No Through Road?

This is a brief introduction to some of the social engineering involved in the building of three new roads in London in the mid to late 19th century, exploring the areas destroyed to establish these streets and some of the motivations behind their creation. It is far from comprehensive and only concerns specific examples. However, much of the thinking, ideologies, geography and practice discussed here have been and are being applied to myriad other neighbourhoods throughout the world, certainly at that time, but more and more in the century and a half since. It is a work in progress of sorts… And calls up experiences we have had in our own lives much more recently.

In an early act of development as social engineering, New Oxford Street, in London’s West End, was built between 1844 and 1847, partly to break up the St Giles rookery, a notorious slum, by demolishing some of its most notorious alleys and tenements. Many such schemes to improve London’s main roads were also deliberately used in the 19th Century, to clear areas of poverty and lawlessness the authorities found threatening and troublesome. Part of the impulse behind these plans came from moral campaigns to reform people considered to be to some extent responsible for their poverty and criminality, or failing that, to disperse them and shift them elsewhere.

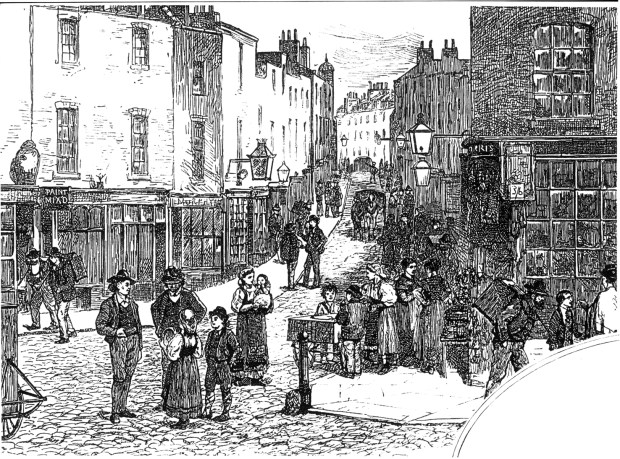

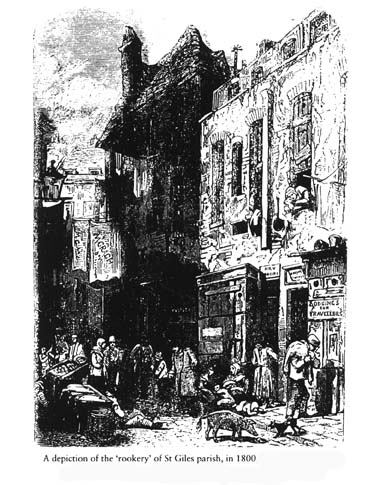

The area that was demolished for the building of New Oxford Street was the heart of the St Giles Rookery, for centuries probably central London’s most notorious slum, considered a cesspit of humanity, a harbour for rebels & criminals: “ one dense mass of houses, through which curved narrow tortuous lanes, from which again diverged close courts… The lanes were thronged with loiterers, and stagnant gutters, and piles of garbage and filth infested the air.” (John Timbs, Curiosities of London).

Largely contained between Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury Street (then Charlotte St) Broad Street and St Giles High Street, the rookery was known for the poverty of its residents already by the end of the sixteenth century (when the area was fairly recently built up). The character of this part of the parish of St Giles generally declined through the eighteenth. Once a “most wealthy and populous parish”, the huge social upheavals in Tudor and Stuart times saw a massive increase in people uprooting and moving, usually from the countryside into towns and cities. Poor folk coming to London to seek work seems to have first led St Giles to its notoriety as a nexus of the unruly poor; this influx of people with no settled place to live or job worried the authorities and the well-to-do, who feared the instability, crime and financial burdens of supporting them on the local parish. Attempts were made in St Giles (and widely elsewhere) to control the migration of undesirables into the parish: in 1637 it was ordered that, “to prevent the great influx of poor people into this parish, the beadles do present every fortnight, on the Sunday, the names of all new-comers, under-setters, inmates, divided tenements, persons that have families in cellars, and other abuses.”

But as those who could afford to move gradually drifted west to newer, more prosperous estates, the houses they left became subdivided and sublet and relet, often on short leases, creating complex patterns of ownership that made repairs and maintenance a logistical nightmare and defeated authorities’ efforts to enforce legal standards. The inhabitants became poorer and overcrowding rocketed. the late 1700s, the parish was “said to furnish his Majesty’s plantations in America with more souls than all the rest of the kingdom besides.” (ie large numbers of St Giles residents were sentenced to be transported to the penal colonies) and for producing a disproportionate percentage of those who hanged at Tyburn (as well as several of the “Jack Ketches”, the public hangmen who “turned them off”) The inhabitants of the rookery were called “A noisy and riotous lot, fond of street brawls, equally ‘fat, ragged and saucy…”

The most notorious streets were Jones Court and Bainbridge Street, according to Mayhew: “some of the most intricate and dangerous places in this low locality.”, a haunt of coiners and thieves, costermongers (pedlars and street hawkers) , fish-women, news-criers, and corn-cutters. A bull terrier was said to stand at the corner of these streets, trained to bark if a stranger approached; it was later taken away by the constables and destroyed. Jones Court, Bainbridge Street and Buckeridge Street were joined together by cellars, roofs yards and sewers, making it easy for fugitives to escape any authorities who came in to arrest them; these warrens were filled with booby traps – for example hidden cess pools. Also infamous was Carrier Street (which ran north to south in the rookery): Mother Dowling’s lodging house & provision shop stood here, frequented by vagrants of every sort. Cellars became so integral a part of life here that ‘a cellar in St. Giles’s’ became a byword for living in extreme poverty.

The rookery mostly consisted of a warren of cheap lodging houses, “set apart for the reception of idle persons and vagabonds.”, where accommodation could be found for twopence a night:

“there was, at least, a floating population of 1,000 persons who had no fixed residence, and who hired their beds for the night in houses fitted up for the purpose. Some of these houses had each fifty beds, if such a term can be applied to the wretched materials on which their occupants reposed; the usual price was sixpence for a whole bed, or fourpence for half a one; and behind some of the houses there were cribs littered with straw, where the wretched might sleep for threepence. In one of the houses seventeen persons have been found sleeping in the same room, and these consisting of men and their wives, single men, single women, and children. Several houses frequently belonged to one person, and more than one lodging-house-keeper amassed a handsome fortune by the mendicants of St. Giles’s and Bloomsbury. The furniture of the houses was of the most wretched description, and no persons but those sunk in vice, or draining the cup of misery to its very dregs, could frequent them. In some of the lodging-houses breakfast was supplied to the lodgers, and such was the avarice of the keeper, that the very loaves were made of a diminutive size in order to increase his profits.”

Notorious pubs were prominent: the Maidenhead Inn, the Rats Castle, the Turks Head, all in Dyott Street, and the Black Horse, each said by outraged commentators to be the HQ of gangs of beggars, thieves and pickpockets.

Of the Rat’s Castle, the Rev. T. Beames, in his ‘Rookeries of London,’ (a classic outraged ‘expose’ of life in the slums) said: “In the ground floor was a large room, appropriated to the general entertainment of all comers; in the first floor, a free-and-easy, where dancing and singing went on during the greater part of the night, suppers were laid, and the luxuries which tempt to intoxication freely displayed. The frequenters of this place were bound together by a common tie, and they spoke openly of incidents which they had long since ceased to blush at, but which hardened habits of crime alone could teach them to avow.” Gin shops also abounded, at a time when the half-raw, dirt cheap spirit was the cheapest and quickest way to drink away your troubles: one in four houses in St Giles was estimated to be selling spirits in 1750.

The area contained a large poor Irish population, said to be three quarters of the population in some streets, so much that it was nicknamed little Dublin, or the Holy Land. They gradually displaced older groups like French Hugenots who had moved here in the 1680s. Most of the Irish were labourers, originally arriving to work the harvests, later flocking to the building and brewing trades. In 1780, the majority of the 20,000 odd Irish people living in London were residents of St Giles. Besides the irish, by the 1730s this area also housed a noticeable black community, known as ‘the St Giles Blackbirds’, many ex-slaves, some on the run from their ‘owners’, some former sailors or ex-servants.

Rookeries inspired great fear in the middle and upper classes. At the most basic level the idea of thousands of the poor, swelling together, desperate, with little to lose, always a threat to peace and social order even as individuals, liable to commit crime against their betters, spread disease…

Rookeries inspired great fear in the middle and upper classes. At the most basic level the idea of thousands of the poor, swelling together, desperate, with little to lose, always a threat to peace and social order even as individuals, liable to commit crime against their betters, spread disease…

The way the rookeries are described in contemporary writing exposes the kind of threat they saw in them. Well-to-do commentators saw the rookery through a lens tinted with their own prejudices, but always the view is from the outside, looking in, uncomprehending, totally without experience of the lives lived within.

Sometimes they are compared to forests, wild, scary impenetrable places with hidden dangers, as does writer and magistrate Henry Fielding: “Whoever… considers the cities of London and Westminster with the late vast addition of their suburbs, the great irregularity of their buildings, the immense number of lanes, alleys, courts, and bye-places; must think, that, had they been intended for the very purpose of concealment, they could scarce have been better contrived. Upon such a view the whole appears as a vast wood or forest, in which a thief may harbor with as much security as wild beasts do in the deserts…”

There are interesting echoes here, and in other 18th and 19th century writings about slums, of earlier perceptions, writings and fears – about forests and wild woods, and the people who sheltered there. From Robin Hood to disaffected levellers and fifth monarchists, woods were viewed in a similar way, as dangerous, almost impenetrable dark fastnesses, hiding wild beasts and even wilder people – outlaws, rebels, runaways and outsiders (likely to include gender & sexual non-conformists, certainly including escaped servants, serfs and slaves). Fairy tales and folklore reflects this, abounding with a fear of the deep dark woods. In the 16th and 17th centuries rookeries begin to replace forests as the main focus of such fears, as enclosure/agricultural change was increasingly taming and regulating the wilder aspects of countryside and forest.

Alternatively, rookeries and city slums were compared to insect or animal colonies: John Timbs described St Giles as “one great mass, as if the houses had originally been one block of stone eaten by slugs into small chambers and connecting passages.” The very language dehumanises the inhabitants, labelling them basically slugs, termites or other insects; a dehumanisation of the poor that is a regular feature of observations on the lower classes by the better off. (There are fewer verminous metaphors used to describe landlords or middlemen, often ‘house-farmers’ leasing from the rich and making tidy sums from subdividing the garrets, who benefitted from overcrowding their houses for their own profit.)

In comparing slum dwellers to wild beasts, using metaphors like the slug reference, onlookers are suggesting the beasts have moved to the city. And similar reforming and reshaping urges would be used to control this: like enclosure, demolishing rookeries and building new roads was both profitable, and a taming of disorderly space… bringing order to chaos and inefficiency; light into darkness.

Other commentators used medical analogies, seeing the slums as diseased or unhealthy body parts or organs, needing surgical removal. Architect Sydney Smirke described the city as suffering from “Corruption, stagnation, lack of communication, and the ‘noxious miasmata’ of disease” which required the scalpel of demolition, “the ‘very beneficial purgation’ that ‘a perfect symmetry’ would bring.” The ‘rotten core’ of London would be ‘cut out’. Disease was very much on London’s collective mind: Smirke was writing just two years after the first cholera epidemic, which had seen thousands die, often in the poorest areas, from drinking contaminated water, though this was not generally recognised until years later.

London’s streets were often also described as being maze-like, tangled and dark – difficult or impossible for strangers to navigate through (to read how common the comparison with the labyrinth was, check out this great article). The labyrinth from classical mythology seemed an obvious parallel for middle class commentators, given the inevitable reminder of the minotaur, the dark and wild beast lurking at the centre of the maze, part animal part man… A perfect analogy for the criminal poor, destitute and violent, the subhuman creatures who the writers saw as inhabiting the rookeries… As much as the invention of the Victorian respectable fear-mind as the minotaur was of the ancient greek mythologist.

Victorian writers saw and depicted much of slum London in terms of dirt – but linked this to immorality and transgression.

“Middle-class observers saw the urban environment that created impenetrable spaces as creating the conditions for the transgression of social boundaries through the bringing into greater proximity of different classes. The great metropolis and the industrial towns of Britain were in fact dirty, as human waste piled up in cesspools, soaked into the soil and flowed into the rivers. The filth of the city, and people who worked around it and on the streets, created classes of people who were a dangerous and volatile Other to the domestic middle class.” (Strange Bodies and Familiar Spaces: WJR Simpson and the threat of disease in Calcutta and the tropical city, 1880-1910, A Cameron-Smith)

Mid-late nineteenth century writing, from sensationalist journalism to the ‘urban exploration’ of social reformers like WT Stead or Charles Booth, teems with filthy houses and streets, stagnant, overcrowded, labyrinthine courts and rooms. These environments are causably linked to the immorality and dire poverty of their inhabitants; though sometimes the environment, the ‘dirty houses’ themselves, are blamed for the condition of their residents, and sometimes it was vice versa. As Erika Kvistad points out, the obsession with dirt and darkness grew to the point where demolition of the slums came to represent a sort of exorcism of the threat from these areas:

“dirt was the point where scientifically driven social activism and superstitious horror met. They imagined poor homes as “bad property”, both the location and the source of moral uncleanness. The by then disproved miasma theory of disease persists in these texts both as a fact and as a persuasive metaphor. It allowed urban exploration writers to articulate both the fear of the squalid dwellings where poverty, disease and moral decay arise, and the fear that this badness might spread through the wealthier parts of the city. In this way, the demolition of filthy homes functioned not only as a social project, but as a form of exorcism… in many of the central texts of late-Victorian urban exploration writing, the obvious social problems that beset the poor areas of British cities, like inadequate housing, crime, and the spread of disease, become linked with the idea of certain living spaces as intrinsically bad.” (Erika Kvistad, Bad Property: Unclean Houses in Victorian City Writing, University of Oslo).

Dickens, in Dombey and Son, sums up the Victorian view of how environment infected inhabitants:

“Those who study the physical sciences, and bring them to bear upon the health of man, tell us that if the noxious particles that rise from vitiated air were palable to the sight, we should see them lowering in a dense black cloud above such haunts, and rolling slowly on to corrupt the better portions of a town. But, if the moral pestilence that rises with them, and in the eternal laws of outraged Nature, is inseparable from them, could be made discernible too, how terrible the revelation! Then should we see depravity, impiety, drunkenness, theft, murder, and long train of nameless sins against the natural affections and repulsions of man-kind, overhanging the devoted spots, and creeping on, to blight the innocent and spread contagion among the pure.”

An insanitary neighbourhood guarantees wicked and vicious residents, and this threatens to spill out to endanger the nicer folk in their clean streets.

The threat the poor posed to the rich became even more terrifying if they organised and acted collectively, either as gangs, or worse, as a mob. Outbreaks of disorder, riot and uprising were not uncommon in the 18th and 19th century. At their wildest, events like the 1780 Gordon Riots, when huge crowds latched onto a reactionary anti-catholic demonstration and launched five days of cataclysmic attacks on Parliament, London prisons, the houses of the rich, and other centres of power, scared the rich and powerful; many of those arrested and hanged were identified with London’s rookeries, seen as no go areas and centres of popular insurgency. In 1780, several Gordon Rioters were nicked in the St Giles Rookery with loot, including Charles Kent and Letitia Holland, arrested for the attack on Lord Mansfield’s house, who were apprehended in Bambridge Street.

After the French Revolution of 1789, this fear became heightened – what if the ‘mob’ could be harnessed by radicals, the violence of London’s poor allied to ideas of equality and liberty? – in Paris that had ended with aristocrats going to the guillotine.

Responses among the wealthy to this threat varied from the purely repressive, to more sophisticated thinking on social control, moral reform and alterations in urban environments to both neutralise the actual collective threat, and alter the lifestyles and ways of thinking of ‘slum dwellers’.

Some social reformers among the 19th century well to do saw slum clearance as part of the solution to this threat – this represented both a short and a long-term plan. Immediately dangerous and unhealthy slums were dispersed; in the longer term, the behaviour of the poor could be remodelled, channelled, made more law-abiding and respectable. These were broadly of the same movements and circles (and and often specifically the same individuals) that had also worked to ensure factory acts and other protection legislation was passed, as well as advocated, raised charitable funds for and helped to create the first real social housing in London – the model dwellings – and also agitated against the destruction of open space and for its transformation into parks. For many of these social reformers, this work was a conscious mix of genuine concern for the conditions the working class lived, worked, played in, and an equally genuine fear and loathing of working people and disapproval of much of their culture. The philanthropy they passionately believed in was very much tempered with paternalism – they knew best and would alter the social conditions, and would improve the morals and behaviour of the lower orders. Some of the reformers who pioneered slum clearance thought a proportion of the inhabitants could be saved, if they were removed from the disorderly environment they lived in, though others were wedded to their immoral ways and were just unredeemable.

Others of the would-be redesigners of urban space were less concerned with reforming the poor. They just wanted the most disorderly of them to go away.

By the mid-19th century, St Giles’ notoriety had made it the focus of plans to redevelop the area – with both social control and improvement in east-west road traffic movement in mind.

As early as 1836 a Parliamentary Select Committee recommended demolition of several of the rookery streets: “By pulling down the aforesaid district, a great moral good will be achieved by compelling the 5,000 wretched inhabitants to resort and disperse to various parts of the metropolis and its suburbs.” St Giles location, around one of London’s most troublesome traffic bottle-necks, and its high death rates from disease, marked it for destruction.

There’s no doubt London was almost paralysed by traffic problems by the 1830s. The huge increase in the size of the city, its population, the business being carried on, the sheer tonnage of goods and people needing to be transported, was simply not reflected in much change to the capacity of the roads to contain it all. Much of the two intertwined cities of London and Westminster was laid out broadly as it had been in medieval times; neither adequate nor suitably grand and impressive as befitted the capital of what was becoming the most powerful empire on the planet. The sheer difficulty of moving through London, either on foot or by carriage, was notorious; wagons of goods could end up bogged down in the gridlocked narrow lanes.

Previous attempts to re-organise the chaotic jumble of streets and lanes along more systematic lines (such as Christopher Wren’s proposal to rebuild the devastated City of London according to a grid and radial pattern after the 1666 Great Fire) had been frustrated by the complex web of land ownership, occupation and long-established customs and communities. Central planning was scanty and widely resisted by the rich who owned much of the city; and the building of new roads were often carried out piecemeal. Some roads were built by privately by the owners of large estates, and property disputes blocked, delayed or significantly altered the creation of new thoroughfares. (Witness the aggro that accompanied the creation of the Duke of Bedford’s road through Bloomsbury as an example…)

By the 1830s, there was pressure to remodel the city to make travel and transport of goods more efficient:

“In 1834, architect Sydney Smirke took his readers on a ride through the west central districts of London, pointing out the lack of north-south roads, and showing that 200-year-old thoroughfares were still expected to take the traffic of a population that had tripled in size. His was a serious plea for the government to set up a centralised body to plan and finance the restructuring of the city: ‘No parliamentary measure could be more truly patriotic.’

In Smirke’s analysis, London was stagnating because insufficient money was made available by Parliament for reconstruction, while private property rights were considered to be so sacred that any public-minded schemes were compromised or simply abandoned.

Straight lines should push through convoluted, congested regions, stated Smirke, as he catalogued the ‘strange irregularity’ and ‘ill-directed lines’ of London thoroughfares. The kink in the road by St Giles church was ‘very objectionable’; Clare Market was ‘populous and ill arranged [and] the best mode of improving this district would be to open a spacious avenue through the centre of it.’ Smirke wanted to “obliterate the streets of the past and create a city that reflected the new-found power, wealth and mores of an ascendant middle class: ‘By some objectors we are told to “live as our fathers have lived before us,” who, being content to jostle through crooked and devious lanes, were fain to make their fortunes in blind alleys, with the internal satisfaction that their monies contracted no offensive taint from the foetid corrupt age, according to Smirke, and this has found its physical expression in the twisted streets of that era. The nineteenth-century city must, by contrast, be ‘laid out as to be wide, clear and regular’…

Straight lines and perfect symmetry were also required by those in charge of building sewers. Henry Austin, in 1842, spoke of the need for pulling down the whole of St Giles – not just the northern part – and ‘making a straight street, instead of a crooked line, from Bow Street to Broad Street’. This would facilitate interaction between ‘quarters of the town now separated by a labyrinth of lanes and alleys’. The image here is of the old, economically unproductive regions hampering commercial progress. Austin was involved in Edwin Chadwick’s sanitary movement and was doubtless influenced in his love of straight lines by the knowledge that such streets were best-suited for carrying sewage pipes.

According to the architects and engineers, London needed to have its crooked ‘no-thoroughfares’ replaced by straight broad streets.”

(‘Labyrinthine London’: writers, social reformers and the need for more ‘ordered’ streets in the mid-Victorian metropolis, Sarah Wise)

There was also the question of regulation and control. Rookeries had grown organically, haphazardly, largely uncontrolled, over centuries, and this was reflected in both the physical space and the legal ownership of the buildings. A mass of yards, winding lanes, alleys, dead end courts, lean-tos and sheds, and cellars, on sub-divided lets, complex leases and sub-leases, with many layers of ownership and residence. This made proving responsibility for any issue of possible dispute – rent, repairs, sanitation etc – almost impossible to navigate easily (just as the space was physically hard to find your way through). If this had served in less ordered eras, by victorian times there was an explosion of regulation, of rules, regarding all sorts of areas of city life, dealing for instance with buildings, and with people. The use of statistics and records was rocketing and becoming much more systematic. A London-wide police force had been created to regularise and codify the imposition of law and order. Slums that were impassable, unknown, could not be allowed to remain so.

But rookeries were worse than unknown – they were like strongholds of the enemy, in territory that the bourgeois state and the wider bourgeoisie, where it manifested itself as a conscious class, could only see should be theirs, uncontested.

Aspects of rookery life were calculated to enrage a class that saw itself as entitled to rule, though also (to some extent) also liked to think of itself as both enlightened and interventionist.

Many slum-dwellers defied the law. A rough community solidarity against the law was a common feature of London’s rookeries. “The police only rarely went into the rookeries; and if they intended to arrest, then only in large numbers. So there usually was plenty of forewarning; sometimes large numbers of the rookery population came on to the street to confront a police invasion… Living at such close quarters to each other also imposed a certain communal structure on daily life. Eyewitness investigators noted that the rookery communities were often tight-knit and mutually supportive; amid the terrible conditions of the rookeries, still a certain commonality and solidarity bloomed… Being so autonomous from regular police presence meant that the rookery thieving community evolved a sophisticated environment to protect their trade.”

This attitude of resistance involved both social networks of self-defence against the law. But it also led to alterations and adaptations to the physical environment (already hugely useful by the rookeries’ complex maze-like structures) to make incursion by authorities very difficult (see the description of the booby traps and escape routes of Saffron Hill, below).

For the authorities and the respectable commentariat of the time, this type of physical resistance to the power of the law was an assertion of outrageous autonomy. No go areas in the capital could not be allowed to continue to exist. (In a very similar process, dismantling the no-go areas in catholic/nationalist areas of Belfast in the early 1970s, set up to defend against riotous incursions by unionist sectarians was a priority for the British Army… and autonomous street culture in inner city areas like Brixton had to be attacked by the Special Patrol Group, because the police considered this a challenge to law and order, proto-no go areas in development…)

A “new, straight and spacious street

The building of New Oxford Street was specifically the result of the 1837-38 report of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Metropolis Improvement. In discussing plans for what would eventually be New Oxford Street, this report refers to “the formation of a “new, straight and spacious street into Holborn, suited to the wants of the heavy-traffic constantly passing … provision would, at the same time, be made in a very great degree, for the important objects of health and morality”.

One of the consultant engineers for this report urged the Select Committee to follow a certain route for the road, because this would prove to ‘be the means of destroying a vast quantity of houses which are full of the very worst description of people.’

Work on New Oxford Street was begun in 1844, and the new road opened to traffic on 10th June 1845, though work wasn’t entirely completed until 1847. Several of the most infamous rookery streets disappeared during its construction, leaving some 5000 of the poor homeless; while the Duke of Bedford, owner of 104 of the demolished houses, received £114,000 in compensation (a huge sum then.) Driven from their homes, but in many cases needing to stay near their work or sources of casual labour, the rookery dwellers generally found lodgings nearby, causing a 76 per cent increase in population in some other local streets. The building of New Oxford Street, together with the later construction of nearby Shaftesbury Avenue through other notorious parts of St Giles, began the reclamation of this long-infamous area for respectability.

Not everyone was convinced of the effectiveness of demolition. Charles Dickens, for instance, was an early critic of the tactic of using road building to clear slums. He pointed out that far from reducing crime and letting in the light of ‘respectability’, the new road had only made worse all the conditions most likely to cause crime: “Thus we make our New Oxford Streets, and our other new streets, never heeding, never asking where the wretches whom we clear out, crowd … We timorously make our Nuisance Bills and Boards of Health, nonentities, and think to keep away the Wolves of Crime and Filth.”

The New Oxford Street scheme wasn’t the first proposal to remodel London in the interests of the rich and social exclusion.

One of the reasons cited in support of the proposals for the original construction of Blackfriars Bridge in the 1760s (apart from the transport and commercial advantages of new river crossings), was to help clear the lawless slums around the mouths of the river Fleet (especially the notorious Alsatia rookery) – it was thought opening up and redeveloping the area to the south would help.

In 1812, architect John Nash had reported to His Majesty’s Commissioner of Woods, Forests and Land Revenues, proposing new roads and grand vistas where a hotchpotch of roads and alleys then existed around Charing Cross, then considered the ‘hub’ of London life. For Nash, his development scheme offered the added bonus of bulldozing the Swallow Street rookery in Soho. An Act of Parliament in 1813 ensured the Nash scheme, for a major new road for the north of the capital and from the area around Haymarket and Charing Cross, would go forward. The rebuilding work went on to create great sweeping crescents, notably Regent Street, built between 1817 and 1823, designed by Nash specifically to separate the ‘Nobility and Gentry’ in their ‘streets and squares’ from the “narrow streets and meaner houses occupied by mechanics and the trading part of the community”. Nash’s new roads were organised in such a way as to ‘cut off’ access by the poor in their ghettos in St Giles, Porridge Island, Seven Dials and the mean streets near Haymarket and Westminster, restricting their direct access, making entering the posh streets west of Soho a long and tiring business. If later schemes emphasised the improvements in traffic flow and the movements of goods, the Regent Street/Charing Cross developments also had restriction of movement at their heart. Fear of the London crowds, the threat their very movement around the city inspired in the wealthy, was a major consideration in Nash’s plans. It is not insignificant that the years of its building saw a huge upsurge in the perennial movement for political reform, spiced with poverty and economic slump following the end of the 23 year war with France; the refusal of the government to even consider reform led to brutal repression as at Peterloo, to riots like the Spa Fields uprising, to plots for revolutionary insurgency and plans to assassinate the cabinet. Fears of riotous mobs and serious thinking on how to frustrate their ability to move through the city were not idle fancies.

The building of New Oxford St was, however, only the opening skirmish in a long process of architectural class restructuring, in St Giles, and wider afield in London. Other notorious London rookeries experienced major reconstruction schemes beginning in the 1840s, including Field Lane/West Street in the Saffron Hill area; parts of Spitalfields & Whitechapel removed to build Commercial Street, and the ‘Devil’s Acre’ in Westminster.

The creation of the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1855 stands out as a significant point, a major development in the story of metropolitan improvements in London. The Board effectively took over responsibility for planning and building new streets from the Commissioners for Woods and Forests; this was a huge step towards the centralisation of local government in London. The Board existed alongside the local vestries (based on the age-old parish system) , but took over responsibility for the entire capital’s main drains, sewage disposal, and street and bridge construction. In 1875, it was also given the power of slum clearance. This was the fulfilment of the dreams and schemes of a whole slough of writers and campaigners, for whom the fractured nature of planning derived partly from the lack of a grand over-arching authority which could override parochial concerns and beat down petty ownership, for the greater good…

‘Against the Incursions of the law’

Another neighbourhood particularly targeted by campaigners against the moral and social ills of the rookeries was the Saffron Hill area, around the modern junction of Clerkenwell Road and Farringdon Road, to the north of the City of London.

The rookery had partially evolved from a medieval Liberty – land which in medieval times belonged to a religious institution, and thus operated under church laws and courts, not the regular law. This enabled some degree of protection from prosecution by the secular authorities, and liberties became places of refuge for those with an interest in evading the law. Long after the legal distinction had in fact been removed, such areas often maintained traditions and customs of sanctuary and sometimes became rookeries.

Saffron Hill had a well-established reputation for thievery and prostitution. The area was additionally ideally situated for illegal activity and refuge, sited as it was in an administrative borderland, where responsibility for policing was split between the authority of Middlesex, the City and the parishes of Clerkenwell, St Andrew Holborn, St Sepulchre’s and the Liberty of Saffron Hill. The few constables and watchmen in service generally limited their patrols to their own patches. Such criminal legends as Jack Sheppard, Jonathan Wild and Dick Turpin were all at times said to have been residents of Saffron Hill.

As early as 1598 (when the northern end was known as Gold Lane) Saffron Hill was described as “sometime a filthy passage into the fields, now both sides built with small tenements.” (John Stow). Much of Dickens’s Oliver Twist is set here – this is the neighbourhood of Fagin and Bill Sykes.

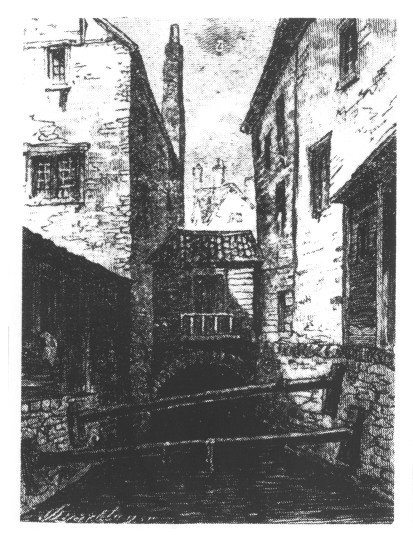

The rookery thieving community evolved a sophisticated environment to protect their trade. Much of the following evidence was only revealed through demolition during the later slum clearances to make way for the new railway and road through Clerkenwell: “Against the incursions of the law…there were remarkable defences. Over the years the whole mass of yards and tenements had become threaded by an elaborate complex of runways, traps and bolt-holes. In places cellar had been connected with cellar so that a fugitive could pass under a series of houses and emerge in another part of the rookery. In others, long-established escape routes ran up from the maze of inner courts and over the huddled roofs: high on a wall was a double row of iron spikes, ‘one row to hold by, and another for the feet to rest on,’ connecting the windows of adjacent buildings. … To chase a wanted man through the escape ways could be really dangerous, even for a party of armed police. According to a senior police officer… a pursuer would find himself ‘creeping on his hands and knees through a hole two feet square entirely in the power of dangerous characters’ who might be waiting on the other side: while at one point a ‘large cesspool, covered in such a way that a stranger would likely step into it’ was ready to swallow him up.” (Chesney)

The river Fleet, now an open drain, running through the rookery, was also utilised: “though its dark and rapid stream was concealed by the houses on each side, its current swept away at once into the Thames whatever was thrown into it. In the Thieves’ house were dark closets, trap-doors, sliding panels and other means of escape.”

The area’s most notorious low lodging house was No 3 West Street, on the north-west side of the Fleet Ditch, and at the eastern corner of Brewhouse Yard (which ran north from West St parallel to Saffron Hill, roughly where Farringdon Road now crosses Charteris Street). No 3 had once been known as the ‘Red Lion Tavern’, but for the century preceding its destruction was used as a lodging-house, a notorious haunt of thieves, a coiners gang, illegal distilling, and prostitutes. It was sometimes called Jonathan Wild’s House, or ‘the Old House in West street’, and was said to have hidden prison escaper Jack Sheppard and highwayman Jerry Abershaw. The house was adapted to serve as a hiding place, being filled with dark closets, trapdoors, sliding panels, and secret recesses, including walled off dens in the cellar, which hid refugees from the law. Even when police surrounded the place, their prey would often escape. During one raid a constable went into one of the rooms to arrest a thief, and seeing him in bed, called for other officers; he turned his head and saw the man getting under the bed. From where he vanished: there “were two trap-doors in the floor, one for the concealment of property, the other to provide means of escape to those who were hard run; a wooden door was cleverly let into the floor, of which, to all appearance, it formed part; through this, the thief, who was in danger of being captured, escaped; as immediately beneath was a cellar, about three feet square; from this there was an outlet to the Fleet Ditch, a plank was thrown across this, and the thief was soon in Black Boy Alley – out of reach of his pursuers.” In the same house, there were other, almost surreal means of escape, clearly designed by criminal genius minds, with an MC Escher-esque touch: “The staircase was very peculiar, scarcely to be described; for though the pursuer and pursued might only be a few feet distant, the one would escape to the roof of the house, while the other would be descending steps, and, in a moment or two, would find himself in the room he had first left by another door. This was managed by a pivoted panel being turned between the two.” (The Rookeries of London, Thomas Beames, 1852.)

In one of the garrets was a secret door, which led to the roof of the next house from which any offender could be in Saffron Hill in a few minutes. The house was pulled down in 1844.

Neighbouring Chick Lane was home to organised criminal gangs like the Black Boy Alley Gang which carried on a struggle against the law in the 1740s, targetting several constables & magistrates for assassination from here. Several people were hanged in the law’s counter-attack.

The poor and criminal classes of these slums not only built ingenious methods of concealment and escape: they sometimes organised their own welfare systems. The ‘Hempen Widows Club’, run from near Black Boy Alley, operated as a self-help society of the poor, one of many, which had articles including: everyone had to be prepared to swear anything to save each other from being hanged, everyone was to be prepared to swear to be a substantial housekeeper in order to bail one another from custody and members in prison were allowed seven shillings a week out of the kitty.

As with St Giles, mobs from Saffron Hill were also identified as being involved in the Gordon Riots, especially the burning of the nearby Langdale’s Distillery. (For more more on this and on Saffron Hill, check out Reds On the Green)

And, it’s very likely, poor folk from here also took part in the Crimp House Riots of 1794, the Spa Fields Riots and many other riotous gatherings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

“Physical and Moral Evil”: The Clearing of Saffron Hill

Lord Shaftesbury, a leading upper class busybody, made special studies of overcrowding and conditions in Saffron Hill to report to the House of Commons, stating: “It is impossible to imagine the physical and moral evil which resulted from these circumstances.” Imagine it they did though, and their fears led to concrete actions against the slums.

Something approaching 20,000 people are thought to have been displaced in this area between the 1830s and the 1870s by a series of calculated demolitions (though historian Gareth Steadman thought this a figure exaggerated), undertaken by the City authorities, determined to shovel the poor out from the Fleet Valley, while at the same time creating new quick transit routes to improve trade and movement of goods through the City (eg from the Docks to the West End).

In fact the poor had originally concentrated in the Fleet Valley in the first place after being gradually forced out of the City itself, by earlier ‘improvements; large numbers moved there after the 1666 Fire of London.

The ‘improvements’ in Farringdon and Clerkenwell were long in germination (plans for a road along the lower Fleet valley were first drawn up by Wren in the aftermath of the 1666 Fire, though nothing came of it then), and development occurred in stages between the 1820s and the 1880s, but the continuous road from Blackfriars Bridge to Kings Cross, although built in fits and starts, represents a consistent thread of town planning as social engineering, a continuous plan to destroy the poorest and most ‘infamous’ areas. And as John Gwynn had advocated in London and Westminster Improved, Illustrated by Plans, 1766, also allowing at the same time for ‘a noble, free and useful communication’ between Surrey and Middlesex, and of ‘amazingly improved’ property along the way.

The slum clearances included various stages: the building of Farringdon Road, (legislated for in the 1840s, though not finished until 1856), the laying of the first section of the Metropolitan Line, the construction of Holborn Viaduct in 1861 (this development alone displaced 2000 people), the enlarging of Smithfield market, the laying of Charterhouse Street (1869-75), of Clerkenwell Road (finished 1878), and finally Rosebery Avenue (1889-92).

Some of the more supposedly ‘deserving’ residents of the demolished slums were rehoused. The City managed to build dwellings for 200 individuals and 40 families when Holborn Viaduct was erected, but not even skilled artisans, never mind the very poor, were eventually placed there (“they are occupied by clerks, who keep pianos in their rooms…”). Model Dwellings built by Model Dwelling Companies and Housing Associations rehoused some 1160 people from the Clerkenwell Road area in the 1870s – though this road also passed through more ‘respectable’ artisan areas and had displaced some of those considered on the ‘worthier’ spectrum of the working classes. But as with clearances in other areas of London, the relatively high rents and strict social control imposed by the improving landlords excluded most casual labourers and their families. Effectively throughout the century thousands of poor working class and ‘lumpen’ elements, especially unskilled and casually employed, were shifted from one slum to another as inner London was gradually socially cleansed.

Clearance of undesirables was in some cases the main aim, and use of the land thus cleared only secondary. Some of the cleared land remained unused for years; Farringdon Waste, created where part of the Saffron Hill rookery stood, lay unbuilt on for several decades. The vicar of Cripplegate complained that “within the City of London there are sites amply sufficient to prevent the poor from being overcrowded – sites which for years have remained unproductive, which will long remain so, because the Corporation of the City of London has shovelled out the poor, in order mainly to lower the poor rates of the City parishes…” Ironically as several areas of empty land remained undeveloped, they themselves became partially re-colonised by elements regarded as undesirable, the focus for ‘unruly behaviour’. Congregations of boys and other idlers became a nuisance. By the 1860s the ‘Farringdon Street Wastes’, or ‘The Ruins’, as the sites were known, (now occupied by nos 29–43 Farringdon Road, adjacent to modern Greville Street) had become a well-known gathering place for ‘betting men’, and steps were taken by the City authorities to remove them.

Commercial Street: The Wicked Quarter Mile

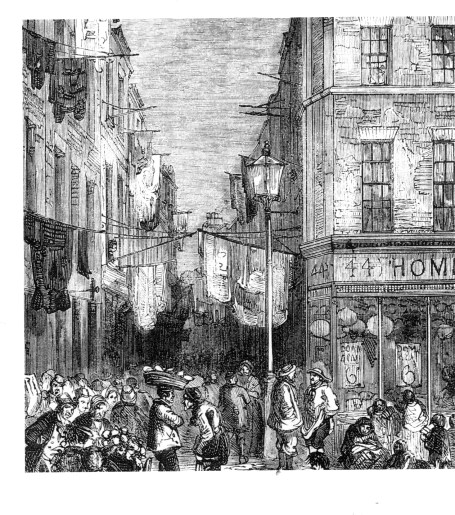

Another notorious rookery was the area around modern Commercial Street, Spitalfields, between Brick Lane and Bishopsgate. A mass of narrow alleys and dark yards; many of the buildings here were overcrowded, teeming with the poor; a good number were lodging houses, dosshouses, where the hungriest of the homeless scrounged a living, and of these most were identified by the police as haunts of criminals, thieves, prostitutes and other undesirables. A double bed would cost 8d, a single 4d and when the all the beds were taken a rope might be fixed down the middle of the room with residents sleeping against it back-to-back for 2d. Those without the money for their lodgings were evicted nightly.

Commercial Street was built in the 1840s, partly as a way of breaking up this dangerous area, filled with the poor & desperate, to “let in air, light, police, and most important of all, disturbing the inhabitants from their old haunts.” Commercial Street’s commercial value was in fact exaggerated: for twenty years as it didn’t extend far enough northwards to be of much use as a highway; but this wasn’t its main aim. 1300 poor people were evicted, and many of the most infamous areas knocked down. Each side of the new thoroughfare, tenement blocks were build by Model Dwelling Companies, (Rothschild Buildings and Lolesworth Buildings to the east, Wentworth and Brunswick Buildings and Davis Mansions to the west) sponsored by middle class housing reformers, built by pioneering Housing Associations like Peabody. Although an important motive for their construction was a desire to improve working class living conditions, and thus help stave off class violence and rebellion, and drag the immoral poor out of the gutter, in the long run the new Dwellings failed in their purpose. Rents were deliberately set high enough to make sure only most respectable of working class could afford it; certainly excluding the very poor who mainly inhabited the rookery.

Thus thirty years later Flower and Dean Street area, off Commercial Street, was still considered a ‘rookery’, and described as “the most menacing working class area of London”. The area between Wentworth Street and Spitalfields market was labelled the ‘Wicked Quarter Mile’, by outsiders.

The 1870s saw a revived campaign of middle class reformers to demolish it, a huge propaganda war waged at portraying the inhabitants as immoral, ‘unsavoury characters’ criminals, prostitutes etc. This was a time of great fear among the middle classes, after the Paris Commune rising, that the disorderly poor would, if not controlled/pacified by charity and coercion hand in hand, rise up and destroy them.

Repeated attempts of charity, police, religion, sanitary reform and coercion having constantly failed to control the Flower and Dean Street area, only demolition would do. But it took the Jack the Ripper murders to provide the push that led to the demolition of the “foulest enclaves” of Flower & Dean Street. Three of the ripper’s victims had lived lives of dire poverty in the street, and the media storm the killings roused focussed a spotlight on the area. The Four Per Cent Dwelling Company bought up the north-east side of the street and built Nathaniel Dwellings; on the north side of Wentworth Street, Stafford House was erected (thanks to the guilt-ridden landowners the Hendersons, in an attempt to banish the bad publicity the murders were spreading). Through the 1890s other blocks went up in the old rookery, between Lolesworth and Thrawl Streets.

Ironically a century later, these model blocks off Commercial Street became run down and decayed themselves, and were in turn labelled slums, and the same process would be repeated: plans were laid to scatter the residents and build new housing for a better class of inhabitant. (Only this time the tenants’ resistance would change the outcome…)

St Giles again: Cross-purposes

Thirty years after the original building of New Oxford Street, further social cleansing took place in St Giles, this time under the guise of cleansing of insanitary housing. St Giles had already seen an influx of refugees from slum clearances in nearby areas of Holborn, the City and the Strand in the 1860s, and was increasingly jammed to the rafters. Under the terms of the 1875 Artisans Dwelling (or ‘Cross’) Act thousands of residents in overcrowded London slums were evicted, and the buildings demolished. The result of sustained lobbying by housing reformers, notably the Charity Organisation Society, the idea behind the Act was that bad quality housing could be cleared, in an organised way for the first time, on the orders of the local medical officer, compensation paid to the owners, and then the land would be sold to a developer on the proviso that they would build decent working class housing.

Many of the social reformers who agitated for and sponsored such legislation knew well that it was the owners or middlemen making the money who should shoulder much of the blame for slum housing, and that many of these landlords sat on local Vestries and thus were able to defeat or delay attempts at real change. Thus the Cross Act was a disaster, making overcrowding much worse. Partly this was because excessive compensation was paid to the landlords, for land which was then not allowed under the Act to be used for commercial use, so its value dropped heavily; meanwhile, because compensation was based on rental receipts, land owners in areas likely to face action under the Cross Acts rammed more people into their properties, and lied through their teeth about the value of houses. And while the poorest were usually those evicted (in St Giles, those displaced were ‘waifs of the population, poor labourers, hawkers, thieves and prostitutes, many of who were “lying out in the streets” or found space in already crowded neighbouring buildings), where planned replacement ‘model dwellings’ were built, (which took years, and in some cases never happened), they were not the type of people allowed, or who could afford, to move in. Although the Peabody Trust built 690 tenements to replace demolished slums in Great Wyld Street and Drury Lane, there was no accommodation for barrows and donkeys belonging to costermongers, the majority of the evictees, and the rents were too high. The net effect was to increase overcrowding in the area, as most of the cleared worked locally and were unlikely or unable to move far. This kind of well-intentioned reform rewarding the property-owners and making things worse for the poor seems to have been a regular feature of late-19th Century philanthropy. Local Medical officers also openly used the Cross Act and other sanitary reform legislation to forcibly rid their manor of people they saw as scum, with little pretence of rehousing them – in St Giles in 1881, the Medical Officer reported that he saw no possibility of improvement until many of those who had been evicted were completely removed in the area, and that he “was pleased to have got rid of them.” Some 8000 people were driven out of the St Giles area in the 1870s.

Some of those cleared in Great Wyld Street (now Wild Street, off Drury Lane), were unwilling to simply play victim, and took up squatting: “they made a forcible entry into Orange Court, and were turned out of the empty houses after they were compensated by the Board of Works.”, This is a rare example of recorded resistance I have discovered to this massive program of social cleansing – though many more incidents may have been lost or not recorded, as the voices of the poor were seldom heard amidst the clamour for ‘improvement’.

The lack of recorded mass resistance to the destruction of thousands of homes and evictions is striking, especially if you compare it to the corresponding wealth of opposition to enclosure… While rookery dwellers were known for communal solidarity against incursion by bailiffs, constables and other forms of authority in the previous centuries, this seemingly didn’t evolve into collective defence of their ‘communities’ very existence… Why this didn’t occur is a vital question. Classic Marxists might well identify the slum dwellers as a lumpen proletariat who hadn’t developed a consciousness of themselves as a class; however they clearly had a sense of common interests. The ground down individual battle for survival can tend to depress and isolate, however; alienation and fatalism are often present in It’s possible that people saw the rookeries as not really worth fighting for in their actual conditions; it’s also possible that bonds of solidarity were constantly weakened by the transient nature of slum life. More research needs doing here.

Other road schemes that conveniently drove through London and Westminster slums included Victoria Street, built 1845-1851 through the Devil’s Acre rookery; Stamford Street, Southwark, built around 1860; Bethnal Green Road built 1872-1879 through the Shoreditch slums; the building of Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road 1879-1887, which bulldozed the ‘infamous’ seventeenth century rookery around Newport Market (near Leicester Square), as well as the southern part of St Giles. Mr Henry Hughes of Grosvenor Square had described Newport Market in a letter to The Times, after he had had his gold watch and chain snatched nearby, and he and a police officer had tried to give chase. ‘”Notwithstanding the vigilance of the police officers, they are baffled in their efforts, owing to the maze-like intricacy of its rows of doorless hovels, harbouring and screening those who fly there after their depredations.” Mr Hughes advocated for the area’s demolition, and soon got his way: Newport Market stood in the path of Charing Cross Road, and was knocked down in 1887.

Still later, between 1900 and 1905, Aldwych and Kingsway were built upon the Clare Market, Holywell Street and Wych Street area, also a long-established rookery with a reputation for fencing of stolen goods and criminality.

Although the evidence of the effects of slum clearance often defied the intentions of the authors of these schemes, the same approach was paramount for dealing with old and run-down districts for decades, and while brazenly admitting the motivation was often to disperse the poor, the old trope that this was for their own good and would lead to their pulling themselves up by their bootstraps was continually repeated. In 1875, Mr Leon Playfair, MP, told Parliament that ‘dispersion’ of paupers during street improvements ‘is one of the greatest advantages of such a measure …. the rooting out of the rookeries has been the cause of much moral improvement.’

The Wrong Side of the Tracks

Coinciding with the early years of the roadbuilding schemes we have already discussed, London was also experiencing the railways boom. Along with much of the country the capital was rapidly being criss-crossed by railway lines, laid by private railways companies in a mad rush of speculation…

The building of the railways were generally driven through poorer districts, as the ‘low-grade housing stock’ was the cheapest to buy up. Thousands of houses were knocked down to accommodate the lines; at least 50,000 people are believed to have lost their rented accommodation between 1836 and 1867 due to demolitions for rail building. As with the road-building schemes, many of the evicted poor had little choice but to move into already overcrowded neighbourhoods.

Railway companies had sweeping powers of Compulsory Purchase, several years before the Metropolitan Board of works was able to employ this as a way of clearing targeted buildings. This was granted by the plethora of parliamentary acts passed to authorise each rail line; completely coincidentally many MPs and Lords were shareholders in the private railway companies; some also owning large parcels of the land the tracks and stations were built on, thus receiving compensation for their loss. Where tenants would get nothing.

To what extent was railway building also used to clear areas considered full of undesirables? One notable example stands out, of a so-called notorious area that DID disappear due to the rail boom.

In 1866, the Midland Railway Company demolished Agar Town, an area several Victorian writers described as the foulest slum in London, to make way for the development of St Pancras railway station. Thousands were moved out as their homes were knocked down. Interestingly, recent studies of the area have suggested that Agar Town area was not anywhere near as much of a slum as the hype around it made out, which begs the question of why such a virulent campaign of vilification was mounted – possibly to build up a swell of support for demolition, redevelopment etc…? In any case, this area was totally eradicated in the 1860s; an entire London neighbourhood vanished under the new station and depots. (Which itself was recently re-developed into a multi-billion shiny office-cultural-residential complex, with lots of privately owned public space and up-market housing… There are timeless echoes of the clearance schemes of the 1800s – eradicating the longstanding chaotic streetlife of Kings Cross, dealers and junkies, prostitution and homelessness, has been a major bonus for the local authority… And there was some discussion of how people with mental health and other ‘complex problems’ could be excluded from housing in the social/’affordable’ newbuilds on the area – such new shiny estates should be free from such troublesome individuals…

This is far from the only example of slums demolished to make way for railways and stations. For instance, just along Euston Road to the west of Agar Town, several decades earlier, the building of the Metropolitan Line, a ‘cut and cover’ shallow underground line, ‘necessitated’ the demolition of ‘notorious’ streets to the north of Euston Road, which also allowed the road widened at this time. We’re still looking into how much the removal of the slum dwellers was part of the rationale for rail-building, and how much it was simply cheaper and easier to drive rail infrastructure through poor areas than more well-to-do neighbourhoods.

All in all, the road (and rail) schemes discussed above, the plan succeeded in destroying some of London’s rookeries, but largely failed in their more nebulous social aims – since the poor moved to slums nearby or elsewhere.

Far from opening up the labyrinths to the moral influence of the middle classes’, the new streets simply continued the segregation of the poorest, moving them here and there as areas became targeted for ‘improvement’.

Discipline and Punish

The destruction and redevelopment of poor areas, especially rebellious or uncontrollable poor areas, did not begin in the mid-nineteenth century. However, its usefulness for social control purposes gained much traction in mid-late Victorian times.

The clearing of lower Fleet Valley, St Giles and Spitalfields rookeries, among many others, was an important part of a combination of social processes that cleared most of the resident working class, and especially the rowdy, uncontrollable element, the threat of mob violence from inner London, from the doorsteps of the rich, away from the centres of business and leisure of the powerful, from the nexuses of power that ran a growing empire. Apart from removing the immediate daily danger of rebellion crime and disease from these areas, this clearing also created space for internal expansion for capital itself, on its own doorstep so to speak. How much of this was planned social engineering, how much ad hoc, and how much happy coincidence for the powers that be, is open to question. Certainly some of it was deliberate; and such processes were at work elsewhere. Much of Paris was redesigned in the 1850s-60s, under the leadership of Baron Hausmann; the wide boulevards driven through the centre, helped move troops/police around, to deal with rebellious crowds, made both administration of the city/social control more effective and speedier, and contributed to demolition of narrow, uncontrollable alleys and led to mass removal of the poor from central areas to the outskirts. (In Paris this was even more of a priority, since working class crowds had overthrown three regimes in the previous sixty years). Breaking up the potential rebellious unity of local areas, where people knew each other, shared customs, loyalties, and knew the narrow winding streets better than the authorities, was a specific aim. Like the London social reformers, Hausmann also used the pretext of bad sanitation as an excuse to destroy slums and move thousands of people to outlying areas of the city, “for their own good”, but happily also making them less threatening to authority and the seats of power.

But the destruction of the rookeries was also a crucial element of the imposition of discipline on working class. This involved many and diverse elements – the internalisation of the work ethic, splitting and separating the ‘respectable’ and unrespectable lower orders, demarcating ‘criminal subculture’ and ‘criminal economy’ as separate from respectable working lives… “regularisation of labour markets and economic activity , the moving of social and economic life off the streets by regularised employment in offices shops and factories, the organisation of social activities in youth clubs, boys organisations and the concentration of public street life into particular times and situations – public events. ‘Saturday night’ (during which police could be more lenient than at mid week), the regularisation of family life with men at work, women in the home, children at school etc…

The result was a certain stabilisation of working class communities – “the regularly employed working class assimilated to bourgeois standards of order and indeed conceptions of criminality. Those in stable employment, oriented to consumption and family, are distanced from the street economy of social crime and cheap goods of dubious origin. Consciousness of the value of property acquired from the wage, and from savings, assimilates the working class to definitions and attitudes to crime shared with the middle classes. The street thief, robbing workers of their pay packets as much as the middle classes of their wallets, or the stalking murderer, preying on the vulnerable of all social classes, becomes the paradigm of crime. During the second half of the nineteenth century the modern ‘moral panic’ about crime and violence becomes a feature of urban life, of which the two most well known examples in London are the garrotting panic of 1862 and the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.”

So earlier middle class panics about the lower orders in general was transformed into a fear, shared across the social classes, of the marginals and criminal subcultures. The respectable working class gets up on time, doesn’t drink, or not to excess, consumes and respects property and law n order, and only engages in regulated and controlled leisure pursuits. The re-organisation of streetlife and of areas where life, pleasure, work was played out in the street was a part of this re-ordering:

“The streets provided the largest and most accessible forum for the communal life of the poor. It was in the streets that members of the community came together to talk and play, to work and shop, and to observe (and sometimes resist) the incursions of intruders such as school board visitors, rent collectors and police officers… for most of the nineteenth century the poor were intensely hostile to the police, and…this hostility resulted in large measure from resentment at what was regarded as unwarranted, extraneous interference in the life of the community.” (Benson 1989: 132)

Increasingly, through the course of the nineteenth century, the police established their authority and presence in working class communities; both to deal with crime, and (more crucially) to directly impose surveillance and discipline over working class daily life; especially over streets, pubs, music halls, etc. Police were part of what historian Robert Storch called “the bureaucracy of official morality”, an active agent of the Victorian middle classes. Storch writes:

“The imposition of the police brought the arm of municipal and state authority directly to bear upon key institutions of daily life in working class neighbourhoods, touching off a running battle with local custom and popular culture which lasted at least until the end of the century… the monitoring and control of the streets, pubs, racecourses, wakes, and popular fetes was a daily function of the ‘new police’ … (and must be viewed as)… a direct complement to the attempts of urban middle class elites…. to mould a labouring class amenable to new disciplines of both work and leisure.” (Storch 1976: 481)

The police acted

“…through the pressure of a constant surveillance of all the key institutions of working-class neighbourhood and recreational life….. It was precisely the pressure of an unceasing surveillance…[in which] … the impression of being watched or hounded was not directly dependent on the presence of a constable on every street corner at all times… [but rather]… the knowledge that the police were always near at hand and likely to appear at any time.”

In the wake of demolitions of notorious streets, the emergent social housing was also used as a method of control. Model dwellings, the earliest form of social housing, was built, often in or near to the evicted slums. But only the respectable and hard-working were admitted, and codes of behaviour and morality in the new flats were strictly controlled, and rents kept relatively high, to exclude any of the ‘undeserving poor’. Part of the separation of the marginal from the conforming discussed above.

The early pioneers of Model Dwellings and other social housing reform believed that the physical environment, even the architecture, that people lived in could either sap their moral will, keep them held in poverty, or be adapted and changed to mould them into better more hardworking citizens. The layout of Model dwellings was specifically designed to have what was thought to be a beneficial moral and social effect. One of the main aspects of slum life they aimed to change was overcrowding – families having to share a room, where they slept, ate and did everything together; often even more than one family might live together in one room. Housing reformers were keen to give these poor families more space; however their pressing reason was not privacy, but because they saw this way of life as in itself immoral. Not only did it encourage immodesty and improper sexual relations (a subject of pathological obsession and innuendo for the Victorian middle class), but in a more complex and nebulous way, they thought that it formed part of a collective, communal life that should be done away with. Life publicly shared, in housing, the street, the pub, and other places of amusement, was itself somehow unconducive to respectability and self-reliance; the Model Dwellings were designed to separate people as much as possible – children from parents, one family from another. Physical space was designed to keep people apart – stairwells and other physical barriers between flats and doorways – in fact separate sanitary arrangements were built in at extra cost to reduce ‘immodest’ contact. Part of the plan was definitely a reinforcing of the patriarchal family unit, split off from a shifting wider communal society or even extended family.

Amongst the very earliest Model Dwellings were blocks built in St Giles, Clerkenwell and Spitalfields, the very areas we have seen that roads were used as slum clearance program – to specifically offer a way out, but only on certain moral terms, and only to those who worked hard enough in the right trades to afford it and signed up to live in ways that were considered acceptable.

These patterns of social control can be seen again in the late twentieth century. In the USA, from the late 1960s on, this process, when specifically and deliberately designed to rid inner cities of riotous and troublesome poor (usually African-american or latino) populations, was euphemistically labelled ‘Spatial Deconcentration’, by the government, military and corporate powers that developed it.

In 1980s Britain, after the 1981 riots, areas like Brixton, in South London, with its street culture, the refusal of the work ethic by large sections of the population, the proliferation of squatting and counter-cultural and marginal ways of life and earning of money, attracted similar attention from the improving minds… Attitudes from police and authorities identified all these elements as needing to be either repressed, or bought off with social programs, to defuse the chances of further riots as in ’81… ideally both strategies would be used in tandem. So along with schemes to ‘tackle unemployment’, fund youth centres and create programs, there were also attacks on the squatting and street cultures, evictions, targeted harassment of those hanging out on the street. But there was also some altering of urban landscapes to suit the purposes of authority: the most notorious squatted houses and ‘blues’ clubs in Dexter Road (off Railton Road) were bulldozed (Dexter Road in fact completely vanished from the map); walkways in Stockwell Park Estate that allowed rioters to bombard police from above and move rapidly around the estate during the fighting were afterwards partly removed, and the Railton Road/Mayall Road triangle, the centre of the fighting, was also redesigned, closing off ways crowds could move around, evade the police and gather again.

Areas merely associated with crime, or having a ‘bad name’, or even being working class have also been routinely altered and renamed, to shimmy the bad karma, without fundamentally dealing with the class basis and social /economic causes of poverty and ‘criminal behaviour’.

Tellingly, though, especially if you are relating urban social control and use of architecture to enclosure, observers have also long been aware that nee developments in architecture, street furniture, road and estate layout, can be subverted, used to create new methods of resistance or places of concealment, and turned back against the controllers. This can be seen as early as the sixteenth century in relation to enclosure fences, when complainants against enclosers in Neat House Fields and other areas of Westminster (officials from the parish vestry of St Martins-in-the-fields) objected to the hedges and ditches erected to enclose land, which they claim were being exploited by unruly and immoral elements (by which they seem to have meant thieves and prostitutes) to conceal themselves from observation. If there’s virtually nothing in our existence that capital can’t take and try to profit from, there’s also nothing it can create that we can’t in turn deform and reshape to our own nefarious purposes. Hilariously, the rebuilding of the ‘frontline’ in Brixton provides another example – where the demolished squats of early 1980s Vining Street were replaced by housing association newbuilds, with funky entrances that won architectural awards. Only a while later was it realised that the stairs and gates so lauded were perfectly designed for hiding dealers and other ne-er-do-wells.

Central London has gone further along the route of urban clearance than other areas of the City, or even other European capital cities (Paris excepted?). Pretty much the whole of the old City of London was cleared of its residents in the century after 1840 (although much luxury accommodation has in fact grown up in the last couple of decades). Undoubtedly this was partly because of pressures for office land, but the desire to push any possible threat from unruly plebs further away from the centres of economic power was also clear. In the case of the lower Fleet Valley, for instance, the conglomeration of crime and punishment, slum and slaughterhouse, the prisons cheek by jowl with the slums, the “dung, guts and blood” carried by the river Fleet, have been wiped from the map. (Although even in living memory, some streets of supposed ‘criminal’ character remained in the Clerkenwell area).

Processes developed here continued and were refined elsewhere. The many prisons built in the Fleet valley were erected on what was then the City’s edge, but were gradually closed down as the metropolis expanded, and public methods of punishment vanished, from being conducted in open space, replaced by those inflicted inside, and out of sight. The jails that replaced the Fleet, Newgate, the Bridewell, in the nineteenth century were themselves constructed on the then edges of town (eg Brixton, Wandsworth, Wormwood Scrubs). With motorisation our modern Newgates are often found out in the countryside far from public view – on the Isle of Sheppey, in North Yorkshire, the Cambridgeshire fens…

The rookeries’ proximity to centres of power had developed historically, organically: communities which grew up to serve as labour to the wealthy, or provide services (selling, costermongers etc), or to prey on or otherwise cream a living off (through crime or begging). As the city expanded and some people became very rich, and as transport improved and people could live further from their source of income – if they had the means – the wealthy often moved out to newer suburbs, perhaps to the west or north of London. This often left formerly good quality housing, that was ripe to be taken over and sublet, colonised by the poorer classes, where no one with more money wanted to actually live in the old inner city anymore. This process has in fact repeated and reversed several times over the centuries. Between the early 1900s and the 1970s, the populations of inner city areas declined, as people of all classes moved out to outer London or to surrounding counties. The massive program of building social housing between the world wars and after World War Two, and economic prosperity and a rise in home ownership, left vast swathes of London’s old industrial and working class areas either vacant or under-occupied, with old run-down housing and derelict land abounding. This in itself created opportunities for new occupation, both in terms of profitable redevelopment and of alternative movements like squatting. Vast changes in socio-economics and fifty years later, the inner cities are now THE place for the wealthy and middle class to live again, and all the power and wealth of state, local state, business and its entourages of media and service industry, are focused on enabling this desire. This obviously involves the removal of people considered just not productive or well off enough to justify their inhabiting very profitable inner city space – council tenants, anyone on benefits, migrants – either to be crammed into smaller spaces at a convenient distance or be forced out of the capital altogether.

And the ‘shoveling out of the poor’ continues in London; working class communities are still being broken up, in some decades more slowly and more subtly these days. In 21st century London, with what seems like a vicious urgency, local authorities, developers and property owners are effectively collaborating to rid the city of anyone whose occupation of valuable city land is seen as just not economically profitable enough. These communities don’t even need to necessarily be troublesome, rebellious or infamous these days – although there’s an element among the planners, politicians and improvers of always seeing working class people as a problem, especially where they live in social housing.

Compared to the complex tangle of motives of 150 years ago that drove the roadbuilding schemes which demolished the rookeries, today’s social cleansing has much less of a moral drive, its true; it is less acceptable to be so blatantly high-handed and dismissive of whole communities. This doesn’t mean the developers and social planners don’t hold communities in contempt – just that they have be more circumspect, dressing plans up in PR, glossy brochures, terms like social mix… It is also interesting that the social housing that was originated as a way of dealing with the people displaced from the slums in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, housing once held up as the decent, respectable and law-abiding alternative to lawless and insanitary slums, is now considered redundant, as well as unprofitable, and taking up space that a better class of people are entitled to. It is no longer thought necessary in some quarters to build or maintain social housing either to discipline the working class, or to buy them off and prevent upheaval and protest. The alternative view, to house people cheaply and well, is definitely out of fashion.

The question arises, is a movement going to arise, that can collectively challenge this process, and where is it going to come from?

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2014 London Rebel History Calendar – Check it out online

Leave a comment