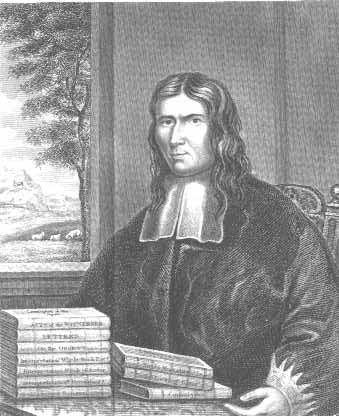

Lodowick Muggleton was a self-proclaimed prophet, who emerged from the swirling pool of sects, preachers and cults that characterised mid-17th century London. Muggleton could be said to have broadly been associated with individuals who were lumped together as ‘ranters’, though he moved away from this scene and sought to distance himself from its ‘excesses’. Nevertheless his views on religion and his elevating himself as a prophet got him into trouble with the authorities, and he was imprisoned twice for his beliefs. His follower, later called Muggletonians, developed an individual creed, and survived until 1979.

After claiming to have had spiritual revelations, beginning in 1651, Muggleton and his cousin John Reeve announced themselves as the two prophetic witnesses referred to in Revelations 11:3. Their book, A Transcendent Spiritual Treatise upon Several Heavenly Doctrines, was published in 1652. They further expounded their beliefs in A Divine Looking-Glass (1656), maintaining that the traditional distinction between the three Persons of the Triune God is purely nominal, that God has a real human body, and that he left the Old Testament Hebrew prophet Elijah, who had ascended to heaven, as his vice regent when he himself descended to die on the Cross.

According to Muggleton and Reeve, the unforgivable sin was not to believe in them as true prophets. Although they gained some notable men as followers, the group’s notions provoked much opposition. Muggleton was imprisoned for blasphemy in 1653, and his own followers temporarily rebelled against him in 1660 and 1670.

Muggleton also entered into a long feud with the Quakers, which led their leader, William Penn, to write The New Witnesses Proved Old Hereticks (1672) as an attack on him.

Muggleton spent his working life as a journeyman tailor in the City of London. He held opinions hostile to all forms of philosophical reason, and had received only a basic education. His discovery that he was a prophet emerged from his musings about resurrection and hellfire. Having somewhat despairingly concluded that he must leave it all to God, “even as the potter doth what he will with the dead clay”, he then began to experience revelations concerning the meaning of scripture. This was obviously influenced by other ‘prophets’ Muggleton observed speaking in London at the time.

“It came to pass in the year 1650, I heard of several prophets and prophetess that were about the streets and declared the Day of the Lord, and many other wonderful things.” Notable among these preachers mentioned by Muggleton were John Robins and Thomas Tany (Muggleton calls him John Tannye). “I have had nine or ten of them at my house at a time,” reports Muggleton. The prophets claimed power to damn any that opposed them.

Muggleton says of Robins that he regarded himself as God come to judge the quick and the dead and, as such, had resurrected and redeemed Cain and Judas Iscariot as well as resurrecting Jeremiah and many of the Old Testament prophets. Robins displayed considerable ‘magical’ talents; presenting the appearance of angels, burning shining lights, half-moons and stars in chambers, thick darkness with his head in a flame of fire and his person riding on the wings of the wind. This clearly theatrical performance left a lasting impression on Muggleton.

While Muggleton denounced Robins as a false prophet, for ‘self-deification’ and of indulging in dangerous powers many years later, he wrote appreciating Robins’ power and the belief even his enemies had in his curses.

The Muggletonian ‘movement’ was born on 3 February 1651 (old style), the date Muggleton’s cousin, fellow London tailor, John Reeve, said he had received a commission from God “to the hearing of the ear as a man speaks to a friend.” Reeve claimed to have been told four things:

- “I have given thee understanding of my mind in the Scriptures above all men in the world.”

- “Look into thy own body, there thou shalt see the Kingdom of Heaven, and the Kingdom of Hell.”

- “I have chosen thee a last messenger for a great work, unto this bloody unbelieving world. And I have given thee Lodowick Muggleton to be thy mouth.”

- “I have put the two-edged sword of my spirit into thy mouth, that whoever I pronounce blessed, through thy mouth, is blessed to eternity; and whoever I pronounce cursed through thy mouth is cursed to eternity.”

Reeve believed that he and Muggleton were the two witnesses spoken of in the third verse of the eleventh chapter of the Book of Revelation.

Throughout the period until the death of John Reeve in 1658, Muggleton seems to have acted only as Reeve’s ever-present sidekick. There is no record of him writing any works of his own nor of him acting independently of Reeve. The pair were tried for blasphemy and jailed for six months in 1653/4.

Apparently, on the death of John Reeve, there was a power-struggle between Lodowicke Muggleton and former ranter Laurence Clarkson (or Claxton) for leadership of the sect, and subsequently there were disputes with those followers of John Reeve who did not accept Muggleton’s authority.

The Muggletonians emphasised the Millennium and the Second Coming of Christ, and believed, among other things, that the soul is mortal; that Jesus is God (and not a member of a Trinity); that when Jesus died there was no God in Heaven, and Moses and Elijah looked after Heaven until Jesus’ resurrection; that Heaven is six miles above Earth; that God is between five and six feet tall; and that any external religious ceremony is not necessary. Some scholars think that Muggletonian doctrine may have influenced the work of the artist and poet William Blake.

The six principles of Muggletonianism were perhaps best summed up thus:

- There is no God but the glorified Man Christ Jesus.

- There is no Devil but the unclean Reason of men.

- Heaven is an infinite abode of light above and beyond the stars.

- The place of Hell will be this Earth when sun, moon and stars are extinguished.

- Angels are the only beings of Pure Reason.

- The Soul dies with the body and will be raised with it.

These principles derive from Lodowicke Muggleton, who added one other matter as being of equal importance, namely, that God takes no immediate notice of doings in this world. If people sin, it is against their own consciences and not because God “catches them at it”.

John Reeve’s formulation also included pacifism and the doctrine of the two seeds This credo held all humans had within themselves something from Seth and something from Cain: the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent. The former promoted faith within us, the latter promoted reasoning and desire. This is the conflict within every person. This is a predestinarian belief but, because there are two seeds and not one, humanity is not rendered abject and the innocence of Adam and Eve still has a chance of coming to the top within modern humankind.

According to Rev Dr Alexander Gordon of Belfast, “The system of belief is a singular union of opinions which seem diametrically opposed. It is rationalistic on one side, credulous on another.”

Muggletonianism was in many ways profoundly materialist. Matter pre-existed even the creation of our universe; nothing can be created from nothing. God, identified as the Holy One of Israel, is a being with a glorified body, in appearance much like a man. There can never be a spirit without a body. A purely spiritual deity, lacking any locus, would be an absurdity incapable of action in a material world (from which doctrine came Muggleton’s particular disputes with the Quakers). The man Christ Jesus was not sent from God but was the very God appearing on this earth. Speculation about a divine nature and a human nature, or about the Trinity, is not in error so much as unnecessary. At worst, John Reeve said, it encourages people to ascribe to the deity a whole ragbag of inconsistent human attributes expressed as superlatives.

Reason stems from desire and lack. Reason is not seen as a sublime mental process but as a rather shoddy trick humans use to try to get what they misguidedly imagine they want. Angels are creatures of Pure Reason because their only desire is for God so that their lack will be totally satisfied over and over again. The reprobate angel was not at fault. God deliberately chose to deprive this angel of satisfaction so that, by his fall, the other angels would become aware that their perfection came from God and not from their own natures.

Professor Lamont sees 17th century Muggletonianism as an early form of liberation theology. Because there are no spirits without bodies, there can be no ghosts, no witches, no grounds for fear and superstition and no all-seeing eye of God. Once persons are contented in their faith, they are free to speculate as they please on all other matters. God will take no notice.

Through the 1600s and 70s Muggleton entered into hostile polemics with a number of Quakers.

In 1669, Muggleton’s An answer to Isaac Pennington, Quaker was intercepted at the printers by the Searcher of the Press, and Muggleton was tipped off that a warrant for his arrest would be issued and he was able to disappear for nine months to live in hiding amongst the watermen of Wapping.

In 1675, Muggleton, as executor of the estate of Deborah Brunt, became involved in property litigation against Alderman John James. He seems largely to have been successful until his opponent hit upon the idea of trying to get him excommunicated in the Court of Arches so that he could no longer have defence of law in civil matters. At the time, Muggleton was in hiding at the house of Ann Lowe, a believer, from an arrest warrant of the Stationers Company. Hiding was now no longer a solution as Muggleton could be excommunicated in his absence if he did not appear and plead. On doing so, Muggleton was remanded to Guildhall Court on a warrant of the Lord Chief Justice. It was Muggleton’s ill-luck that the Lord Mayor that year was a stationer. Muggleton was bailed to appear to answer charges arising from his book The Neck of the Quakers broken, specifically that he did curse Dr Edward Bourne of Worcester, therein. Muggleton remarks that it was strange that a curse against a Quaker should be considered blasphemy by the established church. Muggleton’s problem was that it was common practice for recently published dissenting books to bear false dates and places of publication to escape the law. Muggleton’s bore a false place (Amsterdam, not London) but a true date, some 13 years earlier, and he should have escaped prosecution. No evidence, other than innuendo, was offered by the prosecution.

On 17 January 1676 (1677 new style) Muggleton was tried at the Old Bailey, convicted of blasphemy, and sentenced to three days in the pillory and a fine of £500. At each of his three two-hourly appearances in the pillory (at Temple Gate, outside the Royal Exchange and at the market in West Smithfield) a selection of the books seized from Muggleton were burnt by the common hangman. Considerable public disturbance arose from fights between Muggleton’s supporters and members of the public who felt deprived of their sport. Nevertheless, Muggleton (who was no longer a young man) was badly injured. Muggleton’s attempts to get himself released from Newgate gaol were frustrated because his keepers were reluctant to let go a prisoner from whom they could derive a profit. Muggleton was advised to get Ann Lowe to sue him for debt so that a writ of habeas corpus would remove him from Newgate to the Fleet prison. Eventually, the Sheriff of London, Sir John Peak was persuaded to release Muggleton for a payment of £100 cash down.

Lodowicke Muggleton died on 14 March 1698 aged 88.

In 1832, some sixty Muggletonians asubscribed to bring out a complete edition of The Miscellaneous Works of Reeve and Muggleton in 3 vols.

Muggletonianism has been called “disorganised religion”. Believers held no annual conferences, never organised a single public meeting, seem to have escaped every official register or census of religion, never incorporated, never instituted a friendly society, never appointed a leader, spokesperson, editorial board, chairperson for meetings or a single committee. Their sole foray into bureaucracy was to appoint trustees for their investment, the income from which paid the rent on the London Reading Room between 1869 and 1918.

Muggletonian meetings were simple comings-together of individuals who appeared to feel that discussion with like-minded believers helped clarify their own thoughts. “Nothing in the Muggletonian history becomes it more than its fidelity to open debate (though sometimes rancorous).”

Records and correspondence show that meetings took place from the 1650s to 1940 in London and for almost as long in Derbyshire. Regular meetings occurred at other places at other times. Bristol, Cork, Faversham and Nottingham are among those known, and there were many others, especially in East Anglia and Kent.

In both London and Derbyshire two types of meeting were held. There were regular discussion meetings and there were holiday meetings of a more celebratory nature held in mid-February (to commemorate the start of the Third Commission) and at the end of July (to remember Muggleton’s release from imprisonment).

There remains a description of a Muggletonian holiday meeting held at the Reading Room at 7 New Street, London on February 14, 1869. There were about 40 members present, of whom slightly more than half were men. One quarter were said to have been born into the faith. Tea was served at 5 o’clock. Discussion continued until 6 when a lady sang “Arise, My Soul, Arise”, one of the Muggletonian divine songs.Then a large bowl of port negus with slices of lemon was served and a toast enjoined to absent friends. More songs were sung by each who volunteered. Beer was brought in and supper served at half past eight. “It was a plain substantial meal; consisting of a round of beef, a ham, cheese, butter, bread and beer. Throughout the evening, every one seemed heartily to enjoy himself or herself, with no lack of friendliness, but with complete decorum.” No speeches were made. “By ten o’clock all were on their way homeward.”

There is also an account for a far older holiday meeting which Lodowicke Muggleton and his daughter, Sarah, attended in July 1682 at the Green Man pub in Holloway, then a popular rural retreat to the north of London. In addition to a goodly meal with wine and beer, a quartern of tobacco, one-fifth of a pound, was gotten through and a shilling paid out to “ye man of the bowling green”.

Outside of holiday times, meetings seem to have altered little with time and place. They comprised discussion, readings and songs. There was no public worship, no instruction, no prayer. There is no record of any participant being moved by the spirit. Until mid-Victorian times, London meetings were held in the back rooms of pubs. In the early days, this is said to have provided an appearance of outward conformity with the Conventicle Acts 1664 and 1667. The meeting would look and sound to outsiders like a private or family party. Nothing would advertise religious observance. By 1869, pub life had become irksome and the London congregation obtained their first Reading Room at 7 New Street, which was reckoned to be built on the former site of Lodowicke Muggleton’s birthplace, Walnut Tree Yard. This was made possible by legacies from Catherine Peers, Joseph Gandar and the Frost family; all of whom had been active in the faith. The money invested in government stock yielded sufficient income to pay the rent and the wages of a live-in caretaker who, for most of the Victorian period, was an unemployed shoe-repairer named Thomas Robinson. 7 New Street is perhaps the only site with Muggletonian connections still extant. However, it may require considerable historical imagination from the modern passer-by to gain a mental picture of what it would have been like in Victorian times. Then, the area was full of warehouses and factories, not the smart, professional consultancies of today.

By May 1918, wartime inflation seems to have undermined the Victorian financial settlement.The Muggletonians moved to cheaper rented premises not far away at 74 Worship Street, to the north of Finsbury Square.They remained there until probably the autumn of 1940 when the building was destroyed by a firebomb during the London Blitz. This was the event which led to the transfer of the Muggletonian archive to Mr Noakes’ farm in Kent. As a fruit farmer, Mr Noakes received a petrol ration to take his produce to Covent Garden market in central London. On the return journey, the archive was packed into the empty boxes and taken to safety.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2018 London Rebel History Calendar

Leave a comment