We remember… The Rotunda

The basis of this text was originally published in 2012, when the ‘Cuts Café’ squatted a building on the corner of Stamford Street and Blackfriars Road to use it as a campaigning centre against the government cuts and austerity onslaught… (we printed a brief account of the Rotunda, to distribute free at the Cuts Cafe squat centre).

We loved that the empty offices had been squatted for action! – not just because we passed that building regularly for years and thought it should be squatted (but were busy with other things!) … but also because they were reviving a powerful radical connection on that very corner…

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

No 3 Blackfriars Road, a now-demolished building which stood on the road’s west side, near the corner where modern Stamford Street now meets it, was once known as the Rotunda; for a few short years nearly two centuries ago, this was the most influential radical social and political meeting space of its era…

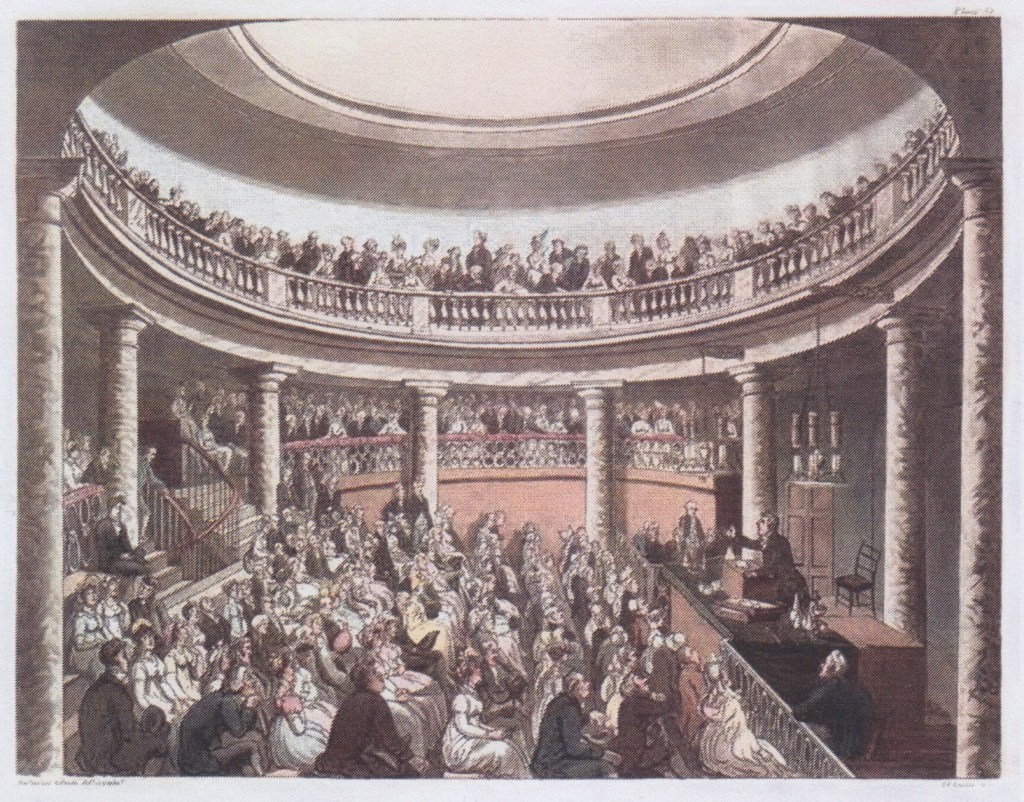

First founded as a ‘Freethought Coliseum’ and debating club, with a capacity of 1000 people, sometime in the 1780s, the Rotunda stumbled through various owners and numerous uses, until it was taken over by Richard Carlile in 1830, when it entered a brief golden age.

Carlile was a leading radical and freethinker in the 1820s and ’30s: famous/infamous, depending largely on how religious or orthodox you were politically, as a publisher and printer. He sold radical books and newspapers, concentrating on questioning religion, then a powerful influence over most people’s lives. Carlile was repeatedly jailed for re-publishing banned political works like the works of Tom Paine, and anti-religious texts, in a time when blasphemy laws were used regularly to silence anyone questioning christianity.

Carlile had also been at the forefront of the ‘War of the Unstamped Press’, in response to crippling government taxes on newspapers, designed to repress a huge explosion of radical and cheap newspapers aimed at the growing working classes. A huge movement evolved to produce, sell, smuggle these papers, evading a massive official effort to close them, through the 1820s and 30s… Carlile, and hundreds of others, were jailed, often over and over again, during this struggle, which ended with a victory, of sorts, with the reduction of the stamp, thus opening the way for a cheap popular press. From which we still benefit today (??!!)

Through the late 1810s, and the 1820s, Carlile had operated from several shops in Fleet Street, becoming one of the main focus points for a freethinking, radical self-educated artisan culture very powerful in London at this time… a culture that fed into the turbulent and rebellious working class movements of the 1830s and ’40s.

In the late 1820s, Carlile had been eclipsed slightly as the most notorious rebel and blasphemer; he was bankrupt, his book sales were declining, and the radical movements that had erupted after the Napoleonic Wars were temporarily fallen into decline.

But Carlile had a gift for thinking big and doing the outrageous… In May 1830 he spent the vast sum of £1275 (he was skint, so he borrowed the whole sum!) to rent the Rotunda as a venue lectures on atheism (although a fair chunk of this went on cleaning and a paint-job, as the building had got somewhat run down)… The Rotunda’s location played some part in Carlile’s choice of venue, being 200 yards north of Rowland Hill’s chapel (on the junction of Blackfriars Road and Union Street, where the famous Ring later gave birth to modern boxing), a leading centre of religious revivalism of its day. Carlile and his collaborator Robert Taylor saw the Rotunda as the perfect counter-blast to this famous chapel.

This was to be a public place where the disenfranchised and the disaffected could express their collective discontent. Landlords of pubs, taverns and other buildings often either refused radicals bookings, or had pressure put on them by the authorities to stop hiring places to such causes… No longer, Carlile thought, would the radical community be vulnerable to this. Carlile also hoped the Rotunda too could provide the ‘centre’ and a ‘heart’ for the real representatives of working people.

The Rotunda was to achieve this through popular dissemination of knowledge. A ‘war’ against the ‘ignorance of the whole country’ was central to his aims for the venture. He believed that working people needed, and wanted, a venue for ‘free, open and fair discussion’, but also a place of general instruction and learning for themselves and their children. Intellectual exchange unhindered by religious dogma or political orthodoxies, the ‘necessary purgation and purification of the public mind’, were necessary to build a movement capable of bringing in an inevitable new order of society. Carlile maintained that it was free discussion that was the ‘only necessary Constitution—the only necessary Law to the Constitution’.

It was not through direct political education that Carlile and his Rotunda allies initially envisaged effecting the necessary changes to society, but through science and reason… Carlile pledged that there would be ’no priestcraft, no despotism to deceive the people’.

In cahoots with Carlile, as least for a while was the ‘Reverend’ Robert Taylor, a former Church of England clergyman, who blended ultra-radical politics with a fierce opposition to religion. He was twice convicted of blasphemy, the first time in 1827 on an indictment for a blasphemous discourse at Salters’ Hall and on another for conspiracy to overthrow the Christian religion. Sentenced to one year’s imprisonment, at Oakham gaol he met fellow-prisoner Carlile; after they were both released they went on a four months lecture tour in May 1829.

At the Rotunda, Taylor preached in to large audiences dressed as a clergyman. Two ‘sermons on the devil’ in June 1830 gained him from Henry Hunt the title of ‘the devil’s chaplain.’ He was described him “over the middle size, inclined to be stout, and of gentlemanly manners”…

Taylor’s Rotunda lectures were multi-media extravaganzas, enhanced by 12 zodiacal emblems painted on the dome overhead, and a large board carrying greek ‘hieroglyphs’, a mechanical pointer, an expensive illuminated globe and a clockwork orrery… he was also sometimes accompanied by a female chorus playing guitars. His ‘Divine Service’ was offered on Sundays: a burlesque on bible, it usually started with readings from scripture, expanding into a satire on the Anglican service.

Taylor, unlike Carlile, leant strongly on theatre as a means of propaganda and saw it as a powerful lever of social change… They also disagreed on the demystifying power of satire and ridicule. Taylor’s Rotunda performances featured more and more burlesque and buffoonery, while Carlile always inclined to the more serious and moral style of lecture.

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

In 1830, southern England was rocked by the Swing riots: agricultural labourers smashed and burned threshing machines in a mass movement of riotous rebellion. The reputation of the Rotunda can be seen in the fact that Government ministers of the time blamed the Swing Riots on the influence of the Rotunda: this was certainly untrue, in that the revolts were sparked by immediate grievances. But the Rotunda was certainly feared by the powers that be. Taylor put on a play enthusing about the riots: called ‘Swing, or Who are the Incendiaries?’; but a year late the authorities got their own back, jailing Carlile for 30 months for defending the rioters in print.

The Establishment vs The Rotunda

In the early 1830s, there was growing pressure for parliamentary reform. A rough alliance of middle class and working class co-operated in pressing for a wider franchise, more representative constituencies, and other measures, to limit the power of the aristocracy… For a couple of years polite political reform, riotous workers and radical demagoguery all seemed to be part and parcel; of course in the end the 1832 Reform Act would later give the vote to the middle classes, who promptly ditched their plebeian allies with a fond fuck you all… Still it was a time pregnant with possibilities.

In November 1830, at the height of the Reform agitation, armed crowds met at the Rotunda, waving radical newspapers and attempted to march to Parliament:

“On Monday night (8 Nov 1830) a meeting was held at the Rotunda in Blackfriars road… an individual exposed a tricoloured flag, with “Reform” painted upon it, and a cry of “Now for the West End” was instantly raised. This seemed to serve as a signal, as one and all sallied forth in a body. They then proceeded over the bridge in numbers amounting to about 1,500 shouting, “Reform” – “Down with the police” – “No Peel” – “No Wellington.” They were joined by women of the town, vociferous in declamations against the police.”

The Duke of Wellington, then Prime minister, was the arch-champion of the most reactionary tories of the time, dead set against any political reforms or concessions to change of any kind. The class conscious workers movement especially considered him one of their main enemies. Note the flying of the French tricolour, the emblem of the first French Revolution, then still used by English radicals who took part of their inspiration from the events of 1789 in France. It was only really superseded as the main workers flag by the red flag in the later 19th century.

“The mob proceeded into Downing-street, where they formed in a line… A strong body of the new police arrived from Scotland yard to prevent them going to the House of Commons. A general fight ensued, in which the new police were assisted by several respectable looking men. The mob, upon seeing reinforcement, took to flight.

The refuse of the mob, proceeded in a body, vociferating “No Peel – down with the raw lobsters!” At Charing Cross, the whole of them yelled, shouting and breaking windows. They were dashing over heaps of rubbish and deep holes caused by the pulling down of several houses, when a strong body of police rushed upon them and dealt out unmerciful blows with staves on heads and arms.

In the evening another mob made their way to Apsley House, the residence of the Duke of Wellington, hallooing, in their progress thither, disapprobation towards the noble duke and the police. They were met by a strong force of the police, who succeeded in ultimately dispersing them. During the conflict many received serious injuries.

At half-past twelve o’clock, a party were in the act of breaking up [a paling], for purpose of arming themselves, when a body of police made a rush forward and laid unmercifully on the rioters, making many prisoners…”

The Duke Of Wellington considered the battle for the future of society as one of “The Establishment Vs The Rotunda.”

Two days later, the military besieged the Rotunda at ten o’clock at night trying to provoke another fight; they ordered Carlile to open the doors, but he refused, so they eventually buggered off.

More riots would follow the House of Lords voting down the Reform Act in 1831.

The National Union of the Working Classes

Despite the popularity of the Rotunda’s lectures, Carlile always had problems coming up with the rent for the Rotunda. Carlile tried to solve this by opening the space up to other groups, mostly radials, even ones he had previously quarrelled with or had serious political differences with.

In July 1831, he attempted to address this problem both financially and politically by letting part of the building to the National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC).

The National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC) held mass debates at the Rotunda; according to leading London reformer (and police informer!) Francis Place: “I have seen hundreds outside the doors for whom there was no room within.”

The NUWC had arisen as an alliance of groups of London trade unionists, many of whom were also sympathetic to the ideas of Robert Owen. However they largely rejected Owen’s belief that political reform was irrelevant, that the working class should organise only on the economic level. The NUWC instead maintained that political action was vital, that universal male suffrage, winning the vote for working men, would in the end bring about economic equality. They saw class relations as fundamental to society, and that in order to win their rights workers had to organise for themselves: some in the NUWC said the workers should organise themselves separately, in their own organisations. In London their support was mainly among artisans, who had formed the backbone of the reforming and radical movements, with a strong tradition of self-education, self-employment, apprenticeship and independence.

Membership of the National Union of the Working Classes totalled about 3,000 in London, they were divided into local ‘classes’ of 80 to 130 people, mostly in then solidly working class areas like Lambeth, Bethnal Green, Hammersmith and Islington. But their influence was greater than membership numbers suggest: especially through papers like the Poor Man’s Guardian, which were read widely among artisans and the emerging working class. In government and official circles, fear of the power and influence of the NUWC was, however, probably wildly out of proportion to its real power.

Some leading lights of the NUWC were George Foskett; William Lovett, later a moderate Chartist leader; Henry Hetherington, (who printed the debates in his ‘Poor Man’s Guardian’, the leading unstamped newspaper) William Benbow, James Watson and John Cleave, all three of who ran radical newspaper and book shops in London. Many had been linked to the ‘War of the Unstamped’ (see above). Most of these, and much of the membership of the Union in general, helped to create, or became involved in, the Chartist movement, a much larger expression of working class desires for reform, greater rights and power. The NUWC in many ways was a sort of proto-Chartism, though strong in London, where Chartism’s greatest strengths were in the new industrial cities of the north and midlands.

It was at the Rotunda that William Benbow first advocated his theory of the Grand National Holiday. Benbow argued that a month long General Strike would lead to an armed uprising and a change in the political system to the gain of working people. Benbow used the term “holiday” (holy day) because it would be a period “most sacred, for it is to be consecrated to promote the happiness and liberty”. Benbow argued that during this one month holiday the working class would have the opportunity “to legislate for all mankind; the constitution drawn up… that would place every human being on the same footing. Equal rights, equal enjoyments, equal toil, equal respect, equal share of production.” Benbow’s theory was published in a radical newspaper, the Tribune of the People, and in a pamphlet, The Grand National Holiday of the Productive Classes (1832).

From 1831 to 1833, weekly NUWC meetings and debates were held at the Rotunda; on and off; during this time there was an intense agitation nationally for reform, and many of these were heated discussions, as the Union was from the start to its end divided. There were arguments over definitions of class, over strategy and tactics, over the uses of violence, over whether to ally with the (then stronger) middle class political reform movement, or the more progressive wing of the Whig party.

Especially after the 1832 Reform Act gave voting rights to middle class men, but not the working class, some elements of the Union came to the conclusion that the lower classes would have to rebel to obtain their ‘rights’. There was a strong sense that the middle class reformers had used the threat of working class uprising as a stick to force the aristocracy to share power with them, then shafted their proletarian allies. Benbow made a speech celebrating the great reform riot in Bristol in 1831, but was opposed by other members of the NUWC Committee… Some NUWC members made plans to arm themselves in self defence against police attacks on rallies, which jacked up the government and bourgeoisie’s fear of the Union. By 1833, the moderates were beginning to desert the NUWC and the more desperate elements came to the fore. Their plan to launch a Convention of the People (a scary notion for the upper classes, coming straight from the most radical phase of the French Revolution) led to a rally on Coldbath fields in Clerkenwell, which was kettled and attacked by police. In the fighting a policeman was killed.

The NUWC began to fall apart after this, but its influence helped give birth to Chartism. Both the London Working Man’s Association and the London Democratic Association emerged from same groups and individuals in London, and they were crucial in kickstarting Chartism in the late 1830s. But its inherent divisions over class, whether workers could co-operate with the middle class, over the use of force, over the ultimate aim (just equality, or seizing power for the workers as a class), were inherited by the larger later movement, and continued to divide Chartism through its existence… And many are indeed questions alive and kicking in our own movements and struggles today…

Chartism. Both the London Working Man’s Association and the London Democratic Association emerged from same groups and individuals in London, and they were crucial in kickstarting Chartism in the late 1830s. But its inherent divisions over class, whether workers could co-operate with the middle class, over the use of force, over the ultimate aim (just equality, or seizing power for the workers as a class), were inherited by the larger later movement, and continued to divide Chartism through its existence… And many are indeed questions alive and kicking in our own movements and struggles today…

Carlile, meanwhile, had other problems… including a growing rift between him and Robert Taylor. Carlile disapproved of Taylor’s levity and clowning, and his wild behaviour, heavy drinking, and consorting with what ‘serious’ radicals saw as unsavoury characters, although he admired his ability to hold mass audiences. Taylor’s spoofs on religious services became wilder and wilder, he dressed as a bishop, parodied church services, and made more and more outrageous blasphemous comments on christian rituals or the scriptures. As a result he was hauled up in court in July 1831 for preaching blasphemy, found guilty, and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment in Horsemonger Lane gaol, with a hefty fine. His friends raised a subscription for him in September 1832.

This jail sentence actually caused a real split between Carlile and Taylor. Carlile thought radicals jailed for their ideas should be stoical martyrs: upstanding, unbending and morally correct. But Taylor was an unsatisfactory freethought martyr: he whined, wrote to the Prime Minister trying to get his sentence reduced, and got caught smuggling brandy into his cell.

Besides the NUWC, other noted radicals of the period graced the stages of the Rotunda: William Cobbett delivered a series of lectures on the French Revolution; in late 1830, the Irish ‘Liberator’ Daniel O’Connell chaired several NUWC meetings on the situation in Ireland.

Carlile’ s willingness to open the doors to a diverse range of radicals was not just from ideological motives – it also helped pay the huge rents and expenses. “Faced with the significant sum of £1000 per annum to keep the building open, Carlile also charged admission to the lectures and performances….

The Pythoness of the Temple

But even with the NUWC in residence, Carlile continued to struggle to pay the bills, and by late 1831 had rented the theatres (when not used by the NUWC) to a circus, a concert company and, on one occasion, a man exhibiting a ‘Phenomena of Nature’: a horse with seven legs. Given Carlile’s previous barbs regarding the flippant nature of popular entertainment, it must have stung deeply to see his prized venue reduced to a forum of trivial spectacle. Nevertheless, such performances kept the Rotunda open, allowing him to plan his next move…

In September 1831, he announced the arrival of a ‘new Jesus Christ who was to lecture at the Rotunda on Thursday evenings under various titles of ’Shiloh, ‘messiah’ and ‘Sion’. John ‘Zion’ Ward, a fifty-year-old crippled former shoemaker of Irish descent, had progressed through Calvinism, Methodism, Baptism, and Sandemonianism before becoming a follower of prophetess Joanna Southcott. In 1825, he experienced a ‘revelation that he was the new Shiloh, or Joanna Southcott’s spiritual offspring’ , aka Jesus Christ (though he had formerly been Satan). Ward’s millenarian Rotunda sermons, with titles such as the ‘Judgment Seat of God’, Balaam’s Ass and Fall of Man, enthralled Rotunda audiences. Ward adopted the mantle of Robert Taylor with ease, as his performances were also strong on countertheatre and melodrama; his lectures blended ‘rationalism, republicanism and chiliastic mysticism’. But despite attracting crowds of up to 2000 at the Rotunda, Ward left London to continue on their roving lecture circuit. Carlile was forced again to search for a star attraction.

But by January 1832, large placards were seen around London announcing a ‘new occupation of the building’: “a return to Taylor and Ward’s brand of Rotunda radicalism, only this time, sensationally, in female form.” Dubbed ‘Lady of the Rotunda’ and ‘Isis’ (derived from the romantic myth of the Egyptian Goddess of Reason), Eliza Sharples’s identity was concealed for many months to protect her family, a ‘mystery’ also designed to whip up interest and controversy, and in true Carlile-style was “promoted as intensely as an opening night at the theatre”, timed to coincide with a date auspicious to all radicals: the anniversary of the birth of Thomas Paine.

From a middle-class household in Lancashire, where she had largely educated herself and adopted freethought ideas, Eliza had come to London on hearing of Carlile’s imprisonment in 1831, visited him in prison, and became his (unmarried) lover. Convinced that Sharples would also invigorate Rotunda radicalism (and thereby his financial fortunes), Carlile took the bold step of evicting the NUWC from their headquarters in the larger theatre.

Eliza’s lectures became a ’regular strain of abuse of Religion, priests and all institutions.’ In the tradition of Taylor, Ward and Carlile, Sharples used the Rotunda platform to denounce the priesthood, mock religious superstition and pour scorn on established authority.

This aroused fury among conservatives and Christian evangelicals… The very fact that a woman was lecturing in public was considered ‘unfeminine’ in itself –the ‘blasphemous content’ of her talks compounded this. A correspondent to The Times, with a classic mix of misogyny and accent snobbery, labelled her a “female who exhibits herself in so unfeminine a manner… so utterly illiterate is the poor creature, that she cannot yet read what is set down for her with any degree of intelligibility…with her ignorance and unconquerable brogue…her ‘lecturing’…is almost as ludicrous as it is painful to witness.” Another report contemptuously described her as the ‘Pythoness of the temple’, branding her message as ’rubbish’ and suggesting retirement from the public sphere back to a domestic role, where, they supposed, she would more fittingly occupied as a “housemaid, or servant of all work, in some decent family…”

Sharples took up Taylor’s theatrical approach for his popular performances, for instance appearing wearing a ‘showy’ dress for her lectures, “stepping onto a stage strewn with the radical symbols of white thorn and laurel leaves”. On a stage previously occupied only by men, in a venue that was otherwise publicly associated with the rough, unrespectable elements of radicalism, appeared a woman in respectable dress, who then asserted the most unrespectable radical ideas… This was shockingly great theatre and provocation.

Richard Carlile had always aimed to establish the Rotunda as a space that catered for and attracted women, as other previous radical meeting spaces had failed to do. Police spy Abel Hall had reported large numbers of women attending Taylor’s lectures.

But Sharples tenure as a speaker at the Rotunda only lasted a few months. By February 1832, Sharples reported that over £1000 was needed to keep the venture open, to cover rent, taxes, lights, repairs, servants and to keep it in ’good order’. The Rotunda had teetered on the brink of closure ever since the imprisonment of Carlile. At the end of April 1832, facing an ever-widening financial burden, Carlile and Sharples took the dificult decision to end their tenure at the Rotunda.

Sharples would continue to work tirelessly in the freethought movement, publishing a secular magazine, Isis (no really!), and continuing to lecture on religion. She formed a link between the freethinkers of the 1820s-30s and the later large British secularist movement that evolved in the 1850s-70s, giving a home to the young Charles Bradlaugh, later to become a leading member of the secularist movement and a Radical MP, after his commitment to free thought led to alienation from his family.

Eliza McAuley

Shortly after Sharples’ tenure ended, the Rotunda again came under female management, when Eliza Macauley, a former actress and Christian turned Owenite preacher, took it over. In August 1832, Macauley established the Surrey and Southwark Equitable Exchange Bank on the model of Owen’s own National Equitable Labour Exchange, which operated a system whereby workers deposited their goods, and an exchange note was then issued, allowing the member to purchase goods in return. Macauley’s Exchange also allowed women to ‘add their industry to that of their husbands’ by issuing exchange vouchers for women’s labour.

Macauley also used the Rotunda premises to lecture on the equality of the sexes, financial reform and the superstition of established churches; women were admitted free. Macauley’s decision to lecture on a Sunday roused protestations from local Christians… She also planned to open a school of education and science for adults and an infant school in the Rotunda., but, the venture did not succeed and she became mired in debt. In 1835, Macauley wrote her memoirs from the Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison.

The demise of Macauley’s endeavour saw the Rotunda again return to an outlet of popular entertainment.

However, in 1842–43 the premises’ once again became a focal point for radical lectures. Again with a strongly Owenite connection with strong and a leading female presence. Harriet Martineau, radical-liberal, was reported lecturing at the Rotunda in November 1842. The Rotunda’s established history as a gender-inclusive venue for knowledge and instruction was also rekindled, as an Owenite Hall of Science opened there, providing classes to boys and girls, making no differentiation of subject matter based on sex.

Carlile, more of an individualist than a co-operator, took this development with wry amusement, joking that the ‘Socialists’ had taken over his Rotunda. ‘The Social Thieves of Lambeth’, he despaired, ‘have possessed themselves of my Rotunda! How I envied the rogues of Sunday!’ However he broadly approved that the Rotunda was again working for ‘public purposes’, noting that his friend George Holyoake, secretary to the Lambeth Branch of the Rational Society, was due to lecture there the following day. Holyoake wrote to Carlile, advising he had ‘elicited some warm cheers for you this morning at the Rotunda’.

The South London branch of the Chartist movement also held meetings there throughout 1843, with the ‘largest gathering’ since they ’obtained possession of the Rotunda occurring in July that year.

According to The Times of 17 August 1843, the Rotunda was crowded out after placards declared that the part of the queen in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, then playing there, was to be taken by “Miss Mary Ann Walker of Chartist celebrity” – a famous female Chartist (“notorious”, if you read the mainstream bourgeois anti-feminist and anti-Chartist press) When the queen appeared on stage and was clearly not the person expected, a cry went up of “No, no! That ain’t Miss Walker.” Despite an apology and explanation from the stage manager that the placards had been a hoax, the crowd howled and laughed through the rest of the play.

In late 1843, leading Chartist Bronterre O’Brien was lecturing there, and a soiree was held in his honour in the Rotunda’s large theatre in January the following year. In January 1843, the Examiner reported a meeting to appeal for the Repeal of the Corn Laws, which attracted a gathering of some 1500 people.

Holyoake proposed a subscription plan to allow the premises to be turned into a ‘Philosophical Institute’, with Owenite lecturer Emma Martin as director.

“Despite his reticence about the socialists and his Rotunda, Carlile might well have approved. As Barbara Taylor mused, the funeral sermon. Martin penned upon learning of Carlile’s death in 1843, which contained caustic attacks about the established clergy and Old Corruption, would have ‘warmed his own heart’.”

But though the subscription effort raised the required amount of £250, the landlord intervened in the plan, refusing to lease the building for ‘atheistical purposes’. The curtain had gone down on the most radical and blasphemous social space of its era…

Huge corporate developers St George have since engorged the site of the Rotunda with their erection of One Blackfriars, a skyscraper boasting 274 luxury flats, a “lifestyle hotel’ (whatever the fuck that is), and more sterile public space empty of meaning –

… But somewhere there’s a riotous crowd arming for uprising; and a man dressed as a bishop is mocking the absurdities of religion.

From the past to the present to the future: we have hung out on a lot of corners – that’s one of ours.

Originally published 2012, revised 2022

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

• Read more on the Rotunda, in

THE ESTABLISHMENT VS. THE ROTUNDA

a past tense pamphlet,

Which you can order here

Leave a comment