“I am ready and willing to dye for my Country and liberty and I blesse God I am not afraid to look death in the face in this particular cause God hath called me to.” (Robert Lockyer, 1649)

Robert Lockyer (also spelt Lockier) was born in London in about 1626. He received adult baptism in 1642, when he was 16, together with his mother, Mary, into a sect of the particular Baptists in Bishopsgate, then a suburb on London’s northeastern edge. This seems to have been where Robert grew up and had several relatives – it would also be the scene of the mutiny that would result in his execution.

Although this area had some ‘fair houses for merchant and artificers’, it had experienced a rapid building boom in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and along with Spitalfields and Shoreditch the Bishopsgate area had long also been associated with migrants, often denied entry to live or work in London, with various forms of criminal subcultures, and those looking to evade control or close scrutiny by the City authorities… Since 1500 the area’s population had increased, and refugees from the increasing enclosure of common lands, dislocation in the countryside, and the desperate seeking work, had swelled the streets around Bishopsgate. It’s unclear what Lockyer’s background was, whether his family had been resident for generations, or were relatively newly arrived… but the mix of classes, wealth and poverty side by side, the inevitable mix of ideas and resentments that arise in such ‘barrios’ may be relevant to his story.

His background in, or choice to enter, a separatist sect, the particular Baptists, is typical of many of the radicals of the English Civil War. The religious ferment, the spreading of ideas, creeds, the multiplying of branches of the protestant faith and offshoots from it, forms a vital backdrop to the English Revolution. It wasn’t just that freedom to worship as they chose, in small and self-directed congregations, without interference from the Anglican Church authorities with their secular backing from the king, was a huge demand that bubbled up for decades before the 1640s. Many of the sects were also developing radical critiques, both is purely religious terms, and when applied to the social order around them. This was harshly repressed for a century after the Reformation, but with the struggle between parliament and king out in the open, would erupt in a multi-shock volcano of ideas, proposals, and programs, and manifest in word, print and action. They saw themselves as the Saints, God’s own, though their views often diverged at to what God approved of and what kind of world He would want them to build, and as to what role the Saints themselves had in doing God’s will on Earth…

The Baptists in particular produced many political radicals in the English civil war period, as they had in the 16th century, when, known as ‘anabaptists, usually by their enemies, many had held extreme political views, and been involved in insurrections, revolutionary plotting and spreading of subversive social theories. But while the general suspicion of the Anglican church and state authorities, was that Baptists were basically dangerous extremists likely to do a ‘John of Leyden’ and introduce communism and bloodshed against the wealthy at the drop of a hat, many baptists were in reality quiet-living and law-abiding, so long as they could worship as they chose.

The range of ideas among the puritan and other sects was wide – many who sought independence from the established church for their own sect deplored tolerance for others (and catholics could basically whistle), but also feared and denounced the social rebelliousness that seemed to follow religious questioning. Many on the parliamentary side in the war were happy to enlist religious radicals to fight the king’s army, but had little intention of allowing this to imply the radicals had any right to either determine their own congregational path, or worse, start offering opinions on how wider society might be reshaped to the benefit of a wider swathe… A clarion call for freedom of conscience as a battle standard was a dangerous strategy, and it was to backfire on the cautious reformers and even many of the more devout leaders, as they saw subversive ideas spreading among the lower orders…

On the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, Robert Lockyer joined the Parliamentary Army (Roundheads) and served as a private trooper. It is telling that he joined the regiment commanded by Colonel Edward Whalley, having first served in Oliver Cromwell’s ‘Ironsides’: this regiment was filled with hardcore puritans and sectaries, who saw the struggle against the king as doing God’s work, but also debated and discussed among themselves, around campfires and on the march, the kind of society the Godly should help create. And by the mid-1640s they were coming to radical conclusions. Richard Baxter, a leading puritan preacher and theologian, chaplain to Whalley’s regiment in 1645-46, observed this, to his horror: “Many honest men of weak judgments and little acquaintance with such matters… [were]… seduced into a disputing vein… sometimes for state democracy, sometimes for church democracy.” Baxter would spent much time denouncing this kind of uppityness among the common sort, who ought to listen to the learned and stop thinking they had the right to question or offer up opinions of their own.

Some regiments in the victorious New Model Army elected Agitators or agents, who, in alliance with the London Levellers, drew up the Agreement of the People, a program for a widening of the electorate and some measure of social justice. Its four main proposals were to dissolve the current Parliament (suspected of lukewarm sentiment for change and many of whose members had been intriguing with the defeated king Charles to work against the power of the army), radically redraw constituencies to better represent the country, more regular elections, freedom of religious conscience, and equality for all before the law. (To this was added, in later editions, the vote to be extended to all adult male householders, and the exclusion of catholics from freedom of conscience. There are limits, after all.)

It’s not known when Robert Lockyer became a Leveller sympathiser, or whether he was heavily involved in the New Model Army agitators campaign for democracy of 1647, though it is assumed he was involved, as Whalley’s regiment was at the heart of this ferment. It was later said of Lockyer, after his death, that he had supported the Leveller Agreement of the People, and had been present at the abortive mutiny at Ware in November 1647, which had broken out as the more radical elements in the army began to realise that the leadership were outmanoeuvring them and had no plans to implement anything like as ground-breaking a program as the Agreement. The mutiny had followed on from two weeks of argument among the army leadership and agitators at the Putney Debates. Here the Army leadership made it very clear that they very opposed the idea that more people should be allowed to vote in elections and that the Levellers posed a serious threat to the upper classes. As Oliver Cromwell said: “What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces.”

Lockyer’s regiment was in fact stationed at Hampton Court, (guarding the imprisoned king, though Charles escaped on the 11th November), which was near enough for Lockyer to have ridden to Ware, (though he would have been AWOL at best, risking serious punishment if caught, up to the death sentence for desertion), if he was involved in the plans for a mutiny to impose the Agreement; but this may also be backward-myth making. We will never know. In any case the mutiny was quashed, as the majority of the troops present were persuaded to remain loyal to the Army Grandees, and Leveller/Agitator leaders Thomas Rainborough and John Lilburne realised that active support for a democratic army coup was weaker than they had thought. If Lockyer was present, it was not be the last mutiny he saw.

The Army leadership, represented most vocally by Oliver Cromwell, had ensured that the possibility of the army taking up arms against parliament on the basis of the Agreement could not happen, and in fact a Second Civil War followed as royalists rebelled in Kent and elsewhere. The threat in fact drove Grandees and radicals into temporary alliance against resurgent royalism and its sympathisers in a Parliament determined to put the army back in its place. But the rapprochement lasted only as long as the Second Civil War and the resulting purge of Parliament. When the king and his supporters were again beaten, Leveller demands for some quid pro quo for falling in behind Cromwell and co during this crisis, and rapidly led to the arrest of leading Leveller spokesmen.

This took place in early 1649. But the Grandees continued to pursue radicals in the army who attempted to push for the ideals set out in the Agreement of the People. In March 1649 eight soldiers from various regiments were court-martialled for petitioning the army’s nominal top brass General Fairfax to restore the more electoral structure the army agitators had briefly achieved two years before. The humiliating punishment five of them received – being paraded held up on a wooden pole, their swords broken, and then cashiered – made it clear that protest for democracy – in the army, or society in general – were not to be tolerated.

This formed the immediate background to the confrontation that cost Robert Lockyer his life. Future attempts by grassroots soldiers at independent action, on any issue, would be squashed.

A few weeks later, Captain Savage’s troop of Whalley’s Regiment, then quartered in the City of London, was ordered to quit these quarters and join the regimental rendezvous at Mile End, in preparation to march into Essex. On hearing this, 30 troopers seized the troop’s colours from the Four Swans Inn at Bishopsgate Street where it was stashed, and carried it to the nearby Bull Inn, a noted haunt of radicals at that time. Captain Savage demanded they bring out the colour, mount their horses and proceed to Mile End but they refused, fighting off his subsequent attempt to wrestle the flag off them. Lockyer told Savage that they were ‘not his colour carriers’ and that they had all fought under it, and for all that it symbolised (which could be interpreted in a number of ways, given the widespread debate about what the civil war had been for and how what many soldiers had felt were its aims had been closed down). Lockyer’s companions echoed his words, shouting ‘All, all!’

That a stance by just 30 men worried the army hierarchy can be seen in the quick reaction of Colonel Whalley and Generals Cromwell and Fairfax both hurried to the Bull. Whalley, arriving first with other regimental officers, and a large force of loyal troopers, negotiated with the 30 men. The ‘mutineers’ complained that they had not been paid enough to pay for the quarters they had been occupying in the city. This was a major grouse among civilians who housed soldiers in their homes – whether voluntarily, or in many cases, by force. The army was notoriously slow to cough up pay to its troops, sometimes arrears would run to months or even years, and the cost and inconvenience of quartering soldiers was a severe economic burden for householders. Seeing themselves as they did, as a kind of citizen army, the armed wing of righteous public opinion, some of the democratically-minded among the army were angry that they often could not pay their way, and this issue was a huge one at this time (not to mention the expenses mounted troopers like Lockyer’s company had for themselves – ie gear, horses, which often came to half their daily pay by themselves) . However, there is little doubt that both the 30 men and their superiors both saw this as the tip of a large iceberg, with all the repressed demands of the agitators and levellers looming threateningly below the surface. It was not what Lockyer and his comrades DID that required rapidly putting to an end – it was the potential for an insurrection that could spread to the city, and the wider army.

Although Whalley offered a sum of money to pay these arrears for quartering, the troopers pushed for stronger guarantees that he would offer, and Whalley lost patience, ordering Lockyer to mount, and when he refused, arresting him and fifteen of the other men. A crowd of civilians sympathetic to Lockyer and the rebels had gathered, but were scattered by men who obeyed Whalley’s order to disperse them. At this point Fairfax and Cromwell turned up, and ordered all fifteen to be taken to Whitehall to be court-martialled.

At the court-martial, one man was acquitted, three left to the discretion of the Colonel, five sentenced to ‘ride the wooden horse’ (the same punishment the five soldiers in March had suffered) – and six, including Lockyer, condemned to death. The six petitioned General Fairfax for mercy, promising to be obedient in future, and he pardoned five, but upheld the sentence on Lockyer. This was, Fairfax said, because at the court martial he had attempted to defend himself using the argument that their was no legal justification for the imposition of martial law (in reality, military control of the state) that the army grandees were operating under, in a time of peace – a clear challenge not just to daily gripes about pay but about policy and about whose interests the army were now representing. This defence enraged the court, and his death sentence was upheld not just to punish him, but to give an example to the alliance of army radicals and civilian activists that the Grandees feared was still active and brewing. A group of women supporters of the Levellers who had been visiting Parliament to petition for the release of the civilian Leveller leaders (ignoring the advice of MPs and Grandees to go home and mind their wifely duties and not meddle with the affairs of men!) had gathered outside the court-martial at Whitehall; they greeted the soldiers as they came out of the court, saying that there would be more such men as the accused in other places soon, and that Lockyer was a godly man and a Saint, who the authorities were going to murder.

The brief mutiny had aroused support among the discontented in London, and the possibility of a mutiny becoming an uprising had to be cut off. Whether Lockyer was in fact the ringleader of the protest or not, he was picked out to be a dreadful example for any potential rebels.

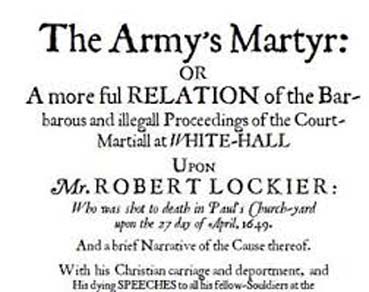

On April 27th, Robert Lockyer was marched to St Paul’s Churchyard by soldiers of Colonel Hewson’s regiment, to be shot. Speaking before execution, Lockyer is said to have announced

“I am ready and willin to dye for my Country and liberty and I blesse God I am not afraid to look death in the face in this particular cause God hath called me to.”

He added that he was happy to die if his fellows could be spared, but was troubled that he had been condemned for something so small as a dispute over pay, after fighting for seven years ‘for the liberties of the nation’. Refusing a blindfold, he spoke directly to the soldiers assigned to shoot him, “fellow-soldiers… brought here by your officers to murder me.. I did not think you had such heathenish and barbarous principles in you as to obey your officers in [this]” Major Carter, commanding the firing squad, being visibly shaken by this, Colonel Okey, who had been on the bench at Lockyer’s court-martial, angrily accused him of attempting to incite the firing squad to mutiny, and seizing his coat belt and jacket, distributed them to the firing squad, who then announced themselves ready to obey their orders. The sentence was carried out.

Lockyer’s funeral, two days later on Sunday 29th April, took the form of a political demonstration, a reminder of the strength of the Leveller organisation in London. Lockyer’s coffin was carried in silent procession from Smithfield in the afternoon, slowly through the heart of the City, and then back to Moorfields for the internment in the New Churchyard (underneath modern Liverpool Street Station – recently excavations here for the Crossrail train line has disturbed the bones buried here, presumably including Lockyer, and his fellow civil war radical, John Lilburne). The coffin bore blood-stained rosemary and a naked sword (a threat aimed at the Grandees of the potential for armed rebellion?)

Led by six trumpeters, about 4000 people reportedly accompanied the corpse. Many wore ribbons – black for mourning and sea-green to show their allegiance to the Levellers whose colour this was. A company of women brought up the rear, testimony to the active female involvement in the Leveller movement. If the reports can be believed there were more mourners for Trooper Lockyer than there had been for the martyred Colonel Thomas Rainborough the previous autumn, or king Charles a few months before. As the Leveller newspaper, The Moderate said, a remarkable tribute to a person of ‘no higher quality that a private trooper’ (quality meaning ‘class position’ here).

But while Lockyer’s funeral procession showed the strength of the support for the Levellers and sympathy with army radicals, Lockyer’s execution in fact showed that the Grandees were firmly in control of most of the army, enough at least to put down discontent and isolate troublemakers. Radicals in Whalley’s regiment were scared into submission, many signing a declaration of loyalty in May, and they did not join the subsequent army mutiny at Burford at the end of May, whose (again rapid) defeat marked in reality the end of any threat of an concerted army rebellion in favour of democratic ideals or Leveller principles. Three soldiers were shot 24 hours after the Burford mutiny, after another drumhead court-martial.

Written protest from Leveller spokesmen John Lilburne and Richard Overton, and a petition from Leveller women activists, at Lockyer’s execution fell on deaf ears – the Grandees were secure in the saddle, and knew it. They no longer needed the support of the radicals against the king or the moderate parliamentarians, and knew they could cow much opposition by executions, and ignore objections that martial law was no longer legal. They had also perceptively realised that their preparation to use terror and force was not matched by a similar determination on the radical side – as Colonel Hewson observed: “we can hang twenty before they will hang one.”

As with the other ‘radical’ army mutinies of the late 1640s, the way that Lockyer and many of his fellow soldiers saw themselves – as representing both the righteous of the nation, but also doing God’s work – gave them the justification for asserting their voice against their commanders; many of their commanders shared their background among the Saints, and so they also felt that this argument would be understood, at least. But diverging views as to what the interests of the nation and God’s work consisted of had been opening up since the beginning of the civil war – based on class interests, as much as interpretations of scripture. The actions of Cromwell, in particular, enraged the godly radicals, as they had seen him as one of them, a betrayer of the ‘good old cause’: but his class background meant his practical cleaving to the defence of the ‘men of property’ was always likely.

In the end, the program of the New Model Army agitators and the Levellers was forward thinking, and garnered wide support, but at a time of weariness of war, divisions and violence, not enough backing to push through into actual social change. The army mutinies all failed because, whatever widespread sympathy radical views inspired, only a minority were prepared to defy orders, whether for immediate grievances, or for larger social aims. Many of the reforms that the Levellers fought for, and Robert Lockyer and his comrades argued over in the army in the later 1640s, were later won, and are now widely help up as our democratic rights. Whether Lockyers of today would accept that, or push forward for more radical interpretations, for a wider redistribution of the wealth, power and responsibility in society… we can only speculate.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2018 London Rebel History Calendar

Leave a comment