“On Friday afternoon a meeting of a very alarming nature took place at Deptford amongst the Shipwrights; we are given to understand it arose about their perquisites of chips…”

Deptford Dockyard was an important naval dockyard and base at Deptford on the River Thames, in what is now the London Borough of Lewisham, operated by the Royal Navy from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. It built and maintained warships for 350 years. Over the centuries, as Britain’s Imperial expansion, based heavily on its naval seapower, demanded more and more ships, and the royal dockyards like Deptford, Woolwich, Chatham and Portsmouth were often busy, and grew larger and larger, employing more and more workers.

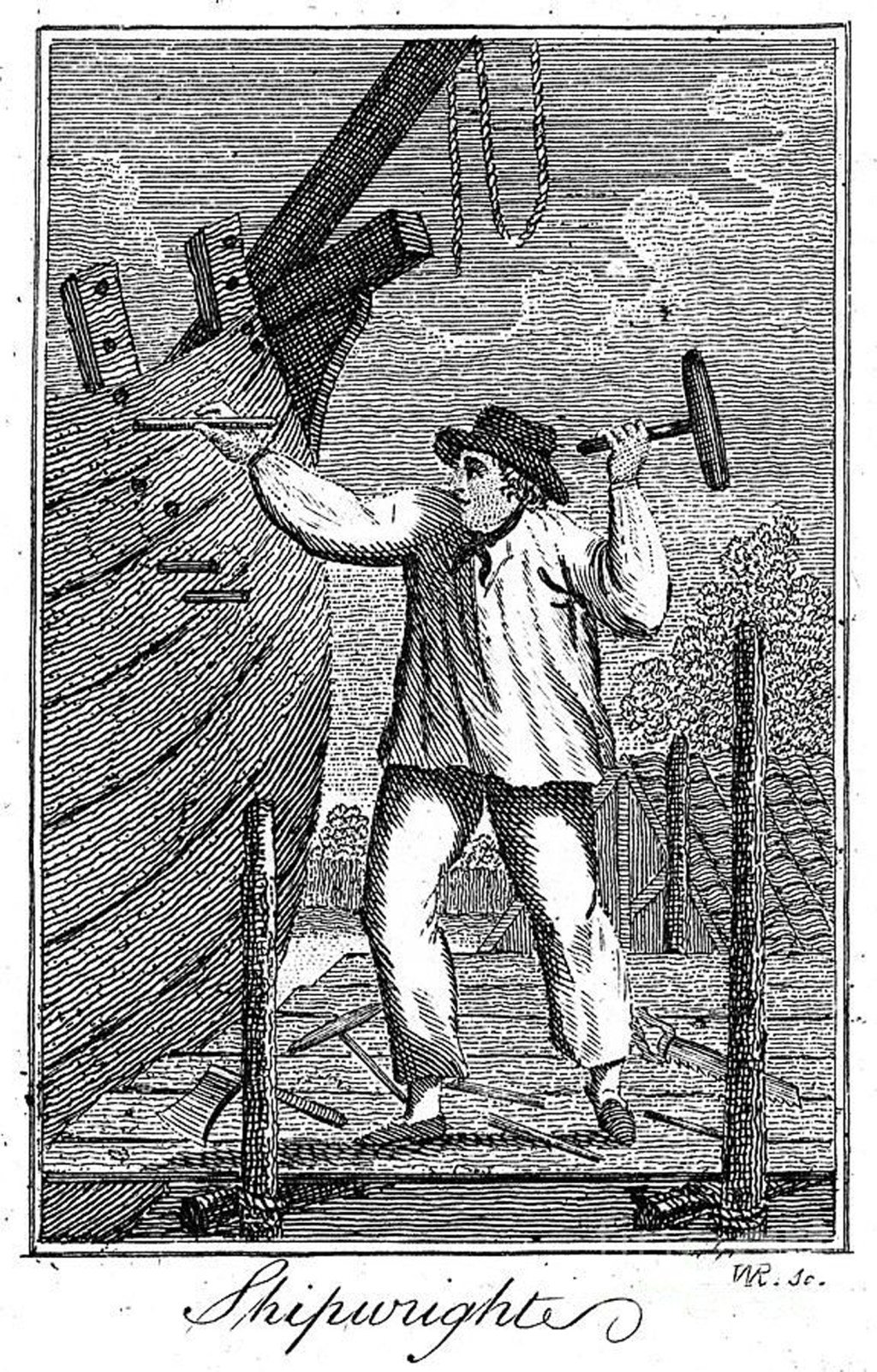

Until the 19th century, ships were largely built of wood, and shipwrights, skilled carpenters, were the backbone of Dockyard organisation. During peacetime in the 18th century it was estimated that 14 shipwrights were needed for every 1,000 tons of shipping in the Navy. There were 2581 shipwrights in the Royal Dockyards in 1804, excluding apprentices. Another 5,100 shipwrights were employed in Private English Dockyards.

“The tools of a working shipwright were those of the carpenter. In general, however, they were much heavier, as he worked in oak rather than soft wood and with large timbers. He used an adze, a long handled tool much like a gardeners hoe. The transverse axe-like blade was used for trimming timber. To fasten timbers and planks, wood treenails were used. These were made from “clear” oak and could be up to 36” long and 2” in diameter. The auger was used to bore holes into which the treenails were driven, and the shipwright had the choice of some ten sizes ranging from 2” down to ½”. A mall, basically a large hammer with a flat face and a long conical taper on the other was used for driving the treenails. Shipwrights also used two-man cross-cut saws as well as a single handsaw. Good sawing saved much labour with the adze. Other tools used were heavy axes and hatchets for hewing, and hacksaws and cold chisels to cut bolts to length. Iron nails of all sorts and sizes as well as spikes were available. Nails were used in particular to fasten the deck planks.”

Corruption and thieving were rife in the dockyards and remained so for many centuries; both in the administration, contracts etc (ie corruption of the well-to-do who ran the yards), and at a day to day level by the workers. Wages for ordinary shipwrights were low, though food and lodging allowances were often provided. For master shipwrights there were many supplements to the basic shilling a day.

Wages could fluctuate wildly, depending on many factors; and the men didn’t always get paid on time. Early in the reign of king Charles I, England was at war with Spain and France and, as the wars dragged on and the government coffers ran dry, the dockyards fell into chaos, and workers were not paid. The unpaid men stripped the ships and storehouses of anything they could cat or sell or burn for fuel. Accusations and rumour flew about, fed by envy and backbiting. The dominance of the Pett family, who were in control in all the Kentish yards, made one workman witness scared to speak out “for fear of being undone by the kindred”. In 1634 Phineas Pett was accused of inefficiency and dishonesty. The charges were dismissed at a hearing before the King and Prince of Wales but it was said that Pett was on his knees throughout the long trial. That same year the storekeeper at Deptford was charged with selling off the stores: he had not been paid for more than 14 years!

Over the centuries, the custom grew up of allowing the workmen to take home broken or useless pieces of wood, too small or irregular for shipbuilding, in theory to burn for fuel. This ‘perquisite’ of the job (or ‘perk’) was a part of their wage – in effect a way of paying the workers less in hard cash. These bits of wood were known as chips, giving an indication of the kind of size that was meant – originally pretty small, anything that could be carried over one arm. Over time, cheekiness, expectations and general resentment towards the bosses caused the offcuts being taken home to grow in size. By the 18th century the chips could be up to six feet in length, and the shipwrights had become brazen about their perks – often they would carry planks home on their shoulders, which was explicitly forbidden and considered theft. (Carrying ‘chips’ on your shoulder became a symbol of open defiance of the authorities… supposedly the origin of the term ‘chip on your shoulder’).

Canny shipwrights were having it away with ever larger pieces of wood, much of it far from broken… “Chips” were of obvious value for burning, when coal was scarce and expensive in Southern England. They were also used for building purposes: some old houses in dockyard towns can be observed to have an unusual, even suspicious, number of short boards used in their construction..!

By 1634 workmen were cutting up timber to make chips, carrying great bundles of them out three times a day, and even building huts to store their plunder. The right to chips was inevitably pushed to its limits, particularly when wages were low. Shipwrights took to sawing down full planks into ‘chips’ just below the maximum length – all when they were supposed to be working; and of nicking the seasoned wood, leaving green wood for the actual shipbuilding. The right was said to be cost the Royal Dockyards as much as £93,000 per year in 1726.

A lighter (a small transport vessel) was seized at Deptford containing 9,000 stolen wooden nails each about 18 inches long. The strong notion of customary rights was clearly expressed when the offender maintained that these were a lawful perk.

Not surprisingly, the shipyard bosses tried to restrict the taking of chips. They tried to replace the customary right with cash – paying the men an extra penny a day instead of chips. However the wrights simply took the penny and kept on carrying off the chips!

A regulation of 1753 specified that no more “chips” could be taken than could be carried under one arm. This provoked a strike at Chatham. Later, through precedent, this rule was resolved to specify “a load carried on one shoulder”.

The Navy Board was always ready to pay informers who would grass up thieving workers, but when two Deptford labourers asked for 150 guineas in return for information, they were told £25 was enough.

It wasn’t just wood that was being lifted. The list of abuses at the docks catalogued in 1729 included drawing lots for sail canvas which could be cut up and made into breeches. An informer said he had known 300 yards of canvas at a time to be taken by the master sail-maker. Bundles of “chips” could also conveniently be used to disguise the nicking of other materials; as could suspiciously baggy clothing. The Navy Board issued the following hilarious dress code regarding pilfering: “You are to suffer no person to pass out of the dock gates with great coats, large trousers , or any other dress that can conceal stores of any kind. No person is to be suffered to work in Great Coats at any time over any account. No trousers are to be used by the labourers employed in the Storehouse and if any persist in such a custom he will be discharged the yard.”

Women bringing meals into the yard for the workers in baskets, or allowed in to shipyards to collect chips for burning (much as rejected coal was gathered in mining areas) were often caught removing valuable items along with the “Chips” or more substantial bits of wood… This led to riots in Portsmouth in 1771 when the women were banned from entering the yard, having previously been allowed to collect offcuts on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

In a sudden search at all the dockyards that year, Deptford and Woolwich came out worst and the back doors of officers’ houses, which opened directly onto the dockyard, allowing for wholesale plundering of materials, were ordered to be bricked up.

Attempts to restrict or remove the right to take home chips provoked resistance, often in the form of strikes. In 1739, naval Dockyard workers at Deptford, Woolwich, and Chatham work in protest at the navy’s attempt to reduce night and tide work, the amounts of “chips” they could take as part of their wage, & over only being paid twice a year, often months in arrears. The navy backed down.

In October 1758, Deptford shipyard workers struck again, to prevent their ‘perquisites’ being removed. In 1764, marines were employed in the yard to dilute the skilled workforce; marines were also sent in in 1768, to break another strike over the threat to the shipwrights’ freebies; the wrights fought them off, however, and the Navy Board was forced to capitulate to the strikers.

A gallows & whipping post was erected to enforce the law against theft and rebellion – they were torn to pieces by the workforce.

In 1786, the conflict again provoked a strike, which seems to have begun on the 20th of October: “On Friday afternoon a meeting of a very alarming nature took place at Deptford amongst the Shipwrights; we are given to understand it arose about their perquisites of chips. About four o’clock they were got to such a pitch of desperation, that the whole town was in the utmost consternation imaginable, and it seemed as if the whole place was struck with one general panic. But happy for the security of his Majesty’s subjects, an officer dispatched a messenger for a party of the guards, which fortunately arrived at Deptford at six o’clock, which secured the peace for the moment, but were soon found insufficient, and a second express was instantly dispatched for an additional supply, these were found not capable of keeping the peace; at eleven o’clock all the troops from the Savoy that could be spared arrived, which, happy for the town of Deptford, secured the place and restored peace.” (Report from 25th October 1786)

There came a point at which the authorities decided that, whatever the unrest it might provoke, the perk had to be finally brought under control. This was achieved at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when in July 1801, in the middle of a series of large-scale shipwrights’ strikes at Deptford, the perquisite was replaced by ‘chip money’ of 6d a day for shipwrights and half that for labourers.

NB: The struggles over ‘chips’ were far from unique to Britain – 17th century naval administrators in Venice fought to prevent local shipbuilders making off with offcuts called ‘stelle’, and similarly eighteenth century French shipwrights in Toulon jealously guarded their ‘droits de copeaux’.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2018 London Rebel History Calendar

Leave a comment