“Thou art here indicted by the name of Flora, of the City of Rome, in the County of Babylon, for that thou, contrary to the peace of our Soveraign Lord, his Crown and Dignity, hast brought in a pack of practical Fanaticks, viz. Ignorants, Atheists, Papists, Drunkards, Swearers, Swash∣bucklers, Maid-marrions, Morrice-dancers, Maskers, Mummers, May pole-stealers, Health-drinkers, together with a rascalian rout of Fidlers, Fools, Fighters, Gamesters, Whoremasters, Lewd-men, Light-women, Contemners of Magistracy, affronters of Ministery, rebellious to Masters, disobedient to Parents, mis-spenders of time, abusers of the creature, &c.”

(Thomas Hall, Funebria Florae, Or the Downfall of the May Games, 1661).

It’s International Workers Day… (regardless of the British government’s attempt to deny the existence of class by shifting the Bank Holiday to next week).. so we hope you’re all taking the day off. Or pretending to work from home. Assuming you’ve not been laid off without pay from your zero hours gig.

Or are you being forced to jostle with workmates on a crowded site or in a care home, cause you won’t get paid if you don’t turn up? Jammed together in a flat with the kids? Trying to keep yourself safe while looking after the sick or dying, while your manager hides the PPE in case you “use too much”?

It’s May Day – a day to strike, skive, shirk and fight back, if you can… (and then let’s carry it on…)

But the lily-livered attempt to replace the Mayday holiday with a more nebulous and patriotic national holiday does remind us of the discomfort that May Day in its various forms has caused ruling elites over the centuries. There’s no better time than now to turn Mayday back into a threat again…

So for all of you workers, shirkers, dancers and chancers – here’s Neil Transpontine’s excellent romp through the history of Mayday in South London – from medieval games and cavorting with Satan (oh yes!), to mass strikes and riots in the City, it’s our holiday and we’re not giving it up.

This text was published as a Past Tense pamphlet in 2011. You can also download a PDF of the pamphlet

@@@@@@@@@@

May Day in South London: a history

Neil Transpontine

CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Ancient Festivals

3. The Merry Month of May – Middle Ages to Puritans

4. Milkmaids, Chimney Sweeps and the Jack-in-the-Green

5. Reinventing May Day

6. The Workers’ May Day: origins to 1930s

7. The Workers’ May Day After the Second World War

8. The Counter-Culture and the Folk Revival

9. Anti-Capitalist May Days

10. 21st Century May Day

10. Conclusion

11. Bibliography

1. INTRODUCTION

For centuries people have been celebrating the height of Spring, and the first signs of Summer, at the beginning of May. This text examines the diverse ways they have done so in London South of the Thames.

It is a story of milkmaids, chimney sweeps, kings, socialists, pagans, Christians, school children and anarchists. A story of maypoles, May Queens and Jack-in-the-Greens.

A story too of subversion and conflicts with the authorities: May Day has often been a focus of religious and political contention, and continues to be so down to the present day.

This text started out as a talk and has developed through participation in various May Day events in South London over the past few years. The first talk was given in 2003 to South London Radical History Group at the Use Your Loaf Social Centre in Deptford High Street. After further research, a revised talk was given in 2005 to South East London Folklore Society, then meeting at the Spanish Galleon in Greenwich.

Short versions of the talk were given at May Day events organised by the Strawberry Thieves Socialist Choir in Brockley at Toad’s Mouth Too (2004), Moonbow Jakes (2005), and the Brockley Social Club (2007). Then, in 2010, I gave a talk at the Deptford Arms as part of a lovely May Day folk evening organised by Kit and Cutter that also featured the singing of Martin Carthy.

In a sense then, this pamphlet has emerged out of the story it describes. I can only hope that it goes back into the stream to inform those who come after to celebrate the May.

2. ANCIENT FESTIVALS

Beltane

If we pick up one of the many books available on ‘Celtic spirituality’ or neopaganism we will find confident descriptions of the ancient festival of Beltane.

For instance according to Glennie Kindred (2001): ‘In the Celtic Pagan past, this was the night of the “greenwood marriage” where the union between the Horned God and the fertile Goddess was re-enacted by the men and women to ensure the fertility of the land. It was a night to spend in the woods, to make love under the trees, stay up all night and watch the sunrise, and bathe in the early morning dew. On this night, people walked the mazes and labyrinths and sat all night by the sacred wells and healing springs’.

This is though an imaginative reconstruction – in reality we know little about the precise content of religion and rituals in the British Isles before the Romans. We do though at least know that a festival has been held at this time of year for as long as records exist – although of course before the adoption of the Roman calendar the date ‘1st of May’ did itself not exist.

In his authoritative overview of seasonal customs, the historian Ronald Hutton (1996) notes that May Day is something of an exception to ‘the almost total absence of concrete evidence concerning pre-Christian seasonal rituals in the British Isles’. Early Medieval Irish documents refer to the burning of fires on Beltane or Beltine at the beginning of May, between which cattle were driven to protect them. A ninth-century document links this custom with the Druids (Hutton 1991).

Records of similar practices are found from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and South West England until into the nineteenth century. As well as fires, Beltane was associated in some areas with other customs, such as hanging rowan branches around doorways. It is common for writers to refer to Beltane as associated with a god ‘Bel’. There was a god called Belenus who was worshipped in what is now Austria, although there is no evidence of this deity ever being associated with Ireland or British Isles. Bel may just be derived from the Celtic preface meaning ‘bright’ or fortunate (Hutton 1996).

There are though no records of Beltane fires in the south of England. The custom was presumably tied up with a pastoral economy where animals were driven out to new pastures in the summer months. If the custom was observed in the London area it must have died out before written records came into being.

We can only speculate where in what is now South London Beltane or some other seasonal festival may have been observed at this time of year in prehistoric times. Remains of pre-Roman monuments and settlements have been found in various locations. Along the River Thames these include a burial mound by what is now London Bridge, and a wooden structure by the mouth of the River Effra in Vauxhall. There are surviving traces of Iron Age hillforts at the south end of Wimbledon Common and at Keston Mark in the London Borough of Bromley, on a hill above the spring that is the source of the River Ravensbourne (misleadingly, both sites are known as ‘Caesar’s Camp’).

Doubtless those who lived around these sites marked the turning of the seasons in their own way, but we do not really know how.

Floralia

The Romans celebrated the festival of Floralia from 28 April to 3 May in honour of Flora, the personification and goddess of flowers and greenery. Like later May Day festivities in the British Isles, it was sometimes associated with license and indecency – prostitutes apparently claimed the festival as their own. The festival included theatrical performances and public games, known as the Ludi Floralia.

There was a substantial Roman settlement in Southwark around the south end of London Bridge, and numerous other Roman sites south of the Thames, such as a temple in what is now Greenwich Park. It is quite probable that a Roman spring festival was celebrated in such areas during the centuries of Roman influence following the invasion of 43 CE, but as with the pre-Roman period there are no records to confirm this.

Flora remained an important image of the season, long after the organised worship of the Romans died out. An image of Flora can be seen to this day in Camberwell Road, with a codestone relief depicting a figure with a garland of flowers now embedded in the wall of a block of flats. This was originally displayed in Dr Lettsom’s mansion in Grove Hill, an 1809 description of which states that ‘The front is adorned with emblematical figures of Flora and the Seasons’ (cited in Walford, 1878). In the mid-19th century, there was also a Royal Flora Gardens in Camberwell, a pleasure garden in Wyndham Road.

3. THE MERRY MONTH OF MAY – MIDDLE AGES TO PURITANS

Maying

O the month of May, the merry month of May,

So frolic, so gay, and so green, so green, so green!

O, and then did I unto my true love say,

Sweet Peg, thou shalt be my Summer’s Queen.

(Thomas Dekker, 1600)

The Roman festival of Floralia was associated with the wearing of garlands of flowers, and this has remained a common feature of May Day celebrations through the ages. This is not surprising as the proliferation of flowers is such a feature of the natural season, as is the shift to a warmer climate more suitable for outdoor celebrations.

In early modern England, May Day was one point in an annual ‘calendar that drew on celestial, pagan and ecclesiastical elements’. In addition to ‘the natural calendar of the seasons’ there was an ‘agricultural rhythm of cultivation, harrowing, planting and harvest… further modified by the cycles of lambing and calving, droving and herding, and the autumn slaughter of animals’. Then there was the ‘ceremonial calendar of the Christian year’, marking the life of Christ and the saints (Cressy 1989).

By the Middle Ages the whole ‘merry month of May’ was associated with communal celebrations in England, particularly the holidays of May Day and Whitsun. Festivities included games, fairs and communal feasts (often known as ‘ales’), with music, dancing and sports. Hutton (1996) suggests that the weather was one of the reasons for this: ‘Commoners, unlike royalty and the aristocracy, lacked large buildings in which communal festivities could comfortably be held in bad weather’. The warmer weather in May enabled outdoor gatherings, and in addition ‘it lay conveniently between the heavy work of ploughing and sowing, and that of hay making’.

The custom of going out to collect flowers and greenery on May Day, sometimes known as ‘Maying’ or simply ‘The May’, is described in the London area for as long as written records exist and no doubt had its origins in an even earlier period. It did not die out until late in the nineteenth century, by which point urbanisation meant that many people would have had quite a journey to find flowering hawthorn or other suitable foliage.

In his Survey of London (1603), John Stow wrote that ‘in the month of May, the Citizens of London of all estates, lightly in every Parish, or sometimes two or three parishes joining together, had their several mayings, and did fetch in Maypoles, with diverse warlike shows, with good Archers, Morris dancers, and other devices for pastime all the day long, and towards the Evening they had stage plays, and Bonfires in the streets’; and that ‘on May day in the morning, every man, except impediment, would walk into the sweet meadows and green woods, there to rejoice their spirits with the beauty and savour of sweet flowers, and with the harmony of birds, praising God in their kind’ .

Henry Machyn, a London merchant, recorded in his diary in 1559 that ‘The first day of May’ was marked ‘with streamers, banners, and flags, and trumpets and drums and guns, going a Maying’ and at the Queen’s place at Westminster ‘they shot and threw eggs and oranges at each other’.

A more hostile account is given by Philip Stubbes in his The Anatomie of Abuses, first published on 1 May 1583: ‘Against May, Whitsunday, or other time, all the young men and maids, old men and wives, run gadding overnight to the woods, groves, hills, and mountains, where they spend all the night in pleasant pastimes; and in the morning they return, bring with them birch and branches of trees, to deck their assemblies withal. And no marvel; for there is a great lord present amongst them, as superintendant and lord over their pastimes and sports, namely Satan, Prince of Hell’.

Bringing in the May was sometimes accompanied by dancing, processions and other pleasures. Stubbes claimed that ‘of forty, threescore, or a hundred maids going to the wood overnight, there have scarcely the third part of them returned home again undefiled’ – although demographers have found no evidence of a 1 February baby boom nine months later.

One of the first references we have to May Day in South London comes from 1492 when King Henry VII is recorded as having paid ten shillings ‘to the maidens of Lambeth for a May’ – presumably a garland of flowers, perhaps accompanied with some kind of performance. The King’s interest seems to indicate that May Day customs were observed at all levels of society. This vignette also suggests another feature of May Day: as well as being a time of popular celebration, it was also an opportunity to earn some extra income. As we shall see, this was an important aspect down to the 19th century.

May kings and queens

A feature of the May festivities was sometimes the crowning of a mock-king. Once again, Stubbes (1583) provides the most colourful description of this: ‘the wild heads of the parish conventing together, chose themselves a grand captain (of mischief) whom they ennoble with the title of my Lord of Misrule… they have their hobby horses, dragons and other antiques, together with their bawdy pipes and thundering drummers, to strike up the Devil’s Dance withal, then march those heathen company towards the Church and churchyard, their pipers piping, drummers thundering, their stumps dancing, their bells jingling, their handkerchieves swinging above their heads like madmen, their hobby horses and other monsters skirmishing among the throng’.

The May King or Lord was sometimes accompanied by a female counterpart – an instance is recorded at Kingston – but frequently not. The prominence of the May Queen seems to have initially been a literary invention of early seventeenth century London-based poets such as Michael Drayton and William Brown. Hutton (1996) remarks of these urban pastoralists that ‘their difference in priorities from genuine rustics is shown in their constant descriptions of pretty May Queens in preference to the more common village lords’.

Robin Hood

Robin Hood and his entourage were also sometimes associated with May festivities. Kingston in Surrey was known in the 16th century for its Robin Hood plays held over five days in May, featuring all the usual characters of Little John, Friar Tuck and Maid Marian, the latter usually played by a man in drag.

On May Day 1515, Henry VIII and the Queen ‘rode a Maying from Greenwich to the high ground of Shooters hill, where as they passed by the way, they spied a company of tall yeomen clothed all in Green’. The staged pageant included ‘Robin Hoode’ leading a band of 200 archers. ‘Robin Hoode desired the King & Queene with their retinue to enter the greene wood, where, in harbours made of boughs, and decked with flowers, they were set and served plentifully with venison and wine, by Robin Hoode and his men, to their great contentment, and had other Pageants and pastimes’ (Stow, 1603). The company included Lady May, Little John, Friar Tuck and Maid Marian.

Another account of this event is given by Sebastian Giustinian, a Venetian ambassador to the court of Henry VIII at the time. The Venetian party had arrived in London shortly before, travelling by road from Dover to Deptford where they were met on 16th April by fifty of the King’s horseman to accompany them into London. On the first day of May 1515 ‘his Majesty sent two English lords to the ambassadors, who were taken by them to a place called Greenwich, five miles hence, where the king was, for the purpose of celebrating May Day. On the ambassadors arriving there, they mounted on horse-back, with many of the chief nobles of the kingdom, and accompanied the most Serene Queen into the country, to meet the King. Her Majesty was most excellently attired, and very richly, and with her were twenty-five damsels, mounted on white palfreys, with housings of the same fashion, most beautifully embroidered in gold, and these damsels had all dresses slashed with gold lama in very costly trim, with a number of footmen in most excellent order’.

The party then proceeded to Shooters Hill: ‘The Queen went thus with her retinue a distance of two miles out of Greenwich, into a wood, where they found the King with his guard, all clad in a livery of green, with bows in their hands, and about a hundred noblemen on horseback, all gorgeously arrayed. In this wood were certain bowers filled purposely with singing birds, which carolled most sweetly, and in one of these bastions or bowers, were some triumphal cars, on which were singers and musicians, who played on an organ and lute and flutes for a good while, during a banquet which was served in this place; then proceeding homewards, certain tall paste-board giants being placed on cars, and surrounded by his Majesty’s guard, were conducted with the greatest order to Greenwich, the musicians singing the whole way, and sounding the trumpets and other instruments, so that, by my faith, it was an extremely fine triumph, and very pompous, and the King in person brought up the rear in as great state as possible, being followed by the Queen, with such a crowd on foot, as to exceed, I think, 25,000 persons’. After Mass and more feasting at Greenwich, the day finished with the King taking part in a jousting tournament.

May Day seems to have been celebrated regularly by Henry VIII at Greenwich as the start of the summer season. In 1536, his then Queen Anne Boleyn sat with him in the royal box to watch the May Day jousting. It was to be her last public appearance – the following day she was arrested, and on May 19th she was beheaded.

The daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, Queen Elizabeth the 1st, was also an enthusiast for May games. Machyn records that on the 25th June 1559 there was a special performance for her at Greenwich of ‘a May game’ featuring a giant, St George and the Dragon, Morris dancing, Robin Hood, Little John , Maid Marian, Friar Tuck, and the Nine Worthies of Christendom.

These Elizabethan May games were evidently very lavish. For the 1559 games, the City of London’s Ironmongers company sent ‘men in armour to the May game that went before the queen’s majestie to Greenwich’ and in 1571 ‘the Merchant Taylors sent 187 men in military costume, as their proportion towards a splendid Maying’ (Timbs, 1866).

Queen Elizabeth is also linked with another South London May Day. On 1 May 1602, ‘the Queen went a-maying to Mr. Richard Buckley’s at Lewisham’ (Lyson, 1796). Local legend has it that this occurred by an oak tree on what is now One Tree Hill, and that as a result this tree became known as the Oak of Honor – giving its name to the surrounding area of Honor Oak.

Maypoles

In the political and religious conflicts that shook England in the 16th and 17th century, popular festivities were often a focus of controversy. As the most visible symbol of May Day, it was the maypole itself that was frequently targeted. Philip Stubbes (1583) was typical of the Puritan reformers who regarded it as a kind of pagan idol: ‘But the chiefest jewel they bring from thence is their Maypole, which they bring home with great veneration… Then fall they to dance about it, like as the heathen people did at the dedication of the Idols, whereof this is a perfect pattern, or rather the thing itself’.

Under Edward’s Protestant regime of the 1540s many seasonal festivities withered in the face of official hostility: in 1549 the Corporation of London even instructed property owners to prevent their servants from attending May games (Hutton 1994). It was in this climate that the local maypole in Wandsworth was sold off in 1547/8. It must have been replaced, because a century later it was destroyed once more, being dug up in 1640-1 shortly after the Long Parliament had dispensed the King’s ‘Book of Sports’ which had given some protection to popular festivities against the puritan onslaught. In 1644, Parliament passed an ordinance banning maypoles which were described as ‘a Heathenish vanity, generally abused to superstition and wickedness’.

In Bermondsey, there was a maypole at Horsleydown. A painting by Joris Hoefnagel of a fete there in around 1590 shows a very tall wooden pillar opposite the Tower of London, approximately where Potters Hill Fields park is now situated. Opposition to the local maypole was led by Edward Elton (c. 1569-1624), the vicar of St Mary Magdelen. Elton was a prolific puritan, the author of such works as ‘The complaint of a sanctified sinner answered’ and ‘A plaine and easie exposition upon the Lords prayer in questions and answers’. In 1617, after preaching against the pagan evils of May Day, Elton led a mob to cut down the local maypole.

A contemporary account records: ‘Some of these practitioners, with friends of the Artillery Garden, intended sport, but Parson Elton would not have it so, and desired the constable to strike out the heads of their drums, and he preached against it many Sabbath days. Further Elton and his people assaulted the said Maypole, and did, with hatchets, saws, or otherwise, cut down the same, divided it into several pieces, and carried it into Elton’s yard’ (cited in Clarke, 1902).

Another 17th century South London maypole is shown on a 1681 map near to the present Elephant and Castle junction, set up in the middle of the ‘King’s Highway to Southwark’, (now Newington Causeway)’. The fate of this maypole is unknown.

Repression and rebellion

The chopping down of maypoles can be seen as part of a broader assault of popular celebrations. According to Ronald Hutton (1994): ‘All over western and central Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries reformers attacked popular festivity and tried to enforce a stricter standard of sexual morality and of personal decorum… Vagrants, fornicators, and suspected witches were all persecuted with a new intensity, and formal entertainments tended to replace spontaneous and participatory celebration’.

For the radical historian Peter Linebaugh (1999), May Day ‘was always a celebration of all that is free and life-giving in the world. That is the Green side of the story. Whatever else it was, it was not a time to work. Therefore, it was attacked by the authorities… In England the attacks on May Day were a necessary part of the wearisome, unending attempt to establish industrial work discipline’.

But the picture is more complicated than a straightforward desire to suppress all festivities: ‘Maypoles and May games provided easy targets for reformers of manners… But a vigorous tradition of May revels survived the Reformation and withstood the hostility of puritan critics. May games, May bowers, May fairs and maypoles enjoyed a popular vigour, sometimes encouraged and at other times frowned upon by local authorities… The royal orders of 1617 and 1633, known as the Book of Sports, authorized “May Games, Whitsun Ales, Morris Dances and the setting up of Maypoles”‘ (Cressy, 1989).

It may be true that in the Cromwell period there was less official tolerance of May Day customs, and that after the restoration of the monarchy following the English Civil War there was something of an officially-sponsored return of popular revelry – in 1661 a 134 foot maypole was erected in the Strand ‘to replace the one removed in 1644’ (Hutton, 1994).

It would be simplifying matters though to say that 17th century Royalists were always more inclined to festivities than Parliamentarian Puritans, or that in the previous century Catholics were always more tolerant of them than Protestants.

Under the Catholic reign of Mary Tudor the Privy Council banned May games in Kent because ‘lewd practises… are appointed to begun at such assemblies’, while in the seventeenth century Deptford Royalist John Evelyn condemned May customs – although to be fair a major concern for him as a tree enthusiast was that people were cutting down ‘fine straight trees’ to be used for maypoles. Evelyn denounced ‘those riotous assemblies of idle people, who under pretence of going a Maying, (as they term it) do oftentimes cut down and carry away fine straight trees, to set up before some ale-house, or revelling place, where they keep their drunken Bacchanalia… I think it were better to be quite abolish’d amongst us, for many reasons, besides that of occasioning so much waste and spoil as we find is done to trees at that season, under this wanton pretence, by breaking, mangling, and tearing down of branches, and entire arms of trees, to adorn their wooden idol’ (Evelyn, 1662)

[Editor’s note: One swivel-eyed parson set out his objections to the May Games, listing some of the dodgy types it attracted: “a pack of practical Fanaticks, viz. Ignorants, Atheists, Papists, Drunkards, Swearers, Swash∣bucklers, Maid-marrions, Morrice-dancers, Maskers, Mummers, May pole-stealers, Health-drinkers, together with a rascalian rout of Fidlers, Fools, Fighters, Gamesters, Whoremasters, Lewd-men, Light-women, Contemners of Magistracy, affronters of Ministery, rebellious to Masters, disobedient to Parents, mis-spenders of time, abusers of the creature, &c.”

(Thomas Hall, Funebria Florae, Or the Downfall of the May Games, 1661). If you’re not in that list – get misbehavin’…]

Many Protestants were happy to celebrate a calendar of holy days and Saints days, with May 1st being marked as the feast day of the apostles Saint Philip and Saint James. Not all were averse to people enjoying themselves, for some the issue was rather that the secular celebrations should be kept completely separate from the sphere of the church.

What united rulers of whatever stripe, Royalist or Parliamentarian, was ‘the fear of riot and rebellion during a period characterised not only by dramatic religious change but by inflation and harvest failure’ (Hutton,1994). May was a prime month for such rebellion: the Peasants Revolt 1381 and Jack Cade’s rebellion 1450 both started during the May Whitsun holidays. In 1517 the events known as ‘Evil May Day’ took place in London, an uprising of apprentices that targeted the houses of foreigners living in the city – arguably an early ‘race riot’ and a reminder that popular rebellions are not always propelled by emancipatory impulses.

In May 1640, there was a revolt of Southwark apprentices during the May holidays. The focus was the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, a key ally of Charles I who was to be executed as a Royalist a few years later in 1644.

John Evelyn recorded in his diary on April 27th ‘the Bishop of Canterbury’s palace at Lambeth being assaulted by a rude rabble from Southwark’.

Seemingly a few days later it was attacked again: ‘placards suddenly appeared throughout the City urging the apprentices to rise and free the land from the rule of the bishops. At a public meeting on St. George’s Fields, the City apprentices and the sailors and dockhands, now idle through lack of trade, joined up with the glovers, tanners, and brewery workers of Bermondsey and Southwark who were on holiday for the May Day celebrations to hunt “Laud, the fox”‘ (Browner, 1994).

On May 11th Laud himself recorded: ‘Monday night, at midnight, my house at Lambeth was beset with 500 persons of the rascal riotous multitude. I had notice, and strengthened the house as well as I could, and, God be blessed, I had no harm.’ A young rioter was condemned at Southwark soon after and hanged and quartered. The king issued a proclamation ‘for the repressing and punishing of the late Rebellious and Traiterous assemblies in Lambeth, Southwark, and other places adjoyning’. Laud’s fellow royalist the Earl of Clarendon wrote that ‘this infamous, scandalous, headless insurrection, quashed with the deserved death of that one varlet, was not thought to be contrived or fomented by any persons of quality’ (Walford, 1878).

In 1649 May 1st was again eventful. It was on this day that radical Leveller prisoners in the Tower of London, including Greenwich-born John Lilburne, published ‘An agreement of the free people of England’. On the same day the Scroop’s Horse regiment unanimously agreed not to obey Cromwell’s decision to send them to Ireland. At least five other regiments joined them and set up a Council of Agitators. Having mutinied at Salisbury, they joined with other mutinous regiments, until on May 14th they were surprised by Cromwell at Burford. Hundreds were captured and imprisoned in Burford church, and the next morning three were executed in sight of their comrades.

4. MILKMAIDS, CHIMNEY SWEEPS AND THE JACK IN THE GREEN

Milkmaids and Bunters

Whether due to repression, or simply changes in taste, May games in London seemed to have declined somewhat by the eighteenth century. May Day was though kept alive by specific occupations: in particular milkmaids. There are reports of Milk Maids in London celebrating May Day from the mid-17th century, and indeed there are images from the 14th century of milkmaids dancing and carrying flowers, although these cannot definitively be linked to May Day.

On May 1st 1667, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary ‘Thence to Westminster; in the way meeting many milk-maids with their garlands upon their pails, dancing with a fiddler before them’. Pepys also recorded another seasonal tradition of May dew being good for the complexion: ‘My wife away down with Jane and W.Hewer to Woolwich, in order to a little ayre and to lie there tomorrow, and so to gather May-dew tomorrow morning, which Mrs Tuner hath taught here is the only thing in the world to wash her face with; and I am contented with it’ (28 May 1667). In Tudor times, Queen Catherine of Aragon is also said to have gathered May dew in Greenwich Park (Timbs, 1866)

The milkmaids’ ‘garland’ consisted of (often borrowed) silver plate decorated with flowers and ribbons which they carried on their heads. Accompanied by musicians they would go dancing through the streets collecting donations. This custom was seemingly in decline by the time Hone’s Every-Day Book was published in 1826, with its lament that ‘In London thirty years ago, When pretty milkmaids went about, It was a goodly sight to see, Their May-day pageant all drawn out. Such scenes and sounds once blest my eye, And charm’d my ears; but all have vanish’d, On May-day now no garlands go, For milkmaids and their dance are banish’d’.

Milkmaids were associated with one of the longest surviving maypoles in London, to be found ‘near Kennington Green… the Maypole was in the field on the south side of the Workhouse Lane, and nearly opposite to the Black Prince public house. It remained til about the year 1795, and was much frequented, particularly by milk maids’ (Hone, 1826).

As well as the milkmaids there are also references in the 18th century to ‘bunters’ May Day – bunter being a term for a prostitute. According to Roy Judge (2000), ‘The Bunters were, in fact, a kind of parody of the Milkmaids’ custom, with their pewter in place of silver… giving a deliberately grotesque show as public entertainment’. A 1770 print purporting to depict this includes the verse ‘What Frolicks are here /So droll and so queer/ How joyful appeareth the day/ E’en Bunter and Bawd Unite to applaud /And celebrate first of the May’ (The Humours of May Day.).

The Jack in the Green

By the beginning of the 19th century, May Day was associated more and more with another occupational group – the Chimney Sweeps. Robert Southey commented that ‘The first days of May are the Saturnalia of these people, a wretched class of men, who exist in no other country than England’ (Southey, 1836).

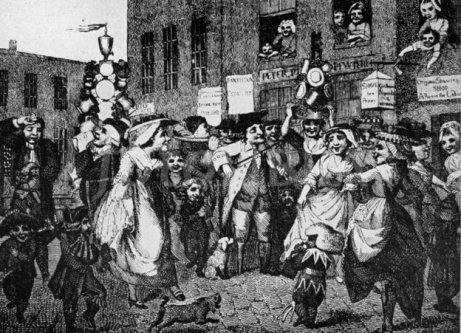

In his ‘Sports and pastimes of the people of England’ published in 1801, Joseph Strutt, described the Chimney Sweeps’ May Day: ‘The chimney-sweepers of London have also singled out the first of May for their festival; at which time they parade the streets in companies, disguised in various manners. Their dresses are usually decorated with gilt paper and other mock fineries; they have their shovels and brushes in their hands which they rattle one upon the other; and to this rough music they jump about in imitation of dancing. Some of the larger companies have a fiddler with them, and a Jack-in-the-Green, as well as a Lord and Lady of the May, who follow the minstrel with great stateliness, and dance as occasion requires. The Jack-in-the-Green is a piece of pageantry consisting of a hollow frame of wood or wicker work, made in the form of a sugarloaf, but open at the bottom, and sufficiently large and high to receive a man. The frame is covered with green leaves and bunches of flowers interwoven with each other, so that the man within may be completely concealed, who dances with his companions, and the populace are mightily pleased with the oddity of the moving pyramid’.

Another observer of this custom complained: ‘Unfortunately, the apparently innocent and somewhat child-like capers of the Jack-in-the-green and his jovial troop engender and increase the vice of drinking. At each halt, more refreshments are produced, and sobriety is not a distinctive quality of the poor in general, or of chimney-sweeps in particular’ (Thomson & Smith, 1877).

Henry Mayhew (1850) was told that costermongers (market traders) were also involved: ‘This kind of street performance is generally got up by some master sweep in reduced circumstances, who engages all the parties and finds the dresses. There was only one regular sweep in the school that my informant joined. Many of the Jacks-in-the-green are got up by costermongers. “My Lady” generally has 3s. a day, and is mostly the sweep’s or costermonger’s daughter or sister – anything, indeed, said my informant, so as she can shake a leg about a bit. The Clown gets 5s., the Jack 3s. or 4s., and the drum and pipes 6s. There are generally from five to six persons go out together, and the expenses (not including dresses) will be about 30s. a day, and the receipts about £3’.

The folklorist Roy Judge (among other things a Peckham teacher) wrote the classic study of ‘The Jack in the Green’ (2000). He rejects the notion that the Jack in the Green represents some kind of pagan survival from ancient times of a Green Man figure, noting that the first descriptions of a Jack in the Green on May Day date from the late 18th century. The pyramid of greenery may have evolved from the milkmaids garland which became increasingly more elaborate, with the structure carried on the head evolving into something that had to be carried by hand.

Within South London, reports of Jack in the Green have been found from Borough, Camberwell, Clapham, Greenwich, Tooting, Wandsworth and Lewisham where on May Day 1894 ‘a Jack with a Queen of May, two maidens proper, one man dressed as a woman, and a man with a piano-organ’ were spotted dancing and collecting money ‘In the High Street, at the inn near St Mary’s Church’ (cited in Judge, 2000).

The chimney sweeps’ May Day seems to have been in steady decline from the middle of the 19th century and had more or less disappeared by the end of the century. Acts of Parliament in 1842 and 1875 had prohibited the use of the child labour of ‘climbing boys’ whose presence was a source of sympathy and therefore charity on May Day. It is important not to be too carried away by the picturesque scenes of the Chimney Sweeps’ May Day – behind the Jack in the Green and the dancing there was acute poverty. May marked the end of the peak season for sweeps, making the search for extra income through ritualised begging a necessity. As William Blake wrote in his poem ‘The Chimney Sweeper’:

‘And because I am happy, & dance & sing,

They think they have done me no injury:

And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King

Who make up a heaven of our misery’.

The Jack in the Green survived a while longer. In around 1900 the Jack was spotted in Bermondsey: ‘Walking along Jamaica Road I saw what looked like a big bush hopping from one side of the road to the other, and bobbing up and down. This being the first time I had seen a Jack-in-the-Green it scared the life out of me’ (cited in Judge, 2000).

The Kentish Mercury reported on 18th May 1906: ‘It is not more than 3 or 4 years since such a band were seen in the streets of Deptford. Jack in his greenery, twirling, and the male and female dancers with him pirouetting something after the traditional style – but there was a sad falling off. In olden days the dancers used to be sweeps, to whom money collected was a sort of annual perquisite and sweeps were very jealous of their privileges in this direction being usurped, latterly however, this rule was by no means adhered to’. A photograph survives of the Deptford Jack in the Green on the back of which is a note from the photographer Thankful Sturdee, believed to have been written in about 1934, which reads: ‘Jack in the Green. Fowlers troop of Mayday revellers. ‘Jack in the Green’ was an old institution in Deptford and regularly kept up until about twenty years ago, when the police stopped all such customs’ (see Crofts, 2002).

One of the last descriptions we have is from St Thomas Street, SE1 from 1923 of ‘a man enclosed in an openwork cage of greenery dancing upon he road, accompanied by a girl in fancy dress, money being collected in a sieve’ (Judge, 2000)

Horse Parades

A final group of workers associated with May Day was those working with horses. May Day 1860, saw ‘the decorations of horses belonging to the several railway companies and other large establishments’ in South London. The annual procession from the South-Eastern Railway Company from the Bricklayers Arms on the Old Kent Road ‘created some sensation in the locality’ with the streets crowded and the horses ‘preceded by a band of music’. In the evening ‘a supper was provided for the drivers, presided over by the principal officials, at which about one hundred sat down’. However another custom had already faded away by this date: ‘The procession of mail-coaches which formerly drew such crowds to witness at the General Post-Office on May-day, no longer exists’ (South London Chronicle 5.5.1860).

An annual May Day parade of horses was held in this period at Wellington Wharf, Lambeth by Eastwood and Co. Ltd. The event had outgrown the Wharf by 1899 when it was moved to Battersea Park and featured nearly a hundred ‘gaily bedecked’ horse drawn vehicles. In the same year St Olaves Board of Works in Bermondsey agreed to give 5 shillings to each carman and dustman in its employ for the ‘parade of horses on May 1’ (South London Press, 6 May 1899).

Local Council workers also held a parade. In 1892 ‘the Bermondsey dustmen and other servants of the Vestry turned out with twenty-two teams’, and prizes were awarded to the most effective of them’ (The Graphic, 7 May 1892). May Day Cart Horse Parade, Bermondsey 1892

This event was still taking place at the turn of the 20th century: ‘On Tuesday the annual May Day parade of the horses belonging to the vestry of Bermondsey was held. Twenty four horses, with their carmen, paraded in Spa Road… at the conclusion of the judging, the parade was continued through the streets of Bermondsey until 1:30 pm, the carmen being given the remainder of the day as holiday’. Prizes were awarded for the best cared for animal (SLP, 5 May 1900).

In 1920, May Day horse parades were put on in Lee by employees of Mr. A. Manchester, horse and steam contractors (based at Dacre-Park) and at the Whitbreads bottling store in Lewisham, the latter a revival of ‘a popular feature before the war’ (KM, 7.5.1920).

5. REINVENTING MAY DAY

Much of what came in the 20th century to be understood as traditional May Day custom actually only dates back to the 19th century. The rise of industry and urbanisation fostered a dream of a return to a pastoral idyll, as seen for instance in the popularity of Arthurian romances and the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites. May Day was one of the arenas where this dream was manifested, and Hutton (1996) suggests that it was ‘substantially recreated by the Victorians’ prompted by ‘acute anxiety about the weakening of traditional social bonds’ and ‘a hankering after an idealized past, characterised by order and harmony’. Likewise Judge (2000) sees ‘The nineteenth century Arcadian view of May Day’ as rooted in the fact that ‘the problems presented by the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars and of the Industrial Revolution were enough to make a dream of rural innocence and peaceful tranquillity most attractive’. Still, as we shall see, this dream could be put to use for revolutionary ends as well as conservative ones.

While there were still some surviving May Day customs in the 19th century, more influential in the Victorian recreation of the festival were accounts of Tudor celebrations and romantic imaginings such as Tennyson’s ‘The May Queen’ (1830). Interestingly the May Queen, a seemingly marginal figure in the Middle Ages, came to be the centre of the Victorian May Day. And while in previous generations May Day had been celebrated by adults, the Victorians and Edwardians increasingly organised it as a children’s festival.

May Queens

One of the longest established modern May Queen customs in South London seems to have been in Walworth in Southwark, and actually pre-dates the Victorian period. According to the South London Observer, the first May Queen ceremony there took place at the York Street Independent Chapel in 1798 ‘when Walworth really was a village’ (SLO 6 May 1949). The ceremony was still being held in the same location 170 years later – now renamed the Browning Hall in Browning Street in honour of the poet Robert Browning who was baptised at York Street Chapel. A report from 1967 claims that it had been uninterrupted ‘with the exception of 1940’ (SLO 11 May 1967). The May Queen was presented with an emblem ‘enscribed with the names of previous queens’ (SLO, 5 May 1950).

The format was for children to nominate their own ‘Queen of the May’, who was crowned by her predecessor at a pageant also featuring maids of honour, page boys and heralds. Newsreel film of the 1920 May Queen ceremony in Walworth shows the May Queen being crowned at seven o’clock in the morning. The Queen and all her attendants wear white dresses, and all have foliage in their hair as well sashes of greenery over their shoulders. Several of them are also carrying branches. After the coronation they make their way on a pony and cart for the procession, with Girl Guides at the front and Scouts behind (British Pathe Newsreel 3 May 1920: There is also British Pathe newsreel film of the Walworth May Queen from 1927, 1928 and 1929.). In the 1920s at least, the May Queen and her maids of honour were treated to a trip to the seaside – in 1926 they were taken to Littlehampton for a weekend (SLP, 14 May 1926).

These features – white clothes, election by peers, crowning by the previous year’s Queen, a supporting cast of assistants – recur repeatedly in descriptions of various children’s May Queens from the 19th century down to the present.

Another well-established May Queen festival, and indeed one that has continued into the 21st century, is the London-wide event held on Hayes Common in the London Borough of Bromley. The first Bromley and Hayes May Queen Festival was held in 1907. In 1910, it featured a procession with a ‘Jack in the Green’ and the May Queen’s carriage, which made its way from the public gardens next to Bromley’s Free Library to Hayes where there was singing and dancing round the maypole. The event was organised by Joseph Deedy of 62 Bromley Common (Bromley Record, June 1910). In the following year, Deedy founded the Merrie England Society to encourage May queen ceremonies, especially in the London area. It established a London-wide May Queen festival at Hayes Common where by 1930 hundreds of schools were taking part ‘and little girls brought along May-dolls, of the nineteenth century sort, in prams’ (Hutton, 1996).

Becoming London May Queen was seen as a major honour. When Betty Wadsworth (aged 11) from Deptford High Street was crowned London May Queen in 1930, a reception was held at New Cross Cinema with the Mayor of Deptford in attendance. Betty’s father was an international footballer who was playing for Millwall at the time (SLP, 9 May 1930). The event sometimes received national coverage: in 1921, the winner of the Daily Mirror‘s children’s beauty competition was crowned London’s May Queen at Hayes (British Pathe newsreel 12 May 1921).

Often the May Queen was just one element in a wider May Day pageant. We have a detailed description of one such ‘May Day Festival’ put on by Bermondsey Settlement Guild of Play at Bermondsey Village Hall in 1898: ‘The children were all very prettily attired as merry maids, foresters, villagers, morris players, milkmaids, and shepherdesses. A real May tree in full blossom and quantities of freshly plucked flowers… were used in decorating the middle of the hall, the maypole being crowned with flowers and banked up with them at the bottom. A rustic throne covered with evergreens was provided for the May Queen’. There was dancing round the Maypole ‘to music of the time of Charles II’ and singing of old English songs. The May Queen was ‘a cripple girl who had been elected by the members of the Guild of the Brave Poor Things’ (The Times 2 May 1898).

An account of the same event two years previously suggested that the urban dwellers of this part of London could have no conception of the rural delights which May Day was intended to celebrate: ‘the fact that Bermondsey could boast a May Queen at all is distinctly creditable to the authorities of the Bermondsey Settlement, who are responsible for this pleasing and picturesque revival. It would have been better still, of course, if the affair had been the spontaneous outburst of a popular yearning for that faint and far away past when there were still green fields and spring flowers round Bermondsey Spa, vanished utterly long ago, save for the name of Spa Road. But there is not, probably, much spontaneous yearning after Arcady on the part of the latter-day population of that delectable region, and so one must, perforce, be content with what can be done by the organising efforts of those who devote themselves to the noble work of bringing all the sunshine and springtime that they can into the sombre existence of our London poor. How, indeed, can the Bermondsey Board School boy or girl know anything of the glories of Nature’s great Renaissance as it is going on far away from the smoke and smother of ignoble London’ (The Graphic, 2 May 1896).

These May events were often self-consciously nostalgic. In 1920 ‘The Childer Chaine’, a young people’s organisation linked to the Belgrave Hospital for Children in Clapham Road, held a ‘May Fair and Sale’ in at St John the Divine Parochial Hall in Frederick Crescent (Camberwell). The South London Press reported that ‘The hall was most effectively transformed into an Old English Village… The many stalls were constructed as representative of the “Good Old Days” and the stallholders and workers were attired in costumes of the period’.

The event included ‘a maypole dance by children of St George’s School, Camberwell, a Jack-in-the-Green procession, dances by members of the English Folk Dance Society’ and ‘a mummer’s play, “St George and the Dragon”‘ (SLP 14 May 1920).

All kinds of organisations seem to have been involved in organising such events through the first half of the twentieth century, including churches of all denominations. Bermondsey Settlement was initiated by a Methodist preacher; the temperance Band of Hope held a May Day concert with a May Queen at Robert Street Chapel, Plumstead in 1907 (Woolwich Pioneer 3 May 1907); and in 1950 the Roman Catholic Our Lady of Seven Dolours, Friary Road (Peckham) hosted festivities with a May Queen elected by St Francis Infants School and ‘wearing a white silk confirmation gown with blue trim’. The Guide movement was also active; in 1948 for instance, Peckham Rye Guides and Brownies elected the May Queen for the May Day Revels held at St. Antholin’s Church Hall in Nunhead.

In Stockwell, the local Church of England vicar was the driving force: ‘at St Andrew’s National School, Stockwell Green…. the girls give a very charming display on May Day… The girl who is chosen Queen for her good conduct is the heroine of the day… After a pretty dance round the Maypole, the pageant concludes by the Queen’s receiving homage from the other girls. The revival is due to the Rev. J.H. Browne, the vicar of St Andrews’ (The Graphic, 7 May 1898).

Schools were clearly also a focus. In 1908, ‘The seventh annual May day Festival was held at Choumert road Girls School’ in Peckham, where eight year old Edith Hollands was crowned Queen and there was a ‘rustic romp round the maypole’ (SLO, 6 May 1908). A Downham May Queen was crowned at Pendragon Junior Girls School ‘attended by heralds, train-bearers and a crownbearer’ (KM, 1 July 1938: For other examples see Kennington Road Girls School, SLO 8 May 1908; St Chrysostum Girls Club, Peckham, SLO 10 May 1946.)

Other events were organised by socialist and co-operative movements. In the early part of the 20th century, the Woolwich Children’s Co-operative Guild held an annual May Day festival. In 1905 it took place at the Co-operative Hall, Parson’s Hill: ‘In olden times such gatherings were wont to be held on the village green: for Woolwich in the twentieth century the green had to be the Cooperative Hall, with a brilliantly be-ribboned and be-flagged maypole in the centre’. The hall was ‘festooned… with a profusion of spring flowers’. As well as the crowning of the Guild Queen and maypole dancing, the children performed a piece called ‘The Yearly Round’ featuring children representing the seasons, the months of the year, farmers, milkmaids and ‘the Spirit of Co-operation’ (WP 5 May 1905). In 1915 Woolwich Socialist Sunday School organised a May Day outing to Eltham Public Park (WP, 7 May 1915).

Return of the Maypole

The maypoles of the Middle Ages seem to have usually been just stripped tree trunks. Maypoles with ribbons were however known in France and seem to have been introduced into England to feature as part of the entertainments of the Pleasure Gardens of London, such as those at Vauxhall and Ranelagh in Chelsea. Horace Walpole wrote of a 1749 visit to the latter that ‘in one quarter was a maypole dressed with garlands, and people dancing round it to a tabor and pipe and rustic music, all masked’ (Walpole, 1840). The supper boxes at Vauxhall featured paintings of May Day scenes by Francis Hayman.

The Victorians codified a series of maypole ribbon plaiting dances which were popularised through schools. A key vector for this transmission was Whitelands College in Roehampton, where generations of teachers were taught the dances as part of their teacher training. John Ruskin – art critic, philanthropist and Camberwell resident – had an important role in this. He was a friend of the College Principal, the Reverend Canon John Faunthorpe, and in 1881 helped initiate the first May Day festival there. Students at Whitelands have elected an annual May Monarch ever since with the main concession to modernity being that in 1986 the rules were relaxed so that a May King could sometimes be elected instead of a May Queen.

Maypole dancing became a feature of school life in South London and elsewhere. In Bermondsey for instance, the opening of the new Tanner Street playground on 11 May 1929 featured a Maypole dance by infants of Riley Street School (Bermondsey Labour Magazine, June 1929). Maypole dancing was not always confined to May – it featured for instance at the Shirley Street Sports Day in Bermondsey in July of that year (BLM, September 1929).

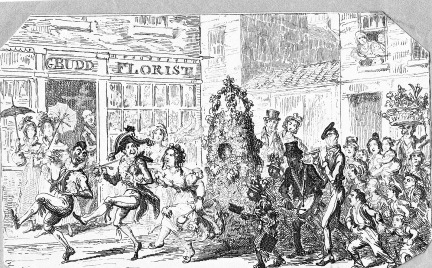

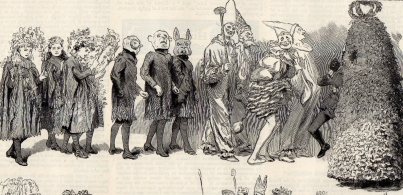

The maypole also featured in the May Day Fetes held at St Mary Cray in the 1890s organised by local paper mill owner, E.H. Joynson. The Graphic reported (10 May 1890): ‘Of all pretty revivals, one of the prettiest, the May Day Fete, attracted great crowds to the usually quiet Kentish village of St Mary Cray. The May Queen, attended by her maids of honour, had her throne of a triumphal car, drawn by four Sussex bullocks, with drivers in Old English costume. The procession was led by Druids, with flowing beards and flowing robes (one very much like Father Christmas, out of season), followed by Friendly Societies with their banners, and tilters on horseback, by maskers, clowns, and sweeps, Jack-in-the-Green, living chess characters, milkmaids leading a decorated cow, children representing wild flowers, maids with garlands, and a living pack of cards… The dance around the Maypole… attracted great notice’.

May Day in St Mary Cray, (The Graphic, 10 May 1890)

The following year 10,000 spectators turned out in the pouring rain. ‘The costumes… were entirely designed by Mr Joynson, of the paper mills, and were carried out at the mill under his personal superintendence… it betokened a very pleasant state of feeling between the employer and the employed that the latter should have entered so heartily into the spirit and enjoyment of the performance’ (Graphic 9 May 1891).

But this kind of paternalist May Day from above was already being challenged by a new kind of May Day event. The same issue of the Graphic reported May Day demonstrations, and in some cases riots, in various countries. It seemed that a new spectre was haunting Europe: ‘Nothing in its way could be more impressive than the fact that essentially the same ideas have captivated the imagination of the labouring population of every civilised country… in all the great centres of industrial life they are evidently of the opinion that it is possible for them to have shorter hours of work and higher pay, and that it is just and necessary that the possibility should be transformed into a reality’ (Graphic 9 May 1891).

6. THE WORKERS’ MAY DAY: ORIGINS TO 1930s

Origins

In the late nineteenth century a new layer of meaning was added to May Day, as the first of May became associated with the international workers movement. As we shall see, elements from traditional May Day celebrations came to be incorporated into socialist demonstrations – but was it just, as Hutton (1996) suggests, ‘a wholly fortuitous coincidence’ that ‘the strike which became the symbol of the American Labor Movement began upon 1 May’?. To answer this we have to examine the origins of the ‘Workers’ May Day’ in the struggle for an 8 hour day in the United States and elsewhere.

For the early workers movement internationally a key demand was for a reduction in the length of the working day. The 1884 Chicago congress of the Federation of Organized and Labor Unions (which later become the American Federation of Labor) declared that from May 1st 1886, it would impose an eight-hour working day in the United States by industrial action. Unlike most strikes which respond to particular events, this date was set several years in advance.

It is unlikely to have been a purely arbitrary date – but why the first of May? Dave Roediger (1997) has noted that in parts of the United States May 1st was known as Moving Day, the date when leases expired and when new terms and conditions of work were set for building tradesmen and others who worked outdoors. This would make it an obvious date for setting new hours of work. Of course the notion of May 1st as effectively the start of a new year might itself be related to older seasonal traditions. It is also quite possible that for some within the workers’ movement at the time the date had a symbolic value as a time of renewal, related to these traditions. Immigrants to the USA brought with them various May Day customs from their home countries. For instance a Maypole was famously set up at Merrymount in New England by Thomas Morton in the 1620s.

There does also seem to have been a precedent for radical movements to regard May 1st as significant. We have already seen that the Levellers’ ‘Agreement of the People’ was published on 1 May 1650. The proposed French Revolutionary Calendar renamed the month Floreal, with the opening day envisaged as a celebration of love and nature. The utopian socialist Robert Owen announced in 1833 that the New Moral World should begin on 1 May 1834 – Owenite ideas certainly had their influence in the US so this may have been a factor. On May Day 1820 the Cato Street conspirators, who had plotted to assassinate the British cabinet, were hanged in London.

It was also on 1 May 1776 that Adam Weishaupt founded the ‘Order of Perfectibilists’, later known as the llluminati, at the University of Ingolstadt. Apparently dedicated to the enlightenment ideas and critical of the absolute rule of kings and priests, this Masonic society was seen by reactionaries as the hidden hand behind every radical and republican stirring in 19th century Europe. As a case in point, the notorious anti-semite Nora Webster (1924) saw May Day as a plot of ‘the great German-Jewish company that hopes to rule the world’ led by ‘illuminized freemasons’ in the guise of socialists. She asked ‘Was it again a mere coincidence that in July 1889 an International Socialist Congress in Paris decided that May 1, which was the day on which Weishaupt founded the Illuminati, should be chosen for an annual International Labour demonstration?’. Well yes in all probability it was a coincidence.

Whatever the factors involved in choosing the date, the events of Saturday 1 May 1886 and the succeeding days are well documented. The eight hour day strike went ahead in parts of the USA, and by May 3 1886 perhaps 750,000 workers had struck or demonstrated (Roediger). In Chicago police killed two people when they opened fire on Monday 3 May during clashes outside the McCormack Reaper Works, where workers had been on strike since February. The following day a policeman was killed by a bomb thrown at a protest meeting in Haymarket square in the city. Eight anarchists who had been in the forefront of the 8-hour-day agitation in Chicago were convicted of murder, of whom seven were sentenced to death.

There was an international outcry against the trial and the sentences. In London those who spoke out included William Morris, Annie Besant (who had lived in Colby Road, Upper Norwood), George Bernard Shaw, Peter Kropotkin (then living at 6 Crescent Road, Bromley), Oscar Wilde, Edward Carpenter, Ford Madox Brown, Walter Crane, E. Nesbit (then living in Lewisham), Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling (who later lived in Sydenham). A meeting on the case was held at the Peckham Reform Club (Freedom, November 1897).

Nevertheless, four of the accused were hanged. The deaths in Chicago had a powerful impact across the world, not least on Jim Connell who was inspired to write ‘The Red Flag’ anthem in 1889 on a train to New Cross – he was living at 22a Stondon Park in Honor Oak at the time (Gordon-Orr, 2004).

The movement for a shorter working day did not die with those who became known as the Chicago Martyrs. In December 1888 the American Federation of Labour called for a national day of demonstrations and strikes on 1 May 1890, and this call was echoed in July 1889 by the international socialist conference in Paris. So it was that from 1890 May Day became an annual international festival of working class solidarity.

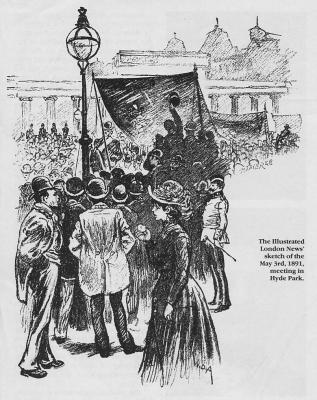

The 1890s

In London, May Day 1890 was marked by a huge demonstration in Hyde Park, a venue that was to become the focus for May Day protests for many years to come. May 1st 1890 actually fell on a Thursday, and saw London anarchists holding a meeting at Clerkenwell Green. The main demonstration took place [after some political shenanigans- Ed: here’s Engels on the subject] on the following Sunday – May 4th – and saw contingents heading towards Hyde Park from all over London. A description from the South London Press of the attendance of the North Camberwell Radical Club and Institute’ provides an insight into how local groups organised themselves for the march:

‘A goodly contingent went from this club to take part in the monster eight-hours demonstration. The procession was headed by the club’s excellent band, which discoursed some well-chosen music on the way. A large banner followed, bearing the device in front, ‘The Proletariat Unite’, and on the reverse side the legend, ‘Eight hours’ work, eight hours’ pay; Eight hours’ rest, eight bob a day’. Mr Oodshorn devised and executed the banner, which was very effective. Mr J. Harrison (chairman of the club) headed those who marched in front, and Mr. H.J. Begg accompanied the contingent until it took its place in the general ranks. Two breaks followed the pedestrians – one full of ladies, and one containing those of the sterner sex who were not equal to a four-hours march on a warm day. Messrs. Benstroke and J.Sage (chairman of the Political Council) acted as marshalls. The breaks, which added greatly to the effectiveness of the procession, were under the charge of Mr A. Boreham (chairman of the Entertainment Sub-Committee). The contingent arrived in the park in time to hear some good speaking from No.7 Platform, and afterwards Mrs Besant’s stirring speech from the Socialists’ platform. The whole affair was excellently managed, and good humour and good order prevailed throughout’ (South London Press, 10 May 1890).

The next few years saw this route being repeated. In 1891, the North Camberwell Radical Club was again said to have been busy in preparing for the 8 hours demonstration in Hyde Park (SLP 25 April1891). The Club was based in Albany Road.

In 1892 a crowd estimated between 300 and 500,000 marched from Westminster Bridge to Hyde Park, with 350 banners and 110 bands. An observer reported that ‘The great staple industries of London, the dockers, the stevedores, the coal-porters, the gas-workers… railway workers, and so on, came first: and then a whole host of miscellaneous trades, led by little Jew cigar and cigarette-makers from the East End… The Workgirls… were in great force. The chocolate-makers had a smart little wagonette all to themselves, from which they dispensed ‘Union Chocolate’ in penny packets’ matchgirls’. Those present included Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann and Louise Michel (all of whom spoke), Eleanor Marx and the elderly Frederick Engels. The crowd was so large that ‘the South London contingent, led by John Burns, never got in at all, and it turned sadly back without a chance of attending the meeting. In a word, London has never seen such a gigantic turn-out of the forces which create her wealth’ (Penny Illustrated Paper, 7 May 1892)

In 1892 a crowd estimated between 300 and 500,000 marched from Westminster Bridge to Hyde Park, with 350 banners and 110 bands. An observer reported that ‘The great staple industries of London, the dockers, the stevedores, the coal-porters, the gas-workers… railway workers, and so on, came first: and then a whole host of miscellaneous trades, led by little Jew cigar and cigarette-makers from the East End… The Workgirls… were in great force. The chocolate-makers had a smart little wagonette all to themselves, from which they dispensed ‘Union Chocolate’ in penny packets’ matchgirls’. Those present included Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann and Louise Michel (all of whom spoke), Eleanor Marx and the elderly Frederick Engels. The crowd was so large that ‘the South London contingent, led by John Burns, never got in at all, and it turned sadly back without a chance of attending the meeting. In a word, London has never seen such a gigantic turn-out of the forces which create her wealth’ (Penny Illustrated Paper, 7 May 1892)

In 1897 the Demonstration from Embankment to Hyde Park on Saturday 1 May included contingents from Camberwell and Battersea (Times 3 May 1897); in 1898 there was a large ‘International May Day Demonstration’ from Embankment to Hyde Park in the pouring rain (Times 2 May 1898).

Crystal Palace and Walter Crane

The turn of the new century saw the main May Day event moving to South London at the Crystal Palace. The Palace had been hosting May Day celebrations for many years. In the 1850s, William Husk of the Sacred Harmonic Society had helped recreate a Tudor-style May game there (Hutton, 1996). On May Day 1866 ‘a great concert of five thousand voices was given by children and others connected with the metropolitan schools… Ethardo [a circus performer] also reappeared, his lofty pole being converted into a gigantic maypole. On the following day Mr Charles Dickens kindly undertook to give a reading of Little Dombey’ (PIP 5 May 1866). In 1898 a ‘Crystal Palace May Day Festival’ had included ‘May-Day Sports and Maypole dance’ with a programme featuring ‘the Clan Johnson, Scottish Dancers and Champion Pipers and an Old English Maypole Dance’ as well as a ‘Grand May-Day Concert’ featuring ‘madrigals by the Crystal Palace Choir’ (advert in the Times, 1 May 1899).

May Day 1900 was different in tone. The Times reported that 12,000 took part, including ‘about 150 associations connected with the Social Democratic Federation and London Trades Council’. Six platforms were set up and the resolutions carried included one asserting ‘their determination to overthrow wagedom and capitalism, and to establish by united efforts that international cooperative commonwealth in which all the instruments of industry will be owned and controlled by the organised communities and equal opportunity be given to all to lead healthy, happy human lives’ (Times, 2 May 1900).

The event did though include more traditional May Day elements alongside the socialist speeches: ‘There was a procession at half past two, and meetings at 3 o’clock. There were also cycling and athletic sports, a Maypole dance and other attractions. The programme concluded with a display of fireworks by C.T. Brock & Co., including a special set Labour piece by Walter Crane’ (South London Press, 5 May 1900). Other attractions of the ‘International Labour Festival’ included a variety show and a performance of Bernard Shaw’s ‘Widowers’ Houses’ (advert in Times, 1 May 1900).

The artist Walter Crane recalled: ‘Labour’s May Day, which has become an international festival in the Socialist movement, was this year celebrated at the Crystal Palace, which certainly afforded plenty of space for the gathering, as well as entertainment and refreshment in the intervals of the functions. A vast meeting was held under the dome, and this was addressed by many of the leaders, such as Mr. H. M. Hyndman, Mr. G. N. Barnes, Secretary of the Amalgamated Engineers (and now in Parliament), Mr. Pete Curran, Mr. Ben Tillet, and many others. I made a design for a set piece for the firework display which was carried out on a gigantic scale and with remarkable success by Messrs. Brock. It was a group of four figures, typifying the workers of the world, joining hands, a winged central figure with the cap of Liberty, encircled by the globe, uniting them, and a scroll with the words ‘The Unity of Labour is the Hope of the World’. It was the first time a design of mine had been associated with pyrotechnics. I was rewarded by the hearty cheers of a vast multitude.’ (Crane, 1907 – Crane dates this event to 1899 while The Times reports it as being in 1900, though it is possible it was repeated in both years).

Crane was a key figure in the creation of a May Day iconography that combined socialist values with the familiar ‘Merrie England’ imagery of may queens, garlands and angels. Crane’s earliest May Day work was a series of illustrations for a fairy tale by John Wise, The First of May, a Fairy Masque (1881). His drawings depicted animals dancing round a maypole and fairy scenes. Soon he was to add a political dimension to such imagery. While for some conservative Victorians, the recreation of May Day festivities harked back to a traditional social order where everybody knew their place, socialists like Crane and William Morris mobilised visions of medieval pageantry and a lost rural idyll in the service of a critique of what they saw as the squalor of industrial capitalism.

The contrast between May Day festivities and the world of work had been drawn before. In May Day songs from the 1860s, WC Bennett had written: ‘Your fathers met the May, With laughter, dance, and tabor; Come, be as wise as they: Come steal today from labour… Talk not of want of leisure; Believe me, life was made, For laughter, mirth and pleasure, Far more than toil and trade’ (PIP 7 May 1864); and ‘Out from cities haste away, This is earth’s great holiday: Who can labour while the hours, In with songs are bringing May’ (PIP 5 May 1866).

But for most workers skipping into the fields on a work day was not an option – it was only the reduction of working hours and the extension of weekends and holidays that could create the free time for festive celebrations.

As the historian Eric Hobsbawm (1998) has argued, the act of demonstrating, and in some cases striking, on May Day made this connection directly: ‘It was thus both a gesture of class assertion and class struggle and a holiday: a sort of trailer for the good life to come after the emancipation of labour… Seen in this light May Day carried with it a rich cargo of emotion and hope’.

Crane’s images gave a strong visual identity to this ’emotion and hope’ and were precisely adverts ‘for the good life to come’, in which carefree, healthy proletarians dance in the open air. After May Day became the focus of an annual socialist demonstration, Crane produced a May Day cartoon every year. These were mostly published in Justice, paper of the Social Democratic Federation, but they were also printed for sale separately. Examples included ‘The Triumph of Labour’ (1891) ‘The Workers May Pole’ (1894) ‘A Garland for May Day’ (1895) ‘John Ball’s Creditors’ (1900), ‘The Goal’ (1904) ‘Socialism and the Imperialistic Will O’ the Wisp’ (1907), ‘A Posy for May Day and a Poser for Britannia’ (1910) and ‘The Triumph Car for May Day’ (1911).

Socialism and the Seasons

In addition to the main London demonstration, May Day was often marked by local events. In 1905, for instance, there was a ‘tremendous gathering’ in Woolwich’s Beresford Square for a May Day demonstration sponsored by Woolwich Independent Labour Party and Woolwich and District Trades and Labour Council. Speeches at this event show how in England at least, many saw a clear continuity between the workers’ May Day and the more traditional festivities. Mr. H.S. Wishart, the Chairman, declared: ‘long ago the workers were wont to assemble on May Day to enjoy themselves. Today the workers were nominally free, but their real condition was worse than in days gone by. Today the workers were really slaves owned by the masters, slaves to wages, and to the men who controlled the money power of the world’. Councillor Grinling elaborated: ‘May Day was the birthday of summer, and they were assembled on that occasion in spirit with the men and women all over the universe who on May Day saw the sun rise on a new summer and a new season. The lives of all were dependent upon the four seasons, yet livers in towns were so unfamiliar with the beauties of the earth and sky that they forgot the changing seasons’. He went on to herald the summer of the Labour Movement, with the ‘people rising to take… a fuller and juster share in all that comes from Mother Earth’ (Woolwich Pioneer, 28 April 1905, 5 May 1905).

Similar sentiments were voiced in Bermondsey Labour Magazine in the 1920s: ‘All over the world the organised Labour movement has set aside May 1st as a special holiday or festival. From pagan and mediaeval times the period of the year marked by the beginning of the month of May has been held as a time of rejoicing at the return of sunshine and warmth after the greyness and frost of winter. In the young trees the sap is rising. Flowers and buds and blossoms are lifting up their faces to the sun. Shall not humanity do likewise and rejoice with them? May Day for our ancestors, therefore, symbolised the Dawn of Hope – hope of harvest, hope of fruit, hope of plenty, hope of the glad time to come after the bleak discomfort of the past months. For Labour and the toiling masses everywhere, May Day signifies the new hope of the better days that are to be. It proclaims the bursting of the fetters of convention; it declares deliverance from the bondage of wage slavery; it tells of the times when the disinherited shall share in the beauty, the joy, the dignity of life. And, as the men of the past proclaimed their faith in the future by song and dance and merrymaking, by procession and pageant and revel, so the Labour and Socialist Movement over Europe demands that May 1st shall be a day of demonstration, of carnival, of freedom from work. The celebration of May Day is Labour’s proclamation to the tyrants of Land and Capital that the mighty are to put down from  their seats and that the people of low degree are at long last to enter into their inheritance… May Day is Labour’s International Holy-day’ (The Meaning of May Day, Bermondsey Labour Magazine, May 1924).

their seats and that the people of low degree are at long last to enter into their inheritance… May Day is Labour’s International Holy-day’ (The Meaning of May Day, Bermondsey Labour Magazine, May 1924).

The following year’s May edition of the magazine included ‘The Workers’ Song of the Springtide’ which bemoaned: ‘They sing of the merry springtide, Which is sweet to them indeed, These wealthy whom we are clothing, Whose little ones we feed; But to us is the sun a furnace, The spring but a burning cauldron, And life but a prison cell’. Still, the author proclaimed ‘the time will come when the

beauties of earth shall be for all… When the spring shall come laden with gladness, And pleasure instead of pain’ (BLM, May 1925).

The Nineteen Twenties

The official labour movement in Britain generally timed the main May Day demonstrations so that they did not fall on a working day. 1920 was an exception – May Day fell on a Saturday, still a normal working day for most, and 6 million workers took a holiday. At the Woolwich Arsenal, the Shop Stewards wrote to the management informing them that the workers there had ‘decided to celebrate the First of May as a Labour Holiday’ (WP 30.4.1920). On the day ‘there were so many absentees from work that some of the departments had to shut down’ (WP 7 May 1920).

Many of them joined a demonstration on Dartford Heath that included contingents who had marched from Woolwich, Welling, Erith, Bexley Heath, Dartford and Crayford. It featured the Woolwich Labour Protection League drum and fife band and songs from the Woolwich Socialist Sunday School. There was also a children’s wedding procession with girls in home made paper dresses (KM 7 May 1920). The resolution passed at the mass meeting declared:

‘This meeting of workers assembled on Dartford Heath, May Day, 1920, sends fraternal greetings to the Proletariat of the World, and heartily rejoices at the continued success of the Russian Revolution. Recognising that the ever increasing burdens placed upon us are entirely due to Capitalist Domination, we urge the International Solidarity of our Class to bring about its emancipation from this system. Furthermore, we condemn the action of the British Government, in regard to its Militarist oppression of Ireland, Egypt and India’ (WP 7 May 1920).

As well as the Dartford demonstration, The South London Press reported a ‘gigantic muster in Hyde Park’ at the end of the May Day demonstration from Thames Embankment (SLP 7 May 1920).

In 1926, May Day marked the effective start of the General Strike. On Saturday May 1st, one million miners were locked out for refusing to accept a pay cut and longer hours. The same day workers at the Daily Mail walked out on strike refusing to print the paper’s lead article ‘For King and Country’. This marked the point of no return and from Monday May 3rd millions of workers went on strike in support of the miners. After nine days they were ordered back to work by the Trades Union Congress.

On Saturday May 1st itself at least 100,000 people marched from the Embankment to Hyde Park, including many from South London. ‘The Bermondsey contingent in the London May Day procession was the finest and most impressive that had been organised. At 11 am we lined up outside the Bermondsey Town Hall with our band, banners and brakes. Almost every section of organised workers in the Borough was represented’. The Bermondsey contingent met up with marchers from Deptford and Camberwell by St George’s Circus (BLM June 1926). Later there was a May Day Festival and Dance at Bermondsey Town Hall featuring ‘Bert Healey’s Famous Dance Band’ and ‘Limelight colour effects and novelties’ (BLM, April 1926).

May Day messages in the Bermondsey Labour Magazine reflected the turbulent times. New Cross (No.1 Branch) of the National Union of Railwaymen declared ‘Greetings to the workers in “All Labour Bermondsey”. International Labour Day, 1926, will go down in history as the turning point in the inevitable all conquering march towards emancipation… Let us honour the memory of our valiant pioneers, by striving for Unity – at home and in all the lands, irrespective of race, colour or creed’. Bermondsey NUR sounded a more seasonal note: ‘Let us therefore strengthen our own organisations, industrial and political, and continue every day this May Day Spirit of Brotherhood and Comradeship to meet the present Capitalist offensive. We read how in London before the ugly factories were built children danced the Maypole and men and women joined in their games on the people’s commons. Spring had come, birds were beginning to sing, flowers to bloom, and nature putting on her best. It is because of this, we workers think of the laws that are unjust and bind us. We long to repeal them and make Liberty and Freedom for all to enjoy’ (BLM, May 1926).

The history of the General Strike in South London is beyond the scope of this text, but it was strongly supported in most areas. There were clashes between strikers and police at the Elephant and Castle (Past Tense, 2005) and at the New Cross Tram Depot in New Cross Road (Gordon-Orr, 2004).

The Nineteen Thirties