Wanstead Flats is the southernmost portion of Epping Forest in Wanstead, East London. Epping Forest itself is a a remnant of the once extensive Forest of Essex, also encompassing Waltham Forest and Hainault Forest.

On July 8th 1871, thousands of locals and people from the wider East End gathered to protest at the enclosure of the Flats, and destroyed the fences that had been put up around the land.

Historically the Flats were part of the royal forest – however, the proximity of this space to villages led people to turn out cattle and other animals to graze upon the unenclosed land. Over the centuries, this custom became tradition and was eventually recognised and granted as a right of common pasture. (Certain landowners and occupiers still have this right, granted them as part of the Epping Forest Act 1878, and cattle grazed freely until 1996 when the BSE crisis forced their removal).

Parts of Epping Forest were enclosed as parkland with large houses, which evolved from medieval manor houses. The most significant of these are Wanstead Park, dating from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth century, and the eighteenth-century Copped Hall.

As part of the Royal Forest of Essex, Epping Forest was one of sixty forests across England where Forest Law gave the Crown the right to hunt game across largely privately owned land. Hunting across forest landscapes was an important demonstration of Royal and aristocratic power and a necessary practice for war. Forest Laws recognised the earlier tradition of shared ‘common’ rights for forest dwellers to graze livestock and to cut firewood and turf.

Changing Royal interests and the rise of a professional army during the Georgian period saw Royal participation in hunting and the power of Forest Law dramatically decline. Parliamentary scrutiny of Royal finances following the Restoration saw the Royal Forest hunting rights across private land, known as Forestal Rights, begin to be sold.

From 1817, a series of Parliamentary Bills unsuccessfully pressed for the disafforestation of Epping Forest. In 1851, following the sale of Forestal Rights, 3,000 acres of nearby Hainault Forest, another fragment of the Forest of Essex, was felled within six weeks. Six years later, the Commissioners sold half of the Royal Forestal Rights at Epping Forest, encouraging the illegal enclosure of some 4,000 acres of Epping Forest by 1865.

Local people’s long use of Wanstead Flats, and its general reputation common land, led to a strong attachment to the land there. This led to resistance when attempts were made to enclose or build on parts of the land.

There was deep resentment when Lord Mornington enclosed 34 acres in 1851-2.

In the 1850s Isaac Lake was a tenant farmer of Lord Wellesley on Aldersbrook part of the Flats. Wellseley, (Lord Mornington, nephew of the famous Duke of Wellington), the Lord of the Manor of Aldersbrook, ordered Lake to enclose 34 acres of land on the Flats.

Wellesley’s plan was to build a permanent cattle market on the Flats (to replace the huge open air cattle market which was held on this area of the Flats every spring until the mid 19th century… Cattle would be driven from East Anglia and other parts of England to supply the growing London market for meat. The cattle were bought and sold in “The Rabbits” pub on Romford Road (at the corner of Rabbits Road – the building is now a pharmacy).

The enclosure provoked a local outcry: one local farmer apparently drove his cattle onto the enclosed land, breaking down the fences, and was prosecuted.

The plan to build the market failed, and the market was built in Caledonian Road, Islington, instead. Lord Mornington died in ‘humble lodgings’ in 1857, so perhaps the scheme was a desperate attempt to restore dwindling family finances…

However, the 34 acres seem to have been fenced off and built on, despite an attempt by residents of Cann Hall and other commoners attempting to block him in the courts. This seems to have involved support from Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, of the quaker brewing family, who was later to take an active part in fighting other enclosures in Epping Forest…

The most famous episode in local defence of the Flats took place in July 1871, after Earl Cowley, cousin and heir of Lord Mornington, enclosed 20 acres of wasteland, (the last piece of unenclosed land in the Manor of Aldersbrook).

Fences were erected from Bushwood to Ridley Road by Earl Cowley’s agents.

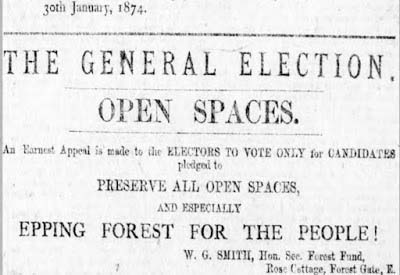

But there was an angry response. An advertisement with the headlines “Save The Forest” encouraged working people to “Attend by Thousands” an open air meeting on Wanstead Flats on Saturday, July 8th 1871 to “Protest against the Enclosures”. The meeting took place, not initially on Wanstead Flats, where the Essex Volunteers were undertaking a review, but in the grounds of a building then called West Ham Hall.

So many people attended, estimated at 30,000 – so many that the meeting was by popular acclaim adjourned to Wanstead Flats after all, with some thousands of people making their way there. The meeting would end with crowds pulling down the enclosure fences.

Here follow some contemporary accounts of the demonstration and direct action:

“THE recent destruction of the fences surrounding one of the obnoxious enclosures on Wanstead Flats may have been an act of great imprudence, but it serves to illustrate the angry spirit with which the East Londoners are beginning to regard the continual encroachments which are rapidly depriving them of the broad open spaces to the free use of which they have been accustomed for so many generations. Perhaps there is no portion of the Metropolitan suburbs so largely frequented during holiday-time as are the yet unenclosed portions of Epping Forest lying nearest to the overcrowded districts of Whitechapel and Bethnal Green. On a fine Sunday evening thousands of working men, attended by their sweethearts or wives and families, may be seen proceeding along the Mile End Road in the direction of Wanstead Flats, a large open space, perfectly level and covered with verdure, close to the Forest Gate Station of the Great Eastern Railway. The distance from London is not great, the Flats being within five miles of the Royal Exchange, a circumstance adding considerably to the value of this portion of Epping Forest as a popular open-air resort. But it is on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons during the fine days of summer, that the Flats present their most interesting appearance, for on these occasions they form the playground of immense numbers of children from the myriad courts and lanes of Spitalfields, Shoreditch, and other densely populated districts in East London. No sight can be mare touching than that of the crowds of poorly attired little ones, some of them mere toddlers, who have dragged their limbs hither, regardless of hat stony pavements and dusty roads that they might have a few hours’ romping on the soft grass or load themselves with bundles of buttercups and daisies. It is no exaggeration to say that but for Wanstead Flats, and other open spaces near East London, the late terrible visitation of cholera, which decimated so many artisan families, would have been far more destructive in its results. But the pure, fresh air of Wanstead Flats did much to counteract the unwholesome influences of the fever-reeking atmosphere which still, despite every effort on the part of the sanitary authorities, too often pervades the humble homes of the East London labouring poor. But the Flats are apparently doomed. Earl Cowley’s enclosure is by no means the first of its kind; there, have been several others such as that, the fences of which have just been destroyed. Before Mr. Gladstone promised to take up the question of Epping Forest, the Crown rights over Wanstead Flats had been sold for 12,000l. by the Commissioners of Woods and Forests. Nothing but the rights of the commoners remain, and these have been disregarded because there were none sufficiently wealthy to defend them. But the Corporation of the City of London having recently, through their purchases of land for their cemetery at Ilford, become possessed of the rights of common an Wanstead Flats, have announced their determination to defend the same at whatever coat. This is the first time that the system of enclosure has experienced any real check. Should the Corporation gain the day, the free use of Wanstead Flats will have become secured to the East Londoners; but the conflict will be a long and costly one, for the encroachers instinctively scent the danger which awaits them, that they may not only be prevented from making further enclosures, but, also be compelled to give up some of the land of which they have been too easily allowed to acquire possession.“ (The Weekly Graphic, 15 July 1871)

“A meeting to protest against this filching of the forest was held, on Wanstead Flats last Saturday. The people v. lords of manors; the people v. Chancellors of the Exchequer who decline to protect them: the people’s rights against all would confiscate them – formed the key-note of every speech. Let it be understood at once that as far as the proceedings at the meeting proper were concerned there was no violence. The powerful force of policemen, both horse and foot, which had been sent down to guard Lord Cowley’s obnoxious fence had nothing to do; and a large majority of the gallant fellows whiled away the calm summer evening by foot-races, jumpings, and athletic sports upon land which is still common. Others were placed on duty within the various doubtful inclosures, and others, again, hovered round the public meetings, of which there were several held upon the Flats.

WANSTEAD FLATS, it may be explained is the title of the portion of Epping Forest which is nearest to London, and is but a stones throw from the Forest-gate station of the Eastern Counties Railway, and some quarter of an hour’s walk from as crowded and busy thoroughfares as there are in the metropolis. The meeting of Saturday had been announced beforehand, and the possibility of lord Cowley’s new fence being removed “by resolution” had been not obscurely hinted at. A review of volunteers had been announced to take place on Wanstead Flats at the hour at which the chair was to be taken, so placards were issued that “in consequence of this, Lord Cowley’s last inclosure would be discussed in a field adjoining West Ham Hall, the residence of Mr. Tanner. This was not far from the Flats, but it was too far for the meeting. An amendment was moved the moment Sir Antonio Brady took the chair. Mr. Wingfield Baker M.P., advised and pleaded in vain.

“To the flats!”

“They’re oar own.”

“Wy should we be pravented meeting there?”

“Wot is there to be afraid of?

“Whose fault is it we have to meet at all?”

“Wot about Berkhampstead?” [This refers to the then recent and highly publicised case of Lord Brownlow’s attempt to enclose Berkhamstead Common, which had ended with his fences being removed by night, after the enclosure was contested legally].

“Where’s Lord Brownlow’s palings now?” – came from scores of lusty voices and when the amendment was put “that this meeting do adjourn,” a perfect forest of hands was held up in its favour.”

“The committee under whose auspices the meeting had been convened were seated in a large waggon which had been fitted up with tables and chairs, and two or three other vehicles of a like character stood around, all crowded, and all without horses. What so fitting as that they should be dragged on to the Flats by the enthusiastic crowd? There was plenty of superfluous energy about, and a dozen willing fellows had harnessed themselves, and waggons, committee, chairs, tables, and paraphernalia were out of the field and jogging along the road at a steady trot in far less time than it has taken to read these lines. At the meeting there was plenty of good vigorous oratory; but it is not necessary to follow the speakers very closely. Resolutions were passed that an address shall be presented to her Majesty; that the Government shall be urged to pass a short bill this session to effectually prevent further inclosures; that thanks shall be rendered to the Corporation of the City of London ; and that copies of these resolutions shall be sent to the Prime Minister, to the chancellor of the Exchequer (loud and prolonged groaning followed every mention of Mr. Lowe’s name), and to every member of Parliament whose constituents are immediately interested in the preservation of the forest What was specially significant was the tact and temper displayed by the speakers and the plain influence of those qualities over the crowd. Strong as the police force was, it would have availed but little against the stalwart fellows who had just drawn in heavy waggons laden with heavy gentlemen over roads and turf, and had enjoyed the gentle exercise that proceeding gave then. A little swaying to and fro, a slight pressure in one direction – nay, a passive yielding to circumstances such as governs innocent spirit-rappers and table-turners who have a predisposition to believe – and the nearest paling would have fallen like a house of cards. But from first to last those present were adjured to give their enemies to handle against them. So the great demonstration began, continued, and ended peacefully. Earl Cowley’s fence remained intact when the meeting separated, and the extra police force were dispersed after nothing more stirring than a few hours pleasant pastime in country air.” (the Penny Illustrated Paper, 15th July 1871)

The Committee who had called the meeting were alarmed by the strength of the feeling. Fearful of the increasingly vocal calls for destruction of the fences on the Flats, they had tried to persuade the crowd not to march on the Flats… But the demonstrators were having none of it. As soon as the first speaker began, there was a storm of hissing, and shouts of ‘to the Flats’, followed by the manhandling of the carts, from which the gentleman leaders were speaking, up Chestnut Avenue and onto the Flats.

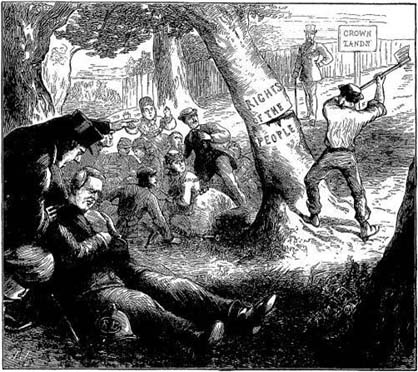

The official meeting on the Flats agreed to petition the Queen over the forest enclosures, then the leaders left, as did the large police detachment sent to guard the fences. Everything seemed to have passed off peacefully, but later that evening the mood changed. Very quickly, hundreds of yards of fence were reduced to matchwood:

“THE DESTRUCTION OF FENCES happened later in the evening. Close to nine o’clock an incident occurred which changed the whole aspect of affairs, and the fence around the inclosure at the side of the Flats near the Foresters’ Arms, and quite close to whore the meeting had been held, was destroyed in the twinkling of an eye. A man, while seated on a rail of the fence, was asked by a comrade to go home; he demurred, and his friend pulled at him to make him get down; the rail shook and in a moment half a dozen hands brought it to the ground. A dozen hands laid hold of the next; it gave way; in a minute there were fifty persons pulling energetically, then a hundred, then hundreds. The sound of the breaking up of the railing – for they were smashed into fragments as they were got from the posts – sounded like a continuation of the file-firing of the volunteers, and hundreds of people rushed up from all parts of the Flats and from the side roads and public-houses. In five minutes the fence around the inclosure was almost wholly destroyed.

A solitary constable galloped along the Ilford road after the police, and brought back at full speed fifteen or twenty mounted men, who rode on to the Flats. As no one was to be seen engaged in any overt act they could do nothing. In a few minutes the foot-police rushed back at the double, and were unmercifully “chaffed” by the crowd, who recommended them to take care of the fragments of the railings. In a moment a small body of working men, at a remote part of the inclosure, essayed to destroy a few rails still standing. The mounted officers leaped their horses over the remains of the fence and rode straight it the destroyers, who fled precipitately. One young man was apparently ridden down by an inspector, and while on the ground a body of the foot police laid hold of him. The crowd turned back, and, saying “they mustn’t have him!” attempted to rescue him. This movement was soon put a stop to by the very energetic efforts of the small body of horseman, who charged about on all sides. The prisoner was handcuffed and marched off, the crowd following him with the intention of rescuing him in this narrow road; the police frustrated this by suddenly drawing a line across the road and charging the mob coming along. In the melee that ensued some minutes were occupied, which gave time to a party of police to hurry the prisoner along the Ilford road and effectually secure him. In addition to the man then made prisoner, the police captured a boy, whom they also carried off in custody…” (the Penny Illustrated Paper, 15th July 1871)

The man arrested was a Whitechapel cabinetmaker named Henry Rennie. A pitched battle then took place, as the crowd tried unsuccessfully to rescue him. He was later prosecuted, and he was fined 5/- (25p – a fair sum for a working man then), which was paid for him by one of the Forest Gate organisers of the meeting.

“The police were utterly taken by surprise by what occurred. They were expecting something of the kind with regard to Lord Cowley’s fence at the other end of the fence adjacent to the Ilford Cemetery, and had a pretty strong force in reserve there. On Sunday they remained on guard. On Monday, also, they held their ground, it having been rumoured that some persons had determined to try the right of way by passing through Lord Cowley’s inclosure. the leaders, however, were not on the spot, and the rain, descending, dispersed the people who had gathered in expectation of another demonstration.” (the Penny Illustrated paper, 15th July 1871)

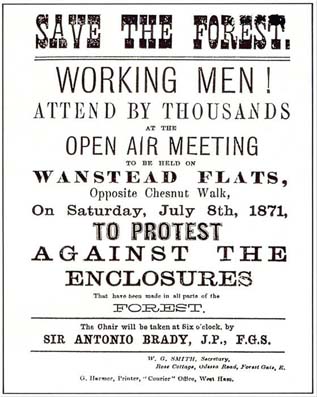

The demonstration attracted nationwide news coverage, much of it highly critical of the government. A few days later the Prime Minister, William Gladstone, came to view the Flats, after which his administration rushed through the first of a series of acts on Epping Forest, prohibiting further enclosures while a Commission investigated.

In the following month the Corporation of London, concerned at the pace of enclosures in Epping Forest, started proceedings against all the Lords of local manors who had enclosed land.

However, the campaign was just getting going. A pressure group called the Forest Fund, was established in Forest Gate, with local residents such as Charles Tanner, owner of West Ham Hall, forming a key part of the committee. The secretary was William George Smith, a County Court Clerk who lived in Odessa Road, Cann Hall. Smith played a major role in the popular campaign for Epping Forest, working tirelessly over the next few years, organising petitions to parliament from east London vestries (the main units of local government before Councils) and lobbying MPs and voters during elections.

In 1872 the Forest Fund organised a second demonstration on Wanstead Flats, timed to coincide with a further parliamentary debate on the future of Epping Forest. By this time the City of London Corporation had entered the fray, using their rights as Epping Forest commoners to bring legal action against the Lords of the Manor in the forest to stop enclosures. In doing so the City was seizing an opportunity to win popular support among Londoners. London’s government was increasingly seen as outdated for a modern city, and the City of London represented for many an undemocratic and unaccountable elite.

From 1875, the Corporation of London negotiated purchase of land from all the manors of Epping Forest; and enclosed land was reopened for all, including Wanstead Flats. The events at Wanstead and the previous action of Tom Willingale at Baldwins Hill had prompted this – we will return to Tom Willingale in November…

A combination of the Corporation’s legal action and parliamentary action by radical London MPs finally led to the Epping Forest Act passed 140 years ago. But it was direct action by East Londoners that was the crucial spur…

One reason why the Flats attracted so much support was their popularity with Eastenders for recreation. The East End having a huge working class population with few gardens and a shortage of open space, Wanstead Flats and Epping Forest were often crowded with people looking to escape the crowded dirty city for a few hours. Festivals and fairs were often held there, as Arthur Morrison recalled:

“WHIT MONDAY ON WANSTEAD FLATS

There is no other fair like Whit Monday’s on Wanstead Flats. Here is a square mile or more of open land where you may howl at large; here is no danger of losing yourself as in Epping Forest; the public-houses are always with you; shows, shies, swings, merry-go-rounds, fried fish stalls, donkeys are packed closer than on Hampstead Heath; the ladies’ tormentors are larger, and their contents smell worse than at any other fair. Also, you may be drunk and disorderly without being locked up – for the stations won’t hold everybody – and when all else has palled, you may set fire to the turf.” (Arthur Morrison, Tales of Mean Streets, 1895.)

Twenty years after the direct action which saved the Flats were also the venue for a ‘free speech fight’, as anarchists holding open air public meetings there were targeted by police and local press.

In 1946-7, the Flats were also threatened, as plans to build on them to house thousands of eastenders displaced by WW2 bombing were drawn up. Protests against the plans forced them to be shelved (we will come back to this later this year…

… and Take Back Wanstead Flats campaigned against the temporary building of police operations bases for the run-up to and duration of the 2012 Olympics… photos here

Leave a comment