Squatted army camps in South Buckinghamshire

After the Second World War, homelessness, a shortage of homes due to bomb damage, millions of ex-servicemen suddenly returning from the war, and chronic overcrowding sparked a nationwide movement of squatting. In 1946 there was an outbreak of squatting in Wycombe (a Municipal Borough) and Amersham (a Rural District) in South Buckinghamshire. There was extensive squatting in South Buckinghamshire, as across the country as in many other areas, mainly in army camps that had been left empty by post-war demobilisation.

The first camp to be squatted in South Buckinghamshire was the Vache in Chalfont St Giles [Incidentally the big house here was once home to George Fleetwood (1623–1672), a major-general and one of the regicides of King Charles. In 1660 George Fleetwood was found guilty of killing the king, and although his life was spared, his estate of The Vache was confiscated and given to the then Duke of York, the future King James II]

Former commandos believed that 500 Polish soldiers and their Italian brides were being sent to live there. The Army denied the story, and the ´Italian brides´ turned out to be Polish women who had married soldiers of General Władysław Anders Polish army in exile while it was fighting in Italy.

One of the first of these occurred at The Vache in September 1946. The leader was an ex-Commando, John Mann, of Chalfont St. Giles, who had been sharing a small cottage with his wife, his five-year-old son, and ten strangers. At the local pub one night, Mann heard a Polish captain say that a deserted army camp at nearby Vache Park was being readied for Polish soldiers. Mann decided to get there first. At dawn, he and a handful of homeless veterans bloodlessly routed three Polish guards and seized Vache Park. Next day, 120 families had moved into the spacious army huts. After a flurry of resistance, local authorities capitulated.

Also squatted in this part of the county were the badly-vandalised former Italian POW camp in Chairborough Road, High Wycombe, and the biggest camp in the area, at Daws Hill, High Wycombe, with 220 Nissen huts, squatted by an initiative of Labour party members and Communists, with the support of Charlie Lance, polıtically ‘independent’ Mayor of the Borough.

Other camps squatted were at Beech Barn at Chesham Bois, Pipers Wood in Amersham and at Hazlemere, near High Wycombe. at Beech Farms, Chesham Bois, Polish soldiers raced squatters to grab empty huts, staked their claims by installing beds. When they returned with the rest of their belongings, the beds were on the lawn, the squatters in the huts. Demobilised soldiers from Gen. Anders´s army also lived at several other similar local camps. At first, hostility to the Poles was widespread. It was encouraged by the Communists, who wanted ‘Beech Barn for the British’, and a local residents’ association that wanted the Poles housed on Salisbury Plain or in Cornwall.

There was also squatting a few miles to the south, at Chandler’s Hill Camp, Iver: soldiers sent S.O.S. calls to the police when the squatters moved in, (the cops never turned up!) but the squaddies wound up amicably sharing the camp with them.

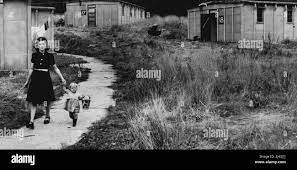

Life at the camps was very hard at first. The huts had roofs of double-sheeted corrugated iron, and they were cold and damp. There were separate ablution blocks with shared bathing and toilet facilities. The locations of the camps were often inconvenient, and getting fuel was often a matter of spending afternoons pushing a pram filled with coke. At Daws Hill, telegraph poles were cut down and used for fuel. Later, money (gifted directly from central government) was spent to improve the huts, sealing the roofs with bitumen, plumbing in individual baths and toilets, and dividing the huts into separate rooms. Amersham Council had £33,336 from the national Exchequer for camp improvements in 14 months in 1949-50, at a time when the cost of building a new permanent council house was around £1,200. The plumbing work in particular made the huts much more attractive. There were 4,000 houses without bathrooms in High Wycombe, and the council opened new slipper baths for residents of these dwellings in 1947.

The squatters were not just people who had grown tired of waiting for new houses. Many were people who had never had houses before. Said Squatter Violet Bree at Vache Park: “Is it not wonderful? So much space! We used to live in one room with my mother-in-law—I was terrified of her. They say it will be ten years before we get a house, but I do not mind if we can stay here. There is another room behind there (they are going to knock a door through) with a telephone. I never had a telephone before.”

Squatters at the Vache paid Leader John Mann seven-and-six a week to build up funds in case of eviction.

The squatters organised to improve their living conditions. The Communist Party was active at Daws Hill, with Ron Williams’s November 1946 election campaign as ‘Building worker, Squatter, Communist’. In the early 1950s, three of the Daws Hill squatters became Labour borough councillors, and they promoted the building of more council houses in Wycombe. In 1949, when the Cold War was already changing attitudes, the Communist party was active in Amersham, recruiting members at Beech Barn over a demand for gas cookers. A campaign with the support of Phil Piratin MP compelled the council to take over Pipers Wood camp, and to make improvements there, and also in 1949 the CP had a Rural District Council election campaign.

Amersham council struggled with difficulty to tame the squatters. At first the squatters themselves controlled allocations. Once when the squatters went looking for some locals they wanted to allocate a hut to, a couple who had gone to see a film, the cinema agreed to show an appropriate message on the screen. When huts were set to demolished, new squatters moved in ‘due to a lack of despatch’ by the contractors. When it took new squatters to court, Amersham council was unsuccessful, and indeed was publicly humiliated, as the judge demanded to know why the council was not helping these people, instead of evicting them? As late as 1956, Amersham had difficulty in getting evictions for squatters who had not paid the rent.

The camps were young communities, posing an alternative to the multi-generational households of the day. ´You could have right good row – it was heaven on earth´, as one squatter remembers. The squatters were people who were perhaps a little more adventurous than the norm. The South Bucks squatters included single parents, divorcees, those who had remarried in wartime, and a Hoovers shop steward who was living with a woman factory supervisor described as ‘promiscuous’. There was also a woman who came to the area on a post-demobilisation holiday and decided to stay. These were people who had responded to the opportunities of wartime. Councils often complained that squatters came from out of the area, but the Daws Hill squatters ‘came from the town, perhaps not many were from Wycombe originally, but they had been in the town during the war’. Relations between the Poles and the squatters became more amicable over time, and one of my informants married a Polish soldier at her camp. These estates were closely-knit communities, and in this respect they were perhaps more like present-day sheltered housing schemes than general needs housing. At times there was a holiday camp atmosphere, and there were even moral welfare investigations of the squatters, but no proof of immorality could be found.

The squatters stayed on the camps until the mid-1950s. Hutted camps made a significant contribution to local housing, and by March 1950, Amersham RDC had 666 prewar and 333 postwar council houses, 90 prefabricated houses, 52 requisitioned properties, and 335 tenancies on seven hutted camps, making a total of 1,496 dwellings. All the original squatted camps had closed by 1956, with the residents rehoused, although some Polish camps remained open a few years longer. One, Ernest Barnett said, ´I´ve never been ashamed of being a squatter, I´ve often been proud of it. At least we made something for ourselves, and didn´t rely on other people´. Most of the squatters became tenants of council houses and flats, at a time when council housing was a tenure of choice for working class people, so squatting worked well for them.

The squatters were relatively few in number, and came from what might have been a somewhat marginal and not very respectable layer of the population, but they remained connected to the rest of the working class, and to the decision-makers in society. Their ideas may have embraced self-help, community and patriotism, class feeling, and a determination that the promises of war time should be delivered upon. Squatting worked to promote council housing nationally, by the fear it instilled at the top of society, by the agitation of the Communist party, and by the important intermediate role played by the ex-squatter Labour Councillors like Wally Wright, Harry Slight and George Fairbairn. The fact that they had had to squat after the war was part of these Councillors’ political narrative, that served to legitimise their policies in later years. Similarly, a layer of new members joined the Communist party out of the squatting.

The experience of the post-war squatters helps to inform arguments about the extent and limitations of the radicalism of 1945. It has been argued that there was little socialist content or working class militancy attached to Labour’s election victory. Strike figures in 1945-51 remained low, as the right-wing union leaders held the line in support of Attlee. In this context squatting, with its strange new mood of orderly lawlessness, reminds us that there was indeed a volatile social force acting from below, as working people demanded a better world in this period. Squatters both in camps and in the central London luxury flats had a lot of support in public opinion.

There is some film footage of squatters in the Chalfont St Giles camp here

https://youtu.be/SHW8G1Y4zKM

PS: The Vache is also the site of a monument to Captain James Cook, erected by Admiral Sir Hugh Palliser. Which I have visited and it is very bizarre… his role as an enabler of British colonialism and the violence associated with his contacts with indigenous peoples is glossed over… Sadly Cook was killed while trying to kidnap a Hawaiian chief by islanders who saw him for the coloniser he was…

Leave a comment