Mostly a London history blog, we extended our definition of ‘London’ to ‘everything inside the M25’ a while back…

… here we extend a few miles outside it. So the Metropolis is growing, yeah? Watch out, Hampshire.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

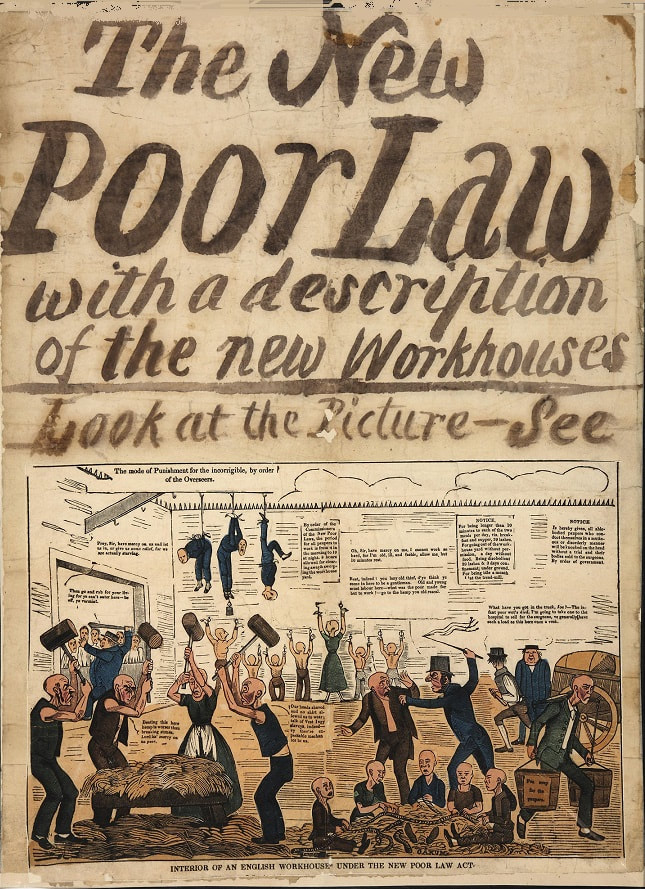

The New Poor Law was brought in in 1834, to completely replace earlier legislation based on the Poor Relief Act 1601 and attempted to fundamentally change the poverty relief system in England and Wales.

The then government had decided the ‘welfare system’ for the poor that had existed up to that point was both inefficient and overgenerous.

Until 1834, local parish authorities gave out ‘relief’ (payments of what we would call benefits) to those unable to work; this ‘relief’ was paid for from the local rates, which were mostly paid by the wealthier local residents. Who, being wealthier, often objected to paying for those less well off than themselves, seeing them as a burden and a problem, if possible to be put out of sight or into another parish. And definitely punished for being poor.

The New Poor Law emerged from a 1832 Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws; Edwin Chadwick, John Bird Sumner and Nassau William Senior had investigated current parish relief systems, sparked by the cost of poor relief in the southern agricultural districts of England where, in many areas, it had become a semi-permanent top-up of labourers’ wages.

The conclusion of the Committee basically summed up was that the provision of ‘outdoor’ relief (paying poor people who couldn’t work) was enabling people to avoid labouring when they could in fact work, and also enabling employers to reduce wage levels, knowing relief would to some extent pick up the slack. Pretty much like in work benefits today…

The Act emerged from “the classic example of the fundamental Whig-Benthamite reforming legislation of the period” – it was based three main planks of thought:

– on nasty old Thomas Malthus‘s principle that population had to be controlled as it would increase faster than resources otherwise, and that any assistance to the poor—such as given by the old poor laws—as self-defeating, temporarily removing the pressure of want from the poor while leaving them free to increase their families, thus leading to greater number of people in want and an apparently greater need for relief.

– on David Ricardo‘s “iron law of wages” which held that aid given to poor workers under the old Poor Law to supplement their wages had the effect of undermining the wages of other workers, so that old Poor Law provisions like the Roundsman System and Speenhamland system led employers to reduce wages; Ricardo called for reform to help workers who were not getting such aid and rate-payers whose poor-rates were going to subsidise low-wage employers.

– on the Whig guru Jeremy Bentham‘s utilitarian theory that people would do what was pleasant not what was horrible, and would tend to claim relief rather than working. No shit Jezza, not that claiming relief wasn’t anything but demeaning but work was worse. Bentham was the father of a lot of theories and inspired many 19th century laws, his mix of coercion and vague top-down moral improving ‘concern’ without any kind of understanding was the perfect fit for the whole age.

Edwin Chadwick, a major contributor to the Commission’s report, took up and ran with Jeremy Bentham‘s theory of utilitarianism: the idea that the success of something could be measured by whether it secured the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. This idea of utilitarianism underpinned the Poor Law Amendment Act. Bentham believed that “the greatest good for the greatest number” could only be achieved when wages found their true levels in a free-market system. Chadwick believed that the poor rate would reach its “correct” level when the workhouse was seen as a deterrent and fewer people claimed relief. Fucking funny idea of ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ there Ed.

Fellow Commissioner, Economist Nassau William Senior and Bishop John Bird Sumner were big admirers of Malthus. Bird in fact was as mad as a badger for Malthus’ theories, seeing the Malthusian principle of population as central to God’s Divine Plan, describing it as producing benefits such as the division of property, industry, trade and European civilisation…

The new Poor Law Act was intended to curb the cost of poor relief and address ‘abuses’ of the old system (ie “dole scroungers”), prevalent in southern agricultural counties, by creating a new system to be brought in under which relief would only be given to those agreeing to be ‘housed’ (imprisoned) in workhouses. To ensure skivers and shirkers would not be a burden in the rates, conditions in workhouses would be made so horrible and oppressive only the truly destitute would apply for relief.

The basis of the 1834 Law was a uniform approach, segregation and classification, reduction to the worst and meanest.

“Into such a house none will enter voluntarily; work, confinement, and discipline, will deter the indolent and vicious; and nothing but extreme necessity will induce any to accept the comfort which must be obtained by the surrender of their free agency, and the sacrifice of their accustomed habits and gratifications.”

Different classes of paupers should be segregated; to this end, parishes should pool together in Poor Law Unions, with each of their poorhouses dedicated to a single class of paupers and serving the whole of the union.

The separation of man, wife and often children was necessary, in order to ensure the proper regulation of workhouses”; only for imposing more misery really.

The new system would be undermined if different unions treated their paupers differently; there should therefore be a central board with powers to specify standards and to enforce those standards. of the legislative workload that would ensue.

Mothers of illegitimate children were directed to receive much less support than they had before, and more punishment; poor-law authorities should no longer attempt to identify the fathers of illegitimate children and recover the costs of child support from them, as had been the practice. Letting the men off the hook and blaming everything on women, hmm.

The basis for this was all pro-man. ‘Penalising fathers of illegitimate children’ reinforced pressures for the parents of children conceived out of wedlock to marry, and ‘generous payments for illegitimate children’ to the mother failed to punish her enough for not getting married. Pretty disgusting but par for the course for the time.

Most of Parliament voted enthusiastically for the Poor law, only a few Radicals (such as William Cobbett) voted against. The act was implemented, but the full rigours of the intended system were never applied in Northern industrial areas; however, the apprehension that they would be contributed to the social unrest of the period.

‘Poor Law Unions’ of several parishes were to be formed, and new workhouses built, centralising the system, and – crucially for the authorities – keeping costs down with economies of scale, bulk provision of low quality food, and employment of bullying officials. The very poor and destitute wanting help would be forced to enter the Workhouse, where they would be fed, and housed, but under vicious prison-like conditions, forced to work for every morsel of (often think and disgusting) food.

Unsurprisingly, these proposals went down like a lead balloon with the poor.

In the north of England the new Poor Law was met with protest, riot and uproar. Even more serene rural Buckinghamshire was not immune from revolt…

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded parish workhouses in operation in South Buckinghamshire, at in Amersham, (for up to 75 inmates), Beaconsfield (40), Chalfont St Peter (80), and Chesham (90).

Chesham’s old workhouse was located on Germain Street (the building was later used by Chesham Grammar School).

Amersham Poor Law Union was formed on 25th March 1835 to centralise the various parishes above. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 14 in number, representing its 10 constituent parishes of Amersham (2), Beaconsfield (2), Chalfont St Giles, Chalfont St Peter’s, Chenies, Chesham (3), Chesham Bois, Penn, Seer Green.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 15,331 with parishes ranging in size from Chesham Bois (population 157) to Chesham (5,388).

But the change in the customary administration of poor relief resulted in the same angry reaction that had seen riots in the north and midlands.

In May 1835, just two months after the union’s formation, the inmates of the Chesham parish workhouse were being moved to Amersham. (To where, exactly, is unclear as a new Union workhouse had not yet actually been built.)

However, the removal operation was obstructed by a large crowd, who objected to the inmates being taken to what everyone saw as a much worse situation.

The reading of the Riot Act caused the crowd to fall back, but the crowd followed the cart, taking out the paupers and attacking the magistrate, pelting him with earth and beating him up. The paupers were returned to Chesham.

The subsequent trial of some of those involved was the subject of a report in The Times on July 4th, 1835:

AYLESBURY, JULY 3. TRIAL OF THE CHESHAM RIOTERS.

Daniel Stone, George Benning, Henry Haycock, William Price, Daniel Brown, Mary Butterfireld, aged 37, Ann Price, aged 18, Charles Purrott, and David Morgan, were indicted for having obstructed the removal of paupers from Chesham to the Union workhouse at Amersham, and with having dragged the paupers out of the waggon. They were also charged with having beaten, assaulted, and wounded Mr. Fuller, the magistrate.

Mr. Fuller was the first witness, On the 23d of May he attended at the Chesham workhouse to superintend the removal of the paupers to Amersham and to see that no improper persons were removed. About 100 persons collected on the outside, and he was received with hissing, hooting, and yelling. Witness went out to remonstrate with them. Mr. Lowndes, another magistrate, also went among the crowd, and endeavoured to prevail on them to be peaceable, but they paid no attention to the remonstrances. The gates of the workhouse were opened to bring out the waggon, but the crowd rushed up and said “Don’t let them come out,” and closed the gates. Witness then read the Riot Act. He saw Purrott and Stone actively engaged in the crowd. They rushed up with the people and

assisted in losing the gates. After the Riot Act was read, the crowd gave way and allowed the waggon to come out.

Witness followed the waggon, and a great crowd also followed, mostly women and lads. At the end of Amy-lane, through which the waggon passed, some stones were thrown, and violent language was used. The women excited the men, calling them cowards, and said “the men of Chesham had no spirit, or they would not suffer the poor people to be taken away.” At Amy-mill the wagon was stopped: the driver struck the people with his whip, and insisted that the waggon should go on. The waggon then again went on, and the people followed.

As it was going up the hill stones were thrown, some of which struck witness. Someone put the drag under the wheel and prevented the waggon going up. At the Mill the crowd called out to the paupers, when the waggon was stopped, “Get out. Why don’t you get out?” The paupers refused to get out and one who was sitting at the tail of the waggon drew out a knife and threatened to cut off the hand of anyone who approached. On the hill they took the tail board of the waggon out. He saw Purrott, Stone, and the boy Price then present. Benning, and Butterfireld, and Ann Price he afterwards observed near the same spot. Stones were flying in showers, and the witness was struck by several of them. The crowd threw stones under the wagon to disable the horses, and some over the waggon.

Witness left the waggon for a short time, and the crowd then followed it more actively than before, and pulled one of the paupers out at the side of the waggon. Witness again followed. On Chesham-common witness found the man lying on the ground who had pulled at the side of the waggon. Witness again followed. On Chesham-common witness found the man lying on the ground who had pulled out his knife with his hand cut with a stone. Further on he found one of the forms, which had been taken out of the waggon, and broken. He observed that the waggon was empty and the crowd were bringing the paupers back in carts. Witness retreated to one side of the road to avoid the crowd but they observed him, and threw stones at him. There was a cessation of the throwing of stones for a

few minutes, and Daniel Brown then came forward to ask witness a few questions. Several others came up and surrounded him, among whom were Purrott and Benning. They asked witness for beer, saying they would let him go if they gave him some, and they greatly abused him. he refused to give them any beer, saying he had no money, but they answered that his credit was good at the public-house, and they could get plenty if he gave an order. The women stood in front round him, and the men on the outside, and the men pushed the women against him, and drove him about. Ann Price was among the women. Clods of turf and stones were also thrown at him. He slided away from them, and was proceeding towards his farm, when he received a blow at the back of the head,

which cut through the hat and penetrated through the flesh to the bone. In the afternoon witness then went to the workhouse at Chesham, his head was then tied up, and he was covered with blood. There were about 400 or 500 persons present, and they abused him, observing, “What a pretty figure he cuts now.” Witness was so much alarmed at the conduct of the crowd that he would not go home alone.

Mr. Maltby then proceeded to address the jury on behalf of the defendants. He observed that he was instructed by the defendants to express their deep regret at the acts of violence that had been committed upon Mr. Fuller. Not one of the defendants, however, was proved to have committed that violence, but on the contrary, one of them had assisted him when he was struck with a stone at the back of the head. He hoped the jury would look with to the circumstances under which the disturbances occurred. An act had passed which changed entirely the face of things as regarded the Poor Laws, and altered the condition of the poorer classes. It was impossible to

calculate the deep degree of interest that the act excited among the poor people. Even in Parliament it was most warmly opposed.

When the provisions of that measure were to be carried into effect for the first time in the parish of Chesham, and when the people saw the carriage drawn out which was to separate relations from relations, and friends from friends, and to convey them to a distant town, he put it to the jury whether it was not likely to cause a very great excitement.”

All the defendants except Henry Haycock were found guilty of riotous assemblage and given prison sentences of between 14 days and 4 months.

This was not the only protest at the New Poor Law being imposed locally: Ratepayers in neaby Chalfont St Giles had petitioned against the closure of the workhouse there, and a crowd, mostly women, threw stones when paupers were moved from that at another South Bucks town being integrated into the New Amersham Union, Beaconsfield.

Two troops of soldiers were required in May 1835 to finally ensure the successful transfer of paupers from Chesham at the next attempt.

The new Amersham Union workhouse was eventually built on Whielden Street at the south of Amersham in 1838.

Workhouses became, s the architects of the New Poor Law and Parliament had intended, feared, hated and legendarily avoided prisons for the poorest of the working classes. Far from helping to raise wages, because poverty and destitution was not a lifestyle choice but a bulwark of the developing capitalist industrial system. Wages were raised – throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries – by class struggle and organised workers getting together to strike.

Struggles against the appalling conditions in the workhouses continued from the inside, as in the Belmont workhouse inmates riot, in Sutton, in 1910. A workhouse which later became a labour camp for the unemployed and faced further organised resistance…

And the organised unemployed also targeted occupation of hated workhouses, like Wandsworth Workhouse in 1921.

There’s much more on local workhouses at Workhouses.org

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

This Way to 1834

In 2013, the Anarchist Time Travellers created an exhibition for the London Anarchist Bookfair Radical History Area.

It compares the language of politicians debating the introduction of the New Poor Law, in 1834, which made imprisonment in the Workhouse the main ‘welfare’ the poor could expect, and the current language used by today’s politicians as they ‘reform’ benefits.

Spot the difference:

Leave a comment