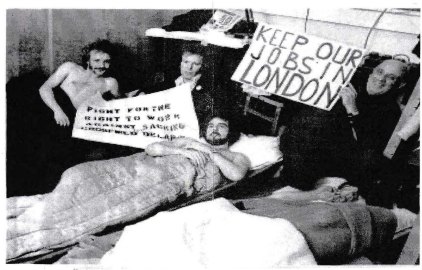

At clocking out time on March 6, 1975, 300 workers at Crosfields Electronics factory in Archway were told they were to be laid off as from that moment. Some, thinking there was no alternative, accepted the redundancy money. Others, however, decided not to take this kind of treatment and occupied part of the factory on March 26. They began a sit-in which they kept up, 24 hours a day, for the next two months.

Crosfield Electronics was a British electronics imaging company founded to produce process imaging devices for the print industry. The firm was notable for its innovation in colour drum scanning in its Scanatron (1959) and later Magnascan (1969) products.

Crosfields produced photo-scanning equipment for the print and newspaper industry, developing the first digital scanner for the printing industry in the mid 1970s. They had a factory at 766 Holloway Road, on the corner of Elthorne Road (possibly now where Whittington House is today?).

The company was bought in September 1974 by the De La Rue Group – a big multi-national company. The workers were assured there would be no redundancies, But De La Rue had decided to run down and close Holloway Road and transfer production to its Westward factory in Peterborough. The 300 redundancies might only be the first step in a gradual shutdown of De La Rue’s London Workings.

In March 1975, 300 employees at Crosfields Holloway plant were informed that they were to be made redundant in accordance with management’s decision to transfer production to the company’s factory at Peterborough.

On March 26th, some of the workers began a a sit-in with the intention of saving their jobs. The fitting-shop building which was to be imminently closed, was occupied. Workers from other parts of the factory assisted in barricading the building. Around 30-40 workers were involved, a mix of male and female employees. They occupied the whole workplace, some bringing their children into the factory during the occupation.

Many of the workers involved had previously experienced similar redundancy – some three, four or even five times.

1970s Britain saw a large wave of factory occupations by workers, as restructuring and decline caused massive upheaval, threats of closure and management attacks on wages and conditions.

The sit-in lasted 49 days.

These were far from the first jobs in North London lost in this way. 30,000 Jobs, for instance, were lost in Islington alone between 1966 and 1971. The government was offering subsidies to firms which moved development areas outside the capital, and there had been an enormous flight of industrial capital from London. At the same time there were few major developments in manufacturing in London, and no plans for any.

For many who lost skilled industrial jobs, they were unlikely to find new ones, and ended up seeking lower paid work in the service industries.

The attempt to close down production at the Holloway plant should be seen in context of two growing trends at the time: a shrinking of the UK manufacturing sector, partly as a result of restructuring and ‘rationalisation (notably after takeovers of smaller firms by larger, often transnational companies) – and a particular move to close down factories in London and move production elsewhere, often to cut wages and costs.

There was a notable rising rate of redundancy in London, and new manufacturing industry was not opening up to replace pants that were closing. What happened to Crosfields’ workers illustrated vividly the fate of employees at many smaller firms which were subjected to ’rationalisation’ when incorporated into bigger companies by take-overs and mergers. Many workers were faced with the choice of redundancy or moving out of London to keep their jobs.

The question was asked at the time, Why was this plant being shut down? Was it because of economic difficulties? Was it because of lack of orders? Was it because of ’cash flow’ problems? Had Crosfields been a bad acquisition for De La Rue? Or was it because Crosfields had, over a period of time, become a highly organised factory, with high trade union membership…?

Lynne Segal and Alison Fell interviewed some of the twelve women involved in occupying Crosfields about their fight:

“How many women worked here?

— About 90, in the whole factory.

How many are here now?

—There’s only about 12 of us fighting it. Occupying. What were your exact jobs?

— We were classed as wirewomen – wiring is when you use a soldering iron and make up chassis.

Have many of the other women been able to get jobs?

— No, there’s very few of them working. I meet them outside walking around.

The ones who have got work, where have they got it?

— They’ve not got it in wiring, there’s nothing like that left in London, you have to go away outside.

Are you all from Islington?

—Well, I’m from Islington, most are Islington or area.

—One woman who left’s working in a cafe round the corner. She was a deputy supervisor —wages must have been £75 a week. She’s lucky if she’s getting £30 now. I wouldn’t let the governors see me come down in the world like that.

—Some are working in the hospitals and taking home less than £20. Some are charwomen.

Have any of the women moved to Peterborough?

—No, there were only about ten out of 300 offered jobs in Peter borough. That was a lot of rubbish, them saying it.

—Really they just weren’t interested, they just wanted to get rid of all this building.

You’d had a few fights here to get your wages up before the occupation, hadn’t you?

— We had good money here because we had a good union and they fought and got us good rates. I think we were the best paid factory for this area round here. And listen, we’d have been up to equal pay in April, because that’s when it was to start from. But you see they have got us out, they gave us redundancy in March.

When you first had notice of redundancy, what did you feel?

—Oh, it was terrible, terrible. That’s the reason why a lot of the women went, you know, they were getting harrassed, they were getting a bit pressurised to get out.

—I think there was a lot of confusion because you must remember this came right out of the blue, nobody was expecting it.

—At the end of the day, they got you into a meeting and then they sent the line managers to tell the workers they were going to be redundant because the factory was closing down. It was shocking. People cried.

Did you spend a long time casting round to think what to do?

—There was no time

—it was late on when we were told, everyone was clearing the shop. There was a bit of bribery if you went straight away.

—I believe a lot of the managers were getting bonuses to get the shop cleared quickly.

Did any of you have families who reckoned you shouldn’t fight it, that it was a losing battle?

— No – my husband asked me two questions; ‘Had you a good job there?’ I said I had a smashing job. He said, ‘Were you happy?’ I said I was happy in that job. He said, ‘Then it’s worth fighting for.

So get back there.’

What about problems with kids and childminding now?

—My children are at school.

—Mine are grown up.

—Those with younger children used to pay to have them minded, it used to come from the woman’s wage. Now they can’t afford it. They find it hard to get down here and hard to manage.

When some of you decided to stay and fight, did you feel isolated?

—No. It doesn’t worry us. They call us things. ‘Militants.’

—They were traitors to walk away, those who left. Because we all voted not to Accept redundancies.

Do you get criticised by neighbours and friends?

—Yes, I was called a militant.

—No, my personal friends say ‘I agree with you.’

What about the women who left?

— I don’t see them. Even if I see them, love, I don’t speak to them, I hold my head up high.

Some women must be really pleased you’re fighting, thinking about their own jobs?

—Aye, I think it’s good. I feel happy fighting it. I think I would have

been miserable if I’d walked away with my tail between my legs.

How long do you think you can hold out for?

—Don’t know. If it takes a year, a year and a half.

—You see, if you don’t fight to stop them taking the jobs out of

London, they keep doing it. So you have to do something to draw the line somewhere.

What are you surviving on economically?

—The union is giving us some. £5.

—When donations come round he gives us some money.

Why can’t you get the rest made up by Social Security?

—See, you can’t —before you get redundancy money you must lodge your cards with the Labour Exchange. The governors have put the stop around – even the married men can’t get any for their wives and children.

—Crosfields slipped the word down to the SS offices. So to anyone who comes along they say you must lodge your cards, you’ve got to take your redundancy slips to show that you’ve accepted redundancy —so that would mean your fight was finished.

How do you manage on £5 a week?

—When I was working I saved. We just have to use our savings. —We have to cut down too.

Do you think you’ve got stronger and more confident as women since you’ve been occupying?

—See, I wear trousers to work now. I feel I’m one of the boys now. —Aye, we’re all pals now. We’ve got a great friendship, that we never had when we were working, with the women and the fellows. We never spoke to anyone much before, just saw them.

How do you think this affects your husbands?

—My husband says he saw more of me when I was working, because we come here evenings now.

Who makes the tea and the meals?

—The women all do a bit. The women have been doing most of the cooking though. We’re always washing dishes and cleaning up.

—We’ve tried to get the men to do it too. [During the occupation a large notice appeared on the wall, stating: ‘If you have some very good reason for not washing your cup, you may leave it here.’]

What do you see as exactly what you’re fighting for?

—Our jobs back. If I wanted redundancy money I’d have walked away at the beginning. We all want our jobs back, there’s plenty of work —I was in the middle of a job.

—I think it’s better to have your job than to be on the dole.

Will you all stay as long as the occupation lasts?

—Yes, we can’t back out now.

—We must stay till the end.

—And just think how these governors have been dirty, in a lot of ways. They’ve probably blacked us.

What will you do if you finally get defeated?

—We don’t think of defeat, we’re hoping to win.

—We’re talking about a victory party —I’m going to buy a new

dress for that. Why not, I’m no defeatist.

—One man says to me why don’t you take your money and go? But we’re hoping to win.

(Spare Rib, no 37 (July, 1975), pp. 9-10., interview by Lynne Segal and Alison Fell)

The workers raised a weekly levy to supply food to those in occupation. The dispute was well supported by fellow trade unionists. Lorry drivers refused to cross picket lines. Electricians refused to disconnect the electricity supply.

Deputations to MP’s, ministers and councillors proved that these merely passed the buck from one to the other, and did nothing to help the occupiers save their jobs. The independent Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) had a meeting with the parties in April, but no agreement was reached. Instead, the police force were used to escort finished products out of the factory in the middle of the night, and social security benefit was denied to workers’ families. The firm launched tortuous legal processes to serve writs on those in occupation.

On May 5th the employers secured a High Court originating summons claiming possession under RSC Order 113. The Summons was heard on May 9th, just four days later. A Possession Order was granted to the company, delayed only slightly by an appeal on a question of law regarding the way the summonses had been served. However, the consummate legal servant of capital, Lord Denning, ruled that there was nothing wrong with the methods used.

De La Rue used the added leverage of threatening to sub-contract out its sheet metal production, laying off more Crosfields workers.

The Crosfields workers were faced with the agonising decision of whether to attempt to remain in defiance of the court order, or to cut their losses and leave. In the end, they decided on the latter, in the face of the strength of the state forces employed against them, and because of insufficient time to rally support from wider sections of the trade union movement.

After long negotiations, shop stewards finally put it to a factory meeting that morning, that the seven reinstatements and the increased redundancy pay offer they had wrung out of the management should be accepted. The vote carried it.

Lynne Segal and Alison Fell went back to find out what the women occupiers felt:

“—They agreed to take seven, all together, back – one wireman, an electrical inspector, one labourer, two wirewomen, a plumber. What about the new redundancy offer?

An extra £175 for every year worked. It’s all right for the people who’ve been here 10 or 15 years, not the others.

How do you feel about it all?

—It’s sad, we could cry.

—We’re all sad, because there are people who fought who won’t be getting any vacancies. The convenor’s not getting reinstated. It wasn’t money we were fighting for, it was our jobs.

Do you think it’s all been worthwhile?

—Yes! We put up a good fight. We nearly bankrupted him!

—We occupied this building for eight weeks — tell me how many could do that?

Do you think you’ll be out of work for a long time?

—Yes

—I’ll try one of these government re-training things for redundant women. Huh! Fourteen pounds a week.

Will you see each other again?

Of course we will. We’ve got all the names and addresses.”

While many factory occupations in the 1970s were successful, the sheer economic power of De La Rue robbed the workers of what security they had won – they lost the fight for their jobs. As Spare Rib put it: “Despite support from other sections of the factory and from the Labour movement locally, the odds were still completely unequal; De La Rue’s cynicism in all these doings was bulwarked by the profits and power of its status as a multi-national combine, and by the laws of the land. The workers were negotiating merely with their whole lives and futures.”

De la Rue was eventually taken over by Fujifilm Japan and named Fujifilm Electronic Imaging, now FFEI Ltd. following a management buy-out in 2008.

Leave a comment