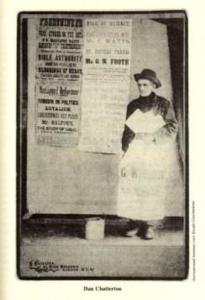

DAN CHATTERTON: ATHEISTIC, COMMUNISTIC SCORCHER 1820-1895

‘Who does not remember, in the stormy days of ’87, a pale, haggard old man, who used to climb the platform at meetings of the unemployed, or in the closely packed Socialist lecture halls, and pour forth wild denunciations of the robbery and injustice that flourishes in our rotten society, mingled with fearful prophecies of the terrible revolution that was coming. He looked as he stood in the glare of the gaslight, with his ghastly face and flashing eyes, clad in an old grey overcoat and black slouched hat, a red woollen scarf knotted round his neck, like some grim spectre evolved from the misery and crime of the London slums, and middle-class men who had entered the meeting from curiosity shuddered as they murmured to themselves “Marat”.

‘Yes, Marat come to life again, an English Marat.’

(From anarchist David Nicoll’s obituary of Dan Chatterton)

In his history of British Anarchism, The Slow Burning Fuse (Paladin, London, 1978) John Quail wrote of Dan Chatterton that he deserves to be rescued from oblivion. In a period, the late 19th century, when remarkable people were common among both secularists and socialists, Chatterton was one of the most remarkable of all, a one man revolution against church and state.

This post is nicked largely from an article by Terry Liddle, and/or Andrew Whitehead’s research into Chatterton.

Chatterton was born in August 1820 into an artisan family of fairly comfortable means in Clerkenwell in London. His mother was a Christian but Chatterton was early influenced by his father who worked as a furniture laquerer and who took the young lad to radical and freethought meetings at Richard Carlile’s Rotunda in Blackfriars Road.

Clerkenwell in south Islington was, until the last years of the nineteenth century, largely given over to small workshop trades – particularly watchmaking in all its branches, but also the jewellery and precious metal trades, brass working, bookbinding and book-edge gilding, specialist printing and fancy cabinet making. This engendered a tradition of artisan radicalism in Clerkewell which endured from the late eighteenth century through to the emergence of the Social Democratic Federation. as a popular political force in the mid-1880s.(Whitehead)

[See also Reds on the Green]

From an early age Chatterton suffered ill health and was sent away to be educated in Aylesbury and later Barnet. His father suffered an accident and changed his work from japaning to selling coal. Chatterton was apprenticed to a shoemaker in whose workshop he had his political education. Shoemakers were then in the vanguard of working class politics. Without success Chatterton tried to start his own business. By 1871 he was listed as a travelling bookseller and later as a newsvendor. In later years he made a slim living selling radical papers and posting bills. He claimed to have been a waiter in a coffee house and a baker’s deliverer and even to have cut up a corpse for a doctor.

a shoemaker in whose workshop he had his political education. Shoemakers were then in the vanguard of working class politics. Without success Chatterton tried to start his own business. By 1871 he was listed as a travelling bookseller and later as a newsvendor. In later years he made a slim living selling radical papers and posting bills. He claimed to have been a waiter in a coffee house and a baker’s deliverer and even to have cut up a corpse for a doctor.

Chatterton became involved in Chartism and claimed to have been badly injured in fighting between Chartists and police on Clerkenwell Green. In 1855 Chatterton joined the army, doubtless like Bradlaugh for the bounty:

“The main inducement, it must be supposed, was the seven pounds bounty. It was a curious step for an ex-Chartist to take, which which he did not seek to explain in later life, in spite of his vigorous denunciations of military ventures overseas. He was not well-suited to military life, being frail of build and just over five feet four inches tall. It’s hardly surprising that Chatterton seems to have spent much of his miliary career in a hospital bed in Malta. He was discharged after two years in the army.” (Whitehead)

Returning to London, Chatterton married Emma Cook, who died aged 32 in St Pancras Workhouse. He married again in 1867 to Emily Scott aged 21. Her fate is unknown; she was not living with Chatterton in his later life. Several children died young. Only one, Alfred, reached adulthood. He was disabled and lived with Chatterton. His circumstances undoubtedly put a sharp edge on his politics.

In the 1860s Chatterton was active in the Reform League participating in the Hyde Park riot of July 23, 1866. In the early 1870s he was a leading figure in the Land and Labour League. He wrote for its paper the Republican and spoke at its meetings. Unlike many League members he was not influenced by the Chartism of Bronterre O’Brien. Nor was he a member of the First International. He was, however, involved with the Universal Republican League.

The National Reformer for 26 May, 1872 reported a Universal Republican League meeting in Camberwell where ‘citizen Chatterton’ spoke on land and money lords. It is not recorded if he spoke at Church Street in the morning or at the Rose and Crown in the afternoon [both were then regular street speaking pitches for secularists and republicans in Camberwell]. Either way the land and money lords would be in for a good tongue lashing. Chatterton always admonished the poor to revolt against their oppressors and was always saddened when they didn’t.

Chatterton was also in the Patriotic Society, a radical debating club, which having been evicted from the Hole in the Wall near Hatton Garden [“…when the notoriety of that society prompted the police to persuade the publican to deny hospitality to `red republicans’ “] purchased what became the Patriotic Club in Clerkenwell Green (now Marx House).

“One well-informed contemporary, looking back on the ‘Hole-in-the-Wall’ days, recalled that the ordinary run of debates was decidedly disappointing: Every tone, every aspect, every sentiment impressed upon you the fact , that this was no gathering of tribunes, but a homely meeting of ordinary British artisans, with little more than the average brain and knowledge of their order. The rant of rebellion was rarely in their mouths, which spoke rather the more sincere, if more prosaic, discontent of the toiler who finds times hard and the hearts of the rulers harder. (Whitehead)

But occasionally, the author went on, some daring discourse was indulged in and the Communist Chatterton was the sincere and simple type of reformer that looks from the meanness and misery about him –

And sees aloft the red right arm

Redress the eternal scales.”

Chatterton also served on the general committee of the Anti Game Law League, “which held that the existing Game Laws `by creating a legal offence which is no sin . . . form a manufactory for the product criminals’.”

“He had also, by his own account, been active in the National Education League, but found there very limited support for his stand in favour of not simply non-sectarian education but exclusively secular instruction.”

(Whitehead)

Pamphleteering

Chatterton’s first pamphlet (1872) was in support of Metropolitan police officers who were agitating for a pay rise.  It became a diatribe against all social and political privilege. Chatterton argued that once the police and army started to think for themselves they would join a popular revolt.:

It became a diatribe against all social and political privilege. Chatterton argued that once the police and army started to think for themselves they would join a popular revolt.:

“in fact, an entire smashing-up of kings, queens, princes, priest and policemen, land and money mongers, and rascality of all sizes and degrees – in a word, an entire re-organisation of Society, on the basis of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity … The only police force you might require would be a small force to arrange your street traffic. Prigs, paupers, and prostitutes, legalised and otherwise, would gradually vanish into the ranks of Labour.“ (Whitehead)

For the next twenty years there followed a stream of pamphlets, increasingly intemperate in language and wild in appearance. All were militantly atheistic and denounced the evils created by gin and gospel. The royal family and capitalist politicians were favourite targets. Victoria, he said, should become a washerwoman and Gladstone a bus conductor.

In an 1882 open letter to the Prince of Wales, Chatterton wrote: “… the revolution of the belly without brains, a revolution that will sweep you, Prince, and the entire gang of royal lurchers into the ranks of labour or off the face of the earth, like the vermin you are.” The Windsors don’t have such critics nowadays.

The Commune In England

The nearest he came to a political programme was in his pamphlet The Commune in England. Everyone over 20 would elect a senate to draft laws to be submitted within a month to referendum. These laws would have included free secular state education and nationalisation of land.

Chatterton was an active freethinker and had an exchange of letters with the Archbishop of Canterbury which was published in The Times. Amongst the publications he hawked were the Freethinker and the National Reformer.

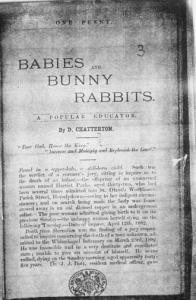

He was also involved in advocating women’s rights and family limitation in his pamphlet Babies and Bunny Rabbits. He was an active worker for the Malthusian League:

“Long residence in the slums around Kings Cross and in Covent Garden gave Chatterton first-hand knowledge of the severe housing problems facing the poor. In 1871 Chatterton and his wife were among four families and sixteen people living in a house in Cromer Street. The building in Cross Lane, where Chatterton and his son were living 10 years later, was even more crowded, with eleven families and a total of thirty residents. He once gave vent `in a vehement and unreportable manner to the condition of the poor, remarking that he lived in a house in which every brick was loose, and yet the rental of it was £l26 per year (shame), and not fit for a pig to live in.[26] He was damning about the official reports and inquiries into working class housing, insisting they were all `in the swim’. He submitted one of his pamphlets to the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes, and was scathing about the Commission’s insistence on taking evidence from local dignitaries – `these wealthy rascals never can know anything of the inner life of the poverty stricken dwellers in our Slums’ – rather than from the poor themselves.

Chatterton is notable also for his championing of women’s causes. He frequently referred to the thousands forced by poverty into prostitution, and consciously used the phrase `women and men’. Chatterton went out of his way to emphasise that women as well as men should work to destroy the social order and would benefit from the classless society he envisaged. His advocacy of contraception was based on the neo-Malthusian ground that smaller families would alleviate poverty, but there was also a hedonistic strand, absent in much other pioneering birth control literature, emphasising the enjoyment of sex. In 1883, a few years after the trial of Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant for republishing the Knowlton pamphlet on birth control, Chatterton outlined his views on family limitation in a penny pamphlet entitled Babies and Bunny Rabbits: a popular educator:

“Mothers of England, think well over this question – know that you are the framework of the evolutionary propagation of the forces of life; know that the means of restricting that propagation lies entirely in your own hands; feel that you may gratify, to your heart’s desire, all the sexual pleasures of love, of life, of all desire, without having the bitter reflection that by your reckless act of reproduction of a greater number than your two selves, you have doomed all to the penalty of death by starvation.”

The pamphlet went on to refer to the withdrawal method, and the use of the sheath, and gave the address of a supplier of a vaginal syringe recommended by Annie Besant.

Although what has been described as the ‘social conservatism’ of the Malthusianism League, and its reticence in addressing itself to the means of birth control rather than simply establishing the need for it, fitted uneasily with Chatterton’s style and motivation, he was an active worker for the League. Chatterton described the population question as the most urgent facing the poor, and at the Malthusian League’s annual meeting of 1884 explained the very personal reasons for his commitment to the cause:

question as the most urgent facing the poor, and at the Malthusian League’s annual meeting of 1884 explained the very personal reasons for his commitment to the cause:

He lived in one of the vilest slums of Drury Lane, and consorted with people who had nothing but a pauper’s grave staring them in the face. Thousands and thousands of poor people in London had no bed to lie on. He was a Communist, and more than that a strong Neo-Malthusian. He advised the poor to marry if they pleased, but to have as few children as possible until they were better off. He himself had drunk deep of the cup of human misery, having been the father of ten children, eight of whom were dead, and having witnessed sights enough to drive him into despair. He strongly urged the claims of the League on the attention of the poor and suffering. Without small families there was no chance for them. Delicate children he held should not be allowed to live. (This statement was met with marks of vigorous dissent from the audience). The cause of war was indigence, for the ill-fed and hungry took the shilling and fought in the Soudan and other climes against poor innocent people to please a set of greedy capitalists.” (Whitehead)

Chatterton’s Commune

Around 1885 he established his own regular penny publication, Chatterton’s Commune: An Atheistic Communistic Scorcher

The first issue appeared in September 1884, and it came out quarterly until April 1895, just a few months before Chatterton’s death. The early issues were cyclostyled, but the Scorcher soon established its regular four- or eight-page format, printed rather haphazardly in jumbled type on coarse paper, or more frequently on insubstantial yellow tissue. Chatterton was the sole contributor, the compositor, the printer and the vendor. He had no proper press, and so achieved an impression by rubbing with his fingers on a small block of wood. That necessarily restricted the print run (if that’s the right term) to about 100. As Chatterton’s health and eyesight declined so `Old Chat’, as he styled himself, became more determined to keep the Scorcher going:

“We Are Too Hot for Hell. Too Mad for Hanwell. The Scorcher not Go Broke. A Quire of Yellow Tissue, Sixpence  and A halfpenny-worth of Ink. Pull that Lot. Repeat Quantum. Pull again. And untill Issue of paper is Out. To do this means Stern determination, In long hours Night after Night, Very little gain But No Loss. Expenditure Two Pounds – per Year. Income, Three Pounds. Now Isn’t I A Scorcher? I am Seventy Years of Age, – Going for that other Fifty, deaf and near blind. Yet never daunted, Bring me my Compeer. But Remember What I can do, So can You (Go and Do It). Then Our World – will be A Scorcher Too.”

and A halfpenny-worth of Ink. Pull that Lot. Repeat Quantum. Pull again. And untill Issue of paper is Out. To do this means Stern determination, In long hours Night after Night, Very little gain But No Loss. Expenditure Two Pounds – per Year. Income, Three Pounds. Now Isn’t I A Scorcher? I am Seventy Years of Age, – Going for that other Fifty, deaf and near blind. Yet never daunted, Bring me my Compeer. But Remember What I can do, So can You (Go and Do It). Then Our World – will be A Scorcher Too.”

Chatterton was a powerful orator although many of his interventions were not well received. At a meeting organised by the Clerkenwell Branch of the Social Democratic Federation he threatened to decapitate the guest speaker Lord Brabazon.

“… and old Chatterton who, for all his diatribes against the aristocracy had never got a chance of giving one of its members `a bit of his mind’, was naturally on hand. The noble philanthropist had just been round the world and was full of emigration as a panacea for the congested poverty of the old country. He discoursed on the subject for an hour, to the amusement of an audience of which no member could have raised the price of a railway ticket to Clacton-on-Sea, much less the fare to Canada.

Then Chatterton struggled on to the platform and poured out his indignation. Gaunt, ragged, unshaven, almost blind he stood, the embodiment of helpless, furious poverty, and shaking his palsied fist in Brabazon’s face, denounced him and his efforts to plaster over social sores, winding up with a lurid imaginative account of the Uprising of the People and a procession in which the prominent feature would be the head of the noble lecturer on a pike. I shall never forget Lady Brabazon’s face while this harangue was delivered.“

(H.H. Champion, the organiser of the meeting, who had invited Lord Brabazon: able to take a more relaxed view of the incident in later years…)

At a meeting at the Autonomie Club in 1890 the description by William Morris of the beauties of a socialist society had no effect on him. He merely remarked that hanging was necessary for the public good. EP Thompson deleted any mention of Chatterton from later editions of his biography of Morris.

Chatterton drifted towards the newly formed anarchist groups. He sold anarchist magazine Freedom and spoke from the platform at a meeting to celebrate the Paris Commune and from the floor at a meeting addressed by Peter Kropotkin.

In the closing years of his life, Chatterton lived in the notorious slums off Drury Lane. One of Charles Booth’s investigators, a City Missionary, visited rooms recently vacated by Chatterton at 12 Parker Street:

“On the second floor there were till lately a father and son, bill posters, of good character. The man is a notorious Atheist, one who holds forth on behalf of his creed under railway arches, saying that if there be a God he must be a monster to permit such misery as exists. This man suffers from heart disease, and the doctor tells him that some day in his excitement he will drop down dead.”

Chatterton lasted another six years in his new lodgings, a room in a model block on the corner of Goldsmith Street and Drury Lane.

According to the death certificate, Chatterton succumbed to pneumonia and asthma on 7 July 1895, within a few weeks of his 75th birthday.

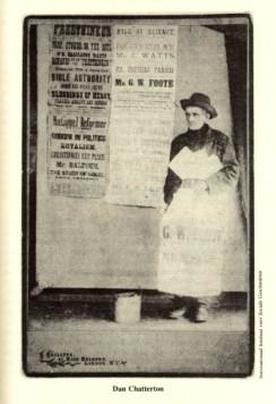

In a pamphlet [the last he published] Chatterton had written: ‘Oh if there be a hell and the atheists are damned and double damned, at least give me warm quarters and respectable companions.’ Chatterton wanted to be cremated. To fund this he sold photographs of himself at a shilling (5p) each. Alas he was to be disappointed. He was buried in a common grave in St Pancras cemetary in Finchley. The funeral ceremony was conducted by Robert Forder, a prominent secularist and radical publisher. Forder himself would be buried in a common grave.

Much of what we know of Chatterton today is because of his habit of placing his writings in the British Museum. He was an eccentric but he was the sort of eccentric that secularism and socialism need. Without extremists like Chatterton there is a danger we will fall into the trap of wanting to offend nobody, even those who roundly deserve to be offended.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Dan Chatterton’s Autobiography

Written a few years before he died, Chatterton describes his time as a lifelong London working class radical and revolutionist.

The original printing of the Biography is reproduced here

The subject of this Biography is one of the revolutionary type of workers for political and social advancement. Daniel Chatterton was born at Dorrington Street, Clerkenwell(1), London, August 25th 1820. His parents in a fair position(2), the eldest of three children – a lad of weakly constitution he was much petted by Father – and Mother, who spared no effort to preserve his life. His earliest recollections are the kindly care of a worthy couple at boarding school at Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire where his father placed him to get pure air. After three years spent very pleasantly, he came to London, when his mother an earnest Christian woman tried hard to inculcate a belief in the teachings of Christianity. But Young Chatterton’s Father, an Atheist, placed the contra side before his mental vision, telling him to hear both sides – he need not take the teachings of either as an accepted fact – but test everything by reason. His brain power. Today he reveres the memory of both. Yet he hails the effort that has preserved him from the enthrallment of that teaching which has worked such disastrous effects on the human race. His health again failing him he was sent to school at Barnet, where he remained until an accident deprived his father of his reason.

Brought home, Chatterton commenced active life at twelve years of age – before he was fourteen he was  apprenticed to a Bootmaker. And now mixing with workmen who are proverbially thinkers, he gained much useful information – entering into business before he was twenty one he was not a successful trader. For some years as a Journeyman he earned a precarious crust. During the Chartist struggle of 1848(3) he was badly injured in defending himself – from an attack on the people by police on Clerkenwell Green. In 1855 he enlisted in 77th Foot Regiment, at the close of Crimean War he was discharged for ill health. He then married – of three children, Alfred survives.

apprenticed to a Bootmaker. And now mixing with workmen who are proverbially thinkers, he gained much useful information – entering into business before he was twenty one he was not a successful trader. For some years as a Journeyman he earned a precarious crust. During the Chartist struggle of 1848(3) he was badly injured in defending himself – from an attack on the people by police on Clerkenwell Green. In 1855 he enlisted in 77th Foot Regiment, at the close of Crimean War he was discharged for ill health. He then married – of three children, Alfred survives.

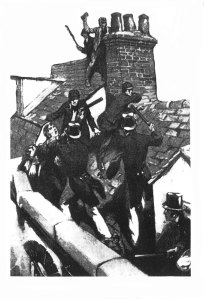

In the contest when the Hyde Park railings were thrown down he again got roughly used(4). These were rough times, a brutal Tory Government shut the gates – result, rails went down before an enraged people. For three days fighting was the order of the day. Secretary Walpole was snivelling to an Officer of the Guards. The second day, Sir Richard Mayne, Commissioner of Police, was tearing over the Park on his white horse when a well directed brick sent him flying heels up. His head thud on Mother Earth, that settled him.

As a member of the Council of Land & Labour League(5) he was called to move a second resolution at the great Torchlight Demonstration in Palace Yard, about 1870 or 71. Resolutions all passed by acclamation. A sea of heads from Charing Cross, Whitehall – right up to entrance of the Lobby of House of Commons. About same date Chatterton, by order, hired the large room of the Old Bell tavern in Old Bailey for a meeting in protest against any dowry to Princess Louise. The landlord on night of meeting locked the door, saying disloyalty was not his forte – W. Osborn invited the Friends to adjourn to the Hole in the Wall. There it was resolved to have a Monster Meeting in Hyde Park on the next Sunday. G. Odger(6) was Chairman. By stress of weather meeting adjourned to Trafalgar Square on Monday night, returning to Kirby Street. Inspector Clark served the organisers with prohibitory notice of meeting. At once bills were printed. Chatterton posted the west district(7), giving special care to Scotland Yard, serving the officials with a bill to as a Proof of Intent to hold the meeting at all peril. Charles Bradlaugh(8) spoke at that meeting in defiance of the Government.

Charles Bradlaugh(8) spoke at that meeting in defiance of the Government.

In the struggle for the Education Act of 1870 Chatterton was a member of London section of Birmingham Education League. In committee our old co-worker Thomas moved as Amendment to Resolution in favour of Unsectarian Education – one in favour of Purely Secular Education. It was lost in committee. At the big meeting at Exeter Hall Chatterton again moved his Amendment for Purely Secular Education. Patrick Hennesy seconded it – it got twenty votes in a meeting of 7000. He was well beaten, but today the world is easier – every loss is our ultimate victory. At G. Odger’s second lecture on Capital & Labour, at Kingston on Thames, Chatterton accompanied a party from the Hall of Science formed to carry out the meeting. Odger and Fagan at first visit were mobbed by three hundred well dressed roughs. A capital lecture was delivered on the Fairfield, Chatterton selling the literature of the party despite the efforts of aristocratic roughs to break up the meeting, but who were routed. During that summer Chatterton conducted a bookstall for the sale of Freethought literature for the Kingston Secular Party in Kingston Market. The last night of the season it blew a big hurricane. The lamp fell over and the Blasphemy was all ablaze. After a warm job Chatterton squelched hell fire in Kingston on Thames. The publications stowed away, Chatterton gave a lecture on Kingcraft & Priestcraft. A redheaded bigot opposed, he was backed by a howling mob. It was arranged that by signal comrade Chandler and a few sturdy friends dragged Chatterton out and escorted to railway station. That was lively.

In February 1880 Chatterton challenged Archbishop of Canterbury Tait to debate his assertion that Atheistic opinion led to moral degeneration. The Bishop made a lame reply by letter. This correspondence was inserted in the daily papers. The Sunday Observer made a caustic attack on Archbishop Tait for not knowing better than to debate with an Itinerant Spouter of Blasphemy – giving a splendid advertisement to Atheism.

On February 20th 1880 the Christian Evidence Society(9) held an annual meeting at the Egyptian Hall, Mansion House. Bishop Claughton, Chaplain of the Queen’s Army, expressed a wish to meet the Atheists. For furtherance of truth, C. Bradlaugh rose to speak. Alderman R. Carden ruled Bradlaugh out of order. He at once left the hall, then Chatterton essayed to reply. Bobby Carden ruled him out of order, sung the Doxology and closed the meeting. Resolved not to be defeated, Chatterton button-holed the Bishop as he left the platform, asking was God powerless to convince the Atheist? Turpin, Christian Evidence lecturer, brought a Police Serjeant. But Chatterton held his own, not leaving until the Bishop left the hall. Shortly after, Chatterton sent the Bishop a challenge, to debate the existence of God. The Bishop invited Chatterton to his house at Maida Vale. He went, was shown into a luxurious room. There for one hour did the Bishop and the Bill Sticker plead and paste God to their utmost ability. At parting, ‘Chatterton’, said the Bishop, ‘I am afraid, it is as you were. But give me a promise – should God bring you to himself, come and tell me.’ ‘Oh yes Bishop,’ said Chatterton, ‘I will promise that – aye, and give you some advice with it. Don’t you sit there until I get back, lest you get tired.’ that Bishop is dead. Archbishop Tait is dead too. Turpin CEL is dead too. But Agnosticism, Secularism, Materialism – all Atheism, the outcome of cultured thought, is live and rampant as ever. Possibly Chatterton will die too. Yet our Women and Men have built biographies that have crushed your faggot & stake into annihilation.

As the author of several Atheistical & Revolutionary Pamphlets, he has worked hard; in 1884 he started Chatterton’s Commune, The Atheistic Communistic Scorcher. The whole of his unique literary productions may be read at the British Museum Library. Today, realising all the grandeur of life that is worth living; the limpid gleam of love in his sister woman’s eye, the thrill of gladness in the grasp of his brother man. As he goes his way it finds him an old man in the actuality of three score eleven. Yet making cheerily for that other fifty. Wanting no God, no fear of hell, no aspirations for heaven. Standing in the throes of eternity now. Matter always was, he is, matter always will be. The aged frame feeble, yet head erect, eye clear, brain strong, looking lovingly into the forces of nature, the indestructability of matter.

Such is Dan Chatterton – Atheist & Communist.

Printed by Dan Chatterton.

29 Goldsmiths Buildings,

Drury Lane, W.C.

NOTES

1) Dorrington Street is now part of Mount Pleasant, WC1, in the area between Gray’s Inn Rd and King’s Cross Rd. An old street name for Dorrington St can still be seen there on the row of buildings next to the Apple Tree pub.

2) Chatterton’s father was an artisan japanner or furniture laquerer. But from his youth onwards, beginning with his father’s mental illness and diminished earning capacity, Chatterton and his family were to become steadily downwardly mobile in terms of economic means and social status.

3) 1848 was the last high point of Chartist struggles and Clerkenwell Green in Chatterton’s neighbourhood was the scene of numerous clashes between police and demonstrators.

(For further information, see Reds On the Green

4) The reference is to the massive July 1866 demonstration called by the Reform League (formed in 1865 to campaign for manhood suffrage and the ballot). The police attempting to deny entry to the Park via the gates, the protesters instead broke down the railings to gain entry.

5) The League was set up by a coalition of O’Brienite Chartists and members of the International Working Men’s Association (First International) in the 1860s to advocate land nationalisation. This is how Marx saw its relationship to the IWMA and the working class; “The English possess all material requisites of the social revolution. But they lack the spirit of generalisation and revolutionary passion. Only the General Council is able to inspire them with those qualities and thus to speed the revolutionary forces in that country and consequently everywhere. The only means to attain that object is to secure an unbroken contact of the General Council with English Labour. As General Council and Regional Council we can set on foot movements (as, for instance, the Land and Labour League) which appear in the eyes of the public as spontaneous manifestations of the English working class.” (Importance and Weakness of English Labour, Marx, 1869;

http://marxists.catbull.com/history/international/iwma/documents/1869/english-labour.htm)

6) Nineteenth century English trade unionist and member of the International Working Men’s Association.

7) For much of his later adult life Chatterton was a bill sticker – ie, employed to paste up poster advertisements on street walls.

8) A well known 19th century Atheist and reformer, founder of the National Secular Society (still in existence). Became MP for Northampton in 1880. Despite being elected four times, he was repeatedly blocked from taking his seat in Parliament – due to his demanding the right to be allowed to affirm non-religiously rather than swear the religious Parliamentary Oath of Allegiance. When refused the right to affirm he agreed to take the Oath instead: but that option was then blocked. Finally allowed to take the Oath “as a matter of form” or formality in 1886, in 1888 he secured passage of a new Oaths Act which granted the right to affirm instead of taking the religious Oath.

NB: Andrew Whitehead uncovered a letter of condolence sent by Charles W. Barker from Lavender Hill to Bradlaugh’s daughter on her father’s death in 1891:

“My opinion of your father is not unlike that expressed to me by old Dan Chatterton in August last. I made Dan’s acquaintance twelve or thirteen years ago under the St Pancras Arches, + since then have had many a free + easy conversation with him. He was looking very bad when I saw him last August: so I remarked “Dan; if you were to die who would bury you?” “That hardly concerns me” replied the old man “perhaps the parish thieves might put the old boy (himself) under the turf or he might be buried at Charlie Bradlaugh’s expense”. “Look here Dan” I remarked “I don’t see why you should think Bradlaugh would bury you. You preach doctrines the exact reverse of those he favours. You are a regular bloodthirsty, impractical old anarchist Bradlaugh is a methodicial revolutionist”. “That’s right enough” said the old man “+ many a wigging – many a wigging old Charlie (your father) has given me” but – + here the old man dropped his gay + reckless tone + put not a little rough pathos into his style “but old Charlie has given the old man (Dan) other things beside a wigging. When all the — — thieves hadn’t a crust or a good word for Old ‘Chat’, Charlie Bradlaugh could generally give the old man a dinner. Yes, my boy, Charlie’s has fed me more than once; + I believe rather than let the parish thieves touch my carcase, he’d bury me if I were to die before him.

‘The last words of the old man sound painfully now: for when I looked at him + called before my mind’s eye the stalwart figure of your father, I thought within myself “Well Dan we shall doubtless see whether Charlie Bradlaugh will or will not bury you” little thinking that whilst the old irreconcilable (Chatterton) continued to throw the shadow of his bent + wasted figure on my path, Charles Bradlaugh, massive as Dan is meagre, would be resting beneath a hillock from which no shadows of the dead beneath it spread themselves across the landscape.’

9) Founded in 1870 – and still in existence – to defend Christianity against Atheism. Has included scientists among its members.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

DAN CHATTERTON – Mat Kavanagh’s Memorial

Leaving out those great ones who have cut their niches in history, (the history of this country is rich in fore-runners of Anarchism) such as Godwin Shelley, and Owen, I propose to place on record some of the lesser known pioneers of the Anarchist movement. Of those of a proletarian origin, Dan Chatterton stands out as one who attracted most attention. In front of me as I write, is a cabinet photo of this tattle spare old man, who, in his day, was so well known in the parks, and every part of London where there were meetings of any section of the advanced movement. There he was, selling the current issues ‘Freedom’ and ‘Commonweal’, especially pushing the sale of his own tattle production ‘Chatteron’s Atheistic, Communistic, Scorcher’. (A full set is in the British Museum.) He usually created both sensation and amusement by rapidly announcing his paper as “an appeal to the half-starved, herring-gutted, poverty-stricken, parish-damned, inhabitants of this dis-united kingdom!”

This paper appeared in pamphlet form, whenever possible, in various kinds of type, and on varying kinds of paper. Through it ran his ‘Auto-biography of old Chat’ which is a history of the struggles of his time, and his frequent challenges to the Bishops and priests to debate.

Mrs Beatrice Webb (Lady Passmore), in her book ‘The Story of My Apprenticeship”, states that when she was rent-collecting under Mrs Olivia Hill in the Drury Lame district, Chatterton was one of her tenants. She says that he was reputed to have collected his type from printers’ dustbins, which he set up on his kitchen table, and his wife sat on the formes, in order to get an impression; for he had no machine.

Richard Whiting, in his once famous novel “No 5 John Street”, makes Chatterton one of his leading characters, under the nom de plume of “Old 48”, and says of his journal – ‘This journal, if I may be pardoned the digression, has no circulation, yet it supports “48”, as he supports it. It is bought as a curiosity at public meetings and usually by persons who have in view an inexpensive donation to the British Museum. Many who buy it make the transaction an excuse for offering the proprietor an alms. It has every note of singularity. It is printed on paper of a texture generally used for posters, and of the hue of anaemic blood. Its orthography is that of the first standard, its syntax aspires to the perfect freedom of the Anarchist ideal. Its is set up from a composite fount, suggestive of a printer’s dustbin, and containing so undue a proportion of capitals that sometimes they have to take service out of their turn at the end of a word.

“It might appear to have a large staff for no two of its articles are signed by the same name. “Brutus” writes the leader, “George Washington” supplies the reports of meetings; “‘William Tell” supplies reminiscences of the Chartist rising and “Cromwell” acts as agent for advertisements. To the untutored, however, these are but so many incarnations of one commanding personality. When “48” has written the entire number, he sets it up, and carries it to a hand printing press which Gutenburg would have considered crude. When the press happens to be in a good humour, he obtains a copy by the ordinary method. When it does not, he is still at no loss, for he lays the formes on the table, and prints each sheet by pressure of the hand. Earlier difficulties of this sort were met by the co-operation of his wife, now deceased. This devoted woman sat on the formes, and obtained the desired results by the impact of a mass of corpulency estimated at fourteen stone. Her death is said to have been accelerated by a sudden demand for an entire edition of a hundred and seventy copies descriptive of a riot in Hyde Park. These earlier copies are valued by collectors for the extreme sharpness of the impression.”

John Henry Mackay, the German Anarchist poet, wrote a novel of the London Socialist movement of the ’80’s called “The Anarchists”, in which there is a very good pen-picture of Chatterton.

“Chatterton, always of the poor, was always for the poor, and never shirked the fight. Original, and strong in character, he fought all his life for his class. Individualistic in temperament he believed that it was only in Communism that he could find liberty. A militant Atheist, he was too logical to reject a government in the skies and accept one on earth. He fought the politician as he fought the priest, for, as he often said ‘They were twin vultures hatched from the same rotten egg.’”

Chatterton has passed on: he lives only in the few books mentioned above. The poverty-stricken old fighter brings to our mind the words of William Morris:

“Named and nameless, all live in us;

One and all, they lead us yet:

Every pain to count for nothing,

Every sorrow to forget.”

(Mat Kavanagh, Freedom, February 1934)

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

See also Andrew Whitehead’s podcast walking tour around Dan Chatterton’s life

Leave a comment