the City Corporation obtained an Act of Parliament extinguishing all rights of common over St. George’s Fields and repealing a clause in an Act of 1786 which prohibited building within 50 feet of certain main roads there. Two years later a further Act enabled the City Corporation to sell off or exchange certain small pieces of ground in the fields. During the following 20 years all the Bridge House lands there were let on building lease, while the ground which did not belong to the Bridge House was also closely built up. In 1813 James Smith wrote—

“Saint George’s fields are fields no more;

The trowel supersedes the plough;

Swamps, huge and inundate of yore,

Are changed to civic villas now.”

Seven years later, however, the Bridge House Committee were still debating the best method of draining St. George’s Fields, and it was not until 1819 that general plans for doing so were agreed.

Within a few years, new developments were built up over St George’s Fields. One of the capital’s old playgrounds and rallying grounds was no more.

Leave a reply to mudlark121 Cancel reply