On Sunday 18th January 1981, 13 black youths, all between the ages of 15 and 20 years old, were killed in a fire at a birthday party for Yvonne Ruddock and Angela Jackson, at 439 New Cross Road, in the heart of the South London neighbourhood of New Cross.

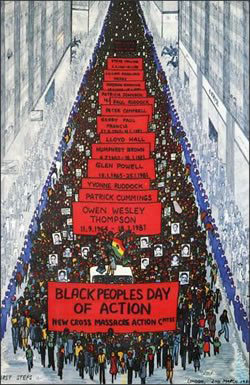

The victims of the New Cross fire were Humphrey Brown, 18, Peter Campbell, 18, Steve Collins, 17, Patrick Cummings, 16, Gerry Francis, 17, Andrew Gooding, 14, Lloyd Richard Hall, 20, Patricia Denise Johnston, 15, Rosalind Henry, 16, Glenton Powell, 15, Paul Ruddock, 22, Yvonne Ruddock, 16, and Owen Thompson, 16.

Twenty seven others were seriously injured.

Anthony Berbeck, caught up in the fire, was believed to have committed suicide following the trauma of the event, in July 1983.

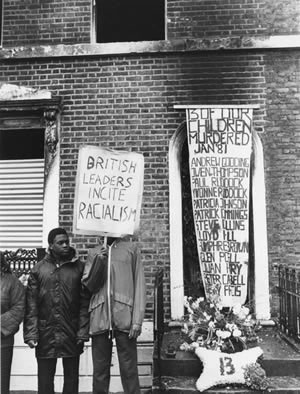

The police initially concluded that the fire was caused by a firebomb, and many believed that it was a racist attack – not unreasonably, as racial attacks and racist fire-bombings had been endemic against black and asian communities throughout the previous decade.

“The suspicion was that it was a racial attack. A lot of that was happening in the country at the time, in the East End of London, everywhere. So it seemed perfectly reasonable to believe the place had been fire-bombed. I genuinely believe that, and everybody believed that at the time. A policeman told Mrs Ruddock on the night of the fire that there was a fire-bomb – from his mouth came the words.”

Over the preceding two decades, elements of the political class and the media had stoked a climate of racism in which horrific levels of brutality, including murder, became routine. The incidence of racist attacks was closely related to government and media-inspired resentment against immigration; of the 64 racist murders between 1970 and 1986, 50 occurred in the five years – 1976 and 1978-81 – when immigration scares ‘reached fever pitch’.

The New Cross fire occurred in the context of racist arson attacks across South London, particularly in New Cross and Deptford. In 1971, three petrol bombs had been thrown into an African-Caribbean party in Sunderland Road in Ladywell. The immediate response of the police was to arrest eight members of the Black Unity and Freedom Party on their way home from visiting victims in Lewisham hospital. Both the Moonshot youth club in New Cross and the Albany centre in Deptford had been burnt out by fascists in the preceding few years.

After initially suggesting that the New Cross Fire might be a racist attack, the police quite quickly back-pedalled on the racial aspect of the tragedy. Police officers had told Mrs Ruddock twice, within the first couple of hours of the fire, that it had been caused by a petrol bomb. The first officer to point to arson was on the scene outside the house, the second at King’s College Hospital. Other witnesses reported the suspicious behaviour of a man who pulled up and drove off in White Austin Princess. Four days later, the South East London Mercury reported that the police were trying to trace the driver of the vehicle which was parked outside the house (22 January 1981)

Survivors and witnesses were grilled by the police and treated with suspicion, and hostility, even at the inquest: “I was one of the last people to give evidence, and so I had to watch everyone – you know, all my friends go in and do their bit, and then it was me. And I was scared. But I used the inquest as an opportunity to let everyone know what had happened the night when the police did interview me, ‘cos I felt as if they were asking me the questions and then they were answering them themselves. So I used that as an opportunity to say, Well, okay, this was what was happening. But I think the build-up to it was a lot worse than the actual day was. Bishop Wood was a big help. And he was in there with me, and I suppose I needed someone in there with me, anyway. And he was my support, really, yeah. It was an experience, for my age. It was an experience, and not one I’d like to go through again in a hurry. Yeah, it was terrible. Every morning, you’d pull up at the court and it would be sort of, like, cameramen and all that, every day…. There were times when I did feel, especially when 1 was being interviewed by the police, I felt like, Hold on, I am the victim here, yet I feel as if I’m a suspect.”

Family members and the local black community felt the attack was ignored and belittled – there was little serious press coverage or official sympathy. Police fed stories to the media about gate-crashers and cannabis at the party, detained black youth for questioning and twisted evidence at every turn to ‘prove’ that the fire was not started by racists. Despite the fact that the New Cross massacre was the worst atrocity suffered by black people in Britain, it took the Day of Action to force MPs to raise it in parliament. Local Labour MP, John Silkin, said not one word in the House of Commons and for three weeks did not send even a message of condolence to the families. As one woman stated at a press conference, if the fire had taken place in a dog’s home and killed 12 dogs, there would have been more response.

Family members and the local black community felt the attack was ignored and belittled – there was little serious press coverage or official sympathy. Police fed stories to the media about gate-crashers and cannabis at the party, detained black youth for questioning and twisted evidence at every turn to ‘prove’ that the fire was not started by racists. Despite the fact that the New Cross massacre was the worst atrocity suffered by black people in Britain, it took the Day of Action to force MPs to raise it in parliament. Local Labour MP, John Silkin, said not one word in the House of Commons and for three weeks did not send even a message of condolence to the families. As one woman stated at a press conference, if the fire had taken place in a dog’s home and killed 12 dogs, there would have been more response.

“The action committee – which was Darcus Howe then, and Mrs Phoenix – they wrote a letter to the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and one to the Queen. And they never get a reply until six weeks after. Six weeks after! That’s when they get the reply. But, I think it was two weeks after the New Cross march, they had one in Ireland and forty-eight died. That was a Sunday, too, ‘cos that happened this Saturday night, some disco, and forty-eight people die. And straight away condolence went from here to there, and we had to wait for six weeks reply. That was bad! Bad, that very bad. Something happen in your country and you write to the authorities and you didn’t get no response from them. And six weeks after the time, that couldn’t look good, and 1 felt very bad about that. That wasn’t good enough, six weeks.”

To the families, friends of the dead, and wider communities they came from, the lives and deaths of black people were considered unimportant; black lives did not matter.

Racist attacks on black people in Britain had been part of black communities’ lives since the 1950s; the activities of fascist groupings like the National Front and the British Movement had been both capitalising on white British racism and encouraging and whipping it up though the 1970s.

An inquiry was launched, led by South London head of CID, Commander Graham Stockwell This enraged black activists, as Stockwell had been instrumental in reinstating the incitement to riot charges against the Mangrove Nine (including Darcus Howe). Stockwell’s form was not lost on the campaigners. Darcus Howe was convinced that the decision to put Stockwell in charge of the investigation was essentially “a political decision, because he knew some of the characters in the game”. Relations between the police and the local community were already strained, with the Metropolitan Police accused of lacking urgency. There was a rejection of moves by police to bring the black community behind the Community Relations Councils (CRCs) and the Commission for Racial Equality, as this was seen as undermining an independent struggle for justice.

The NCMAC also established a Fact Finding Commission on 20 Jan 1981 to compile its own evidence through interviews with survivors and with the bereaved. It not only carried out an independent investigation as to what had happened, but also found out through such interviews about the methods that the police were using to obtain their information. Allegations were made that some of those interviewed by police had been forced into signing false statements under pressure. The Fact Finding Committee discovered that the police were detaining the young survivors of the fire, in some cases without their parents’ permission, and pressurising them into signing statements saying the fire was the result of a fight at the party. 11-year-old Denise Gooding, whose 14-year old brother Andrew had died in the fire, was questioned in a police station for many hours before finally being released at 1 a.m. During the interrogation, she was repeatedly told by officers not to lie, just to tell them there was fighting in the house. NCMAC would eventually expose how child witnesses were made to sign false statements under police duress at the Inquest into the fire, by which point the Met had abandoned the theory of a fight as the cause of the fire altogether. However, as La Rose later pointed out, the movement had been forced to “exercise every ounce of alertness and vigilance to stop the police framing a group of young blacks who were at the party”.

Rumours of a racist attack carried out by far right groups were too easily overlooked by the police.

For many Black Londoners the New Cross Fire was the last straw. The fire was to have a long and traumatic impact on black consciousness in the UK – in the short term it galvanised a sudden and angry movement in response. New Cross was after all, the arena for mass resistance to a National Front march in 1977: locals were less and less prepared to be pushed around by racists or treated like shit by the police.

The New Cross Massacre Action Committee, chaired by John La Rose, was mobilised to protest at the apparent bias and mishandling of the police investigation into the fire, to challenge the indifference shown by the government, and to highlight distorted media coverage. Fuelled by a history of attacks on black people, including several incidents in the Lewisham, New Cross and Deptford areas, suspicions soon arose about police methods of detection and inherent racism.

The New Cross Massacre Action Committee coalesced around three members of the Black Parents Movement – Darcus Howe, John La Rose, and Roxy Harris, together with Alex Pascall – who formed a delegation and visited Mrs Gee Ruddock, owner of 439 New Cross Road, at the house of black community leader Sybil Phoenix. Mrs Ruddock had lost both of her children in the fire.

“’I was in a meeting of the Black Parents’ Movement. There was an alliance between the Black Parents’ Movement, Race Today, which I edited, and the Black Youth Movement. That would be at Finsbury Park, around John Larose’ and the New Beacon Bookshop, and we were there on Sunday night and a phone call came, I think it was via Sibyl Phoenix, to tell us that this terrible thing had happened on the Saturday. And the first thing we did was to stop the meeting, adjourned it, and went. And we met Mrs Ruddock and Sibyl Phoenix and they invited all of us down on the Monday to the Moonshot Club, youth club.” (Darcus Howe)

“’I was in a meeting of the Black Parents’ Movement. There was an alliance between the Black Parents’ Movement, Race Today, which I edited, and the Black Youth Movement. That would be at Finsbury Park, around John Larose’ and the New Beacon Bookshop, and we were there on Sunday night and a phone call came, I think it was via Sibyl Phoenix, to tell us that this terrible thing had happened on the Saturday. And the first thing we did was to stop the meeting, adjourned it, and went. And we met Mrs Ruddock and Sibyl Phoenix and they invited all of us down on the Monday to the Moonshot Club, youth club.” (Darcus Howe)

The Pagnell St/Moonshot Youth Club in Pagnell Street, New Cross, was a local community centre established for and by black youth: survivors had gathered here in the early hours of Sunday morning. Sybil Phoenix, who ran the Moonshot, had arrived at the scene of the fire while bodies were still being carried from the building. Phoenix had been asked by the police to try to find people who had been at the party to help identify the badly burned bodies. She was to play a crucial role supporting the bereaved through the devastation of the days and weeks that followed.

On the Sunday after the fire (20th January 1981), a mass meeting was held at the Pagnell Street Community Centre in New Cross, attended by over 1000 people.

“And we thought, or I certainly thought, Well, we’re going to meet a committee of about ten people. When we got there there were three hundred people. John and I were, by and large, two of the major figures in that alliance, so I said, “John, this is trouble. This is it.” But, you see, I wasn’t surprised that much, because the black people were starting to gather.” (Howe)

At the beginning of the meeting, Lewisham Police Commander John Smith arrived uninvited to address those present: his words were drowned out by angry shouts of ‘ Go away murderer! ’. Smith, visibly shaken, by the experience, later called his reception ‘ rather sad ’. Flanked by Scotland Yard Press Officer, Bob Cox, he left the building without speaking. So much anger against the Met was hardly surprising – police had failed to investigate a string of suspected racist attacks in the area properly. The Met’s failures, particularly when dealing with suspected arson, were legion. The Moonshot club itself had burnt down in December 1977 a few weeks after reports of it being identified as a target for attack during a local meeting of the National Front. Nonetheless, the police excluded arson as a possible cause. Similarly, the police’s decision to rule out foul play when The Albany Theatre in Creek Road, Deptford, burnt down in August 1978 caused rage locally.

“And then we decided to have a public meeting. This is Monday, for Saturday, and when we went down there were about three thousand people.”

The second meeting ended with a demonstration to 439 New Cross Road, which blocked the main road (the A2) for several hours.

A series of public meetings were held across London to encourage support. There were also regional committees set up across the country, in Leicester, Manchester and Rugby, as well as committees in North, West, and South East London.

“And we started to meet every Tuesday. It was a kind of black assembly – hundreds of people came every Tuesday. John Larose was chair. We had a committee which I was on, the officers were officers of Race Today in Brixton, by which time we could organise. We took a political decision to do that, for one simple reason: every single week you would hear clashes between the police and blacks all over London and it was becoming something of importance. There were other issues at large, and I said, “Well, if they’re going to kill so many kids in a fire, we have to mobilise and show them we got some power in this place, and only way to do that is to call a general strike of blacks.” That was at the back of my mind. I discussed it with Race Today people. I said, “Let’s see how it goes ‘cos I think we can pull this one off.” (Darcus Howe)

It was the Black People’s Assembly which decided on holding a Black People’s Day of Action, on a working day, set for Monday 2nd March 1981. The committee planned a campaign of support for a demonstration on that day.

“So we decided to call a day of action, the meeting, and they decided it should be on a weekday, a working day, and I thought, “Well, let’s see how it goes.”

John La Rose, the chair of the NCMAC, recalled in an interview:

John La Rose, the chair of the NCMAC, recalled in an interview:

‘People would be saying, “Man we have got to do something about this thing. The police cannot get away with this thing!” That kind of talk went on. And they said, “Yes we’ll go on a march.” “Where are the guns?” That kind of talk…And I said, “Have you heard of a man called Brigadier Frank Kitson, Low Intensity Operations? If you haven’t read his book then you should read it. Because if you are talking about going to Parliament with guns then you have to take on Kitson.” He had been the Commander in Northern Ireland, he was GOC in Britain. I said, “Let’s talk seriously, you are starting at the end, let’s start at the beginning.”

‘We had that sort of interchange all the time at the meetings, very open, free meetings. So they said, “OK we’ll go on a march.” We said, “Well, what day are we going to march?” Because the normal marches took place on a Sunday, when nobody’s working, everyone’s home, the people said that they wanted it to be on a day when the British are bound to take notice. So what day? We had to disrupt British society; that was absolutely clear. That is what we were saying in that movement. We wanted to snarl up traffic all over London.

‘So we decided it must be a Monday; that came from within the audience. We wanted to make this place realise that we’re serious and we’re going to disrupt the whole of British society. We aren’t going to work that day…

‘What demonstrations in the past usually did was to march on Hyde Park into Whitehall. We said we were going to go where the people are going to know that this is happening, we’re going to march in all those areas – like Peckham – before we come to Blackfriars Bridge. That way you are going to hit that area of London with all those people who are really concerned about what’s happening in the whole New Cross area, and then march through the financial centre, the City, and shake up the place, terrify them.x

The Black People’s Day of Action saw the biggest political mobilisation of black people seen in Britain up to that point. 20,000 black people and their supporters marched over a period of eight hours from Fordham Park in New Cross, through Peckham, Elephant and Castle, across Blackfriars Bridge, into Fleet Street, Regent Street, then Cavendish Street and finally into Hyde Park, with banners and placards with slogans including: ‘Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said’, ‘No Police Cover‑Up’, ‘Blood Ah Go Run If Justice No Come’, ‘New Cross Massacre Cover Up’; ‘Forward to Freedom’, ‘Babylon will fall’; ‘No stopping us now we are on the move’; ‘No Rights, No Obligations’.

Attempts by the police to control and restrict the scope of the march had failed. As the Day of Action drew closer, Darcus Howe entered into tense negotiations with the authorities over the route and date of the march. Howe and John La Rose headed a small delegation which met with Inspector Pollinghorne, who had been placed in charge of policing the march, at Brixton Police Station in late February. The NCMAC proposed route of the march went from New Cross over Blackfriars Bridge, through the City and Fleet Street, past Scotland Yard and the Houses of Parliament before finishing in Hyde Park some 17 miles later.

Attempts by the police to control and restrict the scope of the march had failed. As the Day of Action drew closer, Darcus Howe entered into tense negotiations with the authorities over the route and date of the march. Howe and John La Rose headed a small delegation which met with Inspector Pollinghorne, who had been placed in charge of policing the march, at Brixton Police Station in late February. The NCMAC proposed route of the march went from New Cross over Blackfriars Bridge, through the City and Fleet Street, past Scotland Yard and the Houses of Parliament before finishing in Hyde Park some 17 miles later.

The route was symbolic. It had been picked so the protestors could express their disapproval at the distorted press coverage of the fi re, protest at the police’s handling of the investigation and so that the parents of the dead and members of NCMAC could hand in a statement to Parliament voicing concern at the lack of a government response.

Inspector Pollinghorne objected to the length and route of the march and said it should go through the Old Kent Road, a route which the campaign had already rejected. Howe defended the NCMAC’s preferred route, which had been designed to maximise the support and participation of the black community by going via Camberwell and Peckham. Pollinghorne demanded to know how long it would take the protestors to walk the 17 miles. Howe replied: ‘ you’re a military man, Inspector, we plan to advance a mile a day ’. At this, Pollinghorne walked out. The meeting lasted barely 5 minutes.

The police, in particular, felt large demos of angry black people to be a challenge to their control of the streets. London’s Black population felt they could be burned to death, without much comment, but god forbid they take to the streets in anger.

Darcus Howe recalled that the weather on the morning of Monday 2 March was beautiful; not cold but temperate and bright. He arrived at Fordham Park next to the Moonshot in good time and watched the marchers assemble in awe as wave upon wave came down the hill into the valley to join him in the park. Buses, organised by the NCMAC, kept arriving carrying black people from across the country. Hundreds of school children walked out of their schools to join the demonstration.

“The start of the demonstration was in a valley. You came down a hill in this little valley. And I was there, commander in chief, really, on the day, dealing with the stuff. I was in charge of the big truck, and I was in charge of the mike. So I was settled in. I was there on time, and beautiful weather, not cold, just temperate, bright sun, and waves and waves and waves and waves and waves of black people coming down that hill. It was a Charge of the Light Brigade… And off we went: “Thirteen dead and nothing said.” That was the slogan. “Thirteen dead and nothing said.” So the whole organisation of the march was around the fact that we can’t get an explanation from anybody.” (Darcus Howe)

“In the wake of the New Cross Fire we took a decision very early in the first meeting that it was a massacre politically. We decided that the protest would be Black~led and we decided that we would mobilise the whole country from a central co~ordinating group. I can remember very vividly being part of the debate. It was clear that we didn’t want it to be part of a commission or whatever because those bodies are not political bodies. If we were to wage any struggle, it had to be a political struggle, purely based on the resources of the community. You don’t apply for grants to take political action!” (Trevor Sinclair)

The march had been planned carefully. The stewards, who wore identification berets, were briefed by Howe to show discipline and restraint in the face of police provocation, ‘otherwise the march would collapse into a mass violence and the point would not be made’. With the Collective acting as chief stewards, he knew that if anything went wrong ‘ we would be held responsible ’.

The march had been planned carefully. The stewards, who wore identification berets, were briefed by Howe to show discipline and restraint in the face of police provocation, ‘otherwise the march would collapse into a mass violence and the point would not be made’. With the Collective acting as chief stewards, he knew that if anything went wrong ‘ we would be held responsible ’.

The police had said they wanted the march to start at 11.30 a.m. At 11 a.m., Howe called over to one of the officers and said ‘ Let ’ s go ’ in the hope it would upset any plans they might have to disrupt the march along the route. It was tactical flourishes like this which led Linton Kwesi Johnson to christen Howe with the nickname ‘ General ’. Tactics aside, Howe opines that the police were unprepared in a second sense. From studying James, from his experiences in the Caribbean and America, from travelling the country during the Lindo Campaign, from the Basement Sessions, and his run-ins with the police, Howe was prepared for the Day of Action. The event was unprecedented, but Howe’s years of experience organising campaigns and his theoretical understanding of the dynamics involved in mass protest meant that he was as prepared as anyone for the march. The police, by contrast, had no idea what they were dealing with. “They underestimated us. . . . They thought we were a load of little, stupid, black people.” The police were caught off guard by the scale of the march and the sophistication of the organisation. “There had never seen that size demonstration of black people before. So the police didn’t know culturally what to do”. (Howe).

As the march set off along New Cross Road, Howe could see that many thousands had missed school or work to protest. By the time that the front of the march arrived at the remains of 439 New Cross Road half a mile away and stopped to pay its respects to the 13 young lives lost in the inferno, the tail end of the march had not yet left the Fordham Park.

“… undoubtedly, [it was] black people, in the leadership of the march. In the main, if you look at street demonstrations, even street demonstrations around issues that affect black people, you get a sense that white people were somehow in command of events. They’d organised it. This was black organised, black led and you felt that. So it was very much a black community event. And then the numbers who joined it, that was significant, as you went along. But also in some parts of the march the hostility, directed by people who were undoubtedly racist…” (Darcus Howe)

As the mass of people passed through Southwark towards Blackfriars Bridge, the organisers reckoned that somewhere in the region of 25,000 people may have been on the march. When the chief stewards tallied their numbers together at the end, the final figure they arrived at was a little over 20,000. There was a sense that the police were frightened, that they had never seen anger from the black community on this scale before and that the movement which had mobilised that day ‘shook them to their roots’ .

As the mass of people passed through Southwark towards Blackfriars Bridge, the organisers reckoned that somewhere in the region of 25,000 people may have been on the march. When the chief stewards tallied their numbers together at the end, the final figure they arrived at was a little over 20,000. There was a sense that the police were frightened, that they had never seen anger from the black community on this scale before and that the movement which had mobilised that day ‘shook them to their roots’ .

When the march got to Blackfriars Bridge, it started to rain. A small delegation consisting of John la Rose and the victims ’ families left the head of march to take their protest to Parliament. A group of about 50 young people at the front of the march pressed ahead and overtook the lorry only to find they were confronted by rows of police blocking the entrance to Blackfriars Bridge. The police were determined to stop the demonstration from crossing the bridge. The bridge was symbolic. This was the first protest march since the Chartist Procession of 10 April 1848 to attempt to cross Blackfriars Bridge and the police were determined to block it. As a result, fighting broke out as the youth struggled to break through the police lines and fought to free comrades arrested by the police. “. . . Runners amongst the stewards were despatched to bring forward the truck trapped way back from the pitched battle. Chaos was increased as contradictory directives were issued by the police commanders. As Lewisham police tried to ease a way for the truck to move forward, the City police continued with blocking manoeuvres. The impasse was broken as the truck nosed its way through the seething mass, Rasta flag flying aloft. Strengthened now by the presence of the lorry, the crowd with one last heave laid siege to the police line, and with a resounding cheer, broke through the cordon.”

Among those arrested during the melee by police officers who called him a ‘ cunt ’ and ‘ bastard ’ was the Policy Studies Institute undercover researcher who was writing a police-funded study of young black attitudes towards the police….!

“We come across Blackfriars Bridge. No demonstration had crossed that bridge since the Chartists and, suddenly, the police threw a cordon across the road and say, “You are not going anywhere.” And the driver of that huge wagon, I said, “Drive!” Just leant towards him. “Drive that.” Brrrrm! And the police . . . “What? Are you going to stand before a truck?” I don’t know any police officer that brave. And we crossed the bridge into Fleet Street, running…” (Howe)

Once they had crossed the Thames, the protestors regrouped and continued their demonstration through the City and into Fleet Street. Marching in tight formation past the Red Tops and broadsheets, the protestors offered up the cries of ‘ Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said ’ and ‘ Fleet Street Liars ’. All the participant accounts concur in reporting abuse that the marchers received from the offices in Fleet Street.

“And then as we came up Fleet Street there, the taunting and the abuse that rained down upon us from the Express building in particular, I will never forget that.” (Paul Boateng)

As they passed by The Sun‘s offices ‘ there was a torrent of racial abuse from people working in the building . . . “ Go Back Home you Black Bastards ” , the usual banal kind of things that these people say ’… people leaning out of windows making ‘ monkey noises ’ and throwing banana skins at the crowd.

Against the chants of ‘ Justice, Justice ’ and the jeers of journalists, Fleet Street also saw renewed confrontation between the protestors and the police.

“In Fleet Street the whole mood of policing changed. The police imposed themselves on marchers, pushing, shoving, and kicking people off pavements. Scuffles broke out up and down Fleet Street, and, unlike Peckham, it was the police and not the stewards who stood guard in front of shops.”

In an isolated incident, which the vast majority of protesters were oblivious to, one small group broke off from the demonstration to smash and loot a jeweller’s shop. As police tried to stop them, an officer was injured. Obviously this was the incident that dominated the newspapers the next day. Despite the aggressive police tactics, of the thousands who marched that day, only 25 were nicked and charged with minor offences by the police.

There continued to be clashes and altercations with the police for the remainder of the march. Police rode horses into families with young children at Cumberland Gate in an apparent attempt to break up the march and stop it reaching Hyde Park.

Notwithstanding the provocative methods used to police the march, it did finally reach its destination at Hyde Park 7 hours aft er it had set out from Fordham Park. Thousands of protestors gathered around the lorry to listen to speeches by Howe and others.

From New Cross to Hyde Park, traffic in central London was brought to a standstill. Youth fought to break through police lines at Blackfriars Bridge and the march surged into the heart of the City… ‘city gents cowered in their offices terrified at the sight of the oppressed demanding justice’. The symbols of wealth – a bank and a jeweller’s shop – ‘fell victim to a hail of bricks and stones: journalists who quite rightly are seen as siding with the racist British state got rough justice…when a youth was arrested the march came to an immediate halt shouting “Let him go!” which police were forced to do as the marchers refused to move without their captured comrade.’

The racist response of the millionaire press to the 2 March was predictable. The Sun raved of ‘a frenzied mob’. Headlines screamed ‘The Day the Blacks Ran Riot in London’.

For many on the black communities, the Day of Action felt like the birth, or rebirth, of a large-scale black people’s movement in the UK; the sense of strength it gave people in the midst of the horror and tragedy of the fire help cement community and political unity of a kind…

If many first generation West Indians who moved to the UK responded to the racism, police attacks, discrimination, they faced by trying to keep their heads down, not making a fuss, putting up with, (if not completely accepting as fair) shit jobs, overcrowded housing and constant abuse, hoping it would gradually disappear over time. (This is not true of all, witness the self defence organised in 1958 against racist rioters in Notting Hill.) As their children grew up, however, a new angrier attitude evolved.

“Those of us who came here in the late 50s and early 60s were constrained by the myth that we were going home sooner or later, that we would earn some money and go, and therefore tended to put up with things that we knew were wrong – but there are young blacks who were born here, who have grown up here, who eat bangers and mash, egg and chips” (Darcus Howe)

This generation reacted to police oppression with a completely different attitude: this was their home, they had little intention of “returning” to islands they barely knew if at all, and were determined to make space for themselves in Britain; to force institutions and society to respect black people and their rights.

“British rulers had maintained that young blacks, who were born here or grew up here, would follow the social pattern laid down for their parents. Young blacks, they hoped, would meekly accept those jobs that refused to do; they would bow, bend before and make accommodations with their employers; they would be hesitant and cautious in their opposition to police malpractice. Undoubtedly some did, but the major tendency among the youth was a rejection, a total and militant rejection to these established ways of immigrant life.” (Race Today, 1982)

The feeling of a growing widespread resistance to racism, both organised and unofficial, murderous and repressive or simply daily harassment, was amplified five weeks later when Brixton erupted into uprising in response to years of racist policing and in particular Operation Swamp ’81.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Postscript: Inquests into the Fire

The New Cross Massacre Action Committee closely monitored the Inquest proceedings, which began at County Hall in London on 21 Apr 1981. Four theories were advanced from the police: 1) a firebomb attack from outside the building; 2) an opportunist arson attack from outside the building; 3) a deliberate fire from inside the building; 4) an accidental fire from inside the building. However, it was soon clear that racial motives were being ruled out as theories 1 and 2 were abandoned, despite the revelation from forensics that a possible incendiary device had been found at the scene. The speed and force of the fire had also caused a police officer at the scene to conclude that a petrol bomb had been thrown into the house, but this theory was dismissed. The Coroner, Dr. Arthur Gordon Davies, refused to take any notes of evidence during the hearing, preferring to read from police statements. The jury returned an open verdict.

Families with the support of the NCMAC appealed for the inquest verdict to be quashed and demanded a new inquest, considering the hearing to have been biased. The fact that the Coroner refused to take notes during the hearing was ruled illegal under Section 6 of the Coroner’s Act 1887, and the Attorney General authorised the Appeal lodged by the relatives of the dead. The integrity of the initial investigation was also called into question. On 10 May 1982, the relatives won leave to Appeal, and an Appeal date was set for 5 July 1982. However, the inquest jury refused to quash the open verdict. Despite attempts by the courts to avoid a second inquest, the NCMAC and relatives of the victims demanded that a new inquest should take place.

An International Commission of Inquiry was also planned by the NCMAC, although it never took place. In an unfortunate decision, the Courts decided to hear the Appeal during the same period planned for the International Commission of Inquiry. The latter had already been postponed from Jan 1982 due to the unavailability of some of the Commissioners chosen. In Jun 1983, the NCMAC was at last planning to hold its own independent inquiry, but decided to postpone it again after detectives suggested that they might be on the verge of a breakthrough. This subsequently turned out to be misleading.

The Committee also established a Fire Fund to support the families involved, to raise money to help families to bury their dead, and to care for the injured. The fund was chaired by Alex Pascall, member of NCMAC, and broadcaster of the daily Black Londoners BBC Radio London programme. Access to broadcasting proved invaluable for interviewing relatives and members of the NCMAC, reporting on the New Cross Massacre Campaign, encouraging public support, and analysing social and political tensions. A total of £27,000 was raised.

Annual vigils and memorial services continued to be held on the anniversary of the fire. The New Cross Memorial Trust was also set up in 1981 by the families of the victims. Following a request from black community leader Sybil Phoenix, Lewisham council erected a memorial to the victims of the New Cross fire in 1997.

Despite repeated requests, the opportunity for a second inquest did not come until 1997, when the police re-opened the investigation. Calls for a new inquest were twice rejected, until the High Court finally agreed in 2002. A second Inquest began in Feb 2004, 23 years after the New Cross fire occurred. An open verdict was again returned.

Despite repeated requests, the opportunity for a second inquest did not come until 1997, when the police re-opened the investigation. Calls for a new inquest were twice rejected, until the High Court finally agreed in 2002. A second Inquest began in Feb 2004, 23 years after the New Cross fire occurred. An open verdict was again returned.

Leave a comment