In the 18th century, it could be dangerous to nip down the pub near the River Thames… Or pretty much anywhere in the country… and not just because the drinks were a wee bit stronger than today.

You also ran the risk of being accosted and politely asked if you would like to serve your country in an aquatic capacity… Since medieval times it had been the royal prerogative to impress free men into the navy, usually violently grabbing those too drunk to resist, since most men weren’t keen to sign up for an unknown length of time on a leaking ship eating rotting food, lousy with pests and disease and THEN get killed fighting the poxy pointless wars of their ‘betters’; with a fair chance that if you survived, they wouldn’t pay you for several years. “They were taken in any way, usually at night, through violence, entrapment, and fraud. Before anyone could discover their absence, they were taken on board and locked up until the ship sailed from port. The captured men were often wounded and would die from lack of treatment.”

This custom of using pressgangs to ‘recruit’ was roundly condemned – except when the nation was at more, when the “necessity of the sudden coming in of strange enemies into the kingdom” (read: the need to bash the fuck out of some foreigners, preferably – though not exclusively – defenceless ones with some natural resources worth snaffling) justified any mean necessary. “Outrages were of course deplored; but the navy was the pride of England, and every one agreed that it must be recruited.”

Some suggested other methods for guaranteeing the navy didn’t lack numbers, barmy ideas like paying higher wages, limiting the years of service, and increased pensions. Fucking liberal do-gooders.

During times of war, pressgangs would roam towns and the countryside to take men against their will to serve in His Majesty’s navy. Sailors were most at risk, as they were obviously more useful naval fodder. In theory, impressment was restricted by law to seamen. They were kidnapped on the coast, or seized on board merchantships, like criminals: ships at sea were raided for their crews, and left without sufficient hands to take them safely into port. But since the gangs operated on a bounty per head, and would be backed by authority in any dispute, in reality anyone not rich was fair game.

In vain did apprentices and landsmen claim exemption. They were accused of being “skulking sailors in disguise, or would make good seamen at the first scent of salt-water; and were carried off to the sea ports. Press-gangs were the terror of citizens and apprentices in London, of labourers in villages, and of artisans in the remotest inland towns. Their approach was dreaded like the invasion of a foreign enemy. Soldiers were employed to assist the pressgangs: villages invaded, sentries standing with fixed bayonets; and churches surrounded, during the service, to seize seamen for the fleet.”

The pressgangs’ best defence against bad publicity was to target those they knew would find little support among the establishment or the literati –

“rogues and vagabonds, who were held to be better employed in defence of their country, than in plunder and mendicancy. During the American war, impressment was permitted in the case of all idle and disorderly persons, not following any lawful trade or having some substance sufficient for their maintenance. Such men were seized upon, without compunction, and hurried to the war.”

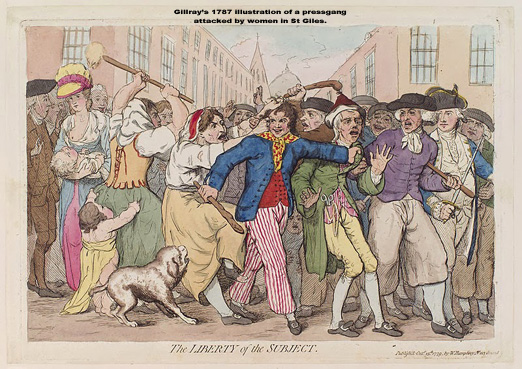

Men’s only resort was to leg it – or to fight back. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries teem with stories of resistance to the press gang. Rumour of the pressgang’s being on the prowl could lead quickly to a crowd gathering to resist them, or to attempt rescue of anyone already grabbed. These affrays were often bloodily violent – “threatened seamen were prepared to use knives, cutlasses, pokers, shovels and broken glass to defend themselves.” Ears, noses and eyes were often lost; a quarter of all battles with pressgangs between 1740 and 1805 involved serious injuries or fatalities.

A popular target for the gangs were London’s rookeries and slums – however, the basic solidarity of the poorest, often causal workers, beggars or crims, could backfire on them. For instance, one such attack on The Mint, Southwark’s most notorious rookery, in 1721, ended with the pressgang being heavily beaten.

The Seven Years war, 1756-63, which involved much of Europe, saw bitter fighting between England and France in Europe and the Americas. Death rates were high, and demand for bodies to replenish the naval losses was constant. The press gangs were working flat out.

Attempts were made to control their activities. In 1758, a bill passed the House of Commons that would have extended habeas corpus (a writ requiring a person be brought before a judge or court especially for an investigation of a restraint of the person’s liberty; used as a protection against illegal imprisonment) to pressed men. Although this act was designed to stop impressment into the army it would have seriously sabotaged the war effort: pressure was brought to bear and the bill failed in the House of Lords

During one night of savage ‘recruitment’ on the river Thames, when hundreds of men were pressed, the crew of one ship, the Prince of Wales, armed themselves and prepared to resist.

The 22nd of June 1758 is described as “a hot press for seamen, when upwards of 1400 men were taken in the river for his majesty’s service” in the London Magazine… “the hottest since the war began… no regard being had to protections… The crew of the Prince of Wales, a letter of marque ship, stood to arms, and saved themselves by their resolution.” (Annual Register, 1758).

We know little more – whether or not there was a fight, or whether their show of force was enough. However, we know they successfully avoided impressment.

The ship was described as ‘a letter or marque ship’ – basically a licensed pirate, a privateer, usually issued a licence to attack and capture enemy vessels and bring them before admiralty courts for condemnation and sale. Cruising for prizes with a letter of marque was considered an honourable calling combining patriotism and profit, in contrast to unlicensed piracy, which was universally reviled’.

Possibly the ship’s profession made the crew were a bit too tasty for the pressgang’s liking…

The Press Gang: Naval Impressment and its opponents in Georgian Britain, by Nicholas Rogers, and The Press-Gang: Afloat and Ashore, J. R.. Hutchinson, are worth a read…

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the 2016 London Rebel History Calendar – check it out online

Leave a comment