In June 1595, 1,000s of apprentices took part in a series of riots on Tower Hill in London, culminating in an abortive plan for insurrection. The rioters were mostly very poor, protesting about the appalling social conditions of 1590s London. Their grievances included the scarcity and rising cost of food, the greed of the mayor and of other wealthy citizens. But as the month went on, the repression of the protests and mistreatment of participants became a grievance that escalated the movement…

The 1590s were a decade of social and political crisis. Food prices rocketed, partly due to scarcity; four successive harvests failed between 1594 and 1597. Inflation led to high prices; wages fell up to 22 percent from the previous decade, and real wages are thought to have been at their lowest for centuries before or after.

Taxes were heavy, and many of the poor struggled to pay them (in 1593, people were said be ‘selling their pots and pans to pay tax’) there was constant threat of invasion from Spain and war in Ireland… Acute hunger in the countryside led large numbers of rural dwellers to flock into London in the hope of finding work or at least relief; but employment in the capital plummeted. The economy was stagnating.

In London, the pressure of food shortages and high prices for staple foodstuffs led to discontent, and to protests. Flour prices in the capital increased by 190 percent between 1593 and 1597, other food underwent similar increases.

In June 1595, the crisis provoked food riots in the City of London, the first since the 1520s. There were 12 riots or large scale crowd protests between 6th and 29th June, in London and Southwark. Seditious libels were circulated attacking the authority of the Lord mayor, Sir John Spencer, know as ‘Rich’ Spencer, for his great wealth.

In the first riot of June 6, apprentices numbering two to three hundred rescued a silkweaver who had been committed to Bedlam after protesting outside the Lord Mayor’s house.

On 12th June, there was a riot over the price of fish: This appears to have been sparked when apprentices sent to buy fish at Billingsgate market found all the fish had been bought up already by ‘fishwives’ (market stall holders in effect). The apprentices seized the fish and sold it at the rate already agreed by the mayor. (The implication being the fishwives were preparing to sell the fish at a dearer price).

On 13 June, a riot over price of butter took place in Southwark, the part of the City south of the river Thames, and known for lawlessness and rebellion. 300 apprentices assembled in Southwark, took over the market and enforced the sale of butter at 3d. per pound where the sellers had been charging 5d. They also issued a proclamation that butter be bought and sold openly in the markets not old to private houses or inns.

In both these cases it is stressed in contemporary accounts the discipline of the crowds concerned, and that their actions were agreed to or at least accepted by magistrates. The riots have been suggested as examples of the ‘moral economy’ described by some historians, identifying a common vision of accepted prices, practices and relationships, which to some extent united some people from all classes in the pre-capitalist era. Inflating prices was viewed as immoral, breaking agreed levels of subsistence, especially on food staples, and collective action, even if it broke the law, was widely condoned, even among some in authority. A part of this was the aim of maintaining social peace, but there was also an element of upper class paternalism, an ideal of vertical social relations, but characterised by the responsibility of those in power to treat the lower orders benevolently to some extent. This was increasingly being threatened by evolving interests out to increase profits.

On 15th June, crowds attempted to rescue jailed comrades: “At this day certain prentices being committed to the Counter [the city Prison] by the constable for some misdemeanours, divers other prentices congregated themselves and came to the Counter and said they would have them forth again, using very hard speeches against the Lord Mayor; but the gates being shut against them and they not prevailing, they tarried not long but departed away.

The same day, not long after the said assembly of prentices at the Counter, a serving man that had a prentice to his brother dwelling in Cheapside, which prentice had complained of his master’s hard usage towards him to his said brother, the serving man hereupon coming to the master and quarrelling with him about the misuse of his brother, in multiplying of words the serving man brake the master’s head; and by this brawl the people gathering together and much hurley burley following, Sir Richard Martin hearing thereof came forth into the street, apprehended the serving man, and by the constable sent him to the Counter. As he was in carrying thither the prentices that formerly had resorted to the Counter and would have taken thence the prentices as aforesaid, did meet with this serving man, rescued him from the constable, and brought him back to Cheapside. Whereupon Sir Richard Martin, hearing of this disorder, came forth suddenly with such company as he had of his own servants and presently apprehended the serving man again, reprehended the prentices for their so great disorder, took six of the principal offenders, and so by the constable sent the serving man and the six prentices to the Counter, and caused irons to be laid upon them all. About an hour after when all things were quiet, saving only some dregs of people remaining in the streets gazing and expecting for novelties, as in such matters always it happeneth, the Lord Mayor, hearing of the broil and business which Sir Richard Martin had appeased and not knowing thereof, comes into Cheapside, accompanied with Sir John Hart, where finding all things in quiet, Sir John Hart, accompanied with Sir Richard Martin, went again to the Counter, charging the keeper thereof to look well to his prisoners and to see irons laid upon them all and to be safely kept, and so they returned to their houses.

The Lord Mayor likewise, after he had sent Sir Richard Martin and Sir John Hart to take order for the safe keeping of the prentices in the Counter, also presently returned towards his house, and about London Wall a prentice meeting him would not put off his cap unto him, whereupon the Lord Mayor sent him also by his officers to the Counter, which was done quietly and without opposition of any.”

Clearly, the troubles were beginning to move beyond moral economy and into dangerous subversion. And the spirit of unrest was being spread to the army – always a dodgy moment for the powers that be:

About the 16 or 17 of June, “certain prentices and certain soldiers or masterless men met together in “Powles”, [St Pauls] and there had conference, wherein the soldiers said to the prentices, “You know not your own strength”; and then the prentices asked the soldiers if they would assist them, and the soldiers answered that they would within an hour after be ready to aid them and be their leaders, and that they would play an Irish trick with the Lord Mayor, who should not have his head upon his shoulders within one hour after. At which time they spake of farther meeting together.”

The tensions did not die down yet.

On the 27 of June, “certaine young men apprentices and other, were punished by whipping, setting on the Pillory, &c. for taking 500 pounds of butter from the market women in Southwarke after the rate of 3 pence the pound, whereas the sellers price was 5. pence the pound. [the shepherds] caught the bakers up and took from them about four or five dozen cakes, for which they paid them the usual price, however, giving them a hundred walnuts and three baskets of grapes.”

The public whipping and pillorying of some of these rioters instigated a further riot that day – the pillories were torn down, and a gallows was erected in front of the house of the Lord mayor.

On the evening of 29 June, a crowd of at least 1000 apprentices marched on Tower Hill. According to reports they planned to ransack gunmakers shops and then rob the rich and take over the City: ‘to robbe, steale, pill and spoil the welthy and well disposed inhabitaunts of the saide cytye, and to take the sworde of aucthorytye from the magistrats and governours lawfully authorised’.

The crowd was said to have included shoemakers, girdlers, silk-weavers, husbandmen, apprentices, discharged soldiers and vagrants; they carried “halberds, bills, goones, daggs, manie pikes, pollaxes, swords, daggers, staves and such lyke.”

When City officers, the Watch from Tower Street ward, arrived to try to pacify or disperse them, the crowd stoned them, displaying a banner, “hartened unto by the sounding of a Trumpet… the Trumpeter having been a souldier.” Others tore down the pillories in Cheapside, the City’s main drag,

Even more seriously for the City authorities, it seems that the rioters won some support from the Lieutenant of the Tower, Sir Michael Blount and his garrison. When the Mayor arrived with sheriffs to make arrests and read a proclamation ordering the rioters to disperse, Blount objected to the carrying of the Mayor’s sword of justice before him, and about 10 of his garrison not only refused to help repress the crowd, but weighed in against the sheriffs, and “assaulted an beat the sword-bearer and the mayor’s servants.”

The riot on Tower Hill was the largest uprising in the City of London in nearly 80 years, and was unusual in its direct criticism of the elite.

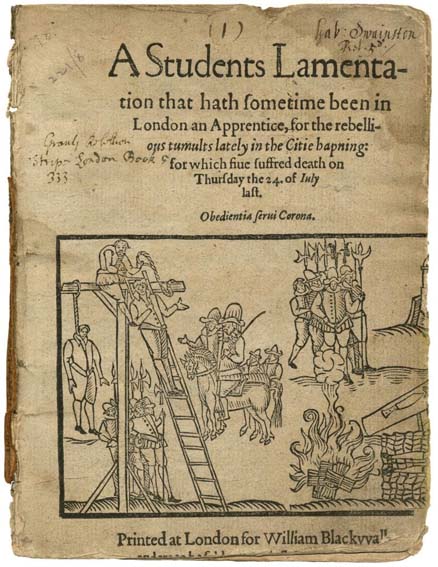

The Lord mayor of London was so worried about the protests and especially the plot of 29th June, that he appealed to queen Elizabeth. In response she issued a royal proclamation “for apprehending such vagrants and rioters. In which her majesty signified her will to have a provost-marshal with sufficient authority to apprehend all such as should not be readily reformed and corrected by the ordinary officers of justice, and them without delay to execute them upon the gallows by order of martial law. And accordingly Sir Thomas Wilford was appointed provost-marshal, who patrolled the city with a numerous attendance on horseback, armed with pistols, apprehended many of the rioters, carried them before the justices appointed for their examination, and after condemnation, executed five of them on Tower-hill.”

Five apprentices appear to have been hanged on Tower Hill on July 24th.

In his order of execution, the Mayor directed each inhabitant of the ward “that they keepe within their houses all their men servants and apprentices to morrow from three of the clock in the morning untill eight at night, and the same householders be . . . all that time ready at their door . . . with a weapon in their hande.”

The mayor also requested that the Privy Council suppress stage plays, which they claimed had incited “the late stirr & mutinous attempt of the fiew apprentices and other servants… the casue of the increase of crime within the City.”

Some of the price-enforcing apprentices, though initially punished for the misdemeanors of riot and sedition, were retroactively charged in 1597 with treason, following the reasoning that the popular attempt to regulate prices constituted an attempt to alter the laws of the realm by force.

The hunger thousands were experiencing didn’t end in 1595, and nor did attempts to remedy the situation by force. In 1596, there was an abortive attempt to launch an uprising in Oxfordshire at Enslow Hill, which seems to have arisen from anger at enclosures locally, but inspired by the food riots in London and elsewhere. The plotters had aimed to link up with the London apprentices, who were clearly seen as up for continuing the fight. However, the plotters, who had allegedly intended to murder local enclosing landowners, attracted too little support, dispersed when it was obvious there were not enough of them, and were easily rounded up when one of them stupidly confessed to his employer.

The council from its treatment of the rebels considered the Enslow rebellion threatening although in reality it never got started. Five ringleaders were taken to London, interrogated, imprisoned for six months, tortured and then sentenced to death for making war against the Queen. In June 1596 two were hanged, drawn and quartered the fate of the rest is unknown.

The rioting of the 1590s did die down, possibly in the face of the threat of massive repression. But although the bad harvests, the constant war and heavy taxation had produced a time of crisis, as England entered the 17th century, increasing enclosures and dislocation were to continue to pile pressure on the poor, and economic and social transformation would produce uprising and resistance on a scale that would dwarf the events of 1595…

Sources: (A New and Accurate History and Survey of London, Westminster, Southwark, and Places Adjacent… Edward and Charles Dilly 1766)

The Pursuit of Stability: Social Relations in Elizabethan London, Ian W. Archer

The London Apprentice Riots of the 1590s and the Fiction of Thomas Deloney, Mihoko Suzuki

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2018 London Rebel History Calendar

Leave a comment