NB: Update to this post (July 2020): since this was published the application for the controversial Waterworks Festival was refused by Waltham Forest Council… One victory! The planning application for the massive expansion of the ice rink is still up in the air…

Regular readers of our blog will know that one of our obsessions is open green space in London – its history, how much of what was defended and preserved by collective action, and its present and future use…

In the capital, as in many big cities, land has often gone through many incarnations over the centuries. If some spaces have remained largely open and accessible (although that had to be fought for), some pieces of land have been split up, parts built on, some saved and other sections lost; then in some cases, returned to open space. Industry has taken over then declined or fallen derelict and been re-wilded (or re-wilded itself).

Some of this process is still going on. The long years of battling against enclosures, campaigning for parks to be built or commons and woods to be left undeveloped, are not over. Corporate interests, local authorities, admin quangos, often owning or managing space, have certain visions as to how they can be exploited; some of which clash with other viewpoints. Land is a cash cow to some; a resource to milk, or jto be sold off, built on, concreted over.

For many others of us open space remains a vital part of what makes a city liveable. Many times we have to come together to fight off attempts to enclose places we love; other times, there’s a chance to return open land lost to a useable and shareable environment. Because of the nature of land ownership, even public land ownership, campaigns to save or reclaim open space can often face an uphill battle, because the authorities who supposedly manage such resources on our behalf may see the space differently to us. (To be honest there’s often conflict about use of open space among users…)

The Lea Bridge Waterworks, where Leyton and Hackney Marshes meet, in North East London, are one space where the next developments are under up for debate at the moment shines an interesting light on past, present and possible futures. Collective resistance helped preserve part of this space in the past; community campaigns have helped fight off some recent developments, and could help re-shape the area for all our benefit…

Part of what was once open land here is threatened by the expansion of ‘leisure’ facilities… part is fenced off after failed development plans… part is open as a nature reserve but a corporate festival is planned for the next three summers (experience with other open spaces suggests this may mean increased exploitation for such large destructive moneyspinning events…)

There’s a lot of local anger and opposition, taking inspiration from the history of resistance to the loss of open land here. Parts of what was once lammas land, on the old Leyton Marsh, have been a contested zone for many decades… The high point being direct action in 1892 which helped preserve access to some of these lands…

The Icerink Cometh?

The Lea Valley Icerink, which stands off Lea Bridge Road, has applied for planning permission to expand, which would mean the building doubling in size, snaffling more of the open land around it. We ourselves love ice skating at Lea Valley, but stealing more open space to expand it is just unnecessary…

Meanwhile, on the old East London Waterworks Site opposite, there are plans for a large corporate music festival is planned for this August (and the next two summers). The site is next door to the Waterworks Nature Reserve, a lovely place, well worth a visit. Built on the former Essex filter beds, the derelict treatment plant has been allowed to fall back to nature and has been developed as a nature reserve, a cracking place for watching wild birds, but also just for wandering and hanging out. The Reserve is designated as part of a Site of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation. It’s really not the place for a festival to have plonked next door.

As campaigners Save Lea Marshes point out: “If the noise and light pollution will be significant nuisance for human neighbours, it will be catastrophic for neighbouring wildlife, particularly birds. This is simply an inappropriate place to hold a one-off one-day music festival, let alone an annual three-day event.”

As campaigners Save Lea Marshes point out: “If the noise and light pollution will be significant nuisance for human neighbours, it will be catastrophic for neighbouring wildlife, particularly birds. This is simply an inappropriate place to hold a one-off one-day music festival, let alone an annual three-day event.”

The Walthamstow Marshes Site of Special Scientific Interest is very close to the proposed ‘premises’ and birds particularly will be seriously impacted by the noise coming from the event.

The immediate chance to object to both the proposals for the festival and the expansion of the Rink closed on March 10th, but that won’t mean the end of campaigning, should the plans be approved… (The festival might fall victim to the corona pandemic, maybe…!)

There’s also been conflict for a while over the neighbouring Thames Water site…

Until the 1960s the Thames Water Site was part of the Lea Bridge Waterworks, providing water to the people of London. A complex of 25 filter beds were served by an aqueduct bringing water from the Walthamstow reservoirs further north.

The site was closed after the new Coppermill Water Treatment Works were opened. The Lee Valley Park Authority eventually agreed to take over the Middlesex Filter Beds (after first suggesting they should be filled in to make football pitches) and later took on the Essex and Leyton Filter Beds.

Today, the Middlesex and Essex Filter Beds are beautiful, important and secluded nature reserves. They show what can be achieved when industrial sites are sensitively managed to return to nature.

The whole of the site was designated as Metropolitan Open Land in the 1970s.

However, in the 1980s, the so-called Essex Number One Beds were retained by Thames Water as an operational site, first of all a ‘temporary’ pipe store; later a base for the Thames Water/Clancy Docwra mega-plan to replace the East London water mains. In the process they have completely trashed the site without any regard for its status as Metropolitan Open Land.

When Thames Water decided they wanted to offload the land, it was originally earmarked for two brand new academy ‘free’ schools, but after much local opposition this was kyboshed in the planning process, as it was a completely inappropriate site miles from any prospective catchment area, and would have increased traffic overload on the already gridlocked Lea Bridge Road.

Defence of open space on Leyton Marsh… only part of the story

(and a long and complicated story it is… bear with us!)

Campaigners fighting to preserve the open space and reclaim the Thames Water site stand in a long local tradition: this area has a long history of resistance to the enclosure if open land; as well as complex conflicts over its use. The most famous incident took place in August 1892, when 3000 people gathered to pull down railings protecting a railway that had been unpopularly run across Leyton’s ‘Lammas’ land, and wrecked the railway lines.

The land around Lea Bridge was one all Lammas lands: of old 1 August, was Lammas Day, (from old saxon “loaf-mass”)…

Lammas Day signalled the annual shift from agricultural focus from planting crops to grazing animals. It was the last day on which grass was cut for hay, and the day grazing could commence and the hunting season began. ‘The Glorious Twelfth’ – the first day for shooting grouse – is in fact Lammas Day, pushed eleven days back by the UK’s transition from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian in 1752.

The right to cut hay and graze animals on certain fields extended to all parishioners, rich or poor. Such fields were known as Lammas land. Their use belonged to everyone, ‘without regard to tenement’ – meaning you didn’t have to be relatively well-off house-owner to have Lammas Rights. If this existed by long-established tradition, it was often a tradition that had to be enforced collectively, when the rich and powerful attempted to take possession of land, fence it off, exploit it commercially, etc. Lammas Day was thus also a day when battles around enclosure often took place, as the ritual significance of the day was a central part of the rural year, and the ritual opening up of land for grazing was a useful arena for protest around loss of access. Martinmas, November 11th, the day when woods were traditionally open to all for cutting wood for fuel, was another day of ritual protest (– see Thomas Willingale’s actions in nearby Epping Forest…) The ritual importance of these dates outlasted the actual economic significance in many areas.

East London Waterworks

Waterworks were long established on the river Lea all along its length; its proximity to London and the increasing pollution of the Thames and its tributaries further west made a relatively clean water supply on the capital’s eastern doorstep invaluable. Even today reservoirs and treatment plant dominate a good part of the Lea Valley.

The waterworks lay on both banks of the Lea, bridging the boundary of Essex and Middlesex from at least 1760, whilst expansion after 1850 was concentrated on the Essex bank within the Districts of Leyton and Walthamstow.

Waterworks were established on Leyton Marsh from the early nineteenth century, as London expanded and demand for water and its treatment increased. But each successive expansion of the Lea Bridge works, from at least 1824, encroached upon ancient Lammas lands, and required the loss, buyout or extinguishment of any existing commonable Lammas rights local communities had, whether by agreement, paying compensation, or just by jumping in and ignoring protest.

Leyton, Walthamstow and Hackney parishes all bordered on each other on the marshes, and residents of all three parishes held lammas rights there. Until around 1752, Walthamstow and Leyton had ‘intercommoned’ – shared access by agreement – on what was known as the Great Mead (or Walthamstow Common Mead). This system broke down in 1752 due to a dispute over the change in the Calendar in 1751/2. After the alteration of the calendar in 1752, apparently Leyton continued to turn the cattle onto the lammas lands on 1 August (New Lammas Day), while Walthamstow went with beginning grazing on Old Lammas Day (from 1752, 13 August). You couldn’t make it up.

The land, and the return on the property rates, was a valuable public asset.

The Great Eastern Railway bought stretches of land on Leyton Marsh for the London to Cambridge line in the 1840’s, in many cases without compensation to local people, as the Railway Acts of the time did not recognise Lammas Rights. Later sections of land were bought to build Temple Mills Marshalling Yards.

A considerable portion of the Lammas lands on Walthamstow and Leyton Marsh were ‘dis-lammased’ in 1854 and handed over to the East Waterworks London Company for extensions to the treatment plants. On top of earlier land lost, this grant reduced the Walthamstow Lammas land to only 100 acres.

The loss of land to the waterworks contributed to disputes between neighbouring parishes over the remaining lammas land, already aggravated by the complex interaction of commoning, and the slightly fragmented parish borders. In 1858, Leyton challenged Walthamstow’s attempt to establish the extent of the ‘Walthamstow Slip’ (a detached part of Walthamstow actually inside Leyton’s borders) through the most valuable part of the waterworks company’s Essex Filter Beds (an attempt to prove the valuable land was Leyton’s not Walthamstow’s? With an eye to extracting profit from the Company?). By 1873 a fence was put up on the boundary between the two parishes here. By 1876, 176 acres of Leyton Lammas Land remained for the use of local people.

In 1890, the waterworks company laid railway tracks and erected fences across Leyton Marsh, blocking a traditional bridle path, in order to create an access to the new filter beds, for the transport of coal to the pumping engines. This enraged locals, already seething at the gradual erosion of access to the land.

By 1892, commoners were agitating for the marsh to be preserved as an open space, and were lobbying the parish vestry to refuse to sell their common rights to the Company.

The Leyton Vestry (Council)’s Lammas Lands Committee, a long-standing body, with responsibility for managing access and negotiate compensation for its loss, (made up of local Liberal or Tory gentlemen), ordered the water company to take up the rails and remove the fence. The Company refused, and the vestry took matters into their own hands. Four gentlemen agreed to take responsibility for a little bit of direct action, hoping to encourage the masses to join in.

On Lammas Day 1892, a crowd from Leyton, joined by a force some 2500 strong from Hackney, and led by Councillor Christopher George, a member of the Local Board and the Essex County Council, and Leytonstone resident Henry Humphries, marched on the Marsh, demolished the fence, and instigated the removal of the rails themselves. The rails seem to have run roughly north-east-southwest, from the nearby line into the waterworks.

Barbados-born Humphries, a Justice of the Peace and County Councillor in Essex, was prominent in this direct action. He was charged, along with eight others, four of whom were prosecuted under the Malicious Damages (Railways) Act of 1861.

Many working class radicals joined in the action. Like many other mainly working class areas across London and beyond, Leyton, Walthamstow and Homerton was home to a network of Working Men’s Clubs, many highly politicised, with politics that ranged through Liberal, Radical, socialist, to anarchist. These cubs were self-organised, venues for political debate, self-education and discussion – and centres for organising. Among the trade unionists and agitators that frequented the clubs, land, and access to it, had increasingly become a subject for fierce discussion and campaigning. The urban working class had remembered that their immediate ancestors had been dispossessed by enclosure. The clubs, though inherited ideas from groups like the Spenceans and the Chartists, who had identified the theft of the land by the wealthy as one of the crucial sources of poverty, and made regaining access to land a central plank of their platforms, forming organisations like the Land and Labour League. This took the form of agitation for access to urban open space for recreation and holding meetings, as well as demanding that land be nationalised of collectivised for common use…

Among the contingent from the Hackney clubs who flocked to the defence of the lammas lands were land agitators of the “Commons Defence League,” a radical association that had been founded by the well-known leftwing agitator, John de Morgan, an Irish-born radical who had for some time lived in Hackney, and had twice served time in prison for his part in riots against theft of Common Land in Plumstead, South London.

However, the East London Water Company wasn’t going to just roll over. The Company immediately took out legal proceedings against George and Humphries. And on the Tuesday after the tracks were removed, they sent out workers to re-lay them.

The following Saturday another mass meeting was called at the Antelope pub, still standing today at the top of Marsh Lane in Leyton.

The atmosphere was different this time. The Lammas Lands Committee – already embroiled in a court case with the water company – thought further direct action would endanger the case. They refused to endorse further destruction, leaving the crowd to be led by Ambrose Barker, founder of the Walthamstow Working Men’s Club. This kind of tactical split was quite common in battles against enclosure and in defence of common land, with moderate elements concentrating on legal tactics, (though sometimes tentatively endorsing direct action, when the legal case for doing so seemed solid), then pulling back, and a more fiery element often refusing to stick to legal methods…

Once again, after this meeting, thousands marched down to the Marsh and took up the rails. The water company, again, re-laid them on the Monday.

But on Tuesday, 1,500 people descended on the tracks, including a large party from Leyton and four Working Men’s Clubs in Homerton. They ripped up the rails and again knocked down the fences the water company had erected around them.

The water company had the rails re-laid yet again on the Wednesday.

However, again on the following Saturday, led by a man known only as ‘the Village Blacksmith’, the Homerton clubs gathered their full strength to yet again march on the tracks, pulling them out of the ground and scattering them all over the fields.

Five days of sabotage won the day. The water company gave up.

Local people – at a packed meeting at Leyton Town Hall on Wednesday 30th November 1892 – formed a ‘Lammas Lands Defence Committee’ to defend the George and Humphries in their legal battle with the Waterworks Company, and to oppose the Parliamentary Bill then being promoted by the East London Waterworks Company to extinguish further Lammas rights on Leyton Marshes.

Local people – at a packed meeting at Leyton Town Hall on Wednesday 30th November 1892 – formed a ‘Lammas Lands Defence Committee’ to defend the George and Humphries in their legal battle with the Waterworks Company, and to oppose the Parliamentary Bill then being promoted by the East London Waterworks Company to extinguish further Lammas rights on Leyton Marshes.

In August 1893, locals held a meeting was called to celebrate the previous year’s ‘Great Riot’. A speaker proposed that the land saved should be handed over to the local people, for purposes other than grazing. By this time the lands were mainly used for recreation, often for playing cricket.

A compromise was reached in 1893, confirmed by the East London Waterworks Act of 1894. The company withdrew all claims to enclose any part of the marsh, ended the legal proceedings against Humphries and George, and paid all their costs, as well as donating £100 to improve the bridleway. In return, the rails were allowed to stay. What looks like the remains can still be seen, in the half-exposed cobbles in the Waterworks Nature Reserve.

In 1904, local Lammas rights were commuted, to be replaced by Access Right: the land is vested with the local authorities, but is to be kept open for the whole community to use.

Under the 1904 Leyton Urban District Council Act, 111 acres of Lammas Land to the north and south of Lea Bridge Road were acquired by the Leyton Urban District Council: “vested absolutely in the Council subject to all existing Lammas Rights…and the Council shall from the passing of such resolution and subject to the provisions of this Act hold the same… as and for an open space for the perpetual use thereof for exercise and recreation and shall maintain preserve manage and regulate the same as such accordingly.”

Lammas Rights were not extinguished by the Act, which allowed for local people to receive other rights or money in exchange for their Lammas Rights. The Lammas Lands Defence Committee wanted ‘‘rights of recreation’’ in exchange for the Lammas Rights. The decision of the LLLDC to accept recreation rights in exchange is recorded in the Council minutes of 31st January 1905:

“That the Lammas Rights over the Lammas Lands acquired by the Council under and by virtue of the Leyton Urban District Council Act, 1904, be extinguished in consideration of the said Lands being devoted to the purposes of a Public Open Space or Recreation Ground, as provided for by said Act.”

In giving up their Lammas rights, local people were expecting the council would honour their side of what was, in effect, a contract: the Council and its successors are under a duty to maintain the land as “… a Public Open Space or Recreation Ground..” perpetually. This duty applied to almost the entire area of 111 acres, excepting only parcels of land of no more than 20 acres in total which could be exchanged or sold if the Council felt they were unsuitable for use as “open space or recreation ground.”

The fields at Marsh Lane did not come under this agreement and remained as Lammas land.

The 1892 victory was celebrated in an annual festival, held here for many years by the New Lammas Lands Defence Committee; formed in recent decades to commemorate the preservation of the Lammas Lands, and to help keep them free.

Common land on the marshes further south, remaining at the turn of the twentieth Century, including White Hart Field and East Marsh, was also incorporated by the local District Councils in 1904. These lands were in turn incorporated into the Lea Valley Regional Park in 1971, as part of a network of ‘metropolitan open lands’. Although no longer truly common land, public right of access remains within the metropolitan open land definition.

Although the old lammas rights of grazing animals had been replaced by more leisurely pursuits, this was not a break, but a continuity: it was the ability to access the land that mattered to people and that people felt was their right, even if the reasons had evolved. As Juliet Davis noted of Marsh Fields, “A Leyton Lammas Lands Defence Committee (LLLDC) member recalls old Leyton ‘commoners’ returning from the marsh with pockets stuffed with rabbits and blackberries. Such practices represent threads of continuity – all-be-they ambiguous – in the context of wide ranging transformations of the site over three centuries. It is arguably less the specific or historic practices of beating bounds or grazing cattle that are important for a contemporary reappraisal of common land, but the openness and possibility offered by genuinely public space for the development and layering of multiple informal and social uses and their spatial artefacts over time. Such possibility – in terms of practice and of culture – is commonly recognised as being absent in contemporary, controlled and/or privatised public spaces.”

Campaigning to prevent the enclosure and destruction of marshes in the Lea Valley didn’t end with the Leyton Lammas riots.

Between 1979 and 1985, the Save the Marshes Campaign fought to prevent the Walthamstow Marshes, further north, being destroyed for development into a marina, and a later plan to dump 8000 tons of ballast there.

Locally, the old lammas lands have seen a succession of bits of land nibbled away and attempts by the Council to flog bits off.

In 1949 Leyton Council attempted to redevelop the Marsh Lane area as a Sports Ground and to provide Leyton Football Club with a Stadium on the Lammas Land: local people opposed them and after campaigning, the Council then dropped the idea. Railway sidings were extended as far as Lea Bridge Road in the 1950s. The Gas Board also occupies some of the former lammas land.

In Lea Valley Regional Park bought all the Lammas Land to the west of the old Cambridge Railway Line from the Council under a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO). But since then, the Park authority has taken the view that it now has the absolute freehold of the land it holds and does not acknowledge the need to maintain it as Public Open Space or Recreation Ground as provided for in the 1904 Act or contract under which Lammas Rights were given up.

Over the years the Park’s denial of rights of way over our Lammas Land has been resisted. Shortly after the CPO in 1971, people refused to stop using the ancient Porters’ Way route from the Black Path to Lea Bridge Road by Essex Wharf. The Park found that they were unable to deny people’s right to use the path.

However, the Lea Valley Riding School have now taken over all the land between what was once Low Level Brook (now the Flood Relief Channel) and the former Waterworks Aqueduct, on the former Lammas Land, and the Park has from time to time denied local people right of way over the land the School occupies.

The Ice Rink now also occupies much of the land between the Waterworks aqueduct and the River Lea, on Porter’s Field – partly on land sold by the Council to a private fairground at a time when the 20 acre limit for disposal/ exchange under the 1904 Act had not yet been exceeded and partly on Lammas Land proper.

In 1993 the Council proposed fencing off over one third of Seymour Fields at Marsh Lane so that it could be used only by people prepared to pay for the use of the football pitches, and an income-generating fenced off Astroturf football pitch, with a 15 foot high fence and huge floodlights. An overwhelming negative response from local people pushed Councillors into voting against the scheme and overturning it.

And Leyton Marsh has come under further pressure more recently. Marsh Lane Fields, which continues to be referred to as Lammas Land, is outside the remit of the Lea Valley Regional Park. The western edge of this space began was built over in the late 1990s by the construction of the Leyton Freight road (Orient Way) and the Eurostar train depot. In 1989 local people had defeated plans to put Freight Road spurs across Marsh Lane Fields, but Orient Way, was eventually built, against massive local opposition and despite its rejection at the 1994 Public Inquiry.

From 2004, the loss of land here was exacerbated by development plans to relocate businesses and allotments from the Olympic site here…

The Olympics caused major upheaval in the Lea Valley, generating much hype and large profits, destruction of housing and long-standing industry. Huge areas of East London were redeveloped; in a number of areas open green space was appropriated, for training facilities, police compounds… with lots of it to be sold off for various dubious developments… Much of this nefarious dealing is documented at Games Monitor site. Large open spaces were laid out in recompense, its true, like Queen Elizabeth Park. But conflict over management of open space has if anything intensified.

One small site of resistance to the Olym-perial Project was Leyton Marsh, opposite the waterworks, where a basketball training facility was built for the duration of the games, despite many objections, and a protest camp, which attempted to block the development. Although the land was returned to open space afterwards it was heavily damaged. There was an attempt to use the land nicked for the basketball court to erect a new bigger ice-rink, to replace the existing one on Lea Bridge Road. This was defeated in court. But there’s now yet another proposal to enlarge the ice rink, doubling it in size…

The Thames Water site’s future is still up for grabs. Although the proposal for the free school was knocked back in Waltham Forest’s planning process, campaigners fear this may be overturned on appeal; especially since the government effectively own the land, the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, acting on behalf of the Education Funding Agency (now the Education and Skills Funding Agency – “ESFA”) paid the vast sum of £33.3 million + VAT to acquire the site for the pair of free school academies. ESFA were very likely aware that the site was Metropolitan Open Land but were willing to ignore the fact, and may be confident that a pliable Planning Inspector will eventually approve the change of use.

Most of the organisations, authorities and quangos who have had some involvement or responsibility for the land have behaved less than admirably. Thames Water have knowingly destroyed the site. Thames Water used to be a publicly owned utility, in theory at least, owned and operated for the public benefit. Since privatisation, had a series of owners bent on loading the company with debt and extracting as much money as they can. When the last Walthamstow Planning Strategy – the so called Core Strategy – was being adopted, Thames Water lobbied for the site to be re-designated for a “commercially viable” development: but the Inspector at the Public Enquiry confirmed that the site’s status as protected Metropolitan Open Land should continue.

The Education and Skills Funding Agency knowingly overpaid for the land, expecting compliant authorities to give them what they want.

The Lea Valley Regional Park Authority – supposed to act as custodian of the parkland as a whole – has stood by, wholly disregarding its own Park Plan and made no effort to protect the site, in dereliction of its duties to protect the Park, only paying lip service and announcing grandiose plans that have come to nothing.

The Park Authority was even offered the Thames Water site as compensation for land that it was required to give up for the Chobham Manor housing development, next to the Olympic Park. It opted to take cash compensation instead; then splurge this money on large leisure facilities and not on improving the landscape. It then stood back and did nothing while the site was purchased for a purpose that is anything but Park-compatible use.

The approval for an annual, three day, 15,000 people capacity per day, electronic dance music festival appears to fit with a continuing strategy of fencing off and eventually developing the open space here – including the lovely Waterworks Reserve.

Waltham Forest Council’s licensing department has been deluged by objections from borough residents opposed to the Premises License application of Waterworks Events Ltd. The local community has protested vehemently en masse to the Council, the festival organisers and Lee Valley Regional Park Authority, on social media and by email. However, campaigners are suspicious that the assessment of the festival’s Premises License application may be a foregone conclusion – because Waltham Forest Council’s Licensing Department, have allied with the festival’s landlords, Lee Valley Regional Park Authority, in facilitating and advising the planning process of the festival prior to the Premises License application being submitted. There’s suspicion that the Festival was given the nod of approval from at least a Senior Officer and possibly by Waltham Forest Councillors (although the Lea Bridge Road area Councillors say they didn’t know about the planned festival and that they oppose it). Is this going to be the legacy of the much-touted 2019 Borough of Culture: Waltham Forest’s precious and much loved Lea Marshes green spaces being exploited by opportunistic rich Old Harrovian (Frederick Roscoe Valadas-Letts), party animal nightclub promoters from outside the borough, to the cost of Waltham Forest’s residents?

The Lee Valley Regional Park Authority wants to ‘dispose’ of the Waterworks Centre and the land behind it, to sell it off for housing (a plan which Waltham Forest Council also supports). Is disconnecting people from the land, by fencing it off for events like this, part of their long-term strategy to turn a green field site into a brown field site, paving the way for the eventual building of housing over what should remain accessible open land?

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

We Stand at a Fork in the Way

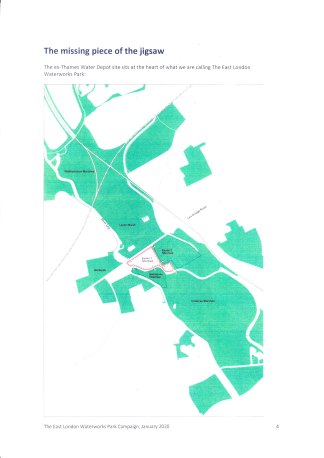

“Presently, the landscape is dislocated, with local people traversing well-worn routes into and out of each individual pocket of green space but unable to vary their walks much because of the fences they find in their way. Local people treasure these spaces, but few travel any distance to visit them and there is little to capture the wider public’s imagination. Historic buildings, such as the unusual octagonal sluice house, are hidden from view and the area’s industrial heritage and its significance as the boundary between the Danelaw and Anglo-Saxon England are ignored. Consequently, the vast potential of the area as a place to linger, a place to explore and a place to reconnect with nature is being overlooked. Re-integrating the ex-Thames Water Depot site into the landscape can change all this, bringing real health and well-being benefits to the people and wildlife that call this corner of north-east London home.” (‘The centrepiece of The East London Waterworks Park a future for the ex-Thames Water Depot site that benefits the whole community’, The East London Waterworks Campaign, January 2020)

The Thames Water site could form a connecting thread between Leyton Marshes and Hackney Marshes, linking the open spaces of the Lea valley in one continuous whole – Leyton and Walthamstow Marshes, Walthamstow Wetlands and Tottenham Marshes to the north, the Waterworks Centre and Nature Reserve to the east, Hackney Marshes and Middlesex Filter Beds to the south and the river and towpath to the west… a huge urban park where people and wildlife can roam.

Campaigners at Save Lea Marshes believe the following principles should form the basis of any decision about the land:

- The Lea Bridge Waterworks is Metropolitan Open Land and its status as such should be protected.

- The Lea Bridge Waterworks plays a critical role in connecting the marshes of the Lower Lea Valley.

- The Lea Bridge Waterworks backs on to one of the most beautiful and unspoiled sections of the River Lea, the haunt of kingfishers, stretching from the mighty Lea Bridge Weir to Friends Bridge.

- The Lea Bridge Waterworks contains significant remnants of its industrial heritage, adjacent to the weir, which can be interpreted to promote understanding of this important historical site.

- The Lea Bridge Waterworks can be linked to the Essex and Middlesex Filter Beds and managed and re-wilded over time.

The East London Waterworks Park Campaign have put forward an alternative vision to the corporate exploiters, developers, scheming councils and quangos…

Which includes proposals for a wild swimming site, an extension of the nature reserve, and opening up the fenced off land to link it up with the other green spaces it borders onto. A brilliant and far-sighted vision, well worth getting behind.

Support Save Lea Marshes in calling for the Lea Bridge Waterworks to be protected from development and opened up to public access.

Much more info here

and more on the history of the waterworks

Worth a read: (Inside the Blue Fence, An Exploration, by Juliet Davis)

Leave a comment