“But sure your hair will stand on end when once I do begin, sir,

The dreadful story to relate of our most gracious King, sir,

How that a poison’d arrow, by some base plebeian hand, sir,

In his most sacred guts was intended to be cram’d, sir.

Hum, hum, hum, &c.

Bur, ah! the dark design!-what a blessing for the nation!-

Was happily discover’d while ’twas in contemplation,

For had it pierc’d his Royal paunch, he surely had been dead, sir,

Tho” possibly he’d not been hurt if it had struck his head, sir.

Hum, bum, bum, 8cc.”

In the last three decades of the eighteenth century, pressure for reform of the political system grew throughout Britain. The electoral system was entirely designed to reinforce the power of the dominant class, the aristocracy. Just a tiny fraction of the population had the vote, mostly wealthy, all men; traditional constituencies controlled by powerful landowners elected MPs, while many towns and cities had no MP. Many constituencies had tiny electorates; some had literally no residents.

From the 1760s on, a movement gradually evolved, campaigning for changes to this corrupt and loaded political system, calling for a wider franchise, more representative constituencies, secret ballots (to prevent the wealthy and powerful openly influencing the vote), and more regular elections to parliament.

An increasingly economically confident middle class launched the movement for political reform. Often well-educated and wealthy, but excluded from social status, from political power and influence nationally, and dependent on the political patronage of the nobility, the middle classes faced heavy taxation, as the aristocratic parliament blatantly targeted the middle class for revenue raising.

Hostility to the blatantly corrupt and self-serving elite built steadily through the 18th century, voiced by muckraking journals, and by a lively political culture of debate discussion and argument, in coffeehouse clubs, pubs and debating societies, through a century punctuated by riotous eruptions.

The middle class movement for reform expressed its campaign for reform through a rhetoric of rights and liberty, often couched in the language of traditional English freedoms, lost rights being denied by the monarchy and aristocracy, ‘freeborn Englishmen’ should be free from arbitrary tyrannical government. John Locke’s philosophy of ‘natural rights’ – the idea that all men were born with inalienable rights to life, liberty and property – was also drawn on by radicals like Richard Price to develop a political program calling for civil liberties and a voice in the government of the country for all. (Obviously ‘all’ still meaning ‘only blokes’ at this stage…)

While this reform movement was based in the rising middle class, this rhetoric struck a chord with classes and castes lower down the ladder, who had their own issues, many of them economic and social… Among the artisans, workmen, shopkeepers of London and other British cities, the reform movement helped spark a self-organised political culture, which would help form a nineteenth century working class movement. If for some of the leading reformers, the economic needs of political enfranchisement of the labouring classes was never really a priority, a growing working class saw opportunities to speak up on its own behalf.

The reform movement ebbed and flowed between the 1760s and the 1860s… A six-point program was drawn up which summed up the demands of the reform movement:

– Universal manhood suffrage

– Constituencies to have equal population

– Annual Parliaments

– Payment of MPs

– Abolition of the property qualification to become an MP

– The secret ballot.

These demands formed the basic program of the movement for political reform for a century.

While the Whig party in Parliament represented some of the more moderate positions of the reformers, the powerful interests of the upper classes successfully resisted any shift in political power.

The American War of Independence and the French Revolution of 1789 added new pressures. The American colonists’ victory over the British hEmpire and establishment of a republic, and the French Third Estate’s early success in curbing the power of their monarchy, inspired British reformers, to believe wholesale change in political representation was possible.

The French revolution sparked wide-ranging debate among British reformers, from the dinner parties and salons of the more refined, to the debating societies of London’s taverns and coffee houses.

For the British monarchy and establishment, the increasing violence of the struggle between the revolutionaries and the aristocracy in France provoked increasing fear – that those campaigning for social change in Britain might take a leaf out of the neighbours’ book and end up challenging, even deposing, their own king, George III…

From this ferment, from the reform campaigns, the sympathy for the French Revolution, the artisans and workers beginning to combine and question their own position, emerged a network of radical organisations, particularly in the growing cities of an industrialising Britain; at the heart of this network was the London Corresponding Society.

Founded in 1792, the Society organised the first working class organisation for political reform. It began working among London’s artisans and workers, holding meetings in taverns, and mass meetings on London’s open spaces. The Society worked with many middle class reformers, amidst a real climate for change.

But the campaigns for reform scared the ruling class. Legal and moderate as their demands and methods were, the change they asked for seemed like catastrophe to classes dyed in autocracy and privilege.

Across the Channel, the Revolution moved radically leftward, king Louis XVI lost his head to the Guillotine in early 1793, and many aristocrats had followed. There were fears that the ‘swinish multitude’ might rise up in Britain and of political reform in Britain developing in a similarly decapitous direction.

many aristocrats had followed. There were fears that the ‘swinish multitude’ might rise up in Britain and of political reform in Britain developing in a similarly decapitous direction.

A government that represented the monarchy, the aristocracy, the traditional class structures got busy to subvert and undermine the reform movement.

Although the reform movement was popular, government fears were probably exaggerated. This didn’t prevent the government from penetrating groups like the LCS with spies paid by the Home Office. And spying spurred on official panic, since one inevitable outcome of undercover policing is the need for product – to justify the expense and effort expended. So spies not only hype up the danger of the political movements infiltrated, but also often push them harder into illegal and radical moves to make crackdowns more likely and self-justifying their own pay-packets.

Prominent reformers were targeted, charged and arrested. Radical writer Thomas Paine had to flee abroad as treason charges were prepared against him. Leading London Corresponding Society leaders Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall, were arrested and charged with treason in 1794.

Whether the government was entirely behind the ‘plot’ that followed next, or took advantage of entrepreneurial spymanship, was never clear, but it centred around an alleged attempt to assassinate king George III.

There had already been one attempt on the King’s life, in 1786, by Margaret Nicholson, who had been committed to the Bethlem Royal Hospital as mad. As had John Frith, who had thrown a stone at the king’s coach in 1790. These were seen as individual acts of mad people.

But times had changed and scares had to be mongered.

The existing Sedition Act making it High Treason to attack the King had lapsed on the death of Charles II. A new Treason Act was therefore drawn up, and a new Seditious Meetings Act was passed to stop large groups meeting and stirring up trouble or publishing critical writings about the Government.

These ‘Gagging Acts’ were unpopular, rightly seen as aimed at preventing any opponents of the injustices of the Government from speaking up. The Treason Act made it High Treason to think or talk about killing the King; under the Seditious Meetings Act, it became a requirement to obtain a licence from a magistrate before any form of public political debate or lecture could be held.

Government spies inside the London Corresponding Society had probably identified likely targets to be next for accusations of treason.

The Pop Gun Plot

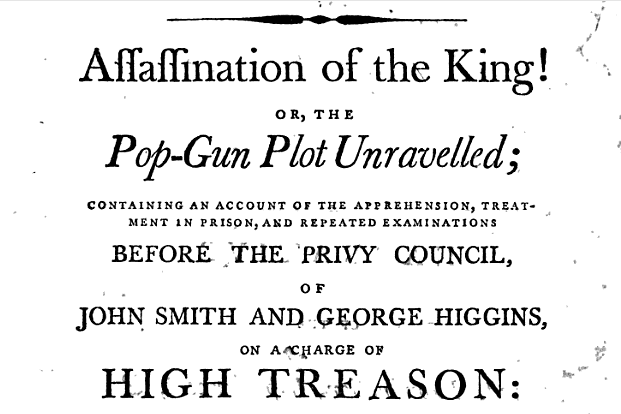

Several prominent LCS members, Paul Thomas LeMaitre, John Smith, George Higgins, and Thomas Upton, were arrested in September 1794, and Robert Thomas Crossfield’s arrest followed in August 1795. They were questioned about a plot to kill the king.

Smith was a bookseller who lived in Portsmouth Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields; George Higgins was a chemist; Paul Thomas Le Maitre, aged eighteen, worked as a gold watch case maker at his cousin’s house, 13 Denmark Street, Soho; Thomas Upton was also a watchmaker.

The government’s claim was that an attempt had been planned on the King George’s person by a marksman, who was to shoot the king with a high-powered air-dart gun. This had either taken place, or been planned to happen, in Covent Garden.

Lemaitre was “examined closely” by the Privy Council, “on the evidence of a forged letter”, for the next three days.

However, shortly after, the treason trials against Thomas Hardy, John Horne Took and John Thelwall collapsed in infamy when the radicals were acquitted in a blaze of publicity. The government strategy of repression looks like it was backfiring on them. The high profile acquittals may have made the government reluctant to charge and try LeMaitre, Smith, Higgins and Upton.

Upton had had a dispute with Lemaitre shortly before the arrest & had challenged him to a duel, which the latter dismissed as ridiculous. Upton seems to have been either considered suspicious or unpleasant by other reformers. After the argument with Lemaitre a motion was passed to expel Upton from the Corresponding Society.

It looks like Upton either turned kings evidence or was the instigator of the plot for ; he certainly gave statements which implicated others in a plot. He claimed financial assistance from the government until May 1795, asserting that his business had been ruined.

Hill, a woodturner and member of the LCS, told a fellow member in the week of the arrests that he had been visited by a stranger who asked him to make a wooden tube, which Hill feared was designed for a weapon, and told a fellow member after the first arrests that he was afraid this was supposedly for the ‘gun’ to be used in the assassination, and that he would also be arrested shortly.

James Parkinson, a Corresponding Society member who had written tracts published under the name ‘Old Hubert’, was brought before prime minister William Pitt and the Privy Council in October 1794, to be examined as to his alleged role in the plot. Accused of conspiracy, he refused to testify about his activities in the London Corresponding Society until he was absolutely convinced he would not incriminate himself in the alleged plot. He was released without charge and after issuing a last political article, ‘Vindication of the London Corresponding Society’ published no more pamphlets.

LeMaitre, Smith & Higgins were held in prison till May 1795, (during which time Lemaitre’s mother had died “of grief”), then released on bail of £200 each. Smith promptly renamed his Portsmouth Street bookshop ‘The Popgun’ and printed accounts of his, Higgins & Lemaitre’s detention…

The growing unpopularity of the war against France, which had sparked riots, and greater attendance at LCS monster rallies demanding reform, however, seem rot have inspired Pitt’s government to try and target reformers again.

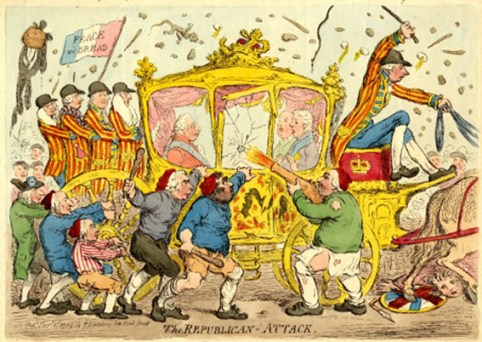

Events in October 1795 events re-ignited the ‘popgun’ charges. Shortly after a London Corresponding Society monster rally for political reform, on Copenhagen Fields, Islington at the State Opening of Parliament, the carriage of George III was set upon by an unruly mob. The besieging crowds cried for bread and chanted ‘Down with George!’, and ‘No King!’ One of

the carriage’s windows was broken in the ruckus. This was the opportunity the Government wanted.

They claimed the window was broken by a poisoned dart from the ‘airgun’, shot from some distance making it impossible to find the assailant, which had broken the glass on the carriage and had missed the King by inches. There was a terrible conspiracy afoot, and the London Corresponding Society were behind it. The spy the Government had placed within it could provide the testimony to convict the accused.

The popgun defendants were re arrested in January 1796 (although the charges against LeMaitre, Smith, Higgins and Crossfield clearly related to a supposed ‘assassination attempt’ a year earlier than the October 1795 agro!)

This spy was probably William Metcalfe, an attorney, and an informant who operated effectively within the London Corresponding Society. He was an elected clerk of the Tallow Chandlers Company, a position which he held by annual election until he was discharged on 5 September 1799 for financial irregularities. As an attorney he had been employed by the government in conducting criminal cases in the mid-1780s. Early in 1794 he began spying on the LCS and at John Thelwall’s lectures, for which he was to receive a sum of £300 per annum. His usefulness, however, came to an abrupt end in September 1794 when, at the request of the government, he was revealed as a spy during the capture of Lemaitre and the others. He and Upton were both present when LeMaitre was arrested at his home.

Lemaitre wrote and published an account of his arrest

You gotta love his stroppy self confidence (aged just 18!) refusing to be intimidated when being questioned by the highest in the land…

Crossfield had been arrested later and indicted as part of the plot in August 1795, when he returned from France, where he had ended up after a ship he was working on as a surgeon was captured by a French privateer.

Crossfield, Smith, Higgins and LeMaitre were finally tried for treason on 11 May 1796 – and acquitted.

The prosecution’s case was that the accused had conspired to employ wood turners and other craftsmen to make tubes which would be used for the dart gun. A number of artisans gave evidence that Upton and others had visited them in their workshops and asked them to make tubes and other suspicious parts. Other witnesses who had met Crossfield when he was in France or on board ship testified he had boasted about being part of a plot to kill the king with a dart gun.

However, Upton never appeared to give evidence – in fact he had disappeared. His wife said he had walked out of the the door one day and vanished, and the prosecution claimed he was dead (not sure if they were suggesting he had been silenced?). The defence on the contrary claimed Upton was very much alive… they claimed to have proof that he was living the we day before the trial – but never produced it. This was because the judge roughly warned the defence that they could not impugn the integrity of the prosecution by contradicting their assertion of his death, especially by calling any witnesses to the contrary, and especially not Upton himself ! (Yeah, work that one out).

Most likely, Upton had gone to ground, to avoid hostile questioning about his dubious role in the affair. In any case, much of the evidence related to things only Upton could be shown to have done or was to give evidence about, and without him the government’s case was weak, verging o nnone-existent. As the defence barrister pointed out, all the evidence relating to actual ‘tubes’ or soliciting the manufacture of them pointed to Upton as being the main or only mover.

The defendants were quickly found not guilty by a jury.

Here’s an account of Robert Crossfield’s trial

Whether Upton was a long term spy, had turned informer from fear or resentment, been leant on by the state, would never become clear.

It’s not impossible that there WAS a conspiracy of some kind – though whether dreamed up by Upton, either provocateuring or otherwise, or an actual genuine plot. Crossfield’s later history suggests he may have not been averse to a bit of conspiring. Crossfield later served as president of the London Corresponding Society in 1798, when repression and arrests were closing the Society down. By this time, a core of Society members were conspiring with Irish revolutionaries, forming themselves into secret United Englishmen branches, and plotting insurrection. Crossfield wrote an LCS address to the French which indicated radical support for a French invasion to bolster British revolution (this ended up being used as evidence in the trial of English and Irish radicals nicked that year on their way to France to gather support for uprisings…)

Both Crossfield and Lemaitre were present at an April 1798 LCS meeting called up to debate what the Society would do in the event of a French invasion: thus meeting was raided by the Bow Street Runners and both men arrested again. They would spend the next 3 years detained, in Lemaitre’s case at least, without any trial.

After his release Crossfield was later seemingly involved in clandestine radical meetings prior to Despard’s conspiracy for a radical uprising in 1802. He died later that year, aged only 44, and is buried in Hendon.

After being nicked in April 1798, Lemaitre was held in Newgate Prison on charges of treasonable practices. He was removed to Reading gaol in August 1799. The register recorded no verdict. It seems he may have just been held without trial (as the suspension of the law of Habeus Corpus now allowed the government to do).

The Times newspaper of 16th December 1800 reported Lemaitre had petitioned the House of Commons in forceful terms that he had been tried for High Treason and acquitted, no evidence having been produced against him, but had then been the first person confined in Cold Bath Fields Prison, Clerkenwell (used to hold a large number of political prisoners including various LCS members), where he suffered much bodily injury, and that he had been subsequently arrested and at length confined in Reading gaol where he now remained. But a vote in the House of Commons to decide whether his petition should be accepted went against him.

Lemaitre was apparently at liberty by September 1801 when he married Caroline Coe at Christ Church, Spitalfields ; they were “both from that parish.” Lemaitre died in 1864.

Smith seems to have been up in court again only 6 months after his acquittal, for publishing seditious texts: “The Trial of John Smith, Bookseller, of Portsmouth-Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Before Lord Kenyon, in the Court of King’s Bench, Westminster, on December 6, 1796, for Selling a Work, Entitled, A Summary of the Duties of Citizenship” relates how this resulted in a two-year prison sentence with hard labour.

James Parkinson, ‘Old Hubert’, who had given evidence for the defence at the trial, went on to publish , ‘An Essay on the Shaking Palsy‘, becoming the first describer of the neurological condition now named after him – Parkinson’s Disease.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

In the decades after the 1790s, the masses continued to agitate for reform, especially after the end of the French/Napoleonic Wars. The government again brought in laws to repress protest and used spies to penetrate and disrupt the movements for reform,

as they had against the London Corresponding Society.

Links

After a new agitation for reform in the early 1830s, the 1832 ‘Great Reform Act’ pretty much enfranchised the better off elements of the middle classes – while leaving the working classes out in the cold. But a new generation of radicals would continue the fight.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Bizarrely, this was not the last poison dart centred bullshit frameup plot by the British secret state aimed at knocking off the board radicals it considered dangerous during a major war… 120 years later, MI5 came up with the Alice Wheeldon case…

This time securing the jailing of radical activists for daring to protest and oppose the state’s murderous wars.

And state spying on protestors, campaigners, people getting together to fight for a better world, continues – into our own times and experiences…

Leave a comment