Some of last week’s news outlets covered the row about road resurfacing In Oxford, where the local council had ordered one end of a street re-tarmacked, but the work stopped abruptly. Local residents from the neglected end contended that it was the middle class end where the work was done, but the working class end was left as full of potholes as ever. Some witty soul has sprayed ‘class war’ along the demarcation line…

The argument was spiced up by the fact that the very spot where the resurfacing ended once marked the infamous Cuttleslowe Wall, where a barrier was built across the road, between a council estate and a private housing development, to keep the residents of the former out of the latter. Angry inhabitants of the unreconstructed end of the street were quick to point this out – the walls might have gone, but the divide can be marked in other ways…

The Cutteslowe Walls were built in 1934. Over two metres high and topped with lethal spikes, they divided the City Council’s Cutteslowe estate from private housing to the west which was developed by Clive Saxton of the Urban Housing Company.

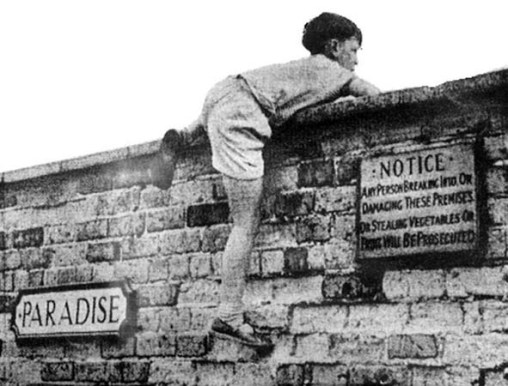

Saxton was afraid that his housing would not sell if so-called ‘slum’ dwellers were going to be neighbours, and ordered the walls built to separate them. The council tenants soon raised a petition asking for the walls to be demolished; there were several unsuccessful attempts to bring down the walls including a march in 1936 when campaigners armed themselves with pickaxes to knock them down, but police barred their way.

In June 1938 the City Council, against legal advice, took the law into their own hands and demolished the walls with a steam roller. However, the development company sued the Council, and severely criticised by the Judge, the city was forced to re-build the walls.

There were various attempts during World War II to have the walls demolished for safety reasons but these also failed. A tank on a practice exercise did (‘accidentally’ ?) drive through one of the walls, but the War Office had to pay to have the wall rebuilt.

In 1953, councils were given powers of compulsory purchase and Oxford council adopted these in 1955. Finally, on 9th March 1959, after the city had purchased the strips of land on which the walls stood (for £1000) the walls came down. Councillor Edmund Gibbs, son of an earlier campaigner for demolition, and Chairman of the City Estates Committee, took a ceremonial swipe with a pickaxe at the top of the first wall to come down.

It’s interesting that in the ‘30s the council was strongly against the wall, at least partially taking umbridge as it had developed the council end of the street. Whereas today it is accused of pampering the ‘middle class end’. The council has complained that the whole resurfacing affair is a misunderstanding, that as there are two separate roads involved the works were only ordered on the one, not the other… Convenient. It may have been that in the case of the wall it was the personal affront to the council that rankled, not the idea of social separation per se…

The 1920s and ‘30s were a time of huge migration internally in the UK, when vast new estates and suburbs were opening up, and hundreds of thousands of people were upping sticks as inner city ‘slums’ were cleared and parts of many cities redesigned. Many new estates, both municipal builds and private developments (for either owner-occupiers or private rents) were on the edges of towns and cities, where older slightly more upmarket residents were put out by arrivals of new communities, especially when some or most incomers were rehoused from poor areas. This was definitely the case at Cutteslowe, where it was the suggestion of some ‘slum clearance’ tenants that had sparked some of the fear from the private estate dwellers. But this tension was also reflected in internalised divisions among the migrating, where aspirations to a materially better standard of living was also mixed with desperation to appear respectable and achieve a more middle class lifestyle. This could also emerge as hostility to the more communal working class communities from those aspiring to live more individually, and just as virulently mirrored mocking of the snobbery of people deciding to move to the suburbs.

In fact, one study of the Cutteslowe area concluded that the difference in social class being enforced by the walls was in fact not that wide… It wasn’t a question of the wealthy being sheltered from a slum; many of the council estate tenants and the private estate dwellers were broadly skilled working class, or clerks and white collar workers… (though more of the former on the council estate). The nickname of ‘snob walls’ may well sum it up – it was a question as much of a perception of being better than someone, despite – or more because – the gap between you and them is wafer thin… Aspiration to get on, climb the social ladder, move from working class community into suburban individuality was powerful at this time, and for many, this was the first era when this became really possible. There is an element of keeping yourself separate from the people and lifestyles you want to escape… That you fear will hold you back.. Being SEEN to distance yourself from the riffraff (fear you are still part of ‘them’, despite all your aspirations?)

There’s a very interesting article on housing changes, suburbanisation, class & aspiration, in the 1920s/30s here

The Cutteslowe Wall was by no means unique, however. In London, very similar attempts were made to keep riff raff out of suburban streets.

In the borders of Southeast London and Kent, a very similar attempt at social exclusion was erected: the Downham Wall, a high concrete structure embedded with broken glass, built in 1925. Private residents in Alexandra Crescent felt it necessary to distance themselves from council tenants on the newly built London County Council Downham Estate in Valeswood Road, and to prevent the latter from walking through the posher bits to get to Bromley town centre… In February 1926, Albert Frampton, the developer of Alexandra Crescent, applied to Bromley Council to erect the wall. The council declined to take a decision, but the wall went up anyway. Allegedly London County Council and both Bromley and Lewisham Councils disputed responsibility, arguing over who should take charge – the wall was built right on the border between Lewisham and Bromley.

40000 odd working class people from Deptford and other dockside/riverside areas had been moved into new estates in middle class Downham, upsetting the established suburban respectable people. The borough of Lewisham had been traditionally been substantially middle class, proud of itself as a haven of health and respectability (although there had always been pockets of quite stark poverty), but it was the new 40,000-strong population of Bellingham and Downham, with its strong links to the riverside working class, which impinged on the respectable heart of the borough. To their middle class neighbours they seemed to bring a disreputable air, crime, unruly children, unemployment and charges on the rates. It’s also worth mentioning that some of the migrants from Deptford and neighbouring areas brought with them a fierce working class politics, trade unionism, some socialist and communist ideas… not at all what the suburbanites would presumably have welcomed. This spirit did manifest in a spreading of leftwing ideas into the new estates, for instance the communists who led housing struggles in the borderlands of south London in the 1930s. (Eg Elsy Borders and the West Wickham mortgage strike).

A line grew up dividing old middle class Lewisham from the new working class enclaves – soon solidified into the Downham Wall.

Despite considerable anger the wall was not demolished until 1950.

Read a great Municipal Dreams article on life on the Downham Estate…

Some other examples of class walls we have heard of include a barrier built to divide Springfields council estate and Acres Rise (private estate) in the village of Ticehurst, Sussex, and the ‘Fossway Barrier’ in York. In Dublin in the 1960s and 1970s as the city’s suburbs expanded dramatically (as London did in the 1920s and 30s) there were numerous cases of adjacent local authority and private housing estates being separated from each other by walls, bollards or open spaces – in places like Tallaght, Donaghmede, Coolock, Greenhills and Rathfarnham.

Other methods of social apartheid are, ot course, available…

Blocking off the roads as a means of social control is nothing new. As previously noted on this blog, the Dukes of Bedford attempted for a hundred years to keep all sorts of lowlives and tone-lowerers out of their Bloomsbury estate through the 19th century, by erecting gates and employing keepers to refuse entrance to undesirables.

But resistance to this is as old as the attempt… Tollgates put up to force people to pay for main roads used to be regularly attacked, robbed or avoided. The enclosure of large open spaces like Hyde Park, Richmond Park, Bushy Park, preventing the general hoi polloi from following old ‘rights of way’ or enjoying the space, were stoutly resisted, in the 1700s and 1800s, and mostly were overturned.

And small scale private initiatives to exclude the scum from your byways often also backfired. In Forest Hill, South London (only a couple of miles from the later Downham wall), wealthy silk warehouse owner Richard Beall tried to block off the upper end of Taylor’s Lane to increase the privacy of his posh home of Longton Hall in 1867. His attempt to do a Nicholas van Hoogstraten enraged locals, who smashed the walls & fences down; 100s came with axes & hammers! After several attempts to rebuild it resulted only in further demolitions, Beall gave up & went insane. How sad.

Of course, there are as many examples of victories for the enclosers and architects for social exclusion… More and more these days, it seems on the face of it. Gated communities proliferate – but even more so, (in London at least, though doubtless elsewhere) the gates and walls are being reversed.

The processes generally labelled Gentrification seem not to be just separating out working class communities from those with more power and wealth – but physically removing them from whole area of the city, confining them into smaller and smaller areas – or kicking them out of London altogether. Let’s face it – economically unprofitable people should just move out of valuable space which could be housing the better off.

However, as they say, a brick in the hand can be worth two in a wall…

Leave a comment