The battle for Wimbledon Green

Following on from a previous post detailing the long and intricate campaign that preserved Wimbledon Common from enclosure in the 1860s… a reminder that not all campaigns to save open space from that era were successful.

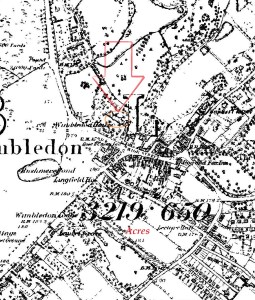

Wimbledon Green was a small piece of land, possibly roughly triangular, which stood next to, and may at some earlier point have become detached from, Wimbledon Common. In 1901-2 it became the focus of a plan to build on it, which faced vocal and violent local opposition. However, the campaign to keep the Green open and public ultimately failed.

Some of Wimbledon Green lay to the east of modern Parkside, stretching down to where the War Memorial now stands, where Parkside meets Wimbledon High Street – where a short road called ‘The Green’ remains as evidence.

Next to the Green stood Wimbledon House, an opulent mansion, in very extensive grounds stretching half way along Parkside. This had formerly been the residence of Joseph Marryat (father of the novelist Frederick Marryat), MP, banker and slave owner. After Marryat’s death his widow inherited the house, but on her death it was sold at auction to Sir Henry Peek, who bought as his town residence. Peek was a prime mover in the campaign to prevent the enclosure of the Common in the 1860s.

When Mrs Marryat died, the highest bidder at the auction had in fact come from a speculative builder who planned to demolish Wimbledon House and build several houses on the land. He paid a deposit, but then failed to complete.

When Mrs Marryat died, the highest bidder at the auction had in fact come from a speculative builder who planned to demolish Wimbledon House and build several houses on the land. He paid a deposit, but then failed to complete.

After some time Henry Peek, in fact did buy the house. After Peek died in 1898, aged 73, his heir decided to sell the house and land, and the ‘Wimbledon House Estate’ went on the market. The Common frontage had a depth of 170 feet and was valued at £35 per foot. It was bought by a company, again planning to develop the land.

The Green may have been small, but it was an important focus of local life. Wimbledon Fair had previously been held here, although this Fair was suppressed in 1840, at the insistence of Mrs Marryat, whose property lay next door; she asserted it “brought ruffians to the area” !

The Green also served as the local speakers corner; radicals, socialists & secularists held outdoor public meetings here, as did religious preachers and the local Temperance Society.(Another local speakers’ corner was the open space opposite the Crooked Billet & Old Town Hall, at the south end of the Common.)

was the open space opposite the Crooked Billet & Old Town Hall, at the south end of the Common.)

In 1901, the ‘Wimbledon House Estate Development Company’ announced plans to build on the land it had bought. It included in this most of Wimbledon Green. The whole of the land was fenced off.

Clearly to a certain extent, Wimbledon Green had a place in the hearts of some local people. Mrs Marryat’s reaction to the Fair showed that open land like this, used as it was for active and sometimes rowdy social and political activities, may have been viewed more dimly by other elements in the ‘community’(the more respectable ones). Possibly its use as a socialist gathering spot might have led some worthies to shrug their shoulders at the thought of it disappearing…

Immediately, arguments began about the possible loss of the open space on the Green. These centred around the Development Company’s claim to the land. Any title must have derived from the purchase from Peek and thence back to the Marryats.

Locals putting their faith in the powers of the Commons Conservators, who had taken over management of Wimbledon Common after 1871, were to have these hopes dashed. The Conservators met on Thursday 5th March, and quickly came to the conclusion that they had no legal jurisdiction over the Green, and thus no power of intervention. It had not been included in the land belonging to Lord Spencer at the time of the passing of the Commons Act of 1871.

Legally common land or not, many local folk felt an attachment to the Green, and expressed the relatively widespread view that the commons were theirs, from custom, from long use, from sentiment – whatever the law might say.

Only a few weeks after the Conservators meeting, alternative methods of preserving the Green were evident. Some form of protest rally or march was held to the Green, involving a crowd of 300-400 people; a bugle was blown as some kind of signal, and the 193 yards long fence was quickly torn down, smashed up and set on fire. A couple of gallons of paraffin seem to have been poured over it to make two blazing bonfires.

The eight policemen standing by were caught by surprise, it seems. They tried to extinguish the flames, but were only partially successful, so the “bevy of policemen” (as the newspaper put it) fell back, after taking the names and addresses of the perpetrators.

The incident took place at some point in late 1901.

Sabotage as part of a campaign against enclosure of common land, or what was felt to be common land, was not by any means unprecedented. Legal arguments and lobbying were often paralleled by the breaking down of fences.

The Wimbledon rioters could have taken inspiration from any number of campaigns to keep open space public; in London alone, fence-destruction had been employed as a tactic in the previous 30 years in struggles at Wandsworth Common, Wanstead Flats in 1871, Hackney Downs in 1875 , Plumstead Common and Chiselhurst Common in 1876, Leyton Marsh in 1892, and Eelbrook Common in 1878.

Arson was more unusual, though fences had been burned at West End Green in West Hampstead in 1882, and furze was burned during the riots against the enclosure of One Tree Hill by a golf club in 1897.

Although negotiations over One Tree Hill were dragging on when Wimbledon Green kicked off, numerous campaigns of fence breaking had been part of successful battles to preserve open space. The Wimbledon men had every reason to think it might also work there.

Although the Conservators clearly felt that Wimbledon Green was not part of the Common, as it had been quantified in 1871, this did not mean they were all indifferent to its possible obliteration.

Tyrrell Giles, Chairman of the Conservators of the Common since 1892 (and ex-MP for Wisbech) wrote to the Surrey Independent (apparently a Conservative newspaper) after the paper covered the fence-burning incident:

“Sir,

With respect to the statement published in the Daily Mail, and repeated, in your last

issue, permit me to say that the Board of Conservators have no communication of any sort with the Wimbledon Housing Estate Co., on the

subject, or it must have come to my knowledge as Chairman. That part of the Green is not coloured on the deposited map of the Commons and the Conservators consequently have no jurisdiction over it, but I venture to think that if they express an opinion at all, it would be unanimously against enclosure of a piece of the Green which to my knowledge, the inhabitants have had access to and enjoyed for over forty years. Personally I am prepared to assist in supporting the claim which we

have acquired by long use, that this small but important piece of Common should remain open and unenclosed.

Yours very truly,

C. Tyrrell Giles

Copse Hill House,

Wimbledon, April 9.”

The Wimbledon House Estate Development Company took out summonses. These were against twelve individuals whose names had been taken as assisting in removing the fence. The twelve appeared in March to answer the Summons, an adjournment was allowed to give them time to organise their defence, and they appeared again at the Wimbledon Petty Sessions. at the end of April.

The defendants were as follows:

Henry Brown, who lived in Winkfield Stables

Harry Carpenter of Durham Road

Horace Clarke of West Place

George Howsego – Newton Road

George Francis of Crooked Billet

George Shaw of Church Road

Charles Pain of Dundonald Road

Henry William Lovejoy, Balfour Road

Goorge Yates, High Street

Arthur Quick of Church Road

Henry Hawtin, Graham Road

John Merrit – South Place

One Thomas Jones was also named as a ringleader, but for some reason was never summonsed.

The men mostly lived very locally, very close to the Common and the Green, or had previously done so.

Meanwhile George Hawtin, another native born Wimbledonian, uncle of Henry Hawtin, one of the defendants, launched a Wimbledon Green Preservation Committee. Hawtin was a socialist who later became a founder of the Wimbledon, Merton and Morden Labour Party branch in 1918. At some point he was a bookseller in St Marks Place, Wimbledon Hill.

Most of the defendants were represented by W.H.Whitfield, a solicitor who lived and worked locally, but also had offices in Surrey Street, off the Strand. For some reason Henry Hawtin and Henry Brown were unrepresented or represented themselves.

The defendants appeared in court before a bench of magistrates including Thomas Arrowsmith Meates, who had been a founder member of the Wimbledon and Merton Radical Society in 1884, and Tyrell Giles, above-mentioned Chair of the Commons Conservators.

When the case came on, the prosecuting barrister objected to Tyrrell Giles sitting on the Bench, on the ground of bias – he had written to the press declaring decided views on the Green.

The case was to be dominated by arguments about the right of the Company to enclose the land in the first place – ie whether or not the actions of the demolishers were justified.

The fence, was said to have cost not £47 as previously alleged, but £30.12s 9d. The defence urged that those who had erected the fence had gone too far even if there was an honest claim of right.

They defence out forward three points to consider: –

1. That the land enclosed was a highway over every point.

2. That the land was a part of Wimbledon Common.

3. That it was the annual custom to have certain games and sports to the inhabitants

of the locus in quo and not equally exercised by non-inhabitants.

The Prosecution, maintained that the destruction of the fence was a wanton outrage, very expensive to the Company and that even if any common rights were being defenced, the sabotage was an excessive response.

Police gave evidence that Harry Carpenter had been “seen with a bottle” (possibly the accelerant?). PC Walsh 487V had spoken to the throng when the fire was alight, and when the crowd rolled the fence in the direction of the fire he was obliged to get out of the way. He thought that Hawtin and Thomas Jones were the ringleaders.

Constable Hill said the crows was very good humoured. At some point Horace Clarke was discharged.

The defence brought witnesses to testify that the Green was common land, a popular tactic in such cases, where long memories of the area’s oldest residents was often held up as proof of the customary use of the land.

Joshua Joyce Caswell, then aged 73, of Croylands, Southside, (who had been Chairman of the Local Board in 1896-7,) testified he could remember the Green being open and unenclosed all his lifetime. He had played cricket on it when a lad, and had seen it used for games, beating carpets, and as a rendezvous for the assembly of the volunteers. Not only that, but the parish had used the land – building a public pound upon it, in which the horses of gipsies who used to assemble upon the common were impounded, using the water of a well on the Green to wash down the High Street, and repairing a bench there. Casswell remembered that after the late Sir Henry Peek came to Wimbledon, two elm trees were cut down on the Green and removed by the agent for the Lord of the manor, and so far as he was aware, Peek made no complaint about this – suggesting Peek at least has not claimed to own the land and considered it part of the manorial holdings.

Mrs Drax, who owned property in Wimbledon, still claimed a right to graze cattle upon the Common, and Casswell had recently seen some cattle belonging to Mr Jay who rented Mrs Drax’s land, grazing on the Green. There was also a track going across the Green which had always been used as a short cut for children going to school.

Cross-examined, Casswell was asked if he was aware that a notice board had been affixed to one of the trees claiming that the land belonged to Sir Henry Peek. He said he was aware of that, but that Peek had planted trees and put a seat on other parts of the common near Caesar’s Well, which he had repaired and put his name upon, but this did not make it his property.

Casswell said he had not been present at the pulling down of the fence, claiming he did not know it was in the offing, or he would surely have been there himself!

The magistrates deliberated, and came to the conclusion that they did not think the Company had made out a sufficiently strong case that they did on fact own the land, to support their summonses. “The Chairman pointed out that the whole point of the case was that the defendants had destroyed the property of the Company. But it was very doubtful whether the fence was their property for having put it on the ground it became vested in the lawful owner of the soil and there was no evidence that the Company was the lawful owner.”

The case against the defendants was dismissed, with £5 costs and a court fee of 18 shillings. Upon leaving the Court the twelve were cheered and carried shoulder high by a supportive crowd.

But although the saboteurs seemed to have got away with it, the land remained in the possession of the Development Company, and the fence was rebuilt. The Company dug a huge pit on the land, which was now guarded by three constables, day and night to prevent any further attacks on the fence.

Attempts to resolve the issue and re-open the land continued. The ‘Committee for the Protection of Wimbledon Interests’, a small group of mainly well-to do local citizens, held negotiations with the Estate Company. The Committee submitted that if a claim to the Green could be established that over-rode the Development Company’s claim, they expected that terms would we arranged, and the plot transferred to the Commons Conservators, or to Wimbledon District Council (then the local authority).

Whether the Development Company even contemplated settling is unclear, but unlikely.

In any case they continued to take action against the saboteurs; acting through the Solicitors Messrs Home and Birkett, they issued writs in the Court of Chancery against the twelve defendants who had recently been summoned before the local Bench of magistrates. None of the defendants could afford to defend an action in the High Court, so none put in an appearance, and judgment went by default to the Company.

On 17th July 1902 indignant local citizens gathered to hold another protest meeting about the theft of the Green, beginning in the Broadway and ending with a march on the Common. There was such a heavy police presence that the events of the previous year were not repeated.

In the same month, the Wimbledon Green Preservation Committee sent a deputation to the District Council, consisting of eight people: Tyrrell Giles, who acted as spokesman, J.J.Casswell, who had given evidence at the hearing against the twelve fence-burners; James Friggs 4 of 26 Alexandra Road, a fairly well-known as a local radical; Richardson Evans, “now chiefly recalled as originator of the John Evelyn or Wimbledon Society”; F.Satchwell, an engineer; F.Brown; J. Grose, an active and vociferous immigrant (possibly refugee?) socialist, and George Hawtin, still the Honorary Secretary.

However, the District Council had taken legal opinion; A.McMorren KC had advised them that the fact that the title went back at least to Peek supposedly owning the land in 1875 gave the estate company a degree of title, how good he would not say, but at any rate a degree of title.

However, the town itself had no title whatsoever, and they could not take the company to court without a title themselves.

McMorren felt it could be proved that at least part of the Green had belonged to the waste of the manor, and so if a commoner with any rights could be found, the Council could ask them to put themselves forward to at least nominally take a legal case over the enclosure. Noone who had any demonstrable common rights regarding the Green could either be found or was willing to step forward, however.

McMorren was asked if the public had any right of way, as the Council was bound to defend a right of way, but McMorren thought there was none.

Sensing they had no real legal case, the District Council decided to drop the issue in July or August 1902. Dr.Barton, a resident in Lingfield Road, argued that the Council should move to negotiate for the purchase of the land, and he was seconded by J.M.Boustead. But they were the only two who voted for it. The motion was lost 13: 2.

In June, 1903, it was reported that a long discussion had taken place among the

Commons Conservators as to ‘whether they should apply for a conveyance of the waste land lately leased to the Company for building purposes but it was

decided that the matter was not of sufficient importance to the general body of those paying the common rates to warrant the risk of incurring an action at law and that nothing further should be done’.

J.J. Casswell was still up in arms, if only verbally. When in November, 1903, the Surrey Independent got hold of a rumour that he was going to be made a JP the paper quoted him as saying that “If he could have his desire he would authorise the dragging of the advisers of the Wimbledon House Estate Co. through the pond “which, according to his contentions, they had dug without the least legal right.”

Wimbledon District Council may have dropped any legal plans, but was still discussing the issue in the middle of 1904. The area under consideration had not , yet, been built upon, so they may have thought there was still room for an agreement to be reached.

The council wanted to negotiate with Lord Spencer, the lord of the manor (it’s unclear as to what they thought this might achieve).

Meanwhile the Commons Conservators arranged for three prominent local residents to meet with a representative of the Development Company. Sir T.G.Jackson, a distinguished architect, Walter Dowson, a well-known local solicitor, a politically active Conservative, and Richardson Evans (who had formed part of the Preservation Committee delegation to the Council two years earlier), met a representative of the Property Company, Mr. Minter. This meeting took place in “a yery friendly spirit”, and they discussed whether the Conservators could lease the land in question, for £100 a year, for a term of 99 years, with an option to purchase.

But nothing came of any of this proposal. The whole issue seems to have fizzled out.

Conclusion

The struggle at Wimbledon Green stands out among battles to preserve open space in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in London area, in that where most such struggles were successful, here, it was not. It is difficult to definitively say why. The combination of a rowdy element prepared to commit illegal acts of sabotage and arson and a host of local worthies and notables prepared to campaign respectably was one that had proved a winner in many other areas.

Perhaps in the end it was to do with there being no one person prepared to push the case legally to the end (and having the funds to do so), or more broadly a lack of will at the District Council.

Clearly although the Green was valued locally and was felt to be customarily part of common lands, legally it was not so. But this was the case at One Tree Hill, never itself common land, but where enclosure was successful challenged despite there being clear legal title by the enclosing landowner. The sheer weight of numbers involved in the One Tree Hill riots (thousands rather than hundreds) suggests maybe that it came down to Wimbledon being a more affluent area, further from working class districts from where large crowds could be gathered.

@ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @

This post is entirely derived from the excellent research of Gillian Hawtin, and her pamphlet ‘The Battle for Wimbledon Green’, published in …..

Gillian’s father George and cousin Henry had been involved in the campaign to preserve the Green.

Leave a comment