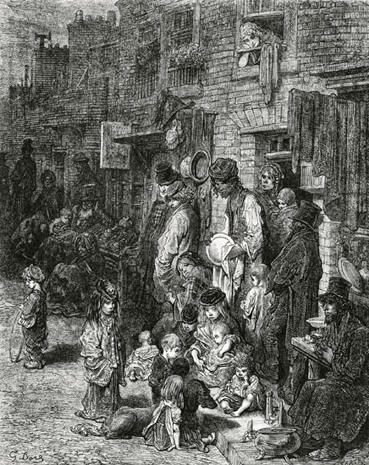

The winter of 1860-61 was grim: freezing weather and lack of work, leading to mass poverty among working people in London. ‘The district of Old Street, Goswell Street, Barbican, and Whitecross Street’, wrote a correspondent of the Morning Post on January 20, 1861, ‘are the boundaries, in a maze of courts swarming with people in a state of starvation.’

The low temperatures led to a lack of work: “Owing to the continuance of the frost, and all out door labour being stopped, the distress and suffering that prevail in the metropolis, particularly among the dock labourers, bricklayers, masons, and labouring classes at the East End, are truly horrible. Throughout the day thousands congregate round the approaches of the different workhouses and unions, seeking relief, but it has been impossible for the officers to supply one-third that applied. This led to consider able dissatisfaction, and hundreds have perambulated the different streets seeking alms of the inhabitants and of the passers-by.” (Morning Star, January 18, 1861)

“THE one domestic question at present uppermost in the public mind is the social condition of the humbler classes. It has been forced upon us by a winter of unexampled severity; by an amount of national distress, not at all exceptional in the cold season, which has gone to the very verge of bread riots; and by agitations in the press and on the platform for an immediate improvement in labourers’ cottages. The chief streets of the metropolis have been haunted for weeks by gaunt labourers, who have moaned out a song of want that has penetrated the thickest walls. The workhouses have been daily besieged by noisy and half-famished crowds; the clumsy poor-law system, with its twenty-three thousand officers, its boards, and its twelve thousand annual reports, has notoriously broken down; the working clergy, and the London magistrates, worn out and exhausted, have been the willing almoners of stray benevolence; Dorcas societies, soup-kitchens, ragged-schools, asylums, refuges, and all the varied machinery of British charity, have been strained to the utmost; and now we may sit down and congratulate ourselves that only a few of our fellow-creatures have been starved to death. The storm to all appearance has passed, but the really poor will feel the effects of those two bitter months -December, 1860, and January, 1861 – for years.” (Ragged London in 1861, John Hollingshead, 1861.)

The extreme poverty provoked collective action – proletarian shopping – taking the necessities of life by force without the politeness of paying. Over the nights of 15/16 January 1861, there were bread riots in Whitechapel.

Several bakers’ shops in the East End of London were emptied by a mob of 30 to 40 people on the evening of the 15th. The next day, things escalated: on the 16th, between seven and nine o’clock at night, thousands gathered, many of them dockers and their families, and cleared bakers’ shops and eating-houses. Outnumbered, the mounted police were powerless to stop the desperate spectacle.

“On Tuesday night much alarm was produced by an attack made on a large number of bakers’ shops in the vicinity of the Whitechapel Road and Commercial Road East. They were surrounded by a mob of about thirty or forty in number, who cleared the shops of the bread they contained, and then decamped. On Wednesday night, however, affairs assumed a more threatening character, and acts of violence were committed. By sonic means it became known, in the course of the afternoon, that the dock labourers intended to visit Whitechapel in a mass, as soon as dusk set in, and that an attack would be made on all the provision shops in that locality. This led to a general shutting up of the shops almost through out the East End – a precaution highly necessary, for between seven and nine o’clock thousands congregated in the principal streets and proceeded in a body from street to street. An attack was made upon many of the bakers’ shops and eating-houses, and every morsel of food was carried away. A great many thieves and dissipated characters mingled with the mob, and many serious acts of violence were committed. The mounted police of the district were present, but it was impossible for them to act against so large a number of people. Yesterday, the streets were thronged with groups of the unemployed, seeking relief of the passers-by. In the outskirts similar scenes were observed, and in some instances acts approaching intimidation were resorted to to obtain alms.” (Morning Star, January 18, 1861)

The bread riot was a not irregular feature of life both before and after industrialisation in England, with bread prices at the mercy of many factors including bad harvests, greedy price-raising by hoarders and artificial price-hiking in the interests of landowners by use of legislation like the Corn Laws. Although these laws had been repealed in 1846, economic slump or seasonal conditions could reduce whole areas to near-destitution. There had been bread riots across London in 1855, including in Whitechapel…

In the January 1861 riots, East End dockers were prominent: dock work was precarious and unstable at the best of times, with men engaged day to day at the whim of the gangmasters; frozen weather caused ships not to be able to be unloaded and work to slacken.

The grim conditions continued into February and March: “It is doubtful if there was not more real privation in February than in January of the present year; and the registrar-general’s return of deaths from starvation – the most awful of all deaths – for the mild week ending February 16, had certainly increased. There has been no lack of generosity on the part of those who have been able to give. The full purse has been everywhere found open, and thousands have asked to be shown real suffering, and the best mode of relieving it. A local taxation, cheerfully and regularly paid, of 18,000,000l. per annum, beyond the Government burden, is either inadequate for the purposes to which it is applied, or applied in the most wasteful and unskilful manner. The sum, or its administration, is unable to do its work. The metropolis, not to speak of other towns, is not “managed,” not cleansed, not relieved from the spectre of starvation which dances before us at our doors.”

(Ragged London in 1861, John Hollingshead, 1861)

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the 2020 London Rebel History Calendar – buy a paper copy here

Check out the 2020 London Rebel History Calendar online

Leave a comment