The Southwark Mint was one of London’s long-standing ‘sanctuaries’, areas in London whose inhabitants claimed certain rights and liberties, most notably to be free from being arrested for debt, as not all the usual writ of law was thought to apply there. The claimed ‘right of sanctuary’ against legal pursuit for debt was strongest from around the mid 1670s until the mid 1720s.

These areas had once technically come under another legal jurisdiction, generally either religious, or deriving from a charter granting some level of autonomous governance.

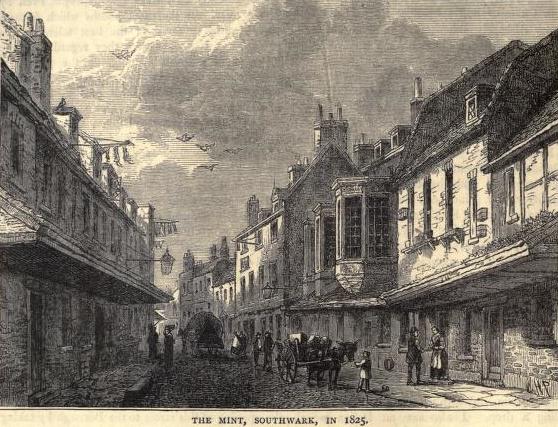

The area of the Mint covered the area of Suffolk Place & the area previously owned by the Brandon family, Earls of Suffolk, around Marshalsea Road & modern Mint Street (which was once much longer: it ran as far as Borough High Street where its entrance was called ‘Mint Gate’.)

The Southwark Minters claim to operate under another legal jurisdiction arose from a 1550 exemption from local jurisdiction when king Henry VIII set up a ‘mint’ at Brandon House to cast silver coinage, (supplementing the main Mint in the Tower of London). The area was then known as the Liberty of the Mint. Liberty indicating the exemption from City of London control. The actual Southwark Mint only operated for a short time: it closed after a year in 1551. But the area retained the name of the Mint despite its short existence. In the 1550s the area was handed over to the diocese of York and they leased it for development of housing, but this was generally cheaply built and of poor quality – the Mint rapidly became a slum. Over the next 300 years it grew to increasingly to be home mainly to the poor, overcrowded with garrets, courts, that teemed with some of London’s underclasses…

(supplementing the main Mint in the Tower of London). The area was then known as the Liberty of the Mint. Liberty indicating the exemption from City of London control. The actual Southwark Mint only operated for a short time: it closed after a year in 1551. But the area retained the name of the Mint despite its short existence. In the 1550s the area was handed over to the diocese of York and they leased it for development of housing, but this was generally cheaply built and of poor quality – the Mint rapidly became a slum. Over the next 300 years it grew to increasingly to be home mainly to the poor, overcrowded with garrets, courts, that teemed with some of London’s underclasses…

It was widely seen as a home to criminals, a breeding ground for immorality, theft, disorder, a refuge for ne’er-do-wells.

A condition of the Mint’s 1550 charter had turned this small area into a ‘Liberty’ outside the jurisdiction of the City Corporation, with residents afforded some protection from prosecution. The perception that living there gave some sanctuary against the normal run of law gradually led it to become a place of refuge, to some extent for robbers, rebels, deserters & malcontents, but mainly for debtors trying to evade imprisonment for debts they owed.

Imprisonment for debt was a constant threat for nearly everyone in eighteenth century London. Due to the scarcity of coin, many transactions had to be done on credit, making many folk into debtors of sorts, even if they were owed more than they were owing at any given time. Because claiming back debts this was a civil process, not a criminal one, everyone was at the mercy of their creditors, who had a powerful legal arsenal at their disposal. Debtors could be imprisoned before any hearing into the case was ever held. Release could only be obtained through settling the debt, even though imprisonment could mean earning the money necessary to do so was impossible. No determinate sentence was set, and time in jail did not work off any of the sum owed. Consequently, debtors could find themselves locked up for very long periods for trifling sums.

Many creditors resorted to the law, and many people suffered for it. The available figures suggest there were thousands of debtors incarcerated at any one time. Before the American revolution (temporarily) ended transportation to penal colonies as a sentence, the vast majority of the prison population were debtors. The prison reformer John Howard found 2437 so incarcerated in 1776; a pamphlet of 1781 listing all the debtors released by the Gordon Rioters when they stormed all of London’s prisons gave a similar number; government enquiries revealed 9030 locked up in 1817. To hold all these people there was a vast national network of gaols: nearly 200 across England and Wales in the eighteenth century, with 10 in London and Middlesex and 5 more in Southwark.

One way of avoiding prison was by taking refuge in the sanctuaries. There were eleven of these active in London and surrounds in the 1670s: on the north bank of the Thames in Farringdon Ward Without were Whitefriars, Ram Alley, Mitre Court, and Salisbury Court; on the north side of Fleet Street Fullers Rents; the Savoy off the Strand, the Minories by the Tower, Baldwin’s Gardens in Middlesex, and in Southwark Montague Close, The Clink and The Mint.

Each of these places claimed some sort of independent jurisdiction. In some case, such as Whitefriars, Montague Close and the Minories, there was a memory of religious sanctuary, although that right had been in fact abolished legally under king James I in the early seventeenth century. In other areas, there were charters allowing a level of autonomous governance, as with Whitefriars again, and the Clink in Southwark. The Savoy was owned by the Duchy of Lancaster. And with the Mint, there seemed to be both an administrative vacuum, and the ambiguity of being within the ‘Rules’ of the King’s Bench, an area outside that prison but where inmates were allowed to live.

What all these refuges had in common was a population of debtors prepared to physically defend these claims and take on the bailiffs that would arrest them.

Debtors holed up in the sanctuaries developed collective solidarity to resist bailiffs sent in to arrest any one of them, gathering together to prevent any arrests, often beating up the offending bailiff & kicking them out if the area. One tactic was to seize any bailiff, dunk them in successive water troughs then make them kiss a shit-covered brick and swear not to return.

(A tactic worth reviving for modern struggles… in a time of prepayment electric and gas meters imposed by force and increasing debt and CCJs…?!)

The collective solidarity of Mint inhabitants is described in William Harrison Ainsworth’s historical account of thief ‘& master prison breaker Jack Sheppard’ – Ainsworth labelled the area “The Grand Receptacle of Superfluous Villainry”: ‘Incursions were often made upon its territories, sometimes attended to with success but more frequently with discomfiture, and it rarely happened that any important capture could be carried be effected. In order to guard against accidents, or surprises, watchmen or scouts were stationed at the three main outlets of the sanctuary, ready to give the signal – ‘a blow on a horn’… bars were erected which in case of emergency could be stretched across the streets, doors were attached to the alley and were never opened except with due precautions; gates were affixed to the courts, wickets to the gates and bolts to the wickets. The back windows of houses were strongly barricaded … and furthermore, the fortress was defended by high walls and deep ditches in those quarters where it appeared most exposed. There was also a maze into which a debtor could run, the intricacies of which it was impossible for any Officer to follow him’.

An early account of such a fight, (in Poor Robin’s Intelligence, a two page broadsheet, written by the hack journalist Henry Care), described the ‘Amazons’ of The Mint repelling bailiffs in 1676:

Some 7.5% of Mint inhabitants who applied for relief from prison on the abolition of the sanctuary in 1723 were women. Although, under the doctrine of ‘Feme Covert’, married women’s property was seen as being their husbands’, and so they were not considered capable of having debts in their own name, single and widowed women WERE at risk of imprisonment, as much as men.

The collective solidarity in defence of neighbours threatened with arrest widened out to a general support for resistance to authority and willingness to get involved in rebellious and riotous crowd action… Nicking stuff, sometimes…

In May 1718, James Austin, inventor of Persian Ink powder, invited his customers to partake of an immense plum pudding weighing close on 1000lbs; but when the pudding was paraded through the streets near the Mint, a number of Minters stormed the procession, stole the feast, & took it back into the sanctuary to be devoured by all..

In April 1721, the Minters took up “Arms in defence of Liberty” & expelled press gangs from Southwark.Press gangs, forcibly impressing men into the navy, were a hated enemy of the London poor. Women often took the leading part in battles against them: especially prostitutes, many of who lived with sailors, the most vulnerable to navy press gangs.

Some posts on resistance to the press gang in London from this era

Calico rioters protesting cheap Imports of Indian cloth which were seen as a threat to the livelihoods of London silkweavers assembled in the Mint in 1719-20. Many weavers ended up in debt due the precarious nature of their trade, and weavers formed a substantial proportion of those seeking sanctuary. An article on this on the excellent Alsatia blog (from where much of this thread was shamelessly looted!)

Interestingly, it is suggested Minters generally took clearly different approaches to the application of law in the area where it did NOT relate to a pursuit for debt: a killer on the run might not be afforded solidarity and collective defence.

The collective defence of their ‘liberties’ led some to over-romanticise the condition of life in the Mint, possibly to be taken with a punch of salt, eg ‘Thomas Baston’s idea of the area as a semi-utopian ‘Little Republick”

Most of the sanctuaries were dissolved by statute in 1697; the Mint persisted a few decades longer.

In 1722-3, the Mint’s ambiguous legal status was specifically in special legislation. Any anomalous right of sanctuary, real or perceived, was specifically abolished in 1723.

In that year some residents of the Mint petitioned Parliament against this abolition of what they saw as ancient rights to sanctuary. An article on this petition on the Alsatia blog.

After the 1723 dissolution, nearly 6,000 Minters applied for relief and exemption from prison, giving an indication of the size of the debtor population there. Petitions and protests failed to persuade Parliament to renew a right to sanctuary from legal pursuit (unsurprisingly!)

Refugees from the Southwark Mint tried to set up a similar no-go area in Wapping for a short period, until suppressed by the army.

Civil imprisonment for debt was ostensibly abolished in 1869, but in reality was made ‘contempt of court’, a criminal offence. Coupled with the increasing financial demands of the state upon the population by way of taxes, imprisonment for debt continued unabated.

After the abolition of the sanctuary right, the Mint remained an area of extreme poverty into the late 19th century.

POSTSCRIPT: St Saviours Union Workhouse. In 1729 the parish of St. George the Martyr set up a ‘poor house’ in Mint Street. The new Workhouse Master was an expert in woolen goods and so the inmates were set to work producing saleable wool items. In 1782 the ‘poor house’ was replaced by a larger building with administration and public offices on the Mint Street frontage. It was built for 624 inmates with 14 infirmary wards and a vagrants section. Conditions were reported as appalling with neglect of every sort. In 1869 St. George’s became part of the St.Saviour’s Poor Law Union. The buildings continued in use until the 1920s. The site later became a depot for Southwark Council.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Much of this post is derived from the excellent work of @anterotesis on the great Alsatia blog

Leave a comment