The Southeast London ‘suburb’ of Thamesmead was built on land once forming about 1,000 acres of the old Royal Arsenal site that extended over Plumstead Marshes and Erith Marshes. Thamesmead was born in the 1960s, when the then Greater London Council developed plans for a new town to be built, to relieve London’s housing shortage and create a ‘Town of the 21st Century’. The name Thamesmead was chosen by a Bexley resident in a ‘Name Our New Town’ competition. The first residents moved to Thamesmead in 1968.

Thamesmead was designed around futuristic ideas, and indeed, looked impressive at first from a distance. Efforts were made to solve the social problems that had already started to affect earlier estates. These were believed to be the result of people being uprooted from close-knit working-class communities and sent to estates many miles away, where they knew nobody. The design of the estates meant that people would see their neighbours more rarely than they would have done in the terraced housing that had been typical in working-class areas. The solution proposed was that once the initial residents had moved in, their families would be given priority for new housing when it became available.

Illustrating the utopian (though imposed top-down) dreams of the planners of the estates, many of the blocks and roads were named after the great Liberal social engineers and theorists of the 19th and early 20th centuries: the Booths, Octavia Hill, JS Keynes, the Webbs, JS Mill, Jeremy Bentham. (by the 1990s, residents were entitled to feel themselves the butt of this liberal joke).

Another ‘radical’ idea of the GLC division architect Robert Rigg thought sounded funky was drawn from housing complexes in Sweden, where it was believed that lakes and canals reduced vandalism and other crime, mainly among the young. Rigg designed various water features, including a lake, and incorporated a pre-existing canal, to impose a calming influence on the residents.

The area had been inundated in the North Sea Flood of 1953, so the original design placed living accommodation at first floor level or above, used overhead walkways and left the ground level of buildings as garage space.

The first flats were occupied in 1968, but problems developed rapidly. Early on flats suffered from rain penetration problems. Walkways stretched between its blocks of housing and later between sections in North Thamesmead. But the walkways quickly became littered and abused, and became considered unsafe places to walk. Pathways set out for people to walk on were laid with little regard to how people would really move about, so some were ignored in favour of more direct routes over grassed areas.

When the GLC was abolished in 1986, its housing assets and the remaining undeveloped land were vested in a non-profit organisation, Thamesmead Town Limited (TTL). TTL was a private company, though its nine executive directors were local residents; they periodically submitted themselves to re-election.

Split between two boroughs, Bexley and Greenwich, Thamesmead became somewhat frozen, under-resourced and bleak: “The Town Centre, clearly marked on sign-posts, is cynically named. Actually it’s just a few acres of Safeway on the very edge of town, a skerry incapable of supporting human life, torn from the nearest flats by a main road, and more than two miles from Thamesmead’s middle. In the late Eighties a gabled clock tower was added so that, from the river, it looks like an old market town. The clock stopped at twenty past two some time ago.”

The most significant design failure was the almost complete lack of shopping facilities and banks: only a few “corner shops” were initially built at Tavy Bridge. From the start Thamesmead was cut off from Abbey Wood, the nearest town with shopping facilities, by a railway line; however a four lane road bridge was built over the railway in the early 1970s. The area was then cut in two by the A2016, a new four lane dual carriageway by-pass of the Woolwich to Erith section of the A206 (although for years this road only got as far as the industrial part of lower Belvedere: the extension to Erith was opened in 1999). Still, residential building continued, this time on the other side of the A2016, which cut this part of Thamesmead off from rail travel to central London. The planned underground station never arrived.

Over time more facilities developed, with a Morrisons supermarket and retail park near Gallions Reach. Bus services were improved and residents can now easily reach Abbey Wood railway station.

The conditions on the estate bred many problems… some ongoing.

London like other uk cities had a number of similar areas, sometimes out on the edges, often, as with Thamesmead, older white residents or those living in adjacent areas had been white flighters a few years earlier, leaving inner city neighbourhoods for new towns, partly because there were ‘too many foreigners moving in’.

The estate’s population was always overwhelmingly working class, initially mainly white, drawn from older areas across South London, but increasingly Afro-caribbean and later African communities. Many of the industries in surrounding areas which had employed Thamesmead residents closed down, went out of business or moved in the 1970s and 80s, and unemployment rocketed. The estate became to some extent a dumping ground where families were rehoused, without resources or much chance of leaving. “Thamesmead was abandoned, half-finished. The people who live there, imprisoned by the ring-roads and the roundabouts with exits that lead nowhere, can’t easily escape. They say they live on Thamesmead, not in it, as if it’s an island, a penal colony.”

The area was riven in the 1990s by racial tension – mainly harassment of black residents by a number of their white neighbours, but complicated by a youth gang culture which to a limited extent crossed ‘race’ lines, but also mingled with racists at one end of its spectrum.

Racism among some white Thamesmead inhabitants was supported and aggravated by the influence of organised fascists, centred on, but not limited to, the British National Party, then a small neo-nazi grouping (though later to grow & become more populist) who then ran an infamous bookshop in nearby Welling, set up in 1987. This shop was linked to the spread of violent nazi ideas, and an upsurge in racist attacks, in large areas of South East London and North Kent, and wider afield; but the organised right was also able to meet and operate from a number of other places, such as the Abbey Mead Social Club, a haunt of some BNP members and adherents of another nazi group, the British National Socialist Movement. BNP ‘faces’ drank in the Horse and Groom Pub in Charlton, attempting to whip up racism among Charlton Athletic fans. In Thamesmead itself, racism centred on the Wildfowler pub, where a number of local racist residents and friends hung out. Black people were effectively barred from the pub. Harassment of black residents, beatings, knife attacks, were a regular occurrence around the area.

But the influence of the BNP and other overt fascists was a matter of debate at the time – not only because racism among many white residents was more ingrained, but also because the climate of national policy, media and government approaches had played a significant part in creating both a climate of hostility to minorities, and a sense of abandonment and despair which turned into anger, resentment, and fuelled gang violence, as well as the scapegoating of ‘foreigners’ for taking our jobs and houses, blah blah. Failures of state and left responses to these developments generally only compounded the situation.

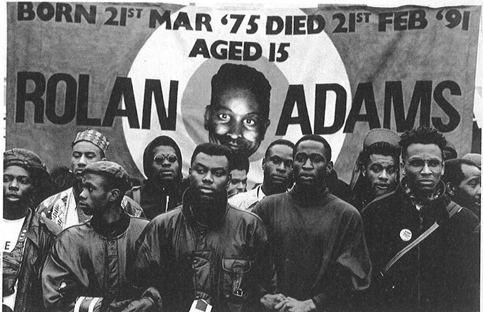

In early 1991 things came to a head in Thamesmead. On February 21st 15-year old Rolan Adams and his younger brother were walking home to Abbey Wood across the estate from a local youth club, when they were attacked by a gang of young white racists, from a Thamesmead gang calling themselves the NTOs – standing according to them for Nutty Turnouts, though others claimed it really meant ‘Nazi Turn Outs’, (they were also known as the Goldfish Gang, or later just the Firm). Rolan was stabbed in the neck and died.

A few weeks later, on May 11th, Orville Blair was stabbed to death outside his home in Thamesmead; some claimed this was a gang murder, not racist at all, as Orville Blair may have been at some point associated with the NTO. Some of the NTO were interviewed at this time, claiming they were not racist and had black members, and were at war with rival gangs, notably the ‘Woolwich Mafia’, a predominantly black but multi-racial gang from neighbouring Woolwich, which had allegedly not only been trespassing on NTO turf, but also winning allegiance from Thamesmead black kids (very likely out of fear of local racists).

But the second murder ratcheted up an already fierce tension on the estate. Around 100 racist attacks were reported in the area in the first few months of 1991. Several black families, including some who had vocally opposed racism or confronted the NTOs, asked to be rehoused off the estate and were moved. The Hawksmore Youth Club, which had attempted to organise anti-racist events, was firebombed – and then helpfully closed down by the council, giving the arsonists a pat on the back.

A campaign against racist violence sprang up in the area, following the murder of Rolan Adams. A packed public meeting was held (police representatives were angrily ejected from this meeting, as people had little confidence in the figleaf of police protection). A militant and angry demonstration was held on 27th April, which saw some 1000-1500 people march round the estate, and then marched on to the BNP bookshop: “When we reached Welling, the anger erupted, and hundreds brought the march to a halt… The Nazis kept wisely out of sight, and it looked for a moment that we we’d all go home with a brick out of their wall as a memento, but the police and others came to the rescue…”

It was among local black youth that the initial angry response had developed, but increasingly a plethora of organisations got involved, with the stated aim of supporting anti-racism in Thamesmead and opposing both BNP influence and the wider culture of racism. Anti-racism and anti-fascism were growing in support generally, but these diverse movements were riven by many factions and splits; some organisations wanting to rely on police and state solutions (flying in the face of the these very institutions’ involvement in creating the social problems and tacitly encouraging racial violence), others fronts for left groups, opportunistic at the very least and inconsistent or cynical much of the time; there were others who labelled all white people as the problem, and ignored the anti-racist feelings or actions of any white working class people in Thamesmead and elsewhere, which did tend to add to the widespread alienation and increasing division. Meetings tended to end up as dogmatic rows between different factions, and campaigns quickly could become paralysed by this. Actions proposed by some would always be denounced by others, sometimes on sectarian grounds, sometimes simply to be seen to be saying something; though there were genuine political differences and some useful critiques, but amidst all this, much energy that should have been directed at defeating fascists and opposing racism was spent in backbiting. Anyone who spent time involved in opposing racists and fascists around this era is likely to recognise these dynamics.

In Thamesmead specifically at this point the angry campaign meetings organised initially by local black youth had become a debating ground for various groups, including The Greenwich Action Committee Against Racist Attacks (Gacara for short – a local group monitoring and campaigning around racist attacks borough-wide), trotskyite left group the Socialist Workers Party, Anti Fascist Action, (an alliance of socialists and anarchists who advocated physical resistance to fascism – beating them off the streets – well as politically winning white working people away from racist ideas), as well as the National Black Caucus, a black political grouping. Arguments had begun to prevent action. Anti Fascist Action noted: “One local pub in particular, the Wildfowler, was identified as a meeting place for the racists and the fascists who inspire them. Immediately after [the first campaign meeting on the estate] a posse went down to the pub to let the landlord know the score and to challenge what was described in the meeting as an unofficial colour bar. It was a successful first step in a campaign aimed to either get the fascists out of the pub or to close it down… the pub should be a facility for everyone in Thamesmead, or it should be a facility for no-one…

However, before any of this could happen, some of the people from the meeting, including some of the people from the Socialist Workers Party who had made rousing speeches about fighting racism ‘by any means necessary’ set themselves the task of talking everyone out of the idea of going to the pub at all… They lost the argument… It showed that they could be very good in meetings but not so handy when it comes to putting words into action… some of these characters will even go to the lengths of actively dissuading others from taking action…”

The pub drink also illustrated which side the police were keen to take: “despite the fact that there was no question of violence or disruption – it was a peaceful drink, the first time in a long while that blacks could have a peaceful drink in the pub – the police very soon appeared and emptied the pub of anti-racists. Then, out on the street, they set out to provoke incidents with the local youth – they were itching to wade in and make arrests.” All too often the cops were happy to let racists carry on – as you were – but batter and nick anyone who attempted to resist this, whether ‘violently’ defending themselves against racist attack or peacefully occupying a pub.

Others involved in the campaign at the time grew aggravated at the diversion of anger into tokenism: “The campaign meeting in the week after the march brought out many of the problems. The Socialist Workers Party’s only contributions were to propose an anti-racist concert in June and a pocket of the Tory-controlled Bexley Council… They tried to rubbish any talk of self-defence as terrorism.” However, Anti-Fascist Action’s stance also took some flak: “AFA talked about defence purely adventurist and elitist (‘we will protect you’ ) terms – which leaves the local community dependent on their mobilisations…” This critique, from a small, black-led trotskyist splinter called the RIL, does overly caricature AFA’s position, but had an element of truth, in that AFA tended to concentrate on physical intervention in specific arenas, but this didn’t always help with building a longer term more grounded grassroots resistance. Which all would admit is more complex than shouting slogans and running away. However, AFA criticised most of the other groups as posturing without any sense of how to draw white working people, the fodder for BNP propaganda, away from racist ideas. Which was always true and has remained so – catastrophically so in some parts of Britain. GACARA were broad-based, but had links to the Labour Council in Greenwich, who many thought bore some responsibility for the shite conditions on the estate which fuelled much of the violence there. Almost everyone involved in the Thamesmead campaign noted that the people mostly ignored were the local black youth who had started the fightback, who (as elsewhere) found themselves marginalised by the squabbling lefties. In response some set up the Thamesmead Youth Organisation, which gathered some of the most active local youth and tried to combat racism while demanding that the local councils improve facilities…

While some in the NTO Thamesmead gang denied that they were inspired by the BNP, the BNP themselves did want to get involved… The growth of the BNP from nazi fringe loons, to the bigger racist populist organisation they would become a few years later, was only really just beginning then; and they were still less concerned with public relations and concentrated more on legitimising racist violence and playing on fear to build up hatred. They saw the two deaths and the wider attacks as evidence for their campaign that ‘multi-culturalism doesn’t work’ – ‘black and white people couldn’t live together’. Their nasty rhetoric may or may not have always directly inspired racist attacks, and they were not directly involved in ALL cases of racial violence (though they were in some), since racism was widespread throughout local white working class populations, and violent expressions of it didn’t necessarily need the BNP’s hand… But the BNP seized joyfully on the situation, beginning to spread their nazi propaganda around, and announcing a ‘Rights for Whites’ march through Thamesmead for May 25th, claiming they had been ‘asked by white residents’ to defend them against ‘black muggers’. The ‘Rights for Whites’ theme was a big BNP push, as their propaganda made a big thing that ‘white British people’ were being oppressed in their own country and had no rights while ‘blacks, gyppos, pakis and other darkies’ were getting special treatment in terms of housing, jobs, human rights etc. This was blatant nonsense, since white racism still allowed discrimination on all levels of society, and official equalities policies masked hatred of minorities in the police, local government, national policy. However it had an appeal to a disgruntled strata of working class whites, wondering where the jobs had gone and left adrift by social change – as well as to the empire-nostalging and eugenically-inclined, of various classes…

The BNP Demo on May 25th was opposed by a strong contingent of anti-racists and anti-fascists. Even top cops in the Met pointed out that allowing the march to go ahead was deliberate provocation; this didn’t prevent them from using a fair bit of trunch on the day to protect 150 or so BNP members (around its realistic away crowd then) from a much larger angry crowd of anti-racists. A number of fascists who turned up late were caught and battered by anti-fascists. But despite a decision taken in the campaign meetings to physically attempt to confront the BNP march, on the day the main campaign organisers (by now backed by the SWP and National Black Caucus) backed off from this and led people in the opposite direction, just as the BNP march was entering the area, and ignored protests that this was against what had been decided at the planning meeting.

“This decision was not supported by all present – in addition to AFA and a substantial number of local youth, Searchlight supporters and even some individual members of the SWP refused to go along with the last minute about face.”

Thamesmead being designed like the warren it was, there were a hundred back ways, alleys, bridges, paths, which could have been used to bypass the police and confront the fash; in the end only part of the crowd attempted to do so. Bar a bit of running after stray Nazis and some provocative kids, the day came to a frustrating end.

Anti Fascist Action’s position was that this was a wasted opportunity and had strengthened the hand of the BNP: “The issue facing anti-fascists in Thamesmead is a clear one: do we want a token campaign which expresses our opposition to the BNP and racism, but does not actually confront the fascists, or do we insist on concrete action against specific targets?” This question had come up before and would come up again. The BNP in South/Southeast London certainly felt stronger, and would try to build on this through the summer of 1991, standing in a council by-election in Camberwell in July, and stepping up a regular presence in Bermondsey.

Their bookshop/HQ in Welling would remain, despite regular demonstrations demanding its removal – the fash were helped by tory Bexley Council, who steadfastly opposed racism by, er, refusing to do anything at all about the Nazi shop. Although there were constant arguments among anti-racists and wider commentators about how much racist violence in Southeast London was caused by the shop’s presence, or whether the BNP were a symptom of a wider racist culture there, there is little doubt that the flood of fascist propaganda the BNP had put out continued to have some effect, encouraging serious racial attacks. In any case, racist attacks and racist murders increased. 16-year old Asian Rohit Duggal was murdered by a gang of ten white men in July 1992; In July 1992, Rohit Duggal was stabbed to death by a white youth outside a kebab shop. The killer, Peter Thompson, was found guilty of murder. He was said to have links to a racist and criminal gang around Neil Acourt, who carried out a number of attacks on black youths in 1992-3. The attack came a year after the stabbing of another man outside the same shops. Police said there was ‘no evidence of a racial motive’, which was bollocks, but then Neil Acourt’s crim dad had several dirty cops in his pocket, so…

Kevin London, a black teenager, claimed he was confronted in November 1992 by a gang of white youths, including Acourt’s mate Gary Dobson, who was armed with a large knife. The claim came to light only after the killing of Stephen Lawrence. No charges were laid.

In one week in March 1993, two men were stabbed in Eltham High Street, with witnesses describing members of the Acourt gang. The following week, a white man, Stacey Benefield, was stabbed in the chest. He identified David Norris as the attacker and Neil Acourt as being with him. Norris was the only man tried. He was acquitted.

Acourt and Dobson would of course become notorious, as in April 1993, they together with several other white men, murdered Stephen Lawrence in Eltham. This killing did focus a national spotlight on southeast London and would lead to the Lawrence Inquiry and far-reaching public relations changes to how the police allow themselves to appear.

The campaign against the BNP bookshop would reach a peak with a massive demonstration to Welling in October 1993 which would end in a police ambush and serious fighting, between police and demonstrators. 31 demonstrators were arrested and several jailed. Eventually overwhelming pressure led to Bexley Council being force to set up a planning inquiry and the shop closed down.

The Socialist Workers Party, after years of telling AFA and other anti-fascists that Nazis were a tiny irrelevant fringe, shortly after the Thamesmead events, began to change their position, and re-founded the Anti-Nazi League, which they had also been movers in back in the 1970s. The ANL mark 2 made a big splash, carried lots of lollipop placards, and ran around a lot.

A short history of Anti Fascist Action

Racism and fascism seems to be alive and well.

A postscript

Only one man was convicted of murder for the attack on Rolan Adams and his younger brother Nathan (who escaped with his life): Mark Thornburrow was jailed for a minimum of 10 years. Four others were given community service for violent disorder. Rolan’s father Richard Adams said there was unwillingness by police and prosecutors to go after anyone else for the killing.

In 2014 it was reported that the Metropolitan Police had admitted to Richard Adams that its now disbanded Special Demonstration Squad had spied on him and other members of the Adams family and campaign, as they did on many other black justice campaigns.

It’s unknown if any of the information collected on Rolan Adams’ family was harvested by any of the three spycops described by Peter Francis, an undercover cop working for the SDS who infiltrated Youth Against Racism in Europe (YRE), an anti-racist front for the trotskyite Militant Tendency (now the Socialist Party) which, along with the Socialist Workers’ Party-run Anti-Nazi League, had largely organised the Welling demonstration in October 1993, there were police spies operating that day – on both sides.

Seven of the ten police spies then (admitted to be) active from the SDS were “sufficiently embedded in the right political groups to supply intelligence in advance of the demonstration.”

As well as Peter Francis (spying on YRE as Pete Black), another SDS police officer was involved at a high-level with the SWP-controlled Anti-Nazi League. Interviewed for Rob Evans and Paul Lewis’s book, ‘Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police’, Francis observed the actions of his colleague as the riot developed: “There was a moment when I am a SDS officer going forward with my group, and there’s another SDS officer in the Anti-Nazi League running backwards, calling on the crowds to go with him away, trying to get people to follow him.”

The book also claims, in the same chapter, that an undercover cop was involved with Combat 18, a so-called ‘neo-nazi’ group, later widely regarded as a Special Branch honey trap for unsuspecting right-wing activists, and claims: “A fourth spy was actually inside the BNP bookshop. For some time, he had been a trusted member of the party. He and others were expected to defend their headquarters in the event the crowd broke through the police lines and started attacking the building. ‘He was bricking it,’ Black says. ‘We had to protect the bookshop that day as Condon (the Met’s commissioner) knew that there was an undercover police officer in there.’”

Nice to know Special Branch were on both sides… how much the four respective SDS operatives manipulated the struggle around racism and anti-racism, remains unclear, possibly not very much… some SDS spies limited themselves to collecting intelligence, a few tended to be a bit more agent-provocative. Certainly there was speculation at the time of the march that the Met had desired a violent confrontation to allow them some extra leeway for breaking heads. The October 1993 Welling ‘riot’ was suspected by some of us suspicious types at the time to be set up to play into police hands – though conspiracy theories are always to be avoided if possible, you can’t help wondering now whether the SDS were serving a wider police agenda in having the demo walk into a police riot. SDS head Bob Lambert certainly helped the Met out with info from the undercovers concerned when the Stephen Lawrence enquiry into police and other institutional racism was threatening to make them look very bad indeed. Perhaps all the details will come out in the Undercover Policing Inquiry – though given the current police obstruction tactics preventing anything on the Inquiry from moving forward at all, probably not.

There is more interesting background to the racist gangs, links to crime families, and corrupt relations with the police, here

The above was written partly from personal recollections, though some bits of ailing memory were refreshed from Wikipedia, Anti Fascist Action’s magazine Fighting Talk, CARF magazine, Gacara’s Report 1992-3, and Revolutionary Internationalist. On May 25th 1991 the author of this post was a spotter on a bike riding round the estate to keep tabs on the movements of fash and police and report back to anti-fascists. Other memories and views would be welcomed.

Rolan Adams’s grandmother, Clara Buckley, was also the mother of Orville Blackwood, killed in Broadmoor High Security Hospital in August 1991. A powerful woman who never gave up fighting for justice.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2017 London Rebel History Calendar – check it out online.

Leave a comment