As previously recounted elsewhere on this blog, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the silkweavers of London’s East End were well known for organising collectively to defend their interests; often using violence if they had to. Their methods of struggle took a number of forms over the several centuries that the trade was strong in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green. Most often the journeymen weavers would be pitted against the masters, usually trying to keep wages high, exclude men working for less than the agreed rate, and sabotaging masters who paid too low… At other times organised violence was used to smash machine looms and threaten those using them, as the looms were seen as also lowering wages

Throughout the 1700s, successive waves of struggles, often turbulent, had kept mechanisation at bay and contributed to laws restricting imports of cheap textiles from abroad considered threatening competition. But by the late 1760s a long-running wage struggle between masters and workers had evolved into all-out war.

Trade fluctuations, widespread smuggling of silks and other pressures had led to widespread unemployment and reductions in wages in East London’s silkweaving districts by 1762. 7,072 looms were out of employment. This led to mass discontent among journeymen weavers, manifesting as attempts to raise wages and impose their Book of Prices, in which they recorded the piecework rates they were prepared to work for (an increase on current rates in most cases).

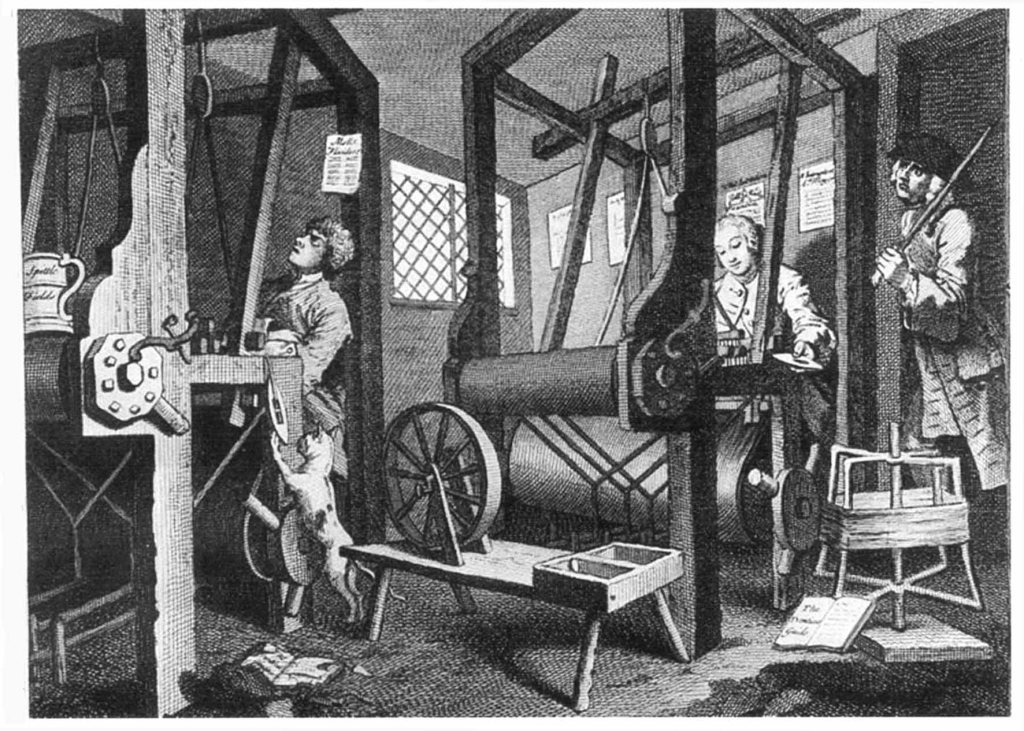

They had the Book printed up and delivered to the masters – who rejected it. Increasingly masters were turning to machine looms, and hiring the untrained, sometimes women and children, to operate them, in order to bypass the journeyman and traditional apprentices and their complex structure of pay and conditions.

As a result of the rejection of the Book, two thousand weavers assembled and began to break up looms and destroy materials, and went on strike. There followed a decade of struggle by weavers against their masters, with high levels of violence on both sides.

Tactics included threatening letters to employers, stonings, sabotage, riots and ‘skimmingtons’ (mocking community humiliation of weavers working below agreed wage levels: offenders were mounted on an ass backwards & driven through the streets, to the accompaniment of ‘rough music’ played on pots and pans). The battle escalated to open warfare, involving the army, secret subversive groups of weavers, (known as ‘cutters’ for their tactic of slashing silk on offending masters’ looms), and ended in murder and execution. Some of these tactics had long roots in local history and tradition – others could have been imported with Irish migrants from the Whiteboy movement in Ireland.

As a result of these riots, an Act was passed in 1765 declaring it to be felony and punishable with death to break into any house or shop with intent maliciously to damage or destroy any silk goods in the process of manufacture.

In 1767 wage disputes broke out again: masters who had reduced piece rates had silk cut from their looms. At a hearing in the Weavers Court, in November that year, a case was heard, in which a number of journeymen demanded the 1762 prices from their Book be agreed. The Court agreed that some masters had caused trouble by reducing wages and ruled that they should abide by the Book. However this had little effect, and trouble carried on sporadically.

In November 1767 trouble also broke out between distinct groups of workers: single loom weavers and engine looms weavers were now at loggerheads.

To some extent the machine loom weavers mentioned above can be described as identifying with their masters against fellow workers. In the ensuing fierce struggle of the cutters’ riots, organised weavers used intimidation and sabotage to disrupt the income of masters paying less than the agreed wage rate. Because of the nature of much silkweaving in Spitalfields, with piece-work often being allocated to workers weaving on looms in their own homes, these acts of violence inevitably meant targeting workers at home. This enflamed what seem to have been already bitter relations; the masters may well have been rubbing their hands at the angry splits opening up, as the prospects for lowering wages even further might have seemed rosy.

Although accounts of silkweavers’ violence often concentrate on the ‘cutters’ attacking looms of weavers accused of working for less than the rate, or blindly attacking machine looms, the machine loom weavers themselves were hardly passive victims in this struggle.

A month after machine loom weavers fought handloom weavers in Saffron Hill, another fight erupted on the edge of Spitalfields: an organised attempt by machine-loom workers to target others they accused of being behind recent sabotage of machine looms:

“On Sunday night great disturbances happened in Spital-fields, in regard to the masters having lowered the price of work four pence per yard; but at length a dispute arose among the journeymen, dividing themselves into two parties, when breaking of particular houses windows became general, several of whom were taken into custody, to be dealt with according to law, among whom was a publican charged as a ringleader in the affray….

“A large body of journeymen weavers well armed, having assembled on the Sunday night in Bishopsgate-street, they proceeded to the houses of many journeymen weavers, distinguished by the names of single-handed weavers, in resentment, as they declared, for the latter having been lately concerned in destroying the looms and works belonging to the engine-loom weavers. At these houses several of the journeymen single-hand weavers were seized by their antagonists and kept in custody most part of the night; but before morning they all made their escape, except three men, who were on Monday carried before Sir Robert Darling, knt. And George garret esq. at the Angel and Crown in Whitechapel. In the curse of a strict examination of the several parties, it appeared that the engine-loom weavers, who were the complainants, had acted in a very blameable manner, as they had not only assembled and taken people into custody without any legal warrant or authority, but that they had fired into several houses, and committed divers other illegal acts, to the great terror of many persons, and the disturbance of the public peace. Therefore, upon the conclusion of this examination,, which lasted near six hour (in which the magistrates, to their honour, acted with much discretion and impartiality) the above three men, who were charged with having been concerned with many others in destroying some of the engine-loom weavers works, upon giving sufficient security for their appearance, were admitted to bail, to answer the said charge at the ensuing sessions of the peace for county of Middlesex. The mob of journeymen weavers at both parties being the greatest almost ever known, during this long examination, obliged the magistrates to send a party of guards to keep the peace; and at the conclusion of the affair, the single-handed weavers carried off the above three men in triumph. And we are also informed, that the magistrates were unanimous in opinion, that no adequate remedy can possibly be applied to put a stop to these outrageous disturbances between the different branches of journeymen weavers, which threatens destruction to this valuable manufactory, until the legislature shall have established by law the standard prices of labour between the workmen in all the said various branches of business.”

A day later the army were sent in to ‘keep the peace’:

“Yesterday about noon, a party of guards was ordered to march from the Tower into Spital-fields, to preserve peace and good order in those parts, which so irritated a body of the weavers, that they foolishly opposed them, with old swords, flicks, and bludgeons, and even struck some of the soldiery, who were obliged to return the same in their own defence, by which several were slightly hurt on each side, and some of the offenders obliged to surrender at discretion, and were delivered over to the civil power.” (Annual Register, January 1768).

This wasn’t the last time the army was sent in to the area, as the above events heralded the cataclysmic struggles of 1768-69 (the ‘Cutters’ Riots’): a prolonged struggle, with bitter violence, rioting, intimidation of workers and threatening letters to employers, and hundreds of raids on factories and small workshops. Strikers in other trades joined in the mayhem: 1768. Crowds of weavers also forcibly set their own prices in the food markets, in defiance of high prices. It would end in shootouts in a pub, executions, and the revenge killing of an informer. But in 1773, the weavers would win a measure of wage protection, arbitrated by local magistrates, which would last for 50 years.

It would be interesting to pursue research here, into who each side consisted of. To some extent, over previous decades, long-standing communities in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green and neighbouring areas had faced competition for work from new comers. In the 17th century some English weavers had resented the arrival of large numbers of French hugenots, protestants fleeing religious repression in France. Later, this community itself faced cheap labour, as weavers fleeing poverty in Ireland migrated to East London. How much of the division between machine work and handloom work was ‘racial’ in this way I am not sure – though for sure resistance united the descendants of Irish and French weavers, some of whom were hanged side by side in 1769. I hope to look more into this when I can…

If you are interested in reading more about the Spitalfields silkweavers and their collective violence, our pamphlet Bold Defiance, is available to buy on our publications page.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2018 London Rebel History Calendar

Leave a comment