In the mid-1980s, sick of the right-wing bias of the press, a group of Uk leftwingers decided, instead of complaining about it, they would set up our own newspaper: “a radical, campaigning tabloid that would speak truth to power.”

Thus was the News On Sunday born. It lasted 6 weeks.

Below we reprint an account of the birth and death of News on Sunday, which we have unscrupulously nicked from the Big Flame history blog. Sorry, but theft comes natural. The account does emphasise former Big Flame members’ role in the paper, but others were involved…

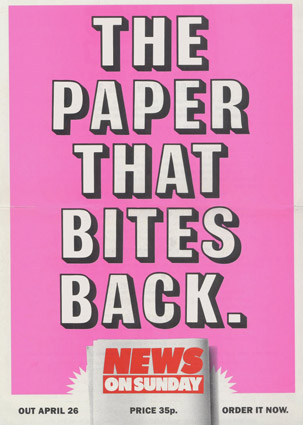

“Possibly the most ambitious project to come out of Big Flame was News on Sunday. The aim was to set up a radical campaigning tabloid Sunday newspaper, to challenge the right-wing domination of the media. It was created, and launched on 26th April 1987. We raised £6.5 million. And lost it all in 6 weeks, though continued to publish for a further six months – funded by the TGWU in partnership with the eccentric millionaire Owen Oyston.

The idea came from Ben Lowe, and was first set out in the Big Flame discussion bulletin in 1978. His idea was to go beyond the ambitions of newspapers like Socialist Worker and the Morning Star and establish a paper that was a popular tabloid – selling in the newsagent alongside the mainstream press. His belief was that, if we could establish sales of 100,000, it could be commercially viable. He was to be joined by Alan Hayling (a long-time Big Flame member who had been a TV producer before going to work at Ford on the assembly line), who fronted the project, built alliances and co-ordinated the raising of the funding that made it possible.

By this time Big Flame had dissolved but this was certainly a project inspired by the ideas of BF. Many other projects inspired by left-wing groups did happen then, but News on Sunday was probably unique in the scale of its ambition, as shown by the £6.5 million needed to make it happen.

Alan and Ben brought together a range of people on the left, inspired by the idea of taking on the mainstream media rather than just complaining about it. All working for free, and with no promise of any reward, a rather good pilot edition was produced in the Autumn of 1985.

With persuasive market research – on the basis of the dummy edition – and a strong business plan, Alan persuaded Guinness Mahon (a City of London merchant bank) to take it to the city. But the mainstream City investors could not understand it. “Where do the founders make their money?” was a common question. I don’t think we ever consider making money out of it – not beyond a basic salary. That wasn’t our motivation, we wanted to change the world. To most city investors the lack of a financial incentive was just weird and they were out. (It was the equivalent of going on Dragons Den and asking for a large amount of money, but then saying they could have 100% of the shares.)

I was one of the group known as the Founders (though I stepped down when I was employed on the paper). Although the newspaper was owned by the shareholders, the Founders held a Golden share, designed to protect the values of the paper and prevent a takeover by the likes of Murdoch or Maxwell.

We also, over many months, set down the political charter on which the newspaper was to be based. This was intended as the guiding principles. The idea was that just as every journalist on the Mail knows, almost intuitively, the Mail angle on any story so would any journalist on News on Sunday know the angle to approach news from. In practice, though pinned up around the office, it was largely ignored and people went with their gut feeling – which was sometimes a radical and alternative interpretation and sometimes wasn’t.

The Independent had just succeeded in raising the investment it needed and it always struck me that there was a far less clear gap for that newspaper than for a radical Sunday tabloid. It seemed very unfair that the city had been prepared to back it simply because of the experience and the authority of the management team, but not to back our project. Sadly, they turned out to be right.

The money was raised from trade unions, from individuals and – the majority – from local authority pension funds. To my mind this was the Big Flame approach at its best – building bridges, working imaginatively and with great ambition. And there was no subterfuge. We laid out very clearly, in the Charter, what the paper was about. Core to our argument was that it could only succeed commercially if it was genuinely radical. I always described it as a left-wing version of the Mail on Sunday. I remember Ron Todd (General Secretary of the TGWU, who invested £550,000) questioning the position on Ireland, which called for British withdrawal. He was won round after Alan pointed out that this was exactly what a recent Daily Mirror editorial had called for.

I remember well the party on the night where the offer closed and we had succeeded, we had raised £6.5 million. So many on the left had told us it could not be done but we had worked with the system and raised the money. It was an incredible moment.

If that was the Big Flame approach at its best, we were about to see the approach at its worst. The revolutionary left, Big Flame included, was oppositional. It campaigned against things. We had no experience of organising anything except political struggles. I could check with ArchiveArchie but I doubt there was a single article in the Discussion Bulletin, over more than a decade, on how to manage an organisation.

Shortly after publication, as the crisis hit, a ‘company fireman’ called Roy Barber was called in to sort things out. I remember him being very puzzled. “I get called into companies in crisis and normally I find de-motivated people who are really not very good at their jobs. Here you have highly motivated and talented people – and yet you are heading for bankrupcy.”

Those involved will point to many explanations of what went wrong. Some say it was because John Pilger (involved during the dummy period) was pushed out, some that it was because of his behaviour. Some that we should have been based in London, not Manchester. Some blame Alan Hayling. Some blame Keith Sutton, the man we hired as editor (after he produced the strikers’ Wapping Post during the Times newspaper strike). Some blame the advertising agency with their inflamatory slogan “No tits but a lot of balls”.

I believe we created an environment in which it was impossible to succeed. It was full of endless meetings, back-biting, lack of clear responsibility and a sense of blame if you got things wrong. The debate over “No tits” became so heated that there were groups of people who wouldn’t talk to you if they suspected you of supporting it. You had to watch what you said and who you said it to. It was, with hindsight, what you would expect if you put a group of 80s lefties in charge of running an organisation. And I include myself in that.

When Vanessa Engle (who worked as an editorial assistant at News on Sunday) was producing the BBC2 programme on the newspaper, she asked when I knew it would fail – imagining I would say 26th April 1987, the Sunday of the first issue, when we realised how low the sales were. I replied that it was two months earlier. It was the end of a heated day of meetings when we had decided to pulp £85,000 of posters that were ruled unacceptable. I walked round the block and wept, for I knew then the newspaper could not succeed. It wasn’t even that I liked the posters. But I knew an organisation that was capable of agreeing to commission and spend this amount of money, and then – in its schizophrenic decision-making structure – decide to ditch it, could not succeed.

We, those who set up the newspaper, took over the management and hired a group of journalists. I often think it would have better to do the opposite, to hire a group of managers and take positions as journalists. Many of us knew how to write, as we showed in the dummy. And we knew very clearly the radical angle we wanted to put on the news. We had no idea how to manage.

The result is best expressed in the title of the book about News on Sunday, “Disaster” (by News on Sunday journalists Peter Chippendale and Chris Horrie). The advertising – the TV ads and posters – that survived the internal rows was feeble. An argument with retailers over the % of the cover price they received resulted in lack of enthusiasm on their part. And the paper itself, in my view, lacked the radical political bite that we had envisaged – and had succeeded in producing in the dummy.

The paper only rarely lived up to our hopes and was often hard to distinguish from competitors like the Mirror and the People. I remember one shameful cover story ‘exclusive’ proclaiming that a convicted rapist was to be freed because his victims had been found to be prostitutes. The article, from any radical perspective, should have been asking why that made any difference. It was published from this angle because we had got hold of the transcript, not yet made public, and so were first to reveal this information. (And, in fact, the transcript revealed that the judge still regarded him as guilty but he got off on a technicality.)

On Ireland I did manage to get a freelance journalist commissioned form the North, who could give the nationalist perspective and had great connections with the Republicans. Her first artic le, published in one of the pre-publication dummies, was hard hitting. But then I discovered it was, word for word, the same article as she had written for An Phoblacht, the Sinn Fein weekly newspaper. She couldn’t understand why that was a problem and wouldn’t agree to write different articles for us. It would have made News on Sunday an easy target for some.

After the SAS killed 8 IRA men in an ambush I did write an editorial asking whether eight more mourning families would make peace more likely. To my astonishment Keith Sutton published it. (I had joined the project partly because of my desire to be involved in journalism but this was the only thing I ever wrote for News on Sunday.) But after that the Ireland coverage reverted to the media norm of British troops versus the terrorists.

By the time of launch the costs had ballooned to the point where News on Sunday needed to sell 800,000 to break even. This was a long way from Ben’s original hope of 100,000 but, given the market research sales predictions of over 1 million, didn’t seem at the time to be a problem. It would be interesting to see what we would have created if all our plans had been based on a break even at – say 250,000. A tougher business person could have insisted on it.

In week 1 it sold barely half a million and we knew it would go down from there, as all new launches did. Owen Oyston, a Lancashire multi-millionaire who had made his money in estate agency, was already an investor and stepped in to try and rescue the paper.

The 1987 general election was imminent and it seemed for a time that if the newspaper, funded by Labour local authorities, went bankrupt in the middle of the campaign it would be a gift to the Tories – as a great example of “loonie lefties” in action. Oyston went to see Neil Kinnock, leader of the Labour Party. I don’t know what happened in the meeting but Oyston believed he was promised a knighthood if he could keep the paper going until after the election. With the TGWU he put in more money and the bankruptcy was delayed until the week after the election. The paper staggered on for four more months, owned and funded by Oyston and the TGWU.

I was by then Finance Manager and I remember bizarre trips to his mansion (where bison wandered the gardens) to have payments approved. Oyston was a strange character, for whom the newspaper – fresh off the press on a Saturday night – would be delivered by models from a local agency. He is better known now for the prison sentence he was to serve for rape.

I also came across a list of payments to local politicians, including £3,000 to somebody who is now a prominent North-West MP. It may have been perfectly legitimate but, when he discovered I had a copy, he went to great lengths to get it back. It was a sad end to have him in charge of our great idealistic project. I eventually left the newspaper, before it went bankrupt a second time, after refusing to sign the cheque to the model agency for ‘consultancy’. The head of the agency was later to go to jail with Oyston. It was a very seedy business.

The Golden share had proved to be no protection. Faced with the financial crisis and an ultimatum from Oyston (“give up the golden share or the paper closes”), the Founders had no alternative but to give in and hand over control.

After I left News on Sunday I set up a training business, now called Happy Ltd. When I am asked what motivated me to start Happy, I always refer back to News on Sunday. The greatest irony for me was that, for all our ideals, it was a far worse place to work than IBM – the great capitalist monolith where I worked in my year off. I left determined to find out how to create a company that was both principled and effective – and a great place to work in. I learnt most of what I know about how not to manage at News on Sunday.

We had great dreams. We would show it was possible to engage with the capitalist system and create an alternative within it. We succeeded in raising millions and, if we had succeeded, we could have set an example for others to follow. Instead we made it virtually impossible for a similar project to get funding again (though the actual amounts the pension funds lost was dwarfed by the losses caused by the crash of October 1987.)

And we didn’t even manage to create a publication that was especially radical or challenging. And, to me, that was down to our lack of ability in how to manage and organise to get the most from our people.

It could have been a truly great legacy of Big Flame. In fact those of us involved from BF did not play any separate role and certainly didn’t have a caucus of any type. We did have strong views on what should go in the Charter, meant to be the guiding document for the publication, but had no common view on the key question of how to build an organisation that could create a great paper – or the experience to make this happen.”

Henry Stewart, September 2010

Note on Big Flame

Big Flame were a Revolutionary Socialist Feminist organisation with a working class orientation in England. Founded in Liverpool in 1970, the group initially grew rapidly in the then prevailing climate on the left with branches appearing in a number of cities. One of the key sentences in the platform published in each issue of the newspaper was the statement that a revolutionary party was necessary but that “Big Flame is not that party, nor is it the embryo of that party”. This had the advantage of distinguishing them from some small groups who saw themselves as much more important than they were, but posed the problem of the ‘party’s’ real reason for existence.

They published a magazine, also entitled Big Flame, and a journal, Revolutionary Socialism. Members were active at the Ford plants at Halewood and Dagenham. They also devoted a great deal of time to self-analysis and considering their relationship with the larger Trotskyist groups. In time, they came to describe their politics as “libertarian Marxist“. In 1978 they joined the Socialist Unity electoral coalition, with the International Marxist Group.

In 1980, the anarchists of the Libertarian Communist Group joined Big Flame. The Revolutionary Marxist Current also joined at about this time.

However Big Flame was wound up in about 1984.

Much more on them here

For the fun of it: a TV ad for News On Sunday. Yes, it is bad.

Read about another attempt at a radical tabloid: the Scottish Daily News

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2017 London Rebel History Calendar – check it out online.

Leave a comment