The turbulent career of John Wilkes, demagogue, rakish hellraiser, sometime reformer (and eventual pillar of the establishment), through the 1760s and 1770s, seems to connect the eras of eighteenth century political libertarianism and opportunistic opposition to government corruption with the more collective movement for political reform.

Wilkes served as a figurehead for a collection of varied and almost contradictory political and social urges – the national pressure for reform of the electoral franchise, the struggle for ‘liberty’ of the subject, the teeming resentments of the artisans and apprentices against their ‘betters’… His skill in enlisting disparate elements in his personal cause was matched only by his own seeming lack of principles, and his unwillingness to push forward to the full social conclusions of his rhetoric…

Wilkes had many allies in the City of London, among powerful merchants who combined genuine opposition to the corrupt political establishment with an eye for their own advancement. He tapped into widespread desires across the country for electoral reform, among a middle class frustrated by their exclusion from political representation.

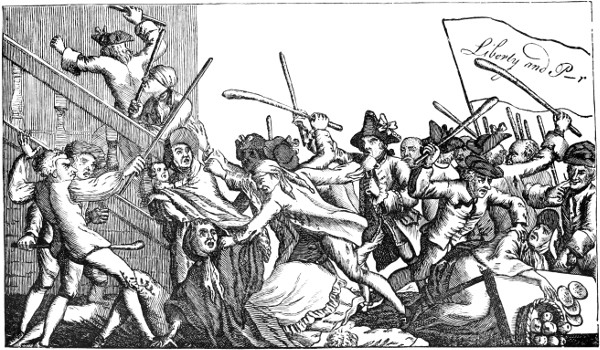

But he could also excite a rowdy mob… Several times in the years from 1763 to 1772 his supporters thronged the city of London and terrified the ruling elite.

After Wilkes, writing in The North Briton magazine (issue number 45), in 1763, criticised a speech by King George III praising the Treaty of Paris (ending the Seven Years’ War) he was charged with libel, in effect, accusing the King of lying. This got him locked up in the Tower of London for a while. However, Wilkes challenged the warrant for his arrest and the seizure of the paper, and won the case. His courtroom speeches kick-started the cry of “Wilkes and Liberty!”, which became a popular slogan for freedom of speech and resistance to the establishment. Later in 1763, Wilkes reprinted the issue, which was again seized by the government.

The ensuing uproar caused Wilkes to be flee across the English Channel to France; he was tried and found guilty in absentia of obscene libel and seditious libel, and was declared an outlaw on 19 January 1764.

Wilkes returned from exile in February 1768, a move which was to spark a huge agitation across the capital. Wilkes petitioned for a royal pardon, an appeal that went unanswered, but he was left free by the authorities. Despite still technically being an outlaw, he attempted without success to win election to the House of Commons in Westminster; when that failed, he stood for election in Middlesex in late March. Accompanied by a great crowd from London, Wilkes attended the hustings in Brentford, and was duly elected as MP for Middlesex. This result, a slap in the face for the government, caused outbreaks of wild celebrating among elements of the ‘London Mobility’, who rejoiced in the streets, harassing householders (especially the well-to-do) into lighting up their houses ‘for Wilkes and Liberty’ (smashing windows of those who refused). Despite Wilkes appealing for calm, demonstrations and riots followed for nearly two months.

The government were split as to how to deal with the situation, though ‘indignant that a criminal should I open daylight thrust himself upon the country as a candidate, his crime unexpurgated’. Wilkes then announced he would surrender himself as an outlaw to the Court of the King’s Bench, which he did on 20th April. He was initially released on bail, then committed a week later to imprisonment at the Kings Bench Prison, on the edge of St George’s Fields in Southwark, which sparked a renewal of the rioting. The Prison was surrounded daily by crowds, crying ‘Wilkes and Liberty’, ‘assembling riotously, ‘breaking, spoiling, demolishing, burning and destroying sundry wooden posts’ belonging to the prison gates and fence. On May 8th, “a numerous Mob assembled about the Kings Bench Prison exclaiming against he confinement of Mr. Wilkes, and threatened to unroof the Marshal’s house”. Wilkes made a speech from a window and persuaded the crowd to disperse, though they gathered again on the following day, demolishing the prison lobby. The 9th May also saw several riots and protests by striking workers.

May 10th however was to bring fiercer disturbances still. Being the day Parliament was due to open, the government feared that the crowds would get out of hand again, and ordered a troop of Horse and 100 Foot Guards to the Prison. Having received information that “great numbers of young persons, who appear to be apprentices and journeymen, have assembled themselves together in large bodies in different parts of this City… for several evenings last past”, the Mayor of London ordered master tradesmen to keep their journeymen and apprentices off the streets. However, from 10 in the morning, crowds gathered in St George’s Fields from all over London, estimated around 15-20,000 people were present. Various rumours were doing the rounds – that Wilkes would be released to take his seat in Parliament, that he would be removed for trial; that an attempt would be made to break into the Kings Bench and set him and the other prisoners free…

Sometime around 11 o’clock, the Southwark magistrates, sitting in their Rotation office in St Margaret’s Hill, received word from the Prison Marshal that the crowds were getting unruly. Magistrate Samuel Gillam and three other justices arrived at the Fields to find that demonstrators had broken through the ranks of the soldiers, who were lined up by the railings surround the prison. Someone had pasted up a poster bearing a poem:

“Venal judges and Ministers combine,

Wilkes and English Liberty to confine

Yet in true English hearts secure their fame is

Nor are such crowded levies in St James

While thus in prison Envy dooms their stay

Here’ o grateful Britons, your daily homage pay

Philo Libertalis no. 45.”

Justice Gillam ordered the paper torn down, which stirred the crowd up; there were reportedly shouts of ‘Give us the paper!” and ‘Wilkes and Liberty for ever!’, ‘Damn the king, damn the Government, damn the Justices!’, ‘This is the most glorious opportunity for a Revolution that ever offered!’ (which will never catch on as a demo chant). Someone even, allegedly and perceptively, shouted ‘No Wilkes, No King!’

Justice Gillam read the Riot Act, which ordered crowds to disperse or force could legitimately be used against them… in response Gillam was jeered and pelted with a volley of stones, one of which, supposedly thrown by ‘a man in red’, injured him in the face. He ordered the soldiers to pursue his assailant; Captain Murray and three grenadiers chased the man, lost him, and then shot dead William Allen, the son of a publican, in nearby Blackman Street, taking him for the men they were chasing.

Meanwhile the Riot Act was read a second time, and the foot soldiers and Horse guards were ordered to fire into the crowd, which they did, killing at least five or six people and injuring 15 more. Some of these were aid to be bystanders or passers by.

A list was later drawn up, listing eleven people killed or wounded-

William Allen (as mentioned above)

William Redburn, weaver, shot through the thigh, died in the London hospital;

William Bridgeman, shot through the breast as he was fitting a haycart… died instantly;

Mary Jeffs, who was selling oranges, died instantly;

Mr Boddington, baker of Coventry, shot through the thighbone, died in St Thomas’s hospital;

Mr Lawley, a farrier, shot in the groin, died on the 12th May;

Margaret Walters, of the Mint, pregnant, died on the 12th May;

Mary Green, shot through the right-arm bone;

Mr Nichols, shot through the flesh of his breast;

Mrs Egremont, shot through her garment under her arm…

Two men were also stabbed with bayonets.

One of the constables guarding the prison was disgusted with the soldiers, who has said had aggravated the situation by their presence, then “fired a random. A great number of them loaded three times, and seemed to enjoy their fire; I thought it a great cruelty.”

The Justices spent all day trying to get the crowds dispersed from St George’s Fields, but in the evening, “some hundreds of disorderly persons detached themselves from the Mob in the Fields” and marched to attack the houses of two of the Southwark magistrates, Edward Russell and Richard Capel, in revenge for the shootings. At Russell’s house, at the foot of London Bridge, saw the crowd break in and smash windows, stove in the front door, and steal a large twenty-gallon cask of spirits, which they drank. Russell home arrived to read the Riot Act; meanwhile Capel drove rioters off from his home in Bermondsey Street, before marching off with soldiers to join Russell and arrest some of the crowd.

There had been trouble in other parts of the capital… A crowd gathering in Palace Yard had rioted outside the House of Lords, shouting for Wilkes and that they were hungry and ‘it was as well to be hanged as starved!’ Another mob had attacked the Mansion House (the home and seat of power of the Lord Mayor)…

The day also saw demonstrations, sabotage and rioting by some of the numerous groups of workers attempting to win wage rises or protect/improve their working conditions – an explosion of workplace struggle was taking place at this time, overlapping with, sometimes feeding into or taking inspiration from, the Wilkesite movement (though sometimes rejecting it)… eg on the 10th sailors took part in a mass demo at Parliament demanding a wage rise, while in the East End, Dingley’s mechanical saw mill was torn down by sawyers whose livelihood it threatened…

The events of the 10th quickly became a cause celebre, nicknamed the ‘Massacre of St George’s Fields’, and William Allen’s death especially was widely condemned. A hastily conducted inquest concluded the two soldiers who had shot him were guilty of ‘wilful murder’, and their commander, Alexander Murray, of aiding and abetting murder. Warrants for their arrest were issued, and one for Justice Gillam soon followed, for ordering the shooting. In the end all four were acquitted, however.

Thirty four people were arrested in connection with the events of the 10th, on charges of riotous assembly, unlawful assembly invading the Justices’ houses, obstructing the Justices, and similar offences, but the government may have decided in the circumstances to tread lightly, as most were discharged without trial, and only three fined or jailed (compare this to some of the much heavier sentences for silkweavers and coalheavers arising from their strikes)… The shootings reflected badly on them, particularly as Wilkes was a few weeks later able to publish a letter from Lord Weymouth to magistrates ordering them to make more use of troops in putting down riots, enabling him to present the firing on the crowd at St George’s Fields as part of a concerted plan by a brutal and tyrannical government to repress the ‘rights of true Englishmen’.

William Allen’s death in particular aroused sympathy and outrage among Wilkes’ supporters and in the population more generally.

Distressed at the loss of his son, William’s father began a private prosecution of the three soldiers accused of his death. At this time, the majority of prosecutions were initiated and paid for by the victim and could be costly. Donald Macleane, the man who fired the musket, was tried for wilful murder at Guildford Assizes in August 1768. He was acquitted and his accomplices, Maclauray and Murray, were discharged. This only fuelled the suspicions of Wilkes’ supporters of the authorities and the government.

William Allen the elder then decided to petition the House of Commons. On the 25 April 1771 John Glynn MP, a friend and supporter of Wilkes, begged leave to bring up the petition. While the petition was the appeal of a grieving father, a greater concern was the threat of what appeared to be an increasingly oppressive government led by the king’s ministers. They had supported Macleane’s defence and through ‘oppressive and collusive acts’ had ‘entirely defeated [Mr Allen] in his pursuit of justice’. The Secretary at War, Viscount Barrington, had also commended the soldiers and rewarded Macleane. Mr Allen hoped that by petitioning parliament ‘his great and unspeakable loss should be confined to himself, and not be made a precedent, for bringing destruction and slavery upon his fellow subjects.’

The petition prompted a debate on the floor of the House of Commons. The prime minister, Lord North, opposed it being brought up, while Edmund Burke, a critic of North’s ministry, suggested the setting up of a parliamentary inquiry to look into the matter. Sir George Savile MP also spoke in favour of the petition ‘with great energy’ as it ‘came with greater propriety from a father, as he complained of the loss of a son, for which loss he was prevented by power from paying his last duty.’ A division was called by the Speaker and members voted on whether or not to accept the petition. It was decided by 158 votes to 33 that the petition should not be brought up.

The text of the petition was published shortly after being put to Parliament in the Annual Register, a publication edited by one of its supporters. It was accompanied by a letter from Mr Allen, which expressed his disappointment while thanking the MPs who supported his cause.

The death of William Allen played into the hands of critics of the King and his ministers at a time of crisis and boosted popular support for John Wilkes. He was buried in Newington Churchyard, Southwark and a large monument was erected in memory of ‘An Englishman of unspotted life and amiable disposition […] murdered […] on the pretence of supporting the Civil Power, which he never insulted, but had through life obeyed and respected.’

Wilkes himself shortly had his outlawry reversed, but was almost immediately jailed for 22 months for the various earlier charges that had got him outlawed. There followed a bewildering series of successive elections for Middlesex, as he was disqualified, re-elected, declared ineligible, a supporter elected instead… all accompanied by rioting and fights between his supporters and heavies hired by pro-government candidates.

On his release Wilkes was elected an alderman of the City of London, and gradually built up his support there, eventually convincing Parliament to allow him to take his seat as an MP. He did speak in favour of political reform and an extension of the franchise, even to ‘The meanest mechanic, the poorest peasant and day labourer’. His attempts to encourage legislation along reformist lines was however, defeated by the power of the political class allied against him.

Historians have questioned the extent to which Wilkes was ever truly committed to the programme he laid out in his March address. Some have concluded that his speeches amounted to little more than grandstanding…

Eventually he would rise to command soldiers repressing the 1780 Gordon Rioters, shooting down those who would have been his ardent supporters ten years before, and become Lord Mayor of London.

But the forces who backed him would remain in play, and as he faded into comfortable accommodation with the status quo that once excluded him, new social movements would arise to assert the demands Wilkes and his supporters had articulated, and take them even further…

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2014 London Rebel History Calendar – Check it out online

Leave a comment