“A desperate fray happened at Wapping among several gangs of coalheavers; many persons were wounded, and several houses almost destroyed.” (Annual Register, 15th April, 1768)

Ah, ’68… year of riot, uprising and turbulence… No 1768, not 1968…

London, in 1768, seemed poised on the brink of apocalyptic revolt, as hunger, poverty and political agitation almost merged to give birth to revolution… Like 1381, 1649, 1780, 1889 during the dock strike, or 1919, was it a possible ‘revolutionary moment missed’, as we once wrote in a calendar? This may be going too far, for 1768, but it’s true that a number of movements came together, or co-existed, striking fear into the authorities, taking control of the streets, and one dispute or flashpoint would influence another, like wildfire…

On the political level ’68 was a year of mass agitation and crowd violence in support of John Wilkes, the rakish journalist, a scandal-mongering champion for reform of the political system, who won support from both the City of London merchant elite and the ‘Mobility’, the swelling, insurgent and always altering London mob. Wilkes had already been jailed and banished for challenging the establishment; in 1768 he was standing for election to Parliament for Middlesex, the huge (consistently politically progressive) constituency north and west of London, near enough for huge crowds to flock there and support him, leading to riots at the hustings, and assaults on Wilkes’ pro-government opponents. But his views got him barred from entering the house of Commons, even when elected (he was to be ruled ineligible several times, but re-elected each time). Pro-Wilkes marches became pitched battles, demonstrators were shot by the militia, Wilkes was imprisoned…

But 1768 was also a year of starvation: “the price of bread had doubled. The price of meat had increased by a third. Crowds forced street-vendors to sell vegetables at reasonable prices. The Whitechapel butchers ‘suffered prodigiously’. Elsewhere, butchers ‘were oblig’d to secrete their meat’. Corn-factors were attacked and their wagons stopped. The corn-dealers hid their plate, boarded up their coffee-houses, and closed the Stock Exchange…”

As rising food prices sparked protests, a wave of disputes swept London, especially in the East End, over wages, over working conditions and how work was regulated and controlled. Trade after trade erupted into stoppage and demonstration. “The sailors and the glass-grinders petitioned, shoemakers held mass meetings and the bargemen stopped work. The leaders of the tailors were imprisoned for ‘Irritating their Brethren to Insurrection, abusing their Masters, and refusing to work at the stated prices.’”

The political and economic turbulence mingled and sometimes merged; many of the workers in the London trades supported Wilkes, and marched for him… Though he was only ever mainly interested in the promotion of himself, and his image as the outrageous critic of the monarchy and government, darling of the mob, and would always balk at encouraging violence. He would end his days as comfortably, and almost respectable, having served as MP, alderman, Sherriff and Lord Mayor of London, (where he admittedly did work to improve legal protection for prisoners, servants and workers) and taken up arms to command soldiers to shoot down his former supporters attacking the Bank of England during the Gordon Riots. It’s not just the ‘reactionary populists’ we need to beware of…

To add to the fears of the ruling classes, there was talk of unrest in the army: “Soldiery may become a political Reverbatory Furnace”. If a regime loses the army, revolt can become revolution. Widespread flogging and repression in the ranks kept them from joining the swirling maelstrom….

The most dangerous disputes from the point of view of the authorities were the wage disputes and battles over mechanisation among the Spitalfields Silkweavers, and the work stoppage by the coal-heavers on the London docks. The silkweavers had been rebelling against wage cuts and increased use of machine looms for nearly a decade, but it was rising to fever pitch, with wage-cutting masters facing sabotage of their looms, intimidation of workers agreeing to low pay, and the formation of clubs of ‘cutters’ branching out into extortion of employers. It would climax the following year with gunfire and the army occupation of Spitalfields.

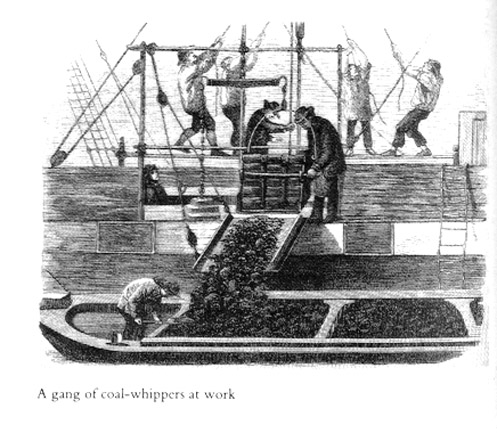

The coalheavers’ dispute was even more violent. As related in a previous post, for centuries one of the hardest jobs on the London docks was coalheaving: unloading coal from ships to warehouses from where it was sent off to fuel the City and industrial expansion. Coal lay at the heart of eighteenth century London life: not only was warmth, like food, basic to survival, but industry, business and commerce all needed coal to function.

Coal heaving, unloading coal from ships bringing it to London, was hard work, low paid, backbreaking; the heavers had a reputation for disorder and thieving, but faced harsh conditions which they were forced to combat in various ways. The work was centred on Wapping and Shadwell; Gangs of heavers were often controlled and organised by powerful City merchants and local publicans.

The heavers work patterns were being altered to speed up unloading of coal; ‘middlemen’, called undertakers, organised them into work-gangs, which worked to the interests of the coal-ship owners. But under the 1757 Coal Act, the coal heavers’ work was overseen by the aldermen magistrates of Billingsgate Ward, who registered the men, maintained a sickness and burial fund and regulated wages. By 1768 the magistracy was divided between a paternalist faction, interested in continuing protection of the workers (though with social peace and the maintenance of supply also at heart), and the representatives of the ship-owners, and large coal merchants… The latter were headed up by William Beckford, alderman of Billingsgate, largest sugar plantation owner (and thus slave-owner) in Jamaica. Beckford, ‘King of Jamaica’, twice Lord Mayor of London, MP for the City, was concerned to reduce the coalheavers independence to as near to the level of his Caribbean slaves as he could. Beckford is also where the links between the political and economic disturbances of 1768 come round full circle, since he was a stalwart supporters of Wilkes, a leader of the movement for reform in the City of London which saw sweeping changes to the corruption and inefficiency of the old regime as necessary for the unfettered growth of business interests and the pursuit of profit.

The confused mishmash of loyalties and interests here is typical of the time; perhaps some saw clearer than others, however, as striking sailors would by May 1768 sign a declaration ‘No W-. No K-‘ … No Wilkes, No King, breaking with the general support of the organised London workers for Wilkes… Why, isn’t certain: had they seen through the fundamental difference in interests?

Beckford backed the ‘undertakers’ who ran taverns in Wapping and Shadwell where heavers had to collect their wages and the gangs were also organised. “The tavern, even more than the parish, was the elemental unit of social life in London. The arduous nature of coal-heaving necessitated a close relationship with beer. The organisation of coal-heaving gangs, no less, required the public house. Since taverns were places of food and drink, control of them, especially during times of scarcity, was control of the river proletariat.”

The wage dispute erupted into open warfare, and the taverns were often the battlefield; heavers met in rival inns and mobbed the ones run by the gangmasters. Two ‘clerks’ (alderman’s aides), Metcalf and Green,hired by Beckford, ran taverns, organised the work, and drove down wages and conditions by hiring starving men from Ireland. The riverside was filled with Irish migrants (so many lived around one stretch of what is now Cable Street it was nicknamed ‘Knockfergus’)

But revolt against this evolved among the Irish workers, and the underground groupings of rural self-protection and resistance to British landlords in Ireland may have been used to build organised opposition on the docks. A wage dispute broke out and heavers stopped work. Scab labour was sent in from Green’s Roundabout Tavern (on Gravel Lane, now Garnet Street), and Metcalf’s Salutation Inn. In February 1768, the latter pub was gutted, and the war stepped up, as the undertakers allied with the constables and backed by Beckford pushed out the paternalist magistrate, Hodgson.

In April the Roundabout tavern was attacked by coalheavers with guns, fire was exchanged: “A shoemaker bled to death on the pavement; a coalheaver took a bullet in the head, ‘dropped down backwards, and never stirred more.’” This may be the same incident reported as taking place on April 15th in the Annual Register, but gunfire against scab taverns and those pubs where the striking heavers met was frequent for weeks. Green was charged with murder after these deaths, (seemingly the divisions within the magistracy were continuing), but he was acquitted.

The coalheavers were joined in May by sailors working the ships in the docks, agitating for higher wages, and ‘striking’ (lowering) the sails to prevent ship movement. The paralysis of work on the river became so overwhelming that ‘strike’ became general usage for refusing to work… and henceforth…

Further violence on board ships acting as scab labour in May brought mass repression, splitting the sailors and coalheavers; after a sailor was killed in battle on board a scab ship, several coal heavers were hanged, and the strikes were defeated… The army occupied the area to prevent further outbreaks, and ensure coal unloading carried on (two soldiers were murdered for unloading themselves).

In the end the massive agitation and riotous insurgency of 1768 peaked and declined, mostly in the face of massive state repression. The coalheavers continued to be unruly, if never again so effective. The Spitalfields silkweavers would also face vicious clamp-down after they became uncontrollable – but a few years later they would force the state to guarantee their wages, in a paternalist concession that would last 50 years. The class warfare against the changes in working conditions of course continued, though increasingly in other, less violent, forms.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2017 London Rebel History Calendar – check it out online.

Leave a comment