RARE DOINGS AT CAMBERWELL

A walk based on research done for a radical history walk around Camberwell, under the title “The Right To Live”, held on Sunday 25th June 2006, as part of Camberwell Arts Week. The walk was researched, designed and mostly spoken by Melissa Bliss and Alex Hodson, though other locals contributed their own reminiscences… In April 2007 part of this material was reprised as a talk at the Camberwell Squatted Centre (aka Black Frog) in Warham Street. We’ve run some public variations on the same walk since… This text owes much to the original researches and ideas of Melissa Bliss.

This isn’t the history of Camberwell. It’s not even the history of the events, personalities and movements that it covers. It is, at best, a series of linked themes, exploring some social history and the more disorderly and politically radical underside of SE5. It has serious omissions, could cover more social history, more on industrial development and those who worked in those industries; more on the different communities that have made their home here, and the conflicts they have experienced; more on madness and its containment, and especially more on recent gentrification and class. Maybe another time…

Also: we are not historians. We came to history as rebels and activists, fighting for a world where people’s lives, personal relations and survival are organised for our needs and desires, not for someone else’s profit. Our interest in history arises from a wider desire, to change the present collectively. The past, its links to the present and to a future we aspire to create, are not separate areas of study; the ideas and practice of rebellion against the authority of one class over another, and the methods of social control that class society develops to maintain itself, link history, our own battles in our own lives, and the visions of how we would live if we could freely choose. Some of us have lived in Camberwell, and have experienced some of this ‘history’ first-hand.

An earlier version of this text was also published as a Past Tense pamphlet, ‘Rare Doings At Camberwell’ in 2008.

When done as a physical walk, this route could take some time… it could be split up into sections. Walked backwards. Whatever.

START: CAMBERWELL GREEN

Camberwell has a deep and interesting past, full of working class struggles, radical, subversive and downright mad personalities, rowdy popular entertainment and some outbreaks of class war.

A brief Overview of Camberwell/ general history

Up until the 18th Century Camberwell was a rural village, based around St Giles Church Church, the Green, (scene of the annual Fair) and a spa and healing well, which was located up Camberwell Grove.

Some historians believe the healing well may have given the area its name, as they think Camberwell means ‘well of the crooked or cripples’. This chimes in with the local church being named for St Giles, patron saint of lepers. People expelled from the City of London for having leprosy may have settled here for treatment.

However it is also possible that the ‘Camber’ refers to an old settlement of Britons, who in the days of the Saxon conquest of Southern Briton called themselves Cumbri (in modern Welsh, Cymry’). This might be linked to neighbouring Walworth, thought by some to be named by neighbouring Saxons for the ‘Welsh’ (Britons) who lived there. The whole area might have been an enclave of older celtic communities…

The old medieval parish of Camberwell St Giles included Peckham, Nunhead and much of Dulwich. The parish was controlled by the Vestry; when the parish was replaced as an administrative body by the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell in 1900. In 1965 the Borough was amalgamated with the Metropolitan Borough of Southwark and the Metropolitan Borough of Bermondsey to create the London Borough of Southwark.

The popularity of the Spa gradually transformed the village into a place of middle class retreat, and farms were replaced by big houses up the hill… The area became more suburban during the 19th century, as London expanded; speculative building firms bought up land and built large housing estates.

Later in the Century, the class of persons living in area ‘went down’, especially after “workman’s tickets” on trains enabled the working classes to live further from their place of work. In common with many other areas of South London, large areas of Camberwell saw mass house building to accommodate newer working class residents. Many earlier middle class areas thus were transformed into working class neighbourhoods from the 1860s-70s – for example around Southampton Way and St Lukes.

The following population figures give some sense of the massive 19th Century growth of the area, though they represent the whole parish and not merely Camberwell the village/suburb:

Census for parish of Camberwell Population

1801 7,059

1841 39,868

1861 71,488

1891 235,344

In 90 years a few rural villages were swallowed up by the rapid expansion of the metropolis.

So who were these people who moved into the area, and where did they live?

In Booth’s Map of Descriptive Poverty, from Life and Labour of the People of London,1890, the relative social class of people living in various parts of the area was sketched out. You can get an interesting picture of what had become a suburb of London, and where people of different classes lived.

- South, up the hill, from De Crespigny Park, to the top of the hill at least, was upper class, and upper middle class, wealthy, almost exclusively.

- The middle classes lived all round Church St, the Green, especially in houses lining the main streets. Also middle class was Brunswick Park, the east end of where the Elmington Estate now is, Camberwell Grove, Grove Lane, Coldharbour Lane, and along Peckham Road.

- The next class down, a mix of the ‘fairly comfortable’ with others on ‘ordinary earnings’, can be found behind Daneville Road, round Wyndham Road and Medlar Street.

- Mixed areas of ‘some comfortable, others poor’ lived behind the modern magistrates courts and off D’Eynsford Road, round the west part of the modern Elmington Estate…

- The poor (’18 to 21 shillings a week per family’) clustered to the north of Camberwell Green, round the old Father Red Cap pub/Camberwell Road, and also to the north of Southampton Way, north of Commercial Road (now Commercial Way), and north of the Elmington. “A confusion of alleys and courts enclosed by Lomond Grove, Camberwell Green and Camberwell Road” was described as holding the chronically poor in the 1880s (Dyos)

- Very poor areas (‘Casual, chronic want’) were found behind the Cock in Cock Yard (behind the modern Tiger (formerly the Silver Buckle) pub), round yards between the southern bus garage and Denmark Hill, and also in the Sultan Street area (known as Camberwell Mill or Freemans Mill), off Wyndham Road. Several streets here – Crown Street, Wyndham road, Pitman Road, and Bethwin Street were said in the 1880s to be “of very bad character”…”The only policemen venturing there were very foolish policemen.”

- Interestingly though, there were no concentrated areas of the “lowest class, vicious, semi-criminal” as could be seen all over Southwark and Newington further north.

With some exceptions and accepting that this is a broad generalisation, it could probably still be said today that Camberwell New Road, Church Street and Peckham Road form a kind of border, and those who live to the south in the main are better off and maybe hang with a ‘higher’ social class than those who live to the north… Not entirely, and areas are more mixed now than in the past… But it has some validity.

Local industries: In the mid to late 19th century, the printing, small engineering, leather trades became widespread in the area, mainly in the north of Camberwell round Southampton Way, and where modern Burgess Park now lies. The old Surrey Canal that ran from Camberwell to the Thames through Surrey Docks helped stimulate a lot of local industrial growth, especially along its banks.

Revelry, Disorder, Space and Social Control

For centuries, Camberwell Fair was held locally, every August. First recorded in 1279, it moved from being held in ‘Gods Acre’, the immediate grounds of St Giles Church, to Church Street, opposite the Cock Pub (which was by the corner of Denmark Hill); by the 18th century it had moved on to the Green itself.

Originally held for three weeks, (9th of August to September 1st, the latter being feast of patron saint St Giles), by the 1800s the Fair, with it’s catchphrase; “Rare doings at Camberwell”, had been shortened to only 3 days – the 19th, 20th, and 21 August. Local farming had declined, and the Fair’s traditional rural economic functions (based around trade, but also hiring of agricultural workers for the year ahead) had eroded; the Fair now mainly featured drink and food, music, and acts, shows and performances, with a generous side helping of illicit sex, debauchery, and some robbery and violence.

Cheap food stalls of food, (oysters, pickled salmon, fried plaice, gingerbread) mingled with with junk and toy stands; side by side with exhibitions, animals that performed, or had bizarre deformities, plays, merry go rounds, shies etc…hawkers, pickpockets, jugglers, performers, magicians… People from all over South London flocked to the event, with carts, donkeys, old nags, offering rides, often the drivers singing songs or bantering with each other.

But the growing middle class of early 19th Century Camberwell hated this plebeian disruption.

“For these three days the residents of Camberwell were compelled to witness disgusting and demoralising scenes which they were powerless to prevent” …

Peckham Fair, in the same parish, ran every year for the 3 days following Camberwell Fair (namely 22nd – 24th August), and was a similarly troublesome – local authorities had to pay for extra policing for the whole week and passed this onto the parish ratepayers.

The two events attracted petty, and not so petty, crime. In 1802 at the end of Peckham Fair; a “numerous and desperate gang of pickpockets” robbed & assaulted respectable folk en masse as they were leaving the Fair. The gentry and middle classes attending the Fairs were seen as fair game (pardon the pun)…

There were constant attempts to control and restrict the fair and people’s enjoyment of it. Fairs at this time were a major source of moral outrage (think of modern objections to the Notting Hill Carnival every year).

However, the Fairs were a source of income for many of the poor and working classes, both legally, and through crime and the conning of fairgoers; there’s no doubt that it also brightened up people’s lives, an explosion of wild relief of the daily grind of poverty in a huge party.

There were several concerted attempts during the early 19th Century to shut the Fair down. In 1807 a Notice was pasted up:

“Notice is hereby given that no drinking, booths, unlawful exhibitions or music, will be permitted at Camberwell or Peckham Fairs. That the constables have strict orders to prevent all gaming, or seize and carry away all implements used or employed therein, and to apprehend all the offenders, and that no dancing or music will be permitted at public houses, which are required to be close shut at eleven o’clock at night.

By order of the magistrates.”

Apparently “officers from Union Hall Police Office and the Patrol from Bow St, attended… some trifling incidents occurred, but none of serious importance.”

In 1823, a Camberwell Vestry meeting was held to see what authority there was, in the form of an old grant or charter, to hold the Fair, This backfired, as evidence was produced in a Petty Session case to support its right to be held. In 1827, the Vestry managed to ban Peckham Fair for good.

Another attempt to ban Camberwell Fair in 1832 failed, but by 1855, the Fair’s days were numbered: a local Committee for the Abolition of Camberwell Fair was set up by leading residents, who pressurised the parish authorities into buying the Green, and closing down the fair, with the help of the police. The glee of one middle class historian is palpable: the Green was “encumbered for the last time with its horde of nomadic thieves, its coarse and lewd men and women and this concentrated essence of vice, folly and buffoonery was no longer allowed to contaminate the youth of the district and annoy the more staid and respectable residents.”

The Green, said before then to be a Waste, was bought from the Lord of the Manor, landscaped, turned into a ‘proper’ park.

The closing down of Camberwell Fair should be seen in the context of a widespread campaign in the early 19th Century, to impose social and moral control over the growing working classes. National government, local vestries and parish authorities, officials of most churches, and various bourgeois organisations such as the Constitutional Society and the Society for the Suppression of Vice, were broadly united in attempting to control and ‘reform’ the ‘immoral’ behaviour of the working classes, especially the poor, through encouraging/them forcing them into hard work, proper respect for authority and religion, and by attacking ‘vice’, disorder and immoral behaviour. This meant repression of ‘vice’ in the forms of pubs, prostitution, those who radically challenged religion or the political establishment.

Fairs, widely viewed as hotspots of immorality, disorder and in many cases satirical political plays and speeches, were a prime target. Not only this, but in an era of political upheaval and widespread radical agitation among the working class, any gathering of the poor was seen as dangerous. The open spaces where Fairs traditionally took place were also under attack, through the enclosure of commons, Greens and the increasing landscaping into parks, or development into housing. The physical alteration of space was seen as having a moral effect on the disorderly behaviour of the poor: proper ordered open space replacing ‘waste’ and common was believed to encourage respectability…

For local Vestries, the high cost of policing the Fairs and cleaning up afterwards were also a factor.

But the Green’s tradition as a place of entertainment and hedonism has continued. It has long been a site of public meetings, rowdiness, rallies, protests, and parties.

Not only in terms of its continuing use by street drinkers, who, as in many other parks have gradually reclaimed open space in defiance of those who would keep them socially cleansed and invisible.

Read a longer post on Camberwell Fair

Festivals and parties have also taken place on the Green over the years.

For instance: in June 1998, during Camberwell Arts Week, a Summer Solstice party was held, featuring a three-quarter size model of Stonehenge, made of fibre-glass. Several hundred urban pagans reproduced their own Stonehenge Festival… during which a slightly inebriated reveller fell against one of the stones and, as they were all roped together) nearly dominoed the whole lot!

From 2006-2008, the annual ‘Bonkersfest’ celebration of madness and creativity was held there (more on this later).

Here’s a temporary plaque we put up on the Green to remember Camberwell Fair (some fancier banners about the Fair hang on the railings these days)

CROSS THE ROAD TO THE CORNER WITH CAMBERWELL NEW ROAD, STOP OUTSIDE THE ‘CAMBERWELL SURGERY’

Poverty, Crime And Policing

Look over the road to Tiger pub:

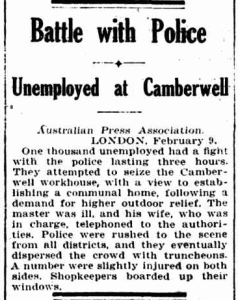

Tiger Yard and Joiners Arms Yard, behind the Cock Inn (ie behind the modern Tiger pub & the Joiners Arms) were among the poorest places in Camberwell in the mid to late 19th century… the people who lived here existed in chronic poverty. Large numbers of families living in a few houses, often unemployed and overcrowded. (These yards were still described as one of the area’s blackspots when demolished in 1930s. There had been much agitation by local Labour councillors to demolish the old overcrowded houses and rehouse the inhabitants, despite much opposition from the Tory-controlled Borough Council.)

There’s a great bit of research on the inhabitants of Tiger Yard before its demolition here

The bottom of the hill had always had some poor even when the area was rural; not all the forelock-tugging, law-abiding poor either. Some inhabitants who lived in cottages opposite the Cock Inn (round about Kennedy’s Sausages) were said to watch out for wealthy travellers dismounting from the coach, which stopped at the corner of Camberwell Green, and setting off walking to Dulwich… They would then follow them and lighten them of their possessions in some suitable dark spot…

This re-distribution of wealth led to the building of the constables’ Cage and Watchhouse, which stood on Denmark Hill, next to today’s Joiners Arms, until the founding of the Metropolitan Police in 1829. This was replaced as the stronghold of local law and order by a Police Station the Northwest corner of the junction of the Green and Camberwell New Road, (now the bank) which was built in 1848, and demolished in 1898.

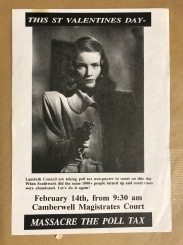

The Cage was succeeded by other centres of control and restraint. On the corner of Medlar Street and Camberwell New Road, Lambeth County Court used to stand, in the early 20th Century (with a Masonic hall and Sorting Office behind it, next to the railway). Camberwell Magistrates Court was built behind Camberwell Green in the early 1970s (we will return to this later).

Wyndham Road used to house the Southwark Diocesan Boys Shelter, in the late 19th/early 20th Century. This was an Approved Probation School for boys 16-19 put on probation in police court. The institution attempted to “build them up morally mentally and spiritually”, by prayer, a tough physical training regime, and training in domestic skills so they could better themselves by becoming servants in hotels and the homes of the wealthy etc. The usual mix of morality and brutality.

WALK UP CAMBERWELL ROAD TO THE NORTH: STOP AT THE CORNER OF WYNDHAM ROAD

Radicals and Rioters

19th Century Camberwell may have been largely a middle-class suburb but also had a local working class tradition: possibly originating in the tradition of London trades traveling out to rural pubs for days of merriment and sometimes political debate.

In the early 19th Century, with working people being increasingly forced off the land and into urban areas, with the growth of factories and massive spread of Cities, working class people were rapidly becoming politicised and conscious of themselves and their class interests. Working class organisations, radical clubs and early Trade Unions formed a growing network across many cities… London was no exception.

In 1832-3 the National Union of the Working Classes met weekly at the Redcap pub on Camberwell Green, and at the Duke of York pub, Camberwell New Road (which stood opposite the modern Union Tavern, but has long since been closed).

The NUWC had arisen from an alliance of radical artisan societies in London, who had been organising both on economic levels, fighting for better wages and conditions, and politically, seeing parliamentary reform and more rights for working people as fundamental to achieving economic improvements… The NUWC were involved in encouraging working class pressure in support of the campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act; however, the Act enfranchised the middle classes and reformed outdated constituencies and corrupt practices, but did nothing for the workers. More radical elements of the NUWC together with other groups, prepared to step up their activities – many felt armed uprising would be necessary to achieve change… This led to confrontations with the new Metropolitan Police, as at the Battle of Coldbath Fields in 1833, when a NUWC rally was attacked by the Met and a policeman killed in the ensuing riot (it was later found by a Jury to be Justifiable Homicide in self-defence, due to the police attack on the crowd!).

In 1833, the Sawyers Arms, Camberwell (which we haven’t yet located) hosted meetings of the 91st Class of the NUWC, in particular they held a dinner for the acquitted George Fursey, a defendant from the Battle of Coldbath Fields.

The Camberwell Division of the Union attended a meeting celebrating the anniversary of the 1830 French Revolution in July 1833 carrying their “beautiful large blue silk banner…. with a beehive and the bundle of sticks, hand in hand, with the mottos ‘Truth is our guide’, ‘Trial by impartial Jury’, ‘God and our Droits’, ‘Liberty and Justice’.” (Poor Man’s Guardian, July 1833).

The Chartists

As the 1830s went on, the NUWC and groups like them evolved into what has been called the first national movement of the British working class – the Chartists.

The Chartists aimed broadly at an increase in political power for working class people, at that time mostly not allowed to vote and formally excluded from the political process. Chartism became a huge broad-based mass movement, organised around six major demands for political reform that had been the program of the British reformers and radicals since the 1760s…

- A vote for every man twenty one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for crime.

- The ballot – To protect the elector in the exercise of his vote.

- No property qualification for members of Parliament-thus enabling the constituencies to return the man of their choice, be he rich or poor.

- Payment of members, thus enabling an honest tradesman, working man, or other person, to serve a constituency, when taken from his business to attend to the interests of the country.

- Equal constituencies securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors,–instead of allowing small constituencies to swamp the votes of larger ones.

- Annual Parliaments, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since though a constituency might be bought once in seven years (even with the ballot), no purse could buy a constituency (under a system of universal suffrage) in each ensuing twelvemonth; and since members, when elected for a year only, would not be able to defy and betray their constituents as now.

The Chartists’ tactics included huge monster meetings, and a petition to Parliament, presented and rejected three times between 1838 and 1848. The movement was made up of thousands of local branches, whose activities went far beyond pressing for reform, but built a whole culture, of education, songs, history, their own ceremonies and open discussion; they were conscious of their links to radicals of the past and similar movements abroad. and included all kinds of people, women and men, black people… Although most did not advocate the vote for women, some Chartists did, and female democratic associations formed an important part of the movement.

As their petitions and political pressure failed, many Chartists began to advocate a working class seizure of power by armed force, and divisions split these ‘Physical Force’ Chartists from their ‘Moral Force’ counterparts. Several Chartist uprisings were planned in 1839-40, which failed or were repressed. Plotters, and Chartists involved in organising rallies, strikers and other actions were jailed, transported to the penal colonies in their thousands.

Local Chartists who lived in Camberwell include one Simpson, of Elm Cottage, Camberwell, who sold tickets for a Chartist-sponsored soiree in honour of radical MP T.S. Duncombe in 1845; and David Johnston, a moral force Chartist, born in Scotland, a Weaver, then apprentice baker, who was elected Overseer of the Poor in St. Giles, Camberwell, 1831, ‘by popular vote’. Johnston ‘was a keen (moral force) Chartist. Johnston left in 1848 for the US, after ‘rowdies from Kennington wrecked my shop’.

The Chartists held mass meetings in South London the 1840s, mainly on Kennington Common, especially in 1848, the year of the last great Chartist upsurge, when they prepared the third Great Petition for the Charter. While the plans for presenting the petition were developed, physical force Chartists again prepared uprisings; in London in ’48 several riots ensued when rallies were attacked by police. Through the Spring and early Summer the capital was in a state of alert: the authorities feared revolution (which was breaking out in France and across Europe), and Chartists hoped and worked for a popular rising to achieve their rights.

On 13 March 1848, a week after a mass meeting in Trafalgar Square, that led to 3 days of rioting, a Chartist mass meeting was held on Kennington Common. Nearly 4000 police were called out; despite this 400 or 500 demonstrators moved off to Camberwell by back streets, led by a band. When they got to here, Wyndham Road, then called Bowyer Lane a riot broke out; looters armed with “staves of barrels, and sticks of all descriptions”, including palings, rifled shops and fought with the constables. The whole episode occurred within the space of an hour and only nine arrests were made (by a party of’ mounted police, assisted by special constables) at the time, but since a number of the rioters had been recognised by the locals twenty-five were brought to trial in April. Identified among the leaders were Charles Lee, a gipsy, and David Anthony Duffy, a ‘man of colour’ and unemployed seaman, known to the police as a beggar in the Southwark Mint, where he went about “without shirt, shoe, or stocking”; and Benjamin Prophett, known as ‘Black Ben’, another ‘man of colour’ and seaman. These and fifteen other men, of whom four had previous convictions, were sentenced to from seven to fourteen years’ transportation and three to one year’s imprisonment. More on the Camberwell Riot

The Camberwell riot was short, but it attracted some publicity, and contributed to the hysterical prelude to 10 April 1848, when Chartists met nationally on Kennington Common, aiming to march on Parliament. Shocked by the rebellious atmosphere in London and the country, the Government had fortified the bridges over the Thames and brought in the army and recruited middle class volunteers to defend them. The Chartist leaders backed down from confrontation.

Note the participation of black radicals in the riot: the early 19th Century radical movement was notable for the involvement of prominent activists of African descent. One of the leaders of the London Chartists, prominent in the April 10th events, was William Cuffay, a Black tailor whose father had been a slave from St Kitts in the Caribbean. Cuffay was arrested in June that year accused of involvement in the planning of a Chartist Uprising and transported to Tasmania for life.

Other Black radicals well known in South London was Robert Wedderburn, ex-slave, who had come to England, become a Methodist preacher, and then got involved in radical politics. Wedderburn used to preach on Kennington Common. His contemporary William Davidson was executed for taking part in the plans for a radical uprising in 1820.

A plaque we left here to remember the Chartist Riot of March 13th 1848.

After the anti-climax of 1848, the Chartist movement began to go into a decline; although many groups still existed, the Chartists were largely a spent force. Smaller groups of radicals continued to agitate and meet, but mass agitation for reform did not revive till the mid-1860s, when the National Reform League formed and many local reform-minded groups began to spring up. From this pressure came the 1867 Reform Act, which won some limited increase in the franchise for working men.

Liberals and Radical clubs agitating for once again became widespread in the 1870s, many emerging under the influence of the Secularist Movement, others from growing Republican agitation.

WALK BACK DOWN CAMBERWELL ROAD TO CORNER WITH CHURCH STREET

Secularists and Republicans

The Secularist movement arose from scattered radical groups, many of which had survived the collapse of Chartism, others of which emerged in the reform agitation of the 1860s. Influenced by powerful speakers like George Holyoake and Charles Bradlaugh, they discussed, debated and attacked the religious control over many aspects of people’s lives, much stronger and integrated into all walks of social, working and home life then. Secularists spoke at street corners, often in direct competition with Christian preachers, and formed clubs or branches of Bradlaugh’s National Secular Society. Gradually they also became associated with pressure for the right to birth control, and a strong republican strand, demanding the removal of the royals and a British Republic. More on South London Secularists

In the 1870s Camberwell Church Street was a local Speakers Corner: Secularists used to regularly denounce religion in large open-air meetings here. The area in fact became one of their strongholds – the Camberwell National Secular Society branch, an offshoot of the large Walworth branch built a hall at 61 New Church Road in 1882.

The struggle against religious charlatans exploiting the vulnerable is very much alive and kicking. In March 2021, charity regulator the Charity Commission took over administration of the highly dubious Kingdom Church in Camberwell Station Road, after local newspaper, the Southwark News exposed the church for selling ‘plague protection kits’ during the first Covid lockdown.

The commission launched a probe in August 2020 in response to concerns over the organisation’s finances.

“The inquiry’s remit includes looking into the trustee’s management of the charity’s resources and financial affairs, including the potential for funds to be ‘unaccounted for and misapplied’.

In a statement published in March 2021, the commission confirmed that it had “serious ongoing concerns” about the charity and its relationship with two subsidiaries, World Conquerors Christian Centres and The Kingdom Church.

Regulators say the charity does not have a bank account, with its funds instead being deposited in its subsidiaries’ bank accounts.

Both subsidiaries have been removed from the charity’s control – with regulators trying to ascertain whether this was done lawfully.

As the News first reported in August 2020, Bishop Climate Wiseman from Bishop Climate Ministries, part of The Kingdom Church, was advertising £91 COVID-19 ‘cures’.

The bishop went on to defend his actions, saying he could not deny the healing power of the almighty, but later slammed this newspaper as ‘the antichrist’.

Virginia Henley of Hewitsons LLP was appointed as interim manager of the charity under the Charities Act 2011 on February 15, 2021, to fully review the organisation’s future. The commission’s inquiry also continues.

The National Secular Society had reported the church to the commission over its ‘plague protection kits’. Its head of policy and research, Megan Manson, said: “This is a welcome intervention from the Charity Commission. This church’s future as a registered charity is now being questioned, and rightly so.

“All charities, including religious charities, must be held to account when they engage in unethical and harmful behaviour.””

The United Republican League held Sunday morning meetings in Church Street (and afternoon ones in the Rose & Crown Pub, Acorn Street in Peckham) in the early 1870s, when republicanism was very strong among the working class, and the Royal Family very unpopular. Famous class warrior Dan Chatterton spoke here.

There were also three Radical Clubs in Camberwell in the later 19th century – one in Denmark Hill, one in now vanished Muswell Road (not sure where this was), and North Camberwell Radical Club, in Albany Road.

For more on North Camberwell Radical Club – see Mayday in South London

There was also a Camberwell Radical Club in ‘Gloucester Road’ (possibly Gloucester Grove, SE15?) in the 1880s: William Morris was listed to speak there twice in 1885-6.

CROSS ROAD, UP EAST SIDE OF CAMBERWELL ROAD JUST AS FAR AS CAMBERWELL PASSAGE: THERE USED TO BE AN ENTRANCE TO TRAM DEPOT HERE.

War and the Workers

Camberwell Trades Council, representing local trade Unionists and Union branches, was founded in 1913. Almost immediately it was thrown into the political hotbed with the outbreak of World War 1.

Despite a sustained campaign against the impending war in the months running up to its actual outbreak, most trade unions and Labour Party activists fell in behind the government and supported the national war effort. The war achieved instant popularity, and thousands of men enlisted enthusiastically. Camberwell was said to have provided a good response to the call-up (though nearby Brixton was described as “full of slackers”!)

However, Camberwell Trades Council, in common with a minority of socialists and union activists, took an anti-war position when war broke out. The Trades Council issued pacifist leaflets, including a leaflet calling for people not to worry about paying rent during war, as surely landlords wouldn’t evict people during such a national emergency! The police tried to suppress this leaflet – unsuccessfully.

The Trades Council held meetings about the high cost of living, denouncing privations caused by the War, and launched campaigns for free school dinners for kids; useful work for the unemployed and democratic control and distribution of food.

In 1915 it also founded a Trades Council bakery, officially to try and increase the distribution of bread to the local working class; unofficially the bakery also provided jobs to conscientious objectors on the run from the authorities trying to force them into the army. Although this project collapsed by end of year, its work was incorporated into a similar bakery scheme run by neighbouring Bermondsey Trades Council.

In 1916, when the Government introduced conscription to force men into the trenches, Camberwell Trades and Labour Council also expressed its strongest opposition. It declared conscription in any form “to be a violation of the principle of civic freedom hitherto prized as one of the chief heritages of British liberty.” Anti -conscription demonstrations were held on Peckham Rye and on Camberwell Green by the Trades Council and ‘The No Conscription League’. One motion passed by a mass meeting stressed: “Conscription would be against the best interests of the working class and would be a strong weapon in the hands of reactionaries to enslave the British People.” Trade unionists were outraged when Military Tribunals were set up under the oversight of Borough Councils to hear claims for exemption from conscription. Trades Unionists were in most places appointed to take part in these borough tribunals, but then Tory-controlled Camberwell Borough Council refused to appoint any.

The Anti-war movement locally centred around the Independent Labour Party. Some ILP delegates followed the Christian, pacifist line of George Lansbury. Some were inspired by the ethical conviction that violence, organised or not, was evil and immoral. Others argued against the War on on socialist, internationalist grounds.

Leaders of anti-war activity in this part of South London included Charles Ammon, a member of the Fawcett Association, the postal sorters union, and Parliamentary Secretary of the ‘No Conscription League’ (he later became Lord Ammon of Camberwell), Dr Alfred Salter, (later to become MP for Bermondsey), and Arthur Creech-Jones, twenty-three year old Secretary of Camberwell Trades Council. In 1916 Creech-Jones was called up for army service. On appeal he attended four Tribunals and although supported by Labour Party leaders Fenner Brockway and Herbert Morrison his appeals were dismissed: he was finally arrested in East Dulwich in September. After being taken to the local Recruitment Centre, then based at Camberwell Baths (in Artichoke Place), and refusing to take orders, he was sentenced to three years imprisonment in Wandsworth and Wormwood Scrubs Prisons.

Creech-Jones gained much support in the local press. One letter from the National League of the Blind, Camberwell Branch praised his Trades Council work. When he was jailed, he was replaced as Secretary by Florence Tidman, delegate from the Women’s Labour League. Many trade unionist soldiers had returned from the front and were now becoming sympathetic to pacifism and opposed to the war.

Not all Trade Unionists locally opposed the War however. In March 1917 the local branch of the National Society of Operative Printers and Assistants disaffiliated from the Trades Council, disagreeing with its anti-war position. Many trade unionists reflected the jingoistic and pro-war/anti-foreigner feeling as the wider population they lived among.

The majority of the local population capitulated to the upsurge of national chauvinism. Camberwell, like many areas of London, had a small german population, often proprietors of small bakeries and other shops – there were German delicatessens, toy shops and haberdashers, and other local shopkeepers proudly announced that ‘hier spricht man Deutsch’. Others worked as music teachers, artists and waiters. There were around 60 German families in the area in 1914.

But many Germans were detained when World War 1 broke out (although some exiles had fled political persecution in Germany, or were descended from political refugees.) Racist hysteria against the “Hun” was whipped up to a crescendo in South London. Riotous mobs burnt and looted shops with German names in East Street, Camberwell Green and the Old Kent Road in October 1914.

The South London Press in early July 1916 reported a heavily underlined banner headline extending across seven columns proclaimed “Camberwell’s Great Patriotic Festival.” Seven miles of cheering crowds, we read, lined the streets to bid farewell to Lieut.-Colonel Hall and the men of the Borough of Camberwell Gun Division as they marched off for training.

Camberwell Borough also played host to Belgian refugees, driven out of their country by the German invasion. 300 were sleeping in Goose Green public baths in October 1914.

In May 1915 anti-German rioting resumed across the country after the ship Lusitania was torpedoed by German u-boats, with the loss of many lives. Sometimes the ‘foreigners’ targetted were not german, due to various levels of stupidity and bigotry intermixing. Frederick George Jeffreys, a 22-year-old plumber’s mate was fined 40s plus 10s compensation for smashing up a hairdresser’s shop in Wyndham Road, Camberwell in May 1915. The Lambeth magistrate H.C. Biron was scathing: “You behave in this way, and instead of attacking a German you attack a perfectly harmless Pole and wreck his shop. Even if he were a German you bring discredit upon your country by behaving in this way.”

Opposition was growing to the war, however, often in small local meetings across the country. At the Surrey Masonic Hall, Camberwell New Road, in June 1915, Charles Trevelyan MP addressed the South London Ethical Society: “The peace, when it did come, should not be made by diplomats sitting in secret, but there should be a real public opinion for the real ending of war on the right lines.” He warned his large audience not to listen to the militarists who claimed the time was not right for discussing the terms of peace. “They would keep on saying this until the last shot was fired.” Trevelyan had been a founder member of the anti-war Union of Democratic Control, established the previous year.

Check out Against the Tide, an excellent book on World War 1 and resistance in Southwark, Bermondsey and Camberwell.

Mutiny!

At the end of World War One, there was widespread social unrest. Disillusionment with the war increased across the country, as conscription and mass death had hit home, but repressive conditions at work and wage depression led to an upsurge in strikes. The Russian Revolution in 1917 inspired workers across the world to believe a new more egalitarian social order was possible. The unrest spread to the various armies, and mass mutinies helped to end the war, sparking revolt and revolution across the world.

Camberwell was affected by this ferment…

In January 1919 Army Service Corps men in a camp somewhere in Camberwell went on strike, during a mass movement of mutinies and demonstrations to demand faster demobilisation of troops all over Britain and in the army abroad. Despite some investigations we’ve not discovered where this camp was, whether in the Borough or SE5 proper… though theoretically it could be somewhere near to the present Territorial Army Barracks in Flodden Road.

In 1920, the British Government’s determination to send troops, including conscripts, to Russia to try to overthrow the new Soviet state, led to a mass movement inspired by socialists and trade unionists who were sympathetic to the Russian Revolution, to prevent troops and supplies reaching Russia. Local councils of action formed to oppose the move, and actions included dockers refusing to load goods and munitions for these ships. In August 1920, the Camberwell Council of Action demonstrated on Peckham Rye, where it called for “complete trade and peace with Russia”, and demanded that the National Council of Action send an ultimatum to Lloyd George along these lines.

The 1926 General Strike

In May 1926, the leaders of the Trades Union Congress called a General Strike. Nearly 2 million workers all over the country joined the strike, in support of a million miners, locked out by mine-owners for refusing to accept wage cuts of up to 25 per cent, after the ending of the Government’s coal subsidy. The General Council of the TUC didn’t want to call the Strike: they were pushed into it for fear of losing control of the mass of union membership.

Nine days later, afraid of the losing control of the situation, in the face of massive working class solidarity, the TUC General Council called the Strike off.

The General Strike was a massive defeat for the working class. The TUC General Council capitulated; many of the strikers were forced to accept lower wages add conditions: the miners in whose support the Strike was called were eventually starved into submission.

Locally Trades Councils or Councils of Action co-ordinated the union branches and workers involved in the Strike.

Camberwell Borough Council fully supported the Government against the strikers, it was cooperative with the Emergency Powers Act and its functionaries, and it appointed the Treasurer and Town Clerk as the officers in charge of food and fuel. This contrasted with other local boroughs eg left-wing Bermondsey, where the local Council supported the Strike and opposed the Government.

Camberwell Trades Council organised the Strike locally. According to a post-Strike Report by the Trades Council:

“only a fortnight before the strike, [we] obtained a roneo duplicator and a typewriter. When the possibility of a strike loomed up we made three tentative preparations for this eventuality, viz:

(a) We enquired for an office, which we might take for a month as a minimum.

(b) (b) We obtained a lien on a hall where we might have a large meeting and would run no danger of the hall being cancelled by opponents.

(c) We made arrangements for a Committee meeting to be called the day after the general Strike began, if it did so begin. On May Day we thought the importance of demonstrating was sufficient to warrant us paying for a band, banner bearers etc, and for us to give a lead in having a good turn out. This we had organized and we secured a fine response from Camberwell workers. Whilst on route to Hyde Park came the news of the General Strike declaration – truly a fitting send off, thus demonstrating to the rich loafers in the West End out power and solidarity.”

The Strike Committee organised effective picketing of workplaces. Tramwaymen and busmen, who made up 3000 of the 8000 workers affiliated to the trades Council, were solid, as were roadmen of the Borough Council also came out, (bar one depot where men were reported working.) Tillings Bus Co., however, of Peckham, a major local employer, was a black spot: large numbers of police specials were stationed to ensure these buses were never stopped from running.

Reports which came to the Strike office as to the need for pickets were transmitted to the Strike Committee concerned at once by an organised messenger network.

The Trades Council concluded that: “we were not ready. We quickly improvised machinery… Everything had to be found on the spur of the moment, and we rose to the occasion fairly well in our own estimation., considering the difficulties of lack of our own premises, voluntary workers, and having to set up, equip and run an office after the Strike had commenced.”

In the Borough of Camberwell, as it was then, two strike bulletins were produced, the Camberwell Strike Bulletin and the Peckham Labour Bulletin – both produced from Central Buildings, High Street, Peckham.

The South London Observer of Saturday May 15th reported that a man was convicted of selling the ‘Peckham Labour Bulletin’. The paragraph headed “French workers refuse to blackleg” was thought by the court to be provocative. Police Inspector Hider in his evidence stated that it would cause “a certain feeling among certain people”. Inspector Hider also saw copies of the ‘Camberwell Strike Bulletin’ also produced at Central Buildings on a duplicator by Eddy Jope, who denied any connection with the ‘Peckham Labour Bulletin’.

Trams were not running, till the local electricity generating station was reopened by naval ratings…

On May 5th, commercial vehicles were stopped & trashed here by strikers. The trams were in the main kept off the roads. Altogether there were 12 attempts by voluntary (mostly middle class) recruits supported by police and special constables to run trams from Camberwell Depot to New Scotland Yard – resulting in crowds of pickets and supporters attacking scab trams, smashing their windows and pushing them back inside, preventing them from running.

The British Worker (A daily paper put out during the Strike by the TUC) reported:

“BANNED TRAMS SCENE: An unsuccessful attempt was made shortly after four o’clock on Wednesday afternoon to run LCC tramcars from the Camberwell depot.

Earlier in the day two lorries with higher officials of the tramways Department and OMS recruits arrived at the Depot, where a strong force of police had been posted.

A large crowd, including tramwaymen, their wives and sympathisers, collected, and when the first car came out of the Depot gates in Camberwell Green there was a hostile demonstration.

Some arrests were made. Following this incident the cars were driven back in to the Depot to the accompaniment of loud cheers.” (British Worker, 5th May.)

Strike-breaking buses were also stoned in Camberwell on Saturday night (8th May) There were huge public meetings at Camberwell Green, as well as at Peckham Rye and at the triangle near the Eaton Arms, Peckham. During a public meeting at Camberwell Green, waves of police with drawn truncheons marched on the people, who broke and ran after repeated baton charges.

After the TUC sold the strike out, there was confusion here. Crowds of workers gathered at the Tram Depot, not knowing what to do. Each worker had to sign a form on future conditions of service, hours and wages. Some never got their jobs back at all.

At the end of the Strike Camberwell Trades Council sent £10 to the Miners from the funds collected during the Strike, continued that support as the miners fought on alone after the TUC sellout.

Camberwell Borough Guardians took a hard line during and after Strike – issued ‘Not Genuinely Seeking Work’ forms to stop strikers getting any dole payments.

Following the defeat of the Strike, the Government brought in the Trades Disputes Act, known as ‘the blacklegs Charter’, which outlawed all General or solidarity strikes and prevented many civil service workers from affiliating to Trades Councils… Camberwell Trades Council formed a Trade Union Defence Committee to oppose the Act – without a lot of success.

A plaque put up here remembering Camberwell working people’s action against scabs in the General Strike

1935 Painters’ strike

On March 15th 1935 a strike erupted over trade union membership among the Camberwell Borough Council painters. Eleven non-union painters were employed, but a week later, there being no agreement between the National Society of Painters and the Borough council, 85 painters were sacked. The dispute became official and following a motion condemning the employers from the Camberwell AUBTW, continued for nearly two months. The borough council was prevented under the 1927 Act from making union membership a condition of employment. Two members of the Camberwell NSP branch, E. Milligan and C Laws, were Chairman and Secretary of the Trades Council Industrial Section which strongly supported the strike.

The London Bus strike of 1958.

The Tram Depot later became a Bus Depot. In 1958, bus workers struck for higher wages, in a dispute that lasted nearly two months, but was eventually severely defeated. On May 24th the T&GWU, Camberwell Bus Garage branch organised a march of 250 from Camberwell Green to Peckham Rye to publicise the busmen’s plight. But the strike hadn’t 100% support in the area. A scab organisation known as the People’s League for the Defence of Freedom recruited drivers to drive buses. The scab drivers later revelled in the fact that they had scabbed and publicised an organisation they had formed known as ‘Blacklegs Incorporated’.

In 1998 this northern section of the Bus Garage was squatted for exhibitions and parties.

WALK THROUGH CAMBERWELL PASSAGE TO THE NORTH SIDE OF CAMBERWELL NEW ROAD, TURN LEFT AND STOP AT THE PURE GYM

Though the 1850s saw the end of Camberwell Fair, in many ways though working-class Camberwell recreation had become no less rowdy for being forced inside off the Green.

The New Grand Hall Cinematograph Theatre in Camberwell New Road, opened in 1912, on the north side of Camberwell New Road, between Depot entrance and Camberwell Passage; (it later became a Snooker Hall).

In 1956 there was a Teddy Girls and Boys riot at the New Grand, after they’d watched the pioneering rock ‘n’ roll film Blackboard Jungle, featuring Bill Haley & the Comets. Teddy girls in black jeans encouraged by their boy-friends swarmed across the rows to stamp seats free from their hinges. They stamped, clapped their hands, screamed and beat out the 12 bar blues by kicking seats until they splintered… The police scattered them, then restored order by escorting the Teddy boy ringleaders from the theatre.

Teds were the hoodies of the time: teenage working class kids, in an era of increasing prosperity emerging after the restrictions and poverty of the war years… They were listening to outlandish music that baffled their elders and betters, and getting together for dancing, drink and some splatterings of violence. Gang warfare was common between different ted gangs. The Elephant & Castle area was one of London’s strongest ted areas. A 2000-strong crowd of teds had fought the police outside Elephant & Castle’s Trocadero cinema shortly before this, inspiring similar battles across the country, mainly after viewings of the film. Respectable fears, moral panic and mass crackdown followed.

Teds were often scapegoated as the cause of all troubles and many paranoias of authority and conforming social hierarchies were projected onto them.

Today’s kids are similarly seen as out of control, street violence, knifings, shootings etc are widely seen as new and frightening developments: in many ways the terror and legal/political responses mirror the reaction to the teds, but similar scares have emerged repeatedly in the last 200 or so years. Usually no matter how serious developments are, they are represented as unprecedented; often in fact patterns and numbers are very similar. Not to disparage the genuine despair, fear and anger that the current crop of South London murders arouses. Fear of crime though, is always often out of kilter with the reality of crime. Returning to Camberwell Green, many kids now avoid the place, seeing it as too dangerous to hang out there; recently Peckham and Camberwell teens have been especially targeted as being out of control. Control of space and potential troublemakers’ access to it, seen in the enclosure and respectabilisation of the green in the 1850s, is reflected in the 6 month exclusion order regularly imposed on the centre of Camberwell over recent years, allowing the police to ‘escort’ anyone under 16 found in the area home whether they are up to anything dodgy or not.

WALK DOWN TO 303-309 CAMBERWELL NEW ROAD, THE TFC BUILDING (NEXT TO THE GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH)

Around 2001, the upper floor of this building housed the clandestine HQ of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), an undercover unit of the Metropolitan Police Service’s Special Branch.

Between 1968 and 2008, when the unit was disbanded, it organised the systematic infiltration of undercover police officers into campaigning and protest groups. Officers pretended to be activists to worm their way into 1000s of groups, from national organisations to small local campaigns, many using the names of dead children to set up false identities. The police spied on campaigns for justice for people killed by racists and by the police; animal rights activists, peace groups, union branches campaigning around health and safety, the anti-apartheid movement, anti-racists, environmental groups, socialists anarchists, feminists, MPs… Many of the (mostly male) officers entered into deceptive relationships with women in false names; they lived with people, fathered children and then disappeared completely when their tour of duty was done. Many acted as agent-provocateurs to get people arrested.

Over the last ten years activists have exposed many of the names and histories of these officers, but much more of what they did remains secret. After it was proved that the unit had spied on the family and campaign of Stephen Lawrence, murdered by racists in 1993, the government announced a Public inquiry into undercover policing would take place. We are still waiting for the first hearings to be held in 2020.

For more info contact:

Campaign Opposing Police Surveillance

For a local slant on one of the campaigns infiltrated by the SDS, see later on when we visit the Institute of Psychiatry…

BACK ACROSS CAMBERWELL NEW ROAD, WALK DOWN TO JUNCTION WITH DENMARK HILL, THEN UP WEST SIDE OF DENMARK HILL TO CORNER OF COLDHARBOUR LANE

Camberwell became well-known for music halls; many were in the back hall of pubs. Music Hall arose from the last of the old tavern ‘free and easies’, where people could get up and do turns, usually songs or comedy acts.

The People’s Palace of Varieties, or Lovejoys, at the Rosemary Branch, Southampton Way, was held in “a long, shabby room adjoining the tavern, furnished with chairs and tables, and illuminated with flaming gas brackets. At one end a stage with footlights screened with blue painted glass. A Chairman sat in front of the stage facing the audience. He wore the most deplorable evening dress. Another gent sat at the piano on the stage. Everybody seemed to be drinking and talking while a man in shirt sleeves was dashing about with a tray loaded with glasses of beer. Each turn was announced by the Chair. He rapped with his hammer both to attract attention and to assist applause. A tall gent sang a song about his wife, his trouble and strife.”

The Rosemary Branch was demolished in 1971. The Castle on the Camberwell Road bears the name of an earlier pub that housed the Bijou Palace of Varieties or Godfrey’s Castle Music Hall from 1875 to 1889.

The Father Redcap pub, on the north side of the Camberwell Green, originally held a music hall built in 1853. On 2nd December, 1867, the audience here could enjoy “the great W J Collins, a banjoist from America, a Shakespearean sketch, Professor Davis in the renowned rope trick, and Mr Mucus Hellmore in his great delineation of Mephistopholes”

Later it was a gay bar at least back to the 1970s till 1997, and later again the Red Star, a party venue, holding many gigs including benefits for various worthy causes. (we will return to this building later).

In 1896, the Dan Leno company opened the “Oriental Palace of Varieties”, on Denmark Hill, which was soon replaced with a new theatre, with a capacity of 1,553, in 1899, named the “Camberwell Palace”. Famous old timers who appeared here included Marie Lloyd, Harry Lauder, Nellie Wallace and Harry Tate. By 1912, the theatre was showing films as a part of the programme; it became an ABC cinema as “The Palace Cinema” in 1932. Later it reverted to a variety theatre in 1943, but closed on 28 April 1956 and was demolished. (The 1957 film The Smallest Show on Earth, the story of a family-run suburban cinema, was probably based on the Palace).

Nearby at the corner of Denmark Hill and Coldharbour Lane was the “Metropole Theatre and Opera House”, opened in 1894, which held transfers of West End shows: “The theatre had a very ornate interior with private boxes, stalls, dress circle, balcony and gallery. Ladies who came in their fashionable hats were respectfully informed that hats and bonnets were not allowed in the stalls or first two rows of the dress circle.”

No wonder Camberwell starred in a 1915 music hall song. Chalk Farm to Camberwell Green by Lionel Morrekton, about a young lady who went for a ride on the top of a bus with “a fellow, a regular swell”, on what is still the no. 68 bus route:

Chalk Farm to Camberwell Green

All on a summer’s day

Up we climbed on the motor bus

And we started right away

When we got to the end of the ride_

He asked me to go for a walk!

But I wasn’t Camberwell Green

By a very long chalk!

The replacement of live theatre and music by cinema was also reflected locally: the Empire was demolished to build an Odeon cinema in 1939; itself since closed in 1957, becoming Dickie Dirts (see below)… Besides these, on Denmark Hill, where Somerfield now stands, there was the Golden Domes, (later called the Rex and then the Essoldo); across the road, on the site of the Post Office, was the Bijou, known locally as the Bye Joe; and the Coronet, a small cinema in Wells Way.

WALK UP TO CORNER OF COLDHARBOUR LANE TO NANDOS

Where Nandos and the flats behind now stand, was the site of the Empire, later the Odeon, which became, as we said above, Dickie Dirts clothing warehouse. Closing in the late 1970s, it was squatted in August 1984 as a back-up/centre/crashpad/gigspace holding benefits, for the September 1984 Stop the City actions/defence fund. Stop the City was a series of days of action against the capitalist exploiters in the City of London, initially against firms making profits from war and arms manufacture, later expanding to oppose many other causes… 1000s of mainly young anarchist-influenced activists attacked, demonstrated against and besieged City institutions. The Dickie Dirts squat was evicted on 3rd October ’84 by cops, bailiffs and builders; the building’s owners apparently turned up in a Rolls Royce to watch! The three people found in Dickie Dirts at the time were kicked out. The police had broken in on the bailiffs’ behalf; obviously the Met were slightly aggravated by the Stop the City link.

Where Nandos and the flats behind now stand, was the site of the Empire, later the Odeon, which became, as we said above, Dickie Dirts clothing warehouse. Closing in the late 1970s, it was squatted in August 1984 as a back-up/centre/crashpad/gigspace holding benefits, for the September 1984 Stop the City actions/defence fund. Stop the City was a series of days of action against the capitalist exploiters in the City of London, initially against firms making profits from war and arms manufacture, later expanding to oppose many other causes… 1000s of mainly young anarchist-influenced activists attacked, demonstrated against and besieged City institutions. The Dickie Dirts squat was evicted on 3rd October ’84 by cops, bailiffs and builders; the building’s owners apparently turned up in a Rolls Royce to watch! The three people found in Dickie Dirts at the time were kicked out. The police had broken in on the bailiffs’ behalf; obviously the Met were slightly aggravated by the Stop the City link.

Dickie Dirts was resquatted several times, eg in June 86 for gigs, when Camberwell indie band House of Love played here.

Dickie Dirts was resquatted several times, eg in June 86 for gigs, when Camberwell indie band House of Love played here.

The Dickie Dirts building, after standing derelict for most of a decade, was demolished in Spring 1993, and a block of flats for homeless young people called ‘The Foyer’ was built on the site, plus a restaurant; this was later replaced by Nandos.

Camberwell has also played host to a number of other squatted venues and social/political spaces and centres, as we will relate…

WALK DOWN COLDHARBOUR LANE TO CORNER WITH CRAWFORD STREET, AT KING GEORGE COURT

Crawford squatted social centre, on the corner of Crawford Street and Coldharbour Lane, 2003. Run by the Black star collective (who had previously occupied another squat in the Coldharbour Lane area), the place held gigs, a “lost film festival”, and served as a drop in centre for some local old Jamaican dudes… After the collective handed out invitations to locals to come and get involved (in which they charmingly asserted that they ” are well-mannered and reasonable people…. Not into drugs or anything alike.” This building was still empty 5 years later after its eviction by Lambeth Council, though flats have now been built there.

WALK BACK DOWN COLDHARBOUR LANE TO DENMARK HILL, OVER ROAD AND BACK DOWN TO JOINERS ARMS

The old Muesli Factory behind the Joiners Arms was squatted around 1992-3… mainly for rave parties etc… By some of our remembrance, it could be a bit nasty in fact, a lot of aggro and some bad drugs.

And others: the Old Labour Club and Groove Park, which we’ll talk about later), also some others which are bit off the route of this walk:

Location, 299 Camberwell New Rd, Squat party by LSDiezel crew is advertised for 7th Feb 1992. Were other parties held? Probably. Demolished?

Area 7, 64 Camberwell Church Street: An ex-Council Building squatted for an arts centre in 1993 but quickly evicted.

Kwik Fit on Denmark Hill, was squatted for 2 (or more?) punk shows in October + December 2003.

There have been some great local squatted social centres more recently too;

Warham Street, the Black Frog/Camberwell Squatted Centre in 2007

The Library House, behind the Minet Library, squatted 2008

WALK BACK UP DENMARK HILL TO CORNER OF DANEVILLE ROAD, WALK DOWN TO ALLENDALE ROAD OR KERFIELD CRESCENT

Squatting

The modern squatters’ movement started in 1969 caused by the contrast of rising rents and widespread homelessness, while thousands of houses stood empty, many being slum clearances and Compulsory Purchase Orders, that local councils had left to rot for years (up to 7 years in some cases). The 1970s saw a huge increase in squatting, both for personal housing needs and increasingly as part of an alternative lifestyle that questioned, opposed or rejected traditional conformist ways of life, including work, the sanctity of private property (including leaving houses empty), and conventional social, sexual and economic values.

Southwark Family Squatters Association had originated in October 1970 when Lewisham squatters occupied some empty houses in Peckham. At this time councils had, under pressure from squatters and lengthening waiting lists, started to licence squats in property they were planning going to use, notably in Lewisham.

Squatting in Camberwell began in January 1971 in Cuthill Road, Allendale Road and Kerfield Crescent (all just to south of Daneville Road) in houses left empty, while the Daneville Road/Selborne Road area was waiting for redevelopment, scheduled in 1974. Southwark Family Squatters Association moved 4 homeless families in to nos 13 and 25 Cuthill Road, 44 Allendale, and 22 Kerfield Crescent. The Council claimed they were going to repair the houses and use them, but squatters, and others, had their doubts. The families had all been made homeless due to private eviction or were living in properties too small or unhealthy, and had been let down by the council refusing to rehouse them or dragging its feet.

The following report appeared in Camberwell Candles, in February 1971:

“You might be forgiven for not noticing anything very special about these houses. They look ordinary outside And inside, the only noticeable things are the good state of the decoration and the absence of any of those damp patches that afflict many older properties in Camberwell.

But since January, when the Southwark Family Squatting Association moved in

and rehoused four families under eviction orders from their previous homes, 4 of these houses have been the homes of squatters .

Before the squatters moved in these houses were empty with doors and windows boarded up – usually a sign that nothing’s going to happen for a long time.

The Council say that the Houses were awaiting “patch repairs” – which you might find curious if you were to go and inspect them. The only repairs needed that anyone other than the Council can see – are an outside wall that needs some attention, and a roof that leaks slightly into a landing – just enough with

The Council say that the Houses were awaiting “patch repairs” – which you might find curious if you were to go and inspect them. The only repairs needed that anyone other than the Council can see – are an outside wall that needs some attention, and a roof that leaks slightly into a landing – just enough with

an hour’s rain, as one of the squatters’ children put it, “to make a baby’s puddle” …. hardly enough to warrant boarding the place up when there is a housing waiting list of thousands, many of whom are desperate for a decent home.

Squatting sadness

The story of Southwark’s squatters is a sad one. NOT just because the squatters’ hopes for decent homes are being frustrated the Borough Council sticking to the rules of bureaucracy – though that may

true.

NOT just because some families in really desperate need are being kept waiting because houses intended for them have been taken instead by squatters – though that may be true.

BUT BECAUSE the Council and the squatting associations are in conflict and are

frustrating each other’s activities IN SPITE OF THE FACT that their aims are basically the same – to improve the housing situation in Southwark.

THE REASON for this is simply that the two sides are not cooperating with each

other.

THE BLAME for this non-cooperation non-cooperation is the Council’s. The Southwark Family Squatting Association wants to cooperate: the Council does not

SQUATTING IN CAMBERWELL

Camberwell’s first squatters are in Cuthill Road, Allendale Road and Kerfield Crescent. Before the squatters moved in, the 4 houses were boarded up and there was no way of finding out exactly what was going to happen to them. The whole area, including Dane ville Road & Selborne Road,is due for redevelopment in 1974. It seems un likely that houses should be kept empty for that long – but it has been known to happen before.

THE BOROUGH COUNCIL

The Press Officer at the Town Hall when asked why these houses had been boarded up, said he had no details of particular properties, but that most such houses were in development areas due for demolition. Southwark now has about 1600 empty houses, 1200 of them due for demolition this year, and the other 400 due for repairs.

The Asst. Town Clerk, Mr Thomas, said that the four houses in question aimed at putting people into property were in fact due for “patch repairs. And he complained that the squatters, by taking over the houses before the repairs were done, had deprived other families at the top of the waiting list of their rightful tenancies.

When asked what repairs needed to be done, Mr Thomas said that he could not give details – not that there was any secret about it, but because with hundreds of repair jobs either on the files awaiting approval or in the hands of various sub-contractors this would be difficult.

Why did the Council not get the repairs done before the squatters moved in? Because, apparently, there is always “considerable delay what with decisions and the sub-contractors’ – with architects’ plans and committees decisions and sub-contractors’ own schedules.

THE SQUATTING ASSOCIATION

When given Mr Thomas’ information that the houses had been due for repairs, Mr Barry Stone, of the Southwark Family Squatting Association said that if only the Association had known that in advance, they would not have taken them over: “WE are only too pleased if the Council are going to USE a house.

If they would only tell us which empty houses they do not intend to use and which are awaiting repairs, we will vacate the ones they want to use. Our programme is aimed at property that is not going to be used again.

But the Council refuse to give us any information”.

The squatters have also told the Council that if the Council would co-operate, they would give an undertaking only to house people on the Council’s housing list, and in consultation with an officer from the Council.

THE SQUATTERS OWN STORIES:

Aston and Zoila Bartley are now at 13 Cuthill Road, having squatted previously at Gordon Road Peckham, where they had an eviction order. Prior to that they were in Bermondsey, but the flat was damp and unhealthy and in their opinion “No place for the kids!!

They have 3 children, the youngest a baby of a few weeks born by Caesarean.

In Bermondsey Mrs Bartley had pneumonia and a lot of bronchitis – due

to some extent at least to the damp.

Joseph and Joan Peters are at 44 Allendale Road. They too have squatted before, and been evicted, having left a fiat in Lausanne Road that they found far too small for the whole family.

The Peters have had trouble even getting on the housing list at all,

apparently through letters to and from the Council going astray somewhere along the line. This has been more than usually frustrating, since one of their children is “in care” and not allowed home until “suitable accommodation” is found. But they are hopeful of hearing good news from the Council before too long.

Gloria McFarlane of 25 Cuthill Road lives there with her husband Lloyd and their 4 children. They too were evicted from Gordon Road, having already been evicted from a flat in Bermondsey when their landlord wanted the flat for his own family.

The McFarlanes were offered accommodation in Barry Lodge in Sydenham.

They refused it – “It was so filthy!”

John & Beryl Lindsay… 22 Kerfield Crescent. They had a flat in Southwark from which the

landlord evicted them in September.

The Council refused to offer them a place at all – for the unfortunate reason that, although they have been together as man and wife for 8 years they are not officially married, and are therefore classed as an engaged couple!

Since they moved into Kerfield Crescent, they have been offered a place in Chaucer House. “But the state of the place was so bad”, said Mrs Lindsay, “that I wouldn’t take

children in there. A friend of mine was sent there – just for 6 months

they told her – she’s been there four years!”

(Report from Camberwell Candles magazine, St Giles Camberwell Church, Feb 1971)

The were some 1600 empty street properties in the Borough of Southwark at the time. Southwark Council refused to do deals with squatters as other councils had – the local authority was old-Labour controlled, John O’ Grady (later infamously to join the gentrifying redevelopers of the London Docklands Development Corporation) was in charge, and their approach to housing and local politics in general was “we do stuff FOR people, they don’t do it for themselves.” They evicted the Camberwell squatters and trashed the houses to stop them being occupied, claiming the houses could be patch repaired & used for people in the normal way, and that squatters were “queue jumping”.

In response the squatters launched a campaign for the Council to recognise the  squatters, and give them licences… their tactics included marches, demos, and deputations to the Town Hall. On 21 April 1971 FSA families invaded the Town Hall Council Chamber, 50 people barricaded themselves in and held an alternative council meeting. When Council Leader John O’ Grady tried to speak the squatters’ Mayor ruled him out of order!

squatters, and give them licences… their tactics included marches, demos, and deputations to the Town Hall. On 21 April 1971 FSA families invaded the Town Hall Council Chamber, 50 people barricaded themselves in and held an alternative council meeting. When Council Leader John O’ Grady tried to speak the squatters’ Mayor ruled him out of order!

They also occupied Transport House (the Walworth Labour Party HQ) on 10 May 1971, 30 people were involved, waving a banner reading: ‘Labour Southwark fights the Homeless’.

The Council still refused to deal with the squatters, and pressed on in court, but good legal defences meant cases got adjourned in many cases… Some Council social workers were in fact supporting the squatters, despite pressure from above. Southwark applied for injunctions to stop named squatters entering council property (a tactic revived by Southwark against squatters in the Heygate Estate in Elephant & Castle in 2006) – but in fact made a mess of this.

We’ll continue this story round the corner in Grove Lane…

BACK TO DENMARK HILL, TURN LEFT, WALK UP HILL TO FRONT OF MAUDSLEY HOSPITAL

Camberwell’s association with mental health care/imprisonment goes back centuries: there were two large ‘lunatic asylums’ on Peckham Road in the 18th-19th centuries… (Which we’ll come to later)

The Maudsley

The Maudsley Hospital dates from 1907, when Dr Henry Maudsley offered London County Council £30,000 (subsequently increased to £40,000) to help found a new mental hospital that would:

– be exclusively for early and acute cases,

– have an out-patients’ clinic,

– provide for teaching and research.

The Hospital was always intended to be a progressive centre of treatment and research rather than confinement and “asylum”. World War I intervened and the Hospital didn’t open until 1923. A specific Act of Parliament had to be obtained (1915) to allow the institution to accept voluntary patients.

The Maudsley continues to provide in-patient and community mental health care to local people in Southwark and Lambeth and nationally across the UK, though contested, and problematic, (see below) In close proximity to the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College London it is also a contributor to both psychiatric research and the training of nursing, medical and psychology staff in psychiatry.

As part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust (SLaM) it also has close links with Bethlem Royal Hospital – the original “Bedlam”.

Reclaim Bedlam, and Mad Pride

“In 1997, the Bethlem and Maudsley NHS Trust marked the Bethlem hospital’s 750th anniversary with a series of celebrations. Pete, who had been a patient at the Maudsley, saw nothing to celebrate in either the original Bedlam (“a symbol for man’s inhumanity to man, for callousness and cruelty,” in historian Roy Porter’s words), or the state of mental health care.

“How can you celebrate LOBOTOMY, LIFETIME INSTITUTIONALISATION – TAKING YOUR OWN LIFE – DEPRESSION – DRUG DEPENDENCY ECTS…” (Survivors Speak Out)

1997 saw the 750th anniversary of ‘Bedlam’ – the asylum which was the precursor of the Maudsley. Inside the Maudsley were anniversary “celebrations”, outside was a big demo of mental health survivors under the banner of “reclaim bedlam”, organised by Pete Shaughnessy.

Reclaim Bedlam organised ‘Raving in the park”, a picnic/rave/a sit-in outside the original Bedlam site at the Imperial War Museum to protest.

“Maudsley & Bethlem Mental Health Trust saw itself as la crème de la crème of mental health. In 1997, it was more like the Manchester City of mental health. Situated in one of the poorest areas of the country, it put a lot of resources into its national projects, and neglected its local ones.

It’s history went back to the first Bedlam, the first institution of mental_health. If you pop down to the museum at Bethlem Hospital, you will see a picture proudly displayed of the 700th celebrations in 1947, with the Queen Mother planting a tree. Well, not exactly planting, more like putting her foot on a spade.

So, when some PR bureaucrat came up with the idea of 750th_celebrations, it must have all made sense. An excuse for a year of corporate beanos. The Chief Executive could picture the MBE in the cabinet. There was only one problem: in 1947, the patients would have been well pleased with a party, in 1997 some patients wanted more.

In the so-called ‘user friendly’ 90s, I thought ‘commemoration’ was more appropriate. So, a few of us went to battle with the Maudsley PR machine. It was commemoration vs. celebration.

I think for the first time, we were taking the user movement out of the ghetto of smoky hospital rooms and into the mainstream. We spoke at Reclaim the Streets and political events. We would gatecrash conferences to push the message. I know we pissed users off by our_style; personally I found some users more judgemental than the staff we talked to. They were even a few users who wanted to have their stall at the ‘Funday’ and cross our picket line. Frustrating. When that proposal was put to me, I lost my nut, which meant I threatened to_bring Reclaim the Streets down to smash up their stall. Because of that remark, I had two police stations hassling me up to the day_of our Reclaim Bedlam picnic and the picket at the staff ball, the_appropriate opening event of the celebrations, had to be dropped.

We had our first picnic at Imperial War Museum, one of the sites of Bedlam Hospital; Simon Hughes MP came and spoke. Features in Big Issue and Nursing Times, and we were afloat.