“The Commons have symbolic roots going back to before the Norman conquest. They stand for the right of every human to have access to the fruits of our earth: in stark contrast to the predatory individualism promoted by the ‘enlightened’ imperialist… This lack of feeling was a necessary precondition for a class of men who were destined to lead the conquest and exploitation of peoples and ecosystems across the globe…The spirit of the commons was the antithesis of this dominating cult of individualism and private ownership.” (Stefan Szczelkun).

“For though you and your Ancestors got your Propriety by murther and theft, and you keep it by the same power from us, that have an equal right to the Land with you, by the righteous Law of Creation, yet we shall have no occasion of quarrelling (as you do) about that disturbing devil, called Particular Propriety: For the Earth, with all her Fruits of Corn, Cattle, and such like, was made to be a common Store-house of Livelihood to all Mankinds, friend, and foe, without exception.” Gerrard Winstanley, ‘Declaration from the Poor oppressed People of England… to Lords of Manors’, 1649.

Open space in London has always been contested space. Many of the green spaces around London (and elsewhere) which remain today were preserved from being built on over previous centuries, by collective action – rioting, sabotage, occupation, as well as legal contests, campaigns, demonstrations… In the years before the 19th century, this was often about subsistence – access to the Commons and the resources available there, like wood for fires, food like fruit, nuts and small game, and grazing land, were crucial to many people’s daily survival.

By the late 19th century, with the massive expansion of London, crowded with millions living in often poor housing and working long hours, open space for pleasure and relaxation was at a premium, and fast disappearing.

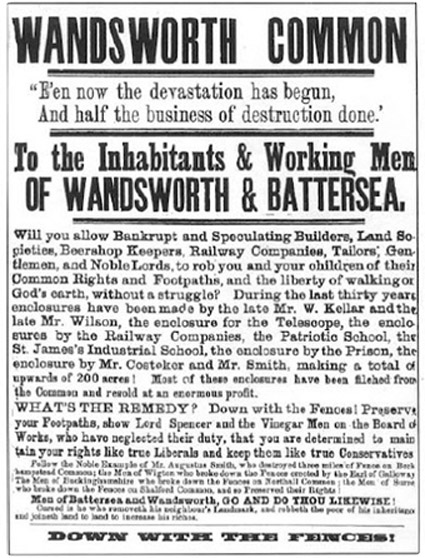

As part of our occasional series on enclosure battles around London, today we remember an incident in the resistance to the theft of Wandsworth Common.

Wandsworth Common is the remains of more extensive commonland which through earlier centuries had been known by a number of names, including Battersea West Heath and Wandsworth East Heath. It was originally part of the wastes of the Manor of Battersea and Wandsworth.

Between 1794 & 1866, 53 enclosures reduced its size; most of the enclosures were carried out by local bigwigs the Spencer family (later of Princess Di fame). Earl Spencer’s actions sparked protests in December 1827, when “a very numerous meeting of the most affluent and respectable gentry” of Battersea, Wandsworth and Clapham (held at the Swan in Stockwell) opposed an impending Inclosure Bill for the three respective Commons. They were partly concerned at threats to their own livelihoods, but also greatly worried that many poor folk would be deprived of a subsistence living – and thus become a burden on the rates! (Much was made of the results of the recent enclosure of Bexley and Bromley Commons, where ratepayers had ended up paying the price…) The Bill was defeated, but small scale enclosure continued.

The situation in Wandsworth was made worse by the Common being split into three parts by railway lines in the 1840s, & the enclosure of a further 60 acres for an asylum. At some point in the late 1840s, a Mr Parsons and others broke down fences aroun some enclosures, and were charged, but the case was dismissed, possibly on the grounds that they were asserting a traditional right of access.

Attempts by local people to preserve the Common against further encroachment began in earnest in 1868 when appeals were made to the Metropolitan Board of Works to take over responsibility, following the Metropolitan Commons Act of 1866, but this was initially unsuccessful.

The East Common was the centre of a fierce struggle in the 1860s. Mr Kellar, who owned land on the Common south of Bellevue road, claimed he had to enclose it to disperse ‘gypsies’ who had been camping there, who he accused of trashing the Common; but it later emerged that he had supplied the travellers with booze & then kicked up a fuss when they got pissed & had a rowdy party.

In 1869, 2000 people gathered to pull down enclosure fences on part of the Common, roughly where Chivalry Road is now, and the following year Henry Peek (who had played a part in the preservation of Wimbledon Common from development) called together a Common Defence Committee (later the Wandsworth Common Preservation Society) to save the land threatened with development by the Spencers. Large public meetings were held in Wandsworth, Putney and Battersea. The Committee fought an unsuccessful legal battle that April to preserve Plough Green (around modern Strathblaine Road and Vardens Road, off St Johns Hill).

The agitation to save Wandsworth Common, although led by wealthier residents, involved working class mass involvement, including mass meetings in local factories.

In parallel with the legal campaigning, some locals went in for a bit of direct action… On May 14th 1869, John Buckmamster, a leading light of the Common Defence Committee, was had up at Wandsworth Police Court, accused of “wilfully and maliciously destroying a fence enclosing the property of Mr Christopher Todd at Wandsworth Common.” Todd had bought the land from the railway Company, but campaigners claimed they had no right to sell, as the Lord of the Manor had no right to sell it to THEM. Breaking down the fence, Buckmaster stated that he was asserting common right. Public meetings on the Common (including one allegedly 5000-strong in January 1868) had passed resolutions to tear down Todd’s fences.

In the months following fund-raising efforts and lobbying of support accelerated. And so did the wanton destruction of property. On April 13th 1870, “a large number of persons assembled and asserted their right of way by breaking down the fences”. Some 300-400 people armed with hatchets and pickaxes re-established a footpath enclosed by a Mr Costeker at Plough Green, possibly opposite the Freemasons Tavern. A report later noted:“At each crashing of the fence there was a great hooting and hurrahing.” In June of the same year there were protests at Spencer’s plans to enclose part of Putney Common.

Eventually Earl Spencer agreed to transfer most of the common to the Defence Committee, excluding the area which later became Spencer Park. The rest was later saved for public access, and remains open to all today.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Centuries of hard fought battles saved many beloved places from disappearing, and campaigning led to the laws currently protecting parks, greens and commons. But times change… Pressures change. Space in London is profitable like never before. For housing mainly, but also there are sharks ever-present looking to exploit space for ‘leisure’. And with the current onslaught on public spending in the name of balancing the books (ie cutting as much as possible in the interests of the wealthy), public money spent on public space is severely threatened.

Many are the pressures on open green spaces – the costs of upkeep, cleaning, maintenance,

improvement, looking after facilities… Local councils, who mainly look after open space, are struggling. Some local authorities are proposing to make cuts of 50 or 60 % to budgets for parks. As a result, there are the beginnings of changes, developments that look few and far between now, but could be the thin end of the wedge.

So you have councils looking to renting green space to businesses, charities, selling off bits, shutting off parks or parts of them for festivals and corporate events six times a year… Large parts of Hyde Park and Finsbury Park are regularly fenced off for paying festivals already; this could increase. Small developments now, but maybe signs of things to come. Now is the time to be on guard, if we want to preserve our free access to the green places that matter to us.

Already space in the city is being handed to business – London’s Canary Wharf, the Olympic Park and the Broadgate development in the City are public places governed by the rules of the corporations that own them.

An example of public space being created, that will operate under private control, is the proposed Garden Bridge across the river Thames. Despite the promise of £60m of public money, if built under

current proposals, it will be plagued by corporate restrictions: cyclists would have to dismount to cross, while social gatherings, playing musical instruments, making a speech, releasing balloons and many other pursuits would be banned. It could be closed to public access for private events.

And increasing privatisation of space in cities is often tied up with CCTV, surveillance, control of our behaviour. Private space is space where they can tell us what we can and can’t do; space they can ban us from, keep us out of. Not that public bodies aren’t doing their bit: the last government introduced Public Space Protection Order (PSPO), allowing councils to make illegal ‘social problems’ like sleeping rough in an attempt to drive homeless people from town or city. Councils are also dealing with developers that give them control over paths. Planning laws are being ‘relaxed’ nationally to allow developers a freer and quicker ride when they want to build . Everywhere slivers of green not protected by law are vanishing; or social housing with access and views over green space is being replaced with new developments for the rich (as at Woodberry Down, or West Hendon). The threat to open space is part and parcel of the massive changes underway in the city, attempts to permanently alter the capital in favour of the wealthy, driving those who can’t afford it to the margins or out of the city entirely.

It may seem like parks, and other green spaces are givens; things that can’t be taken away. But what seem like certainties can be lost before we realise. Look at way social housing have been dismantled over the past 30 years. In the 1960s council housing was taken for granted as a right by millions: it has been reduced to a last resort, which current government proposals could sweep away. Or the way the NHS is being parcelled up into private providers… there are many who see green space as a luxury and something that can be got rid of or at least shunted off into the hands of some quango… Whatever gains we have, whatever we win, whatever rights we enjoy, came from long generations of battling – the moment we stop, rest on our laurels, powerful forces start pushing back against everything we have won.

If landowners, the rich, authority, have usually seen open space as a resource for their profit, or as a problem to be controlled, there has always been opposing views, and those willing to struggle to keep places open, and to use them for purposes at odds with the rich and powerful. From an invaluable source of fuel and food, to the playground for our pleasures; from refuge from the laws made by the rich, to the starting point of our social movements…

THE COMMONS ARE OURS!

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

More on enclosure battles in South London can be read in Down With the Fences (from which the section above on Wandsworth Common is an excerpt).

And some more of our ramblings on open space can be found in Stealing the Commons

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2017 London Rebel History Calendar – check it out online.

Leave a comment